Affirm: The Morality of Money

Affirm in 1 minute

PayPal co-founder Max Levchin is back. Affirm, the “buy now, pay later” solution led by Levchin is slated to list on the Nasdaq before the year is out. The wisdom of the company’s mooted $10 billion valuation may depend on the perspective of the investor in question. Is Affirm a lender, selling a commoditized product? Or is it a payments network, capitalizing on changing consumer preferences to steal share from big banks? For Levchin, Affirm’s disruption of traditional finance is not just a commercial opportunity but a moral imperative.

Affirm’s revenue for the financial year ending June 2020 stood at $509.5 million, a 93% improvement from the year prior. Such growth requires contextualization, though — 28% came from a single merchant partner: Peloton. Like many other public debutants this year, Affirm has yet to post a profit, with net losses of $120.5 million in 2019 and $112.6 million in 2020.

Founders Fund, Khosla Ventures, Lightspeed Venture Partners, and Jasmine Ventures represent major contributors to Affirm’s $1.5 billion in financing, and are set for a major windfall.

Analysts

Introduction

The man swung the Geiger counter down the boy's leg. Again, it beeped, ominously quickly. He held the wand in his hand, looking at the thin figure in front of him. Then, he turned to the boy's mother.

"It's in his leg...we maybe have to cut it."

Forty-eight hours earlier, 90 miles north of Kyiv, a power plant had caught fire or exploded. No one was sure, exactly, what had happened, though Elvina Zeltsman had an idea. A physicist by training, Elvina spent her days at the Institute of Food Science's radiology lab. Each morning, she would load produce and foodstuffs into a lead-lined container and observe its readouts.

How contaminated were the eggs? What had polluted the eggs?

Elvina registered the results in a computer, a hefty, cabinet-like thing. Sometimes her son would help her. Maksymilian. He had a mind for it and an obsessiveness that would follow them home. When he didn't have a computer to work with, he'd write "programs" on sheets of paper.

On that morning in late April, shortly after the accident at the Chernobyl Nuclear facility — whatever it was, the government wouldn't say — Elvina looked at the loaf of bread. It had come from the north, not far from the power plant. It was glowing.

Suddenly, Elvina understood what had happened. It didn't take long for her to act. Within hours she'd jumped onto a train with her children, heading to Crimea, 1,000 miles away. As they traveled, news spread, so much so that by the time they disembarked near the Black Sea, they were greeted by police, equipped with Geiger counters.

The man in the uniform scanned Elvina, then Sergey, just a toddler. And finally, he came to Maksymilian. To Max. No matter what resolution he set it to, the Geiger kept beeping. There was no other solution beyond amputation.

But before the man could take Max, ferrying him to a hospital for his procedure, Elvina had an idea.

"Try it again with his shoes off."

The Geiger counter passed over Max Levchin, in socks, about to lose his leg — and did not beep. As it turned out, a rose thorn soaked with acid rain had lodged in the sole of the shoe, causing the elevated reading.

Remembering it years later, Levchin would describe it as an unusually lambent moment.

I have never seen that shoe again. I have flashes of memory from that time. Once you're hitting 40 which is roughly where I'm at now almost, a lot of your memories begin to crystallize into things that almost feel untrue but are so much brighter.

In some respects, it also seemed to serve as a dividing line in the computer-obsessed boy's life. Shortly afterward, he and his family emigrated from a tattered Soviet Union, arriving in the United States with $733 to their names. On the flight over, Levchin recalled asking his mother if they could spend $650 of it on a computer, to which she responded, "You're totally crazy, aren't you?"

Affirm's S-1 harkens back to the American era in which Levchin arrived. The reference isn't made explicitly, of course, but nevertheless shades the argument of filing. The 1980s, at least within certain circles, came to be defined by the gleefully carnivorous mantra: Greed is good. Affirm says something different but related: it is ok to want; it is good to buy; there is a right and wrong way.

Three times in his opening letter, Levchin emphasizes the "moral" improvement Affirm provides over traditional banking.

[O]ne could argue cards have devolved, even become corrected. The barely-readable fine print makes only one thing clear to consumers: you'll never know exactly what your purchase will really cost you...We believe that the morality of each financial product offered to our consumers is a key consideration, and is an essential part of the Affirm brand.

Later, he adds:

Our core strengths and competitive advantages remain in two fundamental areas: we are very good at technology and we are committed to being good.

Just as it would be too much to expect a payment provider to condemn consumerism, so too is it surprising to see the company frame it as a battle between good and evil, a matter of principle.

The subtext is clear: the problem is not our desire to buy, but the tools we are given.

In its embrace of spending, the framing of its mission as enabling "consumers' long-term prosperity," Affirm's S-1 filing feels fundamentally American. Less the chaotic, distended America of today, more the fiscally unconflicted America of the 1980s, the America that greeted a young Levchin. That country may never have existed in truth — no decade fits quite that neatly within a Hollywood phrase. But beyond the fundamentals of the business, Affirm's long-term success may depend on its ability to further cement that ethos, stoke our desires, narrow the distance between impulse and purchase. It is good to buy beyond our means, to acquire the computer we cannot afford. And when we do, we should feel good about it, since by doing so, we have rebelled somehow, thumbed our noses and faceless banks and predatory lenders.

For Affirm and Levchin, money has its own morality.

Number of mentions in S-1

Max Levchin: 131

Cross River Bank: 77

Shopify: 44

Lending: 39

E-commerce: 35

Transparent or transparency: 33

Keith Rabois: 22

Peloton: 20

Credit card: 15

Buy now pay later: 10

Affirm history

To tell the story of Affirm, we must keep our focus on Levchin, though we can afford to jump forward.

A co-founder and CTO of PayPal during the early days of e-commerce, Levchin built his career at the intersection of fraud, underwriting, and online consumer behavior. So ingrained was he in this world that he became famous for keeping a sleeping bag at the office, perhaps as he was building out the company's risk product. Though he eventually left PayPal for a brief stint in social media, founding Slide, he soon returned to his payments roots. Affirm was founded in 2012, spun out of startup studio HVF which stood for "Hard Valuable Fun." Nathan Gettings, Jeffrey Kaditz, and Alex Rampell joined Levchin in starting the business.

Affirm launched the next year through a partnership with 1-800-Flowers. Meant to be an alternative to a credit card, it also allowed consumers to expand their purchasing power without accumulating more debt than planned. Affirm sought to bring clarity to e-commerce purchases, explaining upfront how much the consumer would end up paying and when Affirm expected them to do so. In that respect, it was simpler than using a credit card, which required an understanding of the fine print and the parsing of bundled fees. And unlike other lending products, Levchin wouldn't come and repossess your Peloton bike if you stopped paying (though he can report you to the credit bureaus).

This was the high-level sell for Affirm and others in the "buy now, pay later" (BNPL) space: consumers (especially younger generations) want more transparency, are afraid of credit cards, and don't want to take on large amounts of debt. Buying a $1,000 mattress on a credit card, hoping to pay it off before having to pay interest (and trying to calculate that interest in your head) or a late fee, sounds terrible to these consumers.

In addition to the comparative parsimony of Affirm's model, younger customers valued the instant-gratification the platform enabled; the millennial's version of layaway. The order of operations is reversed in this rendition, though: instead of paying off the debt and then getting the product, Affirms gives you the product and then asks you to pay.

Though initially slow to take-off in the US, BNPL in general, and Affirm in particular, gained steam in recent years, bringing partners like Peloton, Casper, Expedia, and Shopify into the fold. That success invited competitors with Square, JPMorgan Chase, Klarna, AfterPay, and Levchin's alma mater PayPal offering installment lending today. Fighting off those giants may scare off some investors, but Affirm will point to the market's size, the room for multiple winners, and the new product opportunities.

As early as 2015, Levchin was dreaming big.

"We are building a new bank, hopefully the largest bank in the world, by using technology from the ground up. Today, we help them buy mattresses and sets of dishes; tomorrow, a used car, maybe a new car, then a house."

The IPO is the next step in the journey for a company that wants to help you buy a new home and open a savings account after starting as a way for you to buy flowers.

Market

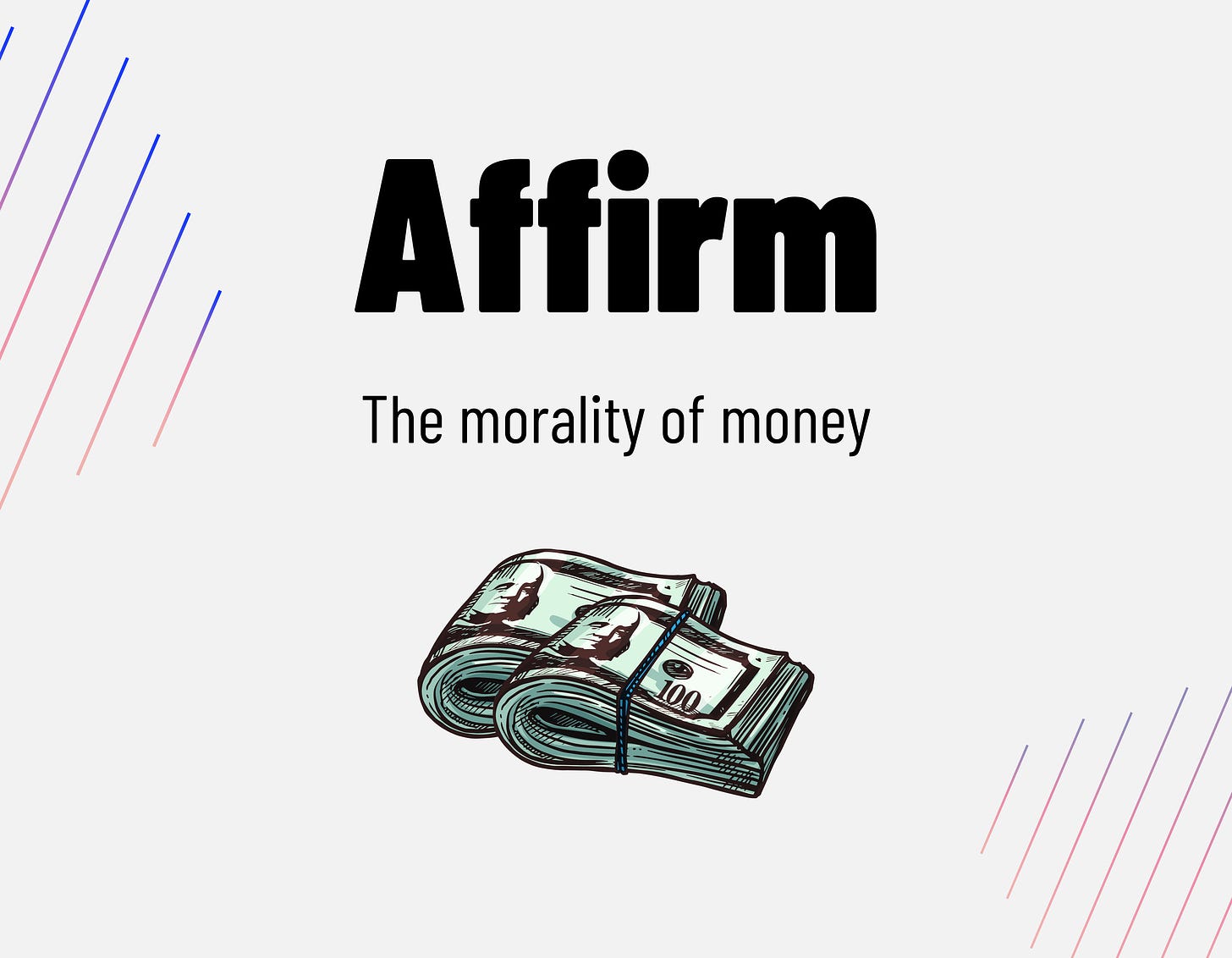

Today, the BNPL space represents a small portion of total retail spend, is concentrated in specific categories, and mostly used online. That leaves lots of room to grow.

In the US, Affirm's core market, retail sales totaled $6.2 trillion in 2019. That figure dropped to $4.5 billion when excluding auto and gas sales and grew ~4% over 2018. BNPL has seen strong adoption in categories like apparel, beauty, furniture, and electronics, which account for over $500 billion of retail sales. As of 3Q20, e-commerce made up just 14.3% of retail sales, implying that more than 85% of US retail sales remain offline.

As it stands, BNPL providers only process sales in the tens of billions. They will believe they can grow by serving new verticals, including food, auto parts, home improvement, and beyond. Moreover, they'll expect to expand their share of e-commerce spend and penetrate offline retail, too. Already, BNPL players have begun offering cards to facilitate this behavior. Strong growth is expected across geographies, particularly in North America.

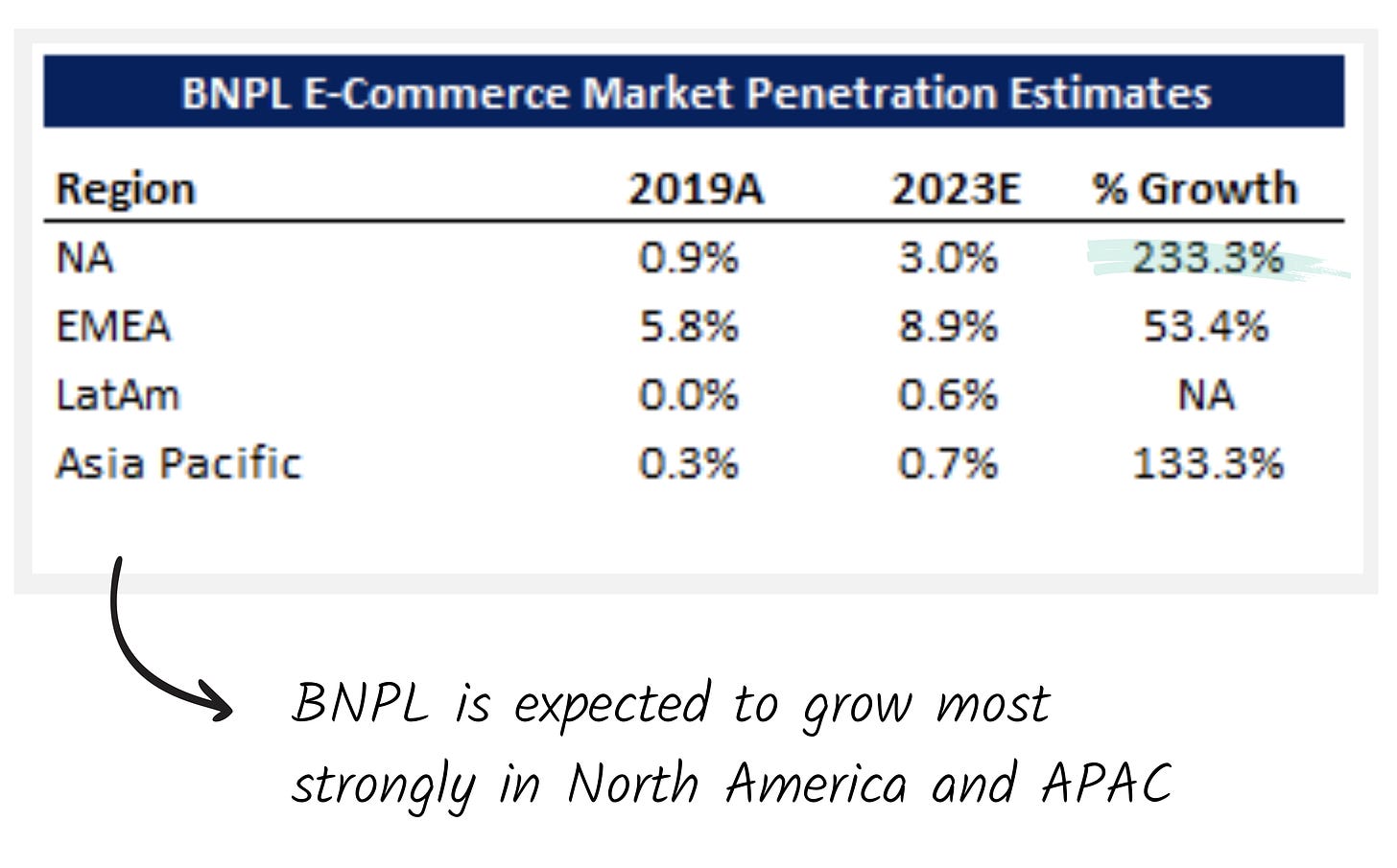

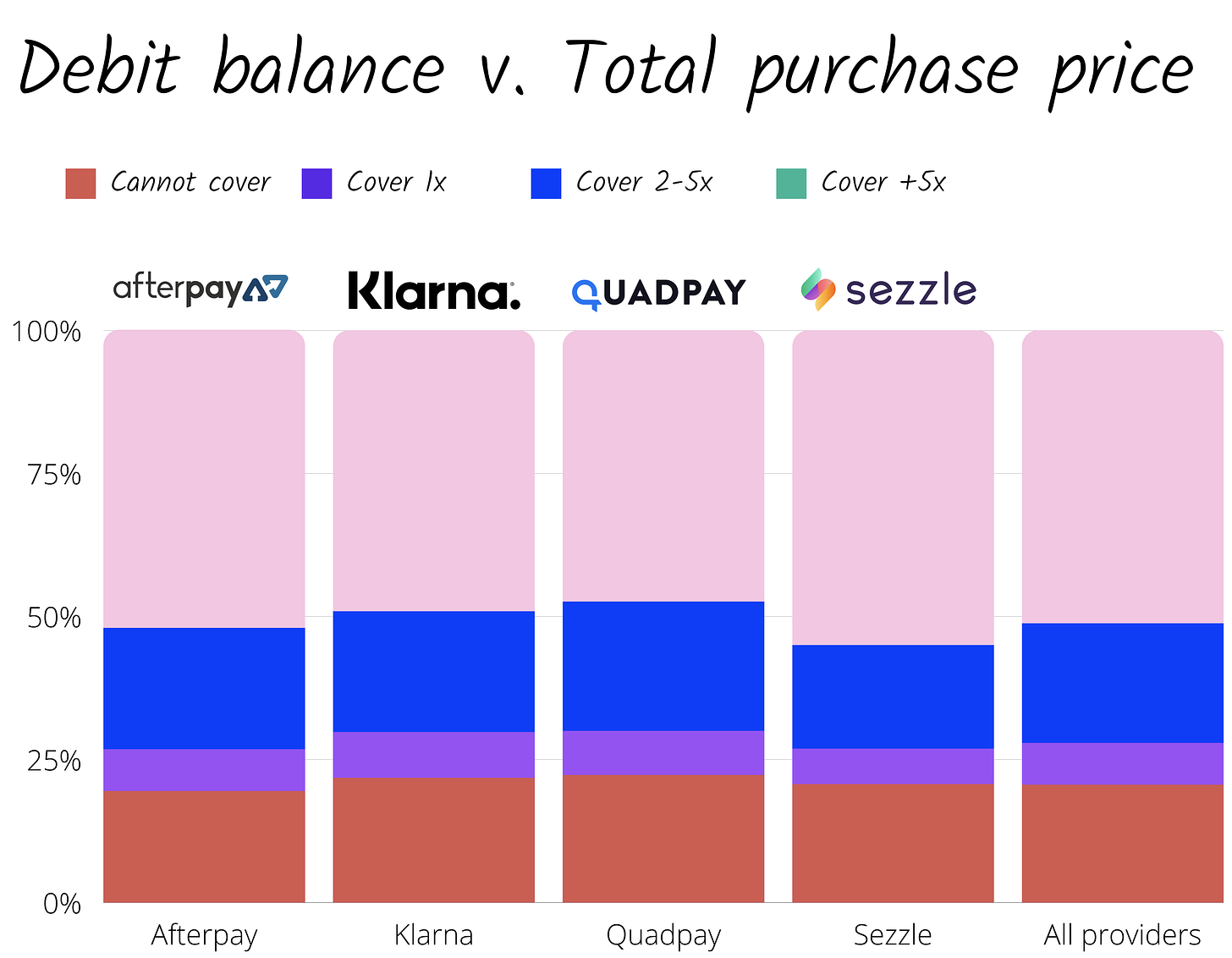

A study from Cardify provides an insight into the typical BNPL customer. Notably, Affirm is absent from the analysis, perhaps because of its focus on higher-ticket items and the decision to charge consumers interest. With that caveat, 70% percent of users are female, 80% are between the ages of 19-34, and 60-65% earn less than $50K per year. The upshot is clear: BNPL's customer base is primarily young, female, and relatively low-income.

Furthermore, the data suggests that many consumers initially try BNPL after they've tapped a significant portion of their credit capacity. While this might appear to validate industry concerns that BNPL consumers are overextended on credit, the study also illustrates that most customers could cover the cost of purchase upfront if they chose to.

Again, while some might point to this demographic and see BNPL's limitations, others will observe the opportunity. Customers are already using BNPL when they can afford to buy an item outright — won't others follow suit? Will we see more a more affluent population defer payments through companies like Affirm and its competitive cohort?

BNPL is in its early days. Affirm and its competitors will expect to increase penetration across categories, geographies, and demographics, taking an increasing chunk of the $25 trillion global retail spend. If they succeed, the prize could be significant — winners in the payment space like Visa, Mastercard, PayPal, and Square, often achieve +$100 billion in equity value over time.

Product

Affirm mentions three product offerings in the S-1:

Financing via third-party websites

Tools and analytics for merchants

Affirm website and mobile apps

Financing via third-parties

Affirm's core product is the financing offer presented to customers during its merchants' checkout experiences. This includes the company's partnership with Shopify. A customer who is in the process of buying a Peloton bike, for example, will be offered the option to finance the purchase for as little as 0% APR, alongside other payment options.

Affirm evaluates loan eligibility and the associated interest rate on a per-transaction level and based on merchant negotiations. Per Affirm's help page:

[A] number of factors are taken into account: current economic conditions; eligibility criteria—which include things like your credit score, your payment history with Affirm, and how long you've had an Affirm account; and the interest rate offered by the merchant where you're applying for the loan.

We negotiate these loan eligibility criteria and interest rates with each merchant individually. That's why you may see that some merchants offer 0% APR with payback schedules of 6, 12, or 24 months, while other merchants have no special APR and payback schedules of 3, 6, or 12 months.

Affirm's checkout credit may appeal to users, even if they can afford to purchase a product upfront, particularly at 0% APR. While such a consumer misses out on credit card points by using Affirm, they smooth the purchase's total cost.

For those unable to afford the product's purchase outright, Affirm allows them to acquire the object of their desire and defer payment. Compared to a traditional credit card, Affirm's "mistake-proof financing" promises zero late fees, favorable APRs, and a transparent payment schedule.

Tools for merchants

In the S-1, Affirm highlights eight merchant-facing features, six of which are repackaged from other product areas. For example, Affirm refers to its ability to offer 0% or interest-bearing loans to consumers as "flexible marketing capabilities' when discussed in the "merchant features' section. That leaves just two features for merchants alone: a dashboard and analytics suite.

The thinness of this offering suggests merchants don't adopt Affirm for their robust product suite but for the uplift Affirm gives their business. From Affirm's 'For Business' page:

Affirm's friction-free borrowing and borrower-friendly terms reduce the barriers to purchasing expensive items, increasing AOV, and repeat purchase rates.

Merchants pay on a sliding scale depending on their negotiations with Affirm. They end up in one of two camps:

0% APR merchant. Merchants pay Affirm a relatively large cut of the transaction (~3-5%).

> 0% APR merchant. Merchants pay Affirm a much smaller cut (closer to 0%). Affirm monetizes by offering non-zero financing rates.

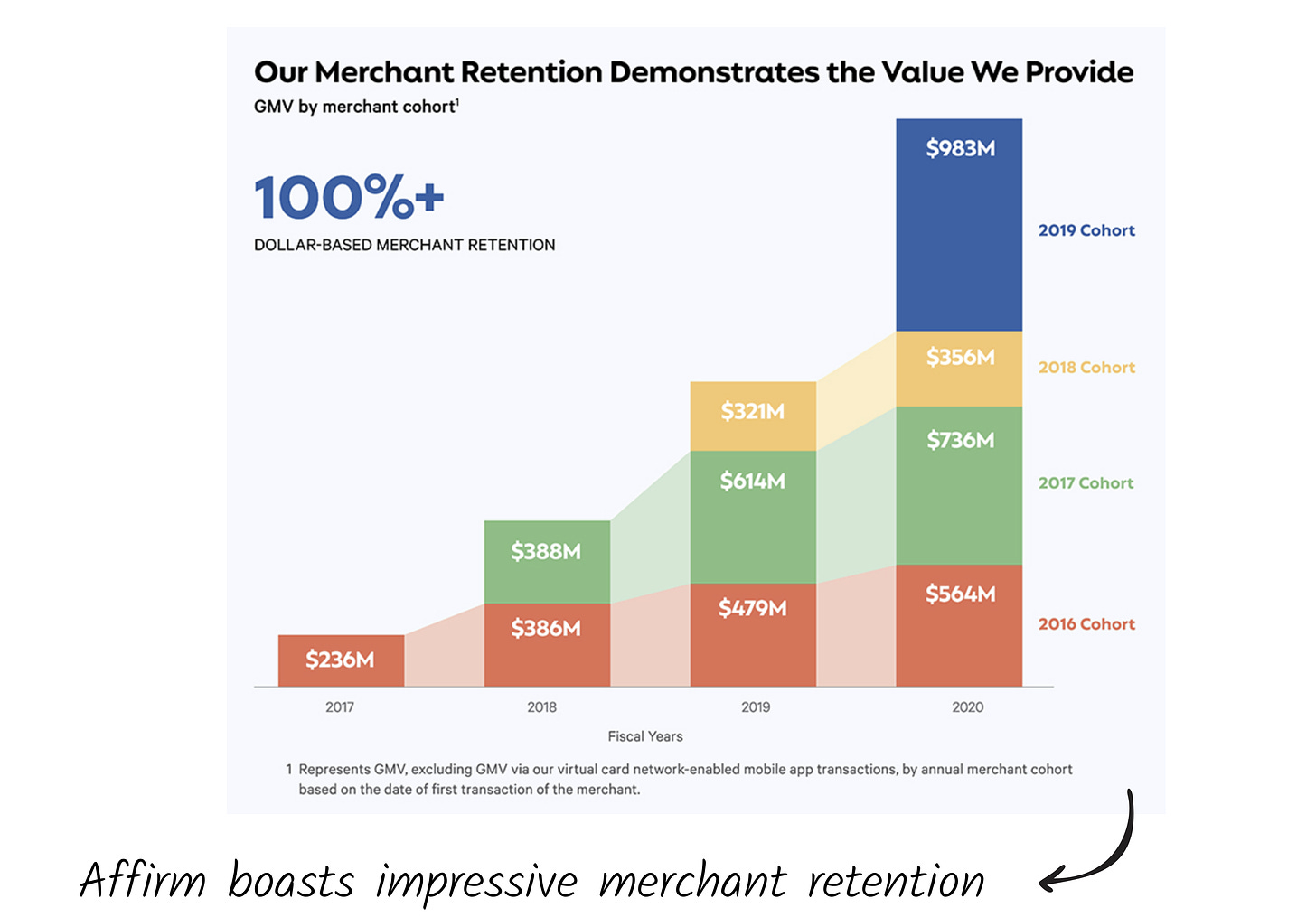

When the transaction goes through Affirm, merchants avoid paying regular payment processors, like Stripe, making a compelling offering. Perhaps unsurprisingly, Affirm boasts +100% dollar-based merchant retention rates.

Website and mobile apps

Affirm website and mobile apps are designed to capture the beginning of the consumer journey, provide a simple way to pay off loans, and lock-in future spending. The core functionality includes:

Shopping. Customers can browse offers from partner and non-partner merchants.

Payments. Customers can manage in-progress and past loans. This includes viewing upcoming payments, paying off outstanding balances, and reporting returns. An example screen is shown below.

Saving. Customers can hold their money in a savings account. Affirm this product in 2020, offering an APY of 1.00% as of November 2020. Marcus by Goldman Sachs set its rate at 0.50%.

To understand why Affirm's site and apps are essential, consider how Affirm acquires customers. Historically, Affirm has devoted little capital to winning over consumers, with just ~4% of revenue spent on Sales & Marketing (S&M).

This relative frugality reflects Affirm's role in the shopping funnel: customers begin their journey either on a search engine or merchant site, navigate to checkout, and then encounter Affirm. Traditionally, Affirm hasn't captured purchase intent any more than a credit card does.

With this context, we can understand the motivations behind Affirm's work here: to capture customers higher up the funnel. By doing so, Affirm upstreams competition, increase its value to third-party merchants, which could justify higher take rates, and can better drive repeat purchases by surfacing personalized offers to existing customers.

When customers purchase something through Affirm, the only place to manage that transaction is on Affirm's site or app. Once there, Affirm hopes customers will browse offers and make purchases. Products like the company's savings account may contribute to revenue, but it isn't their real purpose. They give customers more reason to visit Affirm, and therefore drive purchase intent.

Flywheels

There are two flywheels that Affirm describes in its S-1: a consumer-merchant flywheel and a credit modeling flywheel.

Consumer-merchant

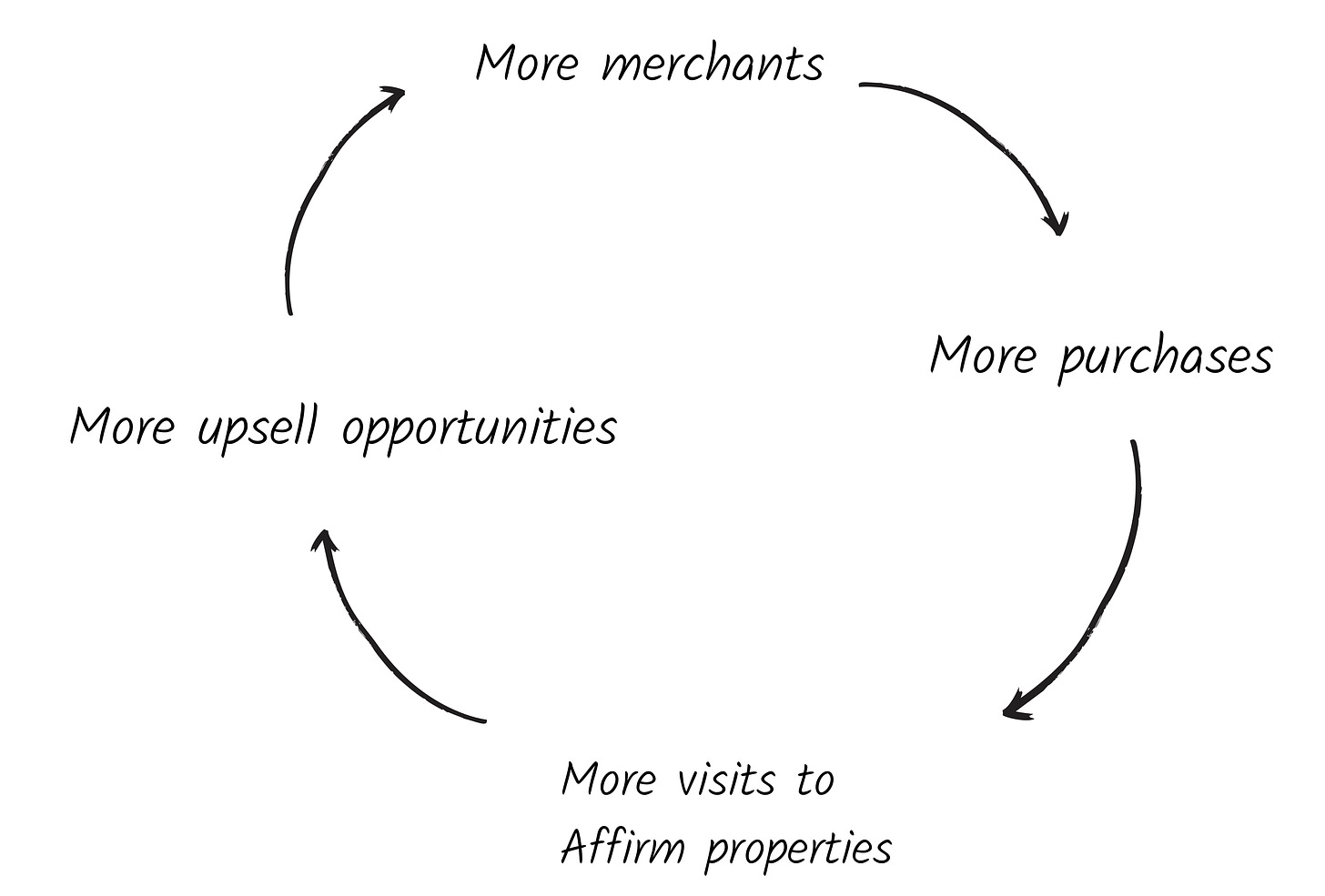

Affirm wants us to believe that they are creating the following flywheel for merchants and consumers:

Consumers that see more merchants offering Affirm finance more purchases.

The more purchases consumers finance, the more likely they are to either download the Affirm app or visit Affirm.com to manage their loans.

The more consumers visit the Affirm properties, the more chances Affirm has to encourage future purchases from merchants. (It also allows the company to upsell other offerings like its savings account.)

Driving more third-party purchases increases the attractiveness of Affirm, driving merchant adoption.

Whether you believe in this flywheel comes down to whether you think Affirm can competently drive purchase behavior from its properties. That may raise an eyebrow. After all, when was the last time you started your purchasing journey on Chase's website? Or Bank of America's? Affirm is betting it will succeed where other payment businesses failed.

Credit modeling

In the S-1, Affirm writes:

We use data to inform our analysis and decision-making, including risk assessment, in a way that empowers consumers and generates value for our merchants and funding sources. We use application and transaction data to train our model, including data from more than 7.5 million loans and six years of repayments.

The pitch is that as Affirm finances more transactions, its risk assessment improves. On the surface, it appears to be working:

This graph highlights how Affirm's net "charge-offs" (the percentage of transactions it deems uncollectible) has declined for new customer cohorts. That doesn't necessarily signify Affirm's loan algorithms are getting smarter; it could mean Affirm is winning over increasingly affluent customers thanks to partnerships like the one it has with Peloton, for example.

On this topic, the other data point Affirm cites is its delinquency rate. Per the S-1, Affirm's trailing 36-month delinquency rate is 1.1%. Without context on whether it's improving or declining, it's hard to parse this figure. According to the St. Louis Fed, overall credit card delinquency rates have oscillated between 2.0% and 2.7% over the past five years. On that basis, Affirm comes out ahead. That said, there may be some positive selection bias at play. Customers that buy from merchants using Affirm may be less likely to default on their credit card bills.

Net-net, this flywheel may raise more questions than it answers. We'd expect Affirm to learn and improve over time, but it's unclear what Affirm's unique advantages are in this arena. The company doesn't seem to collect more data than credit card companies or its competitors.

Business model

As noted, Affirm's business model revolves around building products to facilitate online transactions between customers and merchants. The company is best known for its credit product that allows consumers to finance large online purchases at the point of sale over three, six, or nine months. Affirm has quickly expanded to offer financing products for smaller online purchases paid back after 2 or 3 months, including Split Pay and Shop Pay, part of its partnership with Shopify. Affirm's recent product releases suggest the company wants to be the transaction layer for any online consumer purchase, not just the Peloton you bought during the pandemic. Affirm makes money via four revenue streams: interchange fees on virtual cards, consumer interest on purchases, merchant fees on purchases, and fees from servicing and selling their loan portfolio.

So, how does the business work?

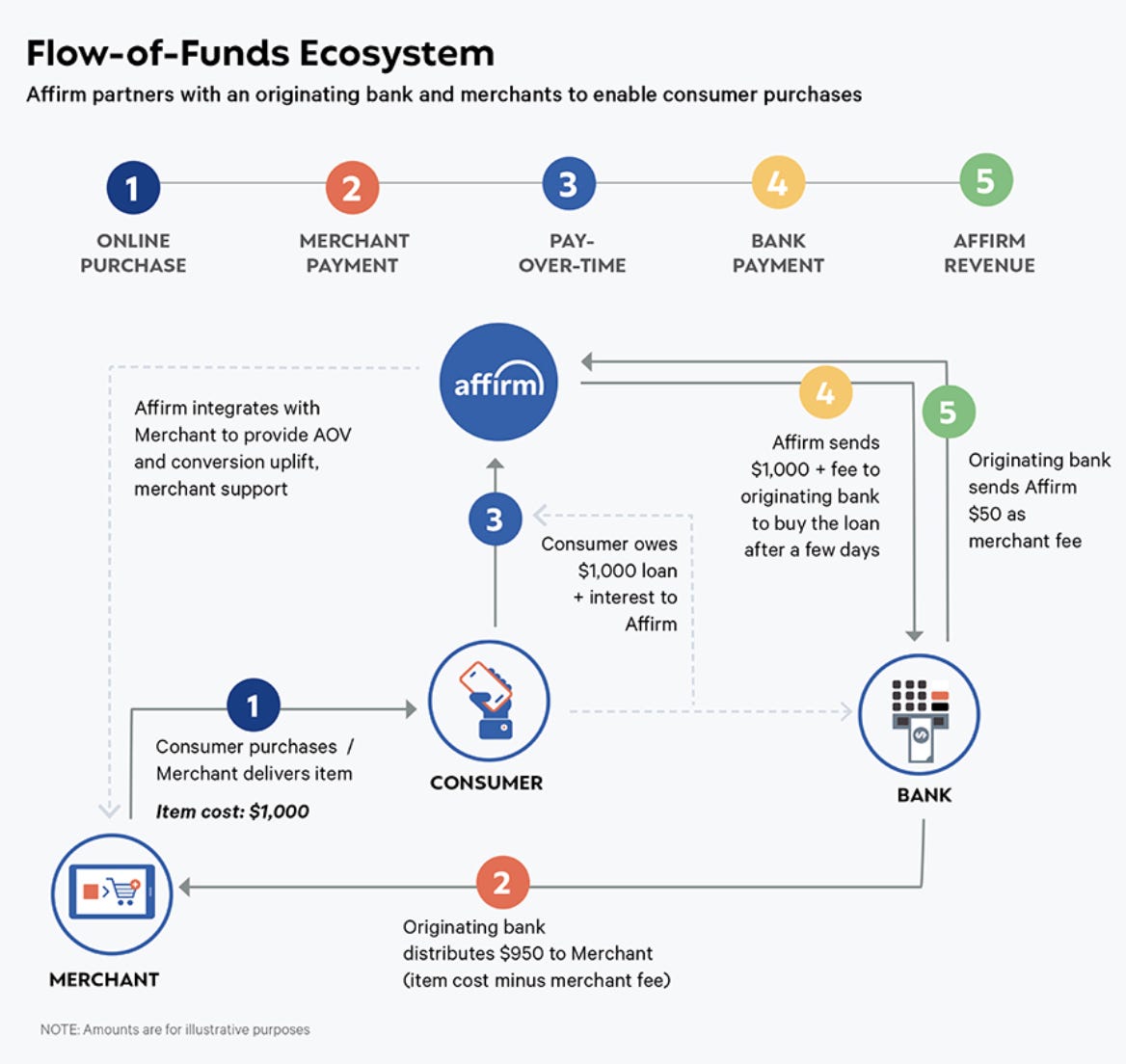

The easiest way to outline the complexities of Affirm's model is to walk through a single transaction. For Affirm to be successful, they need to engage: consumers, merchants, bank partners, and third-party capital providers.

A consumer visits a merchant and purchases a $1,000 product. At the point of sale, they select Affirm as a payment option. Affirm underwrites the consumer and provides loan pricing (0% - 30% APR) and payment options (three, six, or nine months). The consumer purchases the product with a one-time virtual card. As the issuer, Affirm earns high-margin interchange revenue. This made up 3% of revenue in 3Q20. While small, this is a strategic mechanism for Affirm to earn more profit per transaction without introducing new consumer fees that would make Affirm less attractive as a payment mechanism.

Once the purchase is complete, Affirm's bank partner (Cross River) originates the loan and distributes the capital net of Affirm's fee to the merchant. The merchant benefits because they can refrain from discounting and can provide flexibility without taking on consumer credit risk.

Affirm sets up a payment plan with the consumer. Customers pay Affirm back over the loan period plus interest depending on their risk bucket. If Affirm holds the loans on its balance sheet, Affirm earns interest from consumers. Interest from consumers made up just 31% of revenue in 3Q20, down from 45% the year prior. Affirm can generate revenue from non-consumer fees because merchants are willing to subsidize credit risk. Amazingly, 46% of GMV is generated via no-fee 0% APR products. Keeping consumer fees low is critical to growth because lower fees reduce friction to use Affirm and increase the velocity of transactions flowing through the merchant network.

Per its bank agreement with Cross River, Affirm is required to purchase the receivables from its bank partner. Affirm disburses the purchase amount and an origination fee to its banking partner. At this point, the diagram below breaks down because it doesn't highlight a critical cog in Affirm's machine: third-party capital providers. Affirm leverages third-party capital to purchase loans from its banking partner. As of 3Q20, Affirm only funded 8% of platform GMV with equity and had $4.2 billion in third-party funding capacity. This is important because it enables Affirm to invest costly equity capital elsewhere and is a critical piece of Affirm's growth story. If Affirm can't find enough third-party capital, the business can't grow. Our expectation is the business will become more capital efficient over time. Cost of capital and equity requirements will decline with scale, and invested funds will be recycled more often as Affirm introduces new high-frequency products. The average age of loans on Affirm's balance sheet is six months, but we expect it to come down, particularly with offerings like Split Pay. This will, in turn, improve unit economics.

Upon receiving funds from Affirm, Affirm's bank partner distributes the merchant fee to Affirm. Merchant fees made up 53% of revenue in 3Q20. Merchant fees are critical to the business because they enable Affirm to subsidize free products for consumers.

The flow described is for loans held on Affirm's balance sheet. Affirm also maintains capital flexibility by selling loans to third-party owners. If a loan is sold, Affirm records a gain or loss on the loan sale and charges an ongoing servicing fee to the new loan owner. Servicing fees and loan sales made up 12% of revenue in 3Q20, up from 9% 12 months ago. This is a capital efficiency feature and will never make up a majority of revenue.

Outside of capital cost (described above), Affirm's only other direct costs include servicing costs and credit losses. Combining the above, Affirm currently earns ~$192 of revenue and ~$87 of contribution profit per active customer per year on $1.6K of GMV per customer. Lastly, Affirm doesn't directly acquire most of its customers because of the merchant model, as discussed. Instead, Affirm wins customers via its merchant partners. This is valuable because Affirm can piggyback on its merchant base's consumer reach.

Lender or payment platform?

In its S-1, Affirm insists that it is a payment platform and merchant network, not a lender. Beyond long-term business model implications, this will have near-term valuation implications for the company. Payment platforms trade on revenue and steady-state operating income while lenders trade based on book value and portfolio return on equity. To invest in the IPO, you need to believe the former. The case can be made for both outcomes, so we've done just that.

Bull Case: Affirm is a merchant network and payment platform like PayPal

Affirm has built a product that is valuable to both merchants and consumers. Merchants use Affirm because it improves pricing power, repeat purchase rates, and conversion rates. Consumers use Affirm for flexibility. If you believe this value proposition is sustainable, then Affirm is no different from a payment network like PayPal or Visa that monetizes via merchant fees (>50% of revenue today). Because of its approach, Affirm has turned a lender's biggest cost center, customer acquisition, into a revenue center that lets them offer unbeatable pricing to consumers (0% APR). As Affirm provides new payment options and repeat usage grows, Affirm has the potential to capture a meaningful portion of merchant-customer transactions, which will increase merchant pricing power. In this scenario, Affirm continues to derive more than 50% of revenue from merchant fees and drives meaningfully better economics than a traditional lender due to its network investments.

Bear Case: Affirm is a lender like LendingClub

Pessimists may imagine a world in which Affirm's unique value proposition disintegrates, becoming a commodity. Banks and other capital providers with low cost of capital deposits build similar products. As a result, consumers do not repeat purchase on Affirm, Affirm's pricing power with merchants erodes, and acquisition costs grow. Affirm's revenue becomes consumer funded, growth becomes difficult, and the business resembles a tech-enabled personal loans provider.

Management

It should come as no surprise that Affirm has a deep bench of successful executives making up its management team, many of whom have a long history of working together and years of fintech experience. At the helm, we have serial entrepreneur Max Levchin. This is Levchin's third act, and in many ways, it's all about getting the band back together from his previous two startups, Paypal and Slide.

Before we dive into the management team's shared history, it's imperative to take a closer look at Levchin himself, who serves as founder, CEO, and chairman. As mentioned earlier, Levchin is a seasoned entrepreneur who knows the payments space inside and out. At the ripe age of 23, Levchin co-founded PayPal with Peter Thiel and became its CTO. At PayPal, Levchin and Thiel built out their team by recruiting heavily from respective alma maters University of Illinois and Stanford. In those formative days, they looked for highly competitive, well-read people who were proficient in math. Many of the early team members, now known as the Paypal Mafia, would go on to found successful ventures of their own, including Yelp, YouTube, LinkedIn, and Space X.

After Paypal sold to eBay for $1.5 billion, Levchin founded HVF (Hard Valuable Fun), a startup studio that produced Levchin's second startup Slide.com, among others. He later sold the company to Google for $182M. Levchin has had a hand in multiple transformative technology companies, reminiscent of another famous Valley exec Jack Dorsey. Like Dorsey, Affirm is not Levchin's only pastime. In addition to being CEO of Affirm, Levchin invests in companies through his venture firm SciFi and continues to incubate businesses out of HVF. He is a co-founder of Glow, a fertility startup, and on the boards of Unity Technologies and Mixpanel.

There are two things worth noting about Levchin's leadership. First, as alluded to, is his ability to recruit a strong management team. As mentioned above, his lieutenants (and investors) are mostly people he has worked with previously. This is a common practice. Zoom CEO Eric Yuan famously recruited heavily from former employers Webex and Cisco. It doesn't hurt that those in Levchin's inner circle have some of the most impressive pedigrees in fintech.

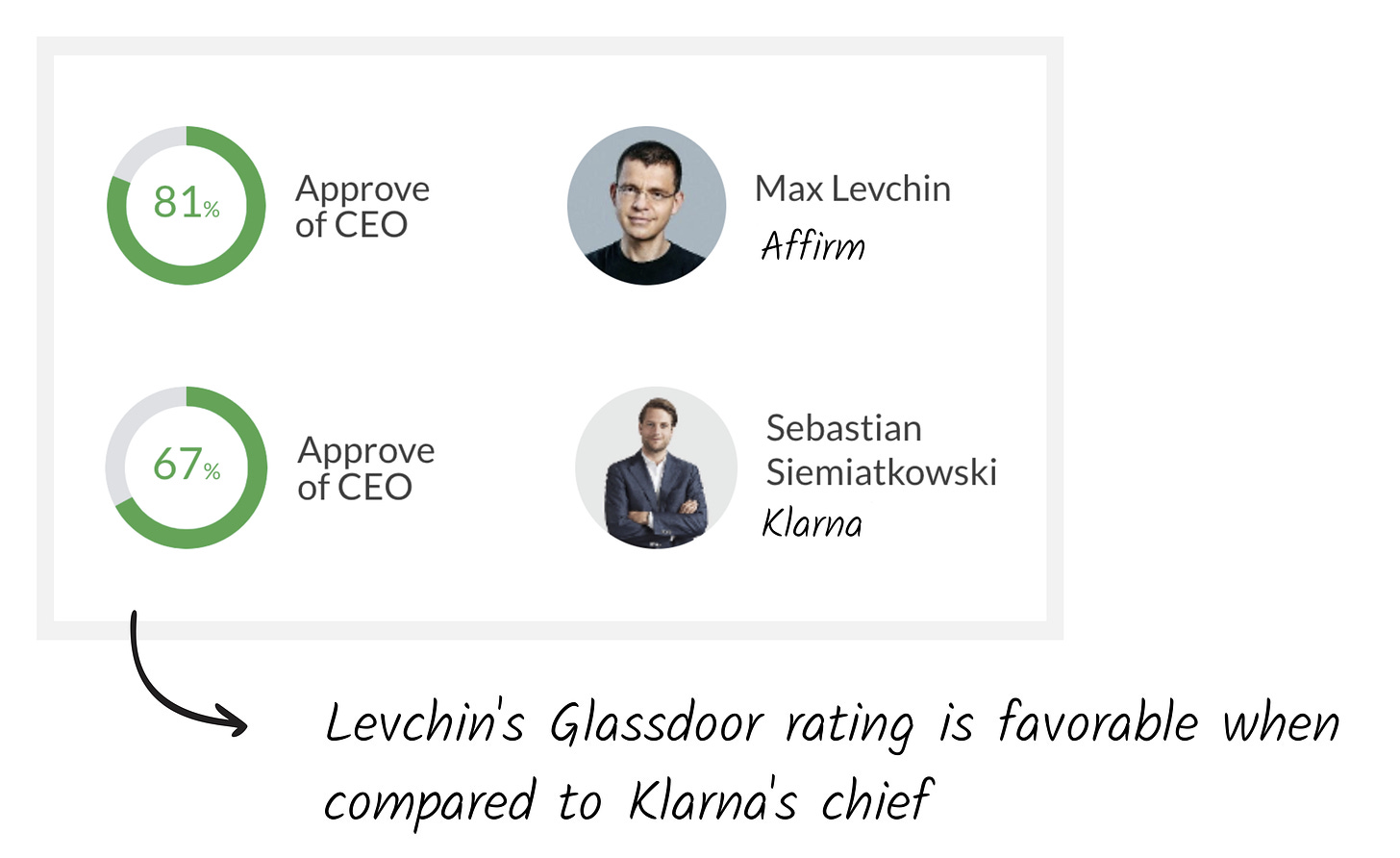

Second, Levchin appears to be reasonably well-respected by his employees. Per GlassDoor, 81% of reviewers approve of him as CEO. The ability to recruit and retain talent is paramount, given the war for talent at growth-stage technology companies continues to escalate.

The board seems to recognize Levchin's importance, structuring his compensation to incentivize a long tenure as CEO. The majority of his payment comes from a Value Creation Award with ten different tranches granted based on the stock price over the next five years. His current base salary is $10,000.

Let's take a look at the remainder of the all-star executive team that Max recruited to build Affirm.

Levchin tapped former Slide CTO, Libor Michalek, to lead Affirm's technical efforts. Another University of Illinois grad, Michalek, has a history of joining early-stage technology companies as an individual contributor and rising through the ranks to senior management. In his role as CTO, he oversees engineering, product, design, operations, and analytics. Like Levchin, Michalek is obsessively metrics-driven, dedicating thirty minutes every day at 7:30 am to review them.

Another former colleague, Keith Rabois, sits on Affirm's board. The newly-minted Miami resident is having a banner year. In addition to Affirm, Rabois has invested in six other companies going public in 2020, including Airbnb, Palantir, and DoorDash. Levchin and Rabois have known each other since PayPal, where Rabois held the EVP of Business Development title. Rabois and Levchin also joined forces on Slide, where Keith led go-to-market strategy as an EVP. Rabois served as COO of Square before becoming a full-time (and, of course, contrarian) investor.

Rabois may have had a hand in recruiting Chief Legal Officer Sharda Caro del Castillo, given she worked as Payments Counsel at Square. She also had a stint at PayPal but after the eBay acquisition. Caro del Castillo joined Affirm in late 2019 and brings years of merchant acquisition, payment cards, and platform payments experience. She has the domain expertise to navigate the regulatory environment for Affirm as it adds financial products to the platform.

Silvija Martincevic serves as Chief Commercial Officer. The BNPL space is amid a land grab, making Martincevic's role vital. Martincevic brings years of experience as the former COO of Groupon, where she managed a $1.2 billion P&L. CMO, Greg Fisher, another ex-PayPal employee, will also play a vital role in this battle. He previously served as CMO of Braintree and Venmo.

The final person to note is Christa Quarles. She is Affirm's first and only independent board member, brought aboard in the spring of 2019. Quarles was notably the CEO of Opentable after joining the company as the CFO in 2015. Quarles also served as an SVP at The Walt Disney Company and currently sits on the board of personal care corporation Kimberly-Clark ($KMB).

Overall, Affirm's management and board bring a wealth of relevant operating experience to the table, particularly in fintech. It's hard to imagine a team better equipped to capitalize on the opportunity.

Investors

In digging into Affirm's investor base, the obvious place to start is with fellow PayPal Mafia member, Peter Thiel, who requires no introduction.

Affirm wasn't the first time Levchin asked Thiel for investment. Thiel didn't come on as a co-founder of PayPal until after 23-year-old Levchin crashed his Stanford seminar, then pitched him over breakfast the next morning.

Thiel first participated in the Affirm's $7.5M Series A in 2012. Thiel would invest again — through his venture capital firm, Founders Fund — leading the company's Series D in 2016. Keith Rabois led Khosla Ventures' Series B into Affirm, before joining Thiel's firm, Founders Fund.

Beyond Khosla and Founders Fund, other winners include Lightspeed Ventures and Spark Capital, who joined in at Series B and Series C, respectively.

An unlikely name appearing on the cap table is e-commerce giant Shopify. As mentioned, Shopify and Affirm entered into a partnership earlier this year, with Affirm earning exclusive rights to power Shop Pay installments in the US.

The S-1 reveals that, as part of this deal, Affirm gave Shopify warrants to purchase up to 20.3 million shares for $0.01 each (!). It's reported that Shopify's holding could be worth up to $500M — a pretty good windfall for a channel partnership.

One interesting and unusual note regarding Affirm's financing history is that it announced a $500M Series G raise in September 2020, just two months before filing for its IPO. This caused many to assume Affirm wouldn't list until 2021. Despite this very recent capital injection, Affirm opted to join the year-end rush.

Financial highlights

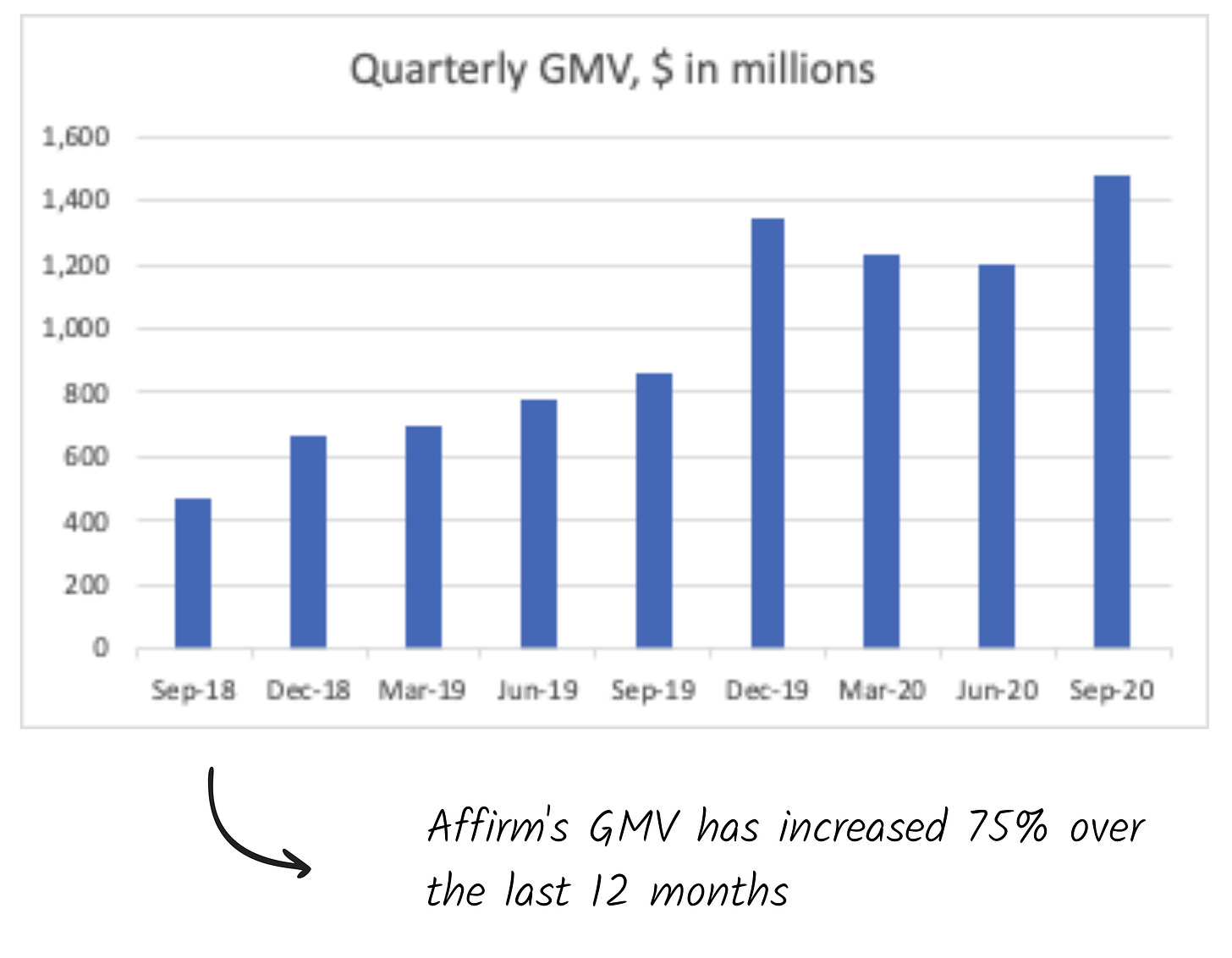

The primary driver of Affirm's performance is the gross merchandise volume (GMV) that flows through its platform. GMV rose by 75% in the last 12 months, driven by more consumers doing slightly smaller transactions. In the past year, Affirm processed just over 8.5 million transactions at an average ticket size of $615 per transaction.

GMV typically gets a seasonal bump in the December quarter due to holiday shopping, so how the platform fares in the current period is critical. Beyond that, GMV is also influenced by new merchant sign-ups. This will be the first holiday season with Shopify signed up as a client; how much of its $2.4 billion of Black Friday sales went through Shop Pay will soon become apparent.

Affirm's financial focus is the contribution profit extracted from its GMV. In the last 12 months, it earned contribution profit equivalent to 4.5% of GMV. The number is quite volatile as it depends on product mix: 0% APR loans typically earn contribution profit at a higher rate than Split Pay and other short duration, small ticket size loans.

The fundamental building blocks of contribution margin are merchant network revenue, lending income, income from buying and selling loans, and processing and servicing costs. In addition, there is a small but growing revenue line from virtual card issuance. Taking these in turn:

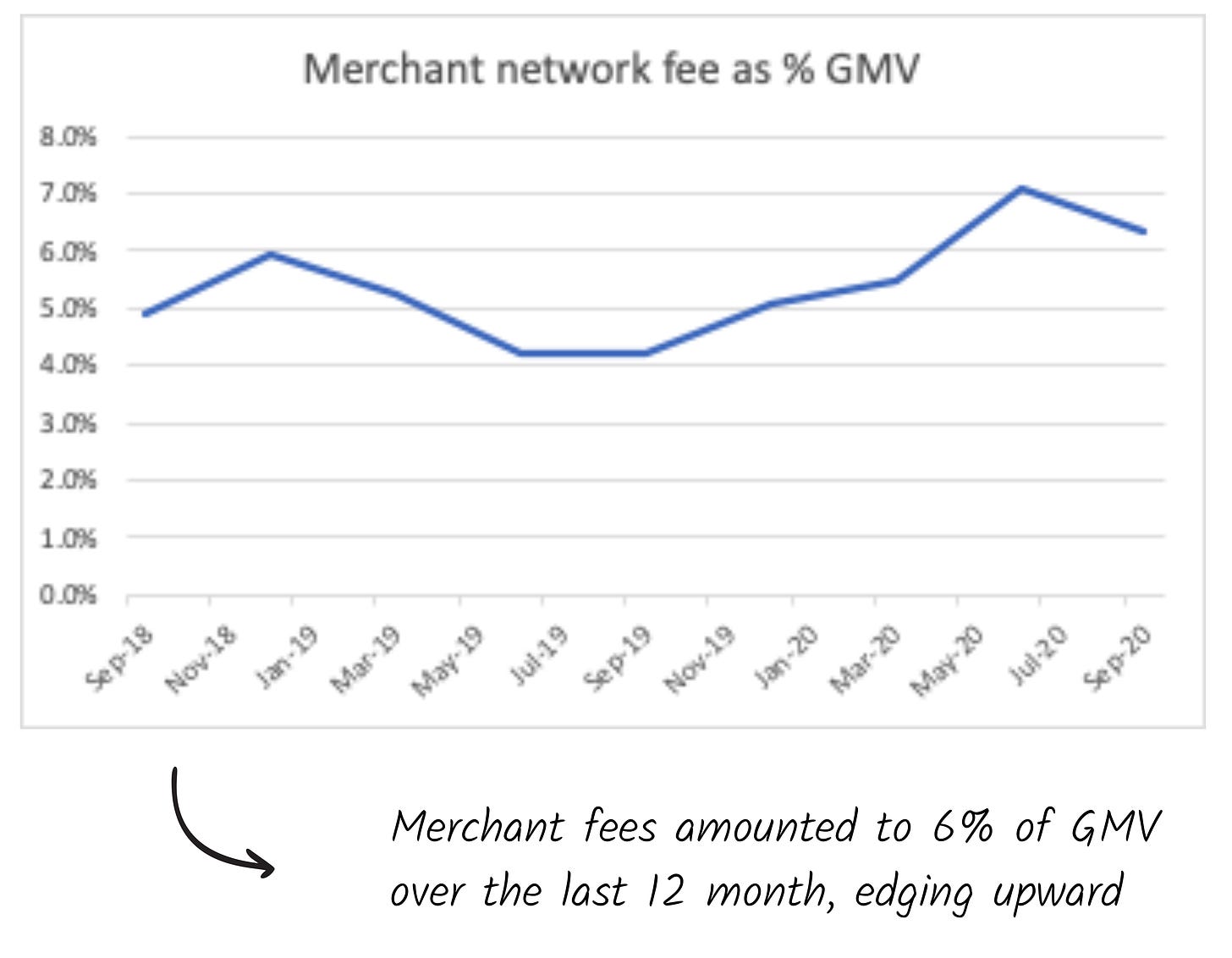

Merchant network revenue

Affirm's largest revenue source is the network fees it charges its merchants. In the last 12 months, these fees amounted to 6.0% of GMV. The rate on 0% APR loans is higher, and so, as they have grown to take a more significant share of GMV (45% in the most recent quarter, versus 27% the prior year), the merchant revenue rate has risen.

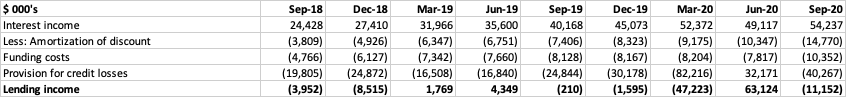

Lending income

Unlike the merchant network fee, which is paid upfront, revenues on the lending side accrue gradually over the life of the loan. Loan durations can be as long as 48 months, although the average is six months, which means that income is typically spread over two quarters.

Clearly, interest income on 0% APR loans is zero, but these loans still need to be funded, and they still expose Affirm to credit risk, so they come at a cost — hence the higher merchant network fees to compensate. Although Affirm takes provisions for credit losses upfront, at the same time as it books the merchant network fees, funding costs get spread out over the lifetime of the loan. This means that in a period in which Affirm is rapidly growing its 0% APR lending, income will be front-loaded.

From an accounting perspective, there's an additional element to all this. When it buys these loans from its originating bank partner, Affirm does so at a premium to market value, crystallizing a loss. It then writes that loss back through interest income over the life of the loan. While the company strips this out of its contribution profit, it effectively inflates reported revenues.

Due to the weight of 0% APR loans in the mix, lending overall — excluding the benefit of merchant network fees — is not very profitable. Once provisions for credit losses and funding costs are netted off against underlying interest income, there's only around $3 million left over, based on the past twelve months' performance.

However, this is a function of the mix. On interest-bearing loans, Affirm earns an average rate of ~23%. Set against funding costs of ~4%, these can be quite profitable. The real risk here is that loans default. Given that Affirm approves 20% more customers for credit than comparable competitors, the risk is particularly pronounced.

So far, Affirm's credit model has held up well. As of the end of September, 1.0% of loans were over 30 days past due, roughly on par with the three year weighted average of 1.1%. Overall, the credit card industry was at 2.0% at the end of September and has experienced average delinquencies of 2.5% over the same three year period.

Moreover, individual loan cohorts' performance appears to be improving, based on the “charge-off” chart supplied by the company, highlighted as part of our discussion of Affirm’s flywheels. It indicates that the worst cohorts suffered cumulative losses of up to 4.5%, but more recent ones are tracking below 3.0%. Credit rating agency DBRS Morningstar estimates a worst-case cumulative net loss of 6.58% on the pool of loans they looked at, including additional stress from the pandemic's impact.

As it happens, the coronavirus was less of an aggravating factor than anticipated. In March, the company increased its allowance for potential loan losses to an amount sufficient to absorb losses on 14.8% of its loan book. The following quarter it was able to release some of this allowance, bringing the amount down to 8.8%. Future performance hinges on credit losses not deviating too much from this.

Income from buying and selling loans

As noted, Affirm's loans are technically originated by bank partner, Cross River Bank. Affirm has an agreement to buy them from Cross River, which it does for a fee a few days after origination. Affirm may then keep these loans on its balance sheet or sell them to third parties. In the financial year to June 2020, Affirm sold 56% of the loans it bought. However, in the most recent quarter to September, it sold far fewer—only 28%. The change could be due to the capital Affirm raised in September, giving it the capacity to fund more loans off its balance sheet. Loans that are sold trigger a gain or loss that shows up as a revenue item on Affirm's income statement. Looking through the accounting intricacies, Affirm tends to make a loss on the sale of loans, which is unsurprising given how many of them are 0% APR.

Even after selling off loans, Affirm continues to service them to stay close to its customers. Third-party buyers pay a servicing fee of ~1.2% on their loans' unpaid principal balance, which appears as a revenue item on Affirm's income statement.

Costs

The final component of the contribution profit is the variable costs associated with making loans. In the last 12 months, they have been ~1% of GMV. As a proportion of total costs, they are relatively small, contributing 15% to total operating expenses.

Most of the cost base is fairly fixed, with technology and data spend, together with general and admin costs, making up three-quarters of the cost base over the last year. If Affirm can facilitate higher GMV on that fixed cost base, there's operating leverage in the model.

The final element of costs is sales and marketing, which made up 12% of the past 12 months' cost base. With the platform having facilitated 8.5 million transactions over the period, marketing costs amount to $5 per transaction, a meager acquisition cost—unsurprising given the work the merchant puts in.

Competition

Affirm's major BNPL competitors include Afterpay, Klarna, Quadpay, and Sezzle. Of these, Klarna is the largest player globally by GMV, but within the US, Affirm and Afterpay seem to have the largest market share. Interestingly, Afterpay, an Australian company, appears to be outpacing Affirm's domestic growth.

Given all of these competitors have roughly the same products — installment payments with low/no fees, simple-interest loans, and mobile-based consumer marketplaces — distribution seems to be the primary basis for competition.

As noted, we see the industry as being in a "land grab" phase in which BNPL providers need to secure the highest number of quality retailers so that they can offer the most comprehensive marketplace. Against that backdrop, Affirm's partnership with Shopify appears very strategic.

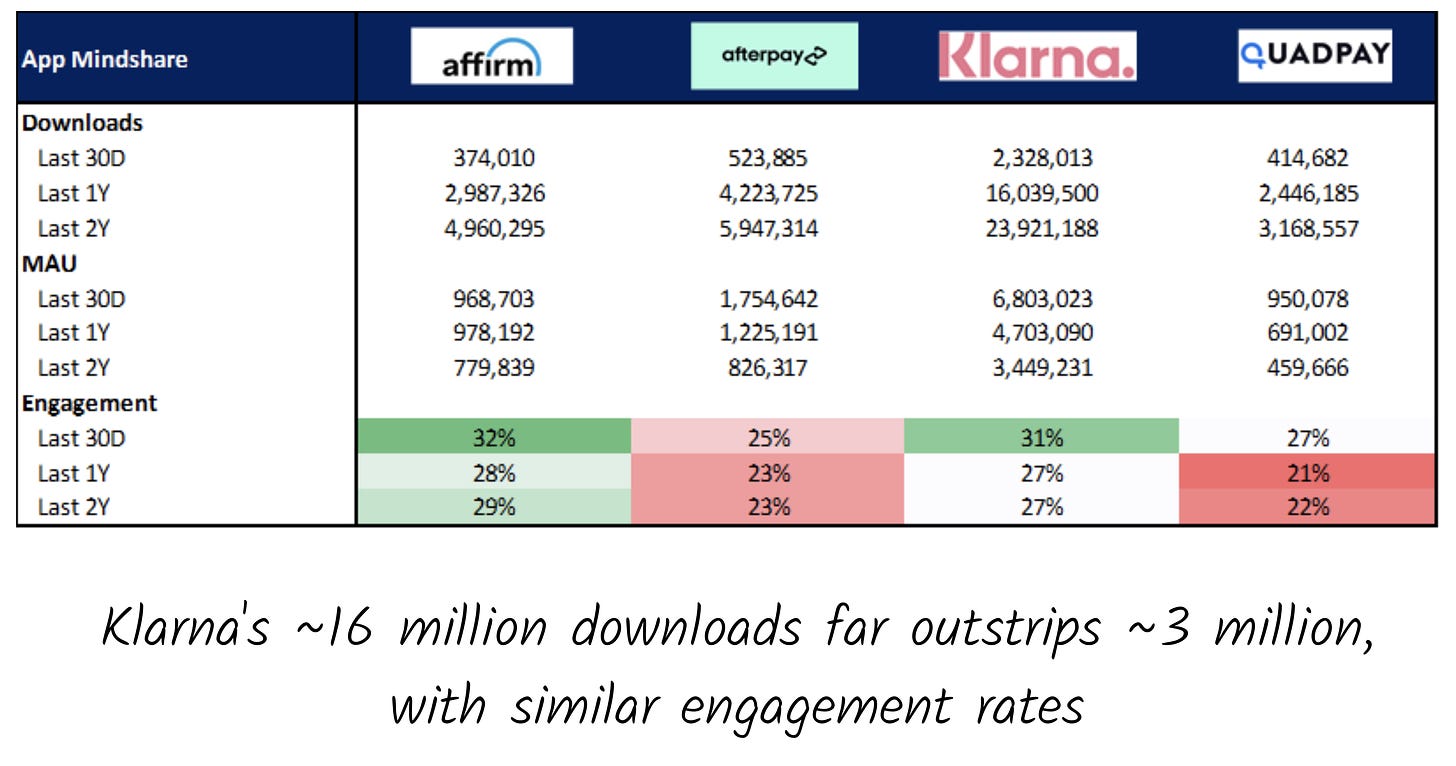

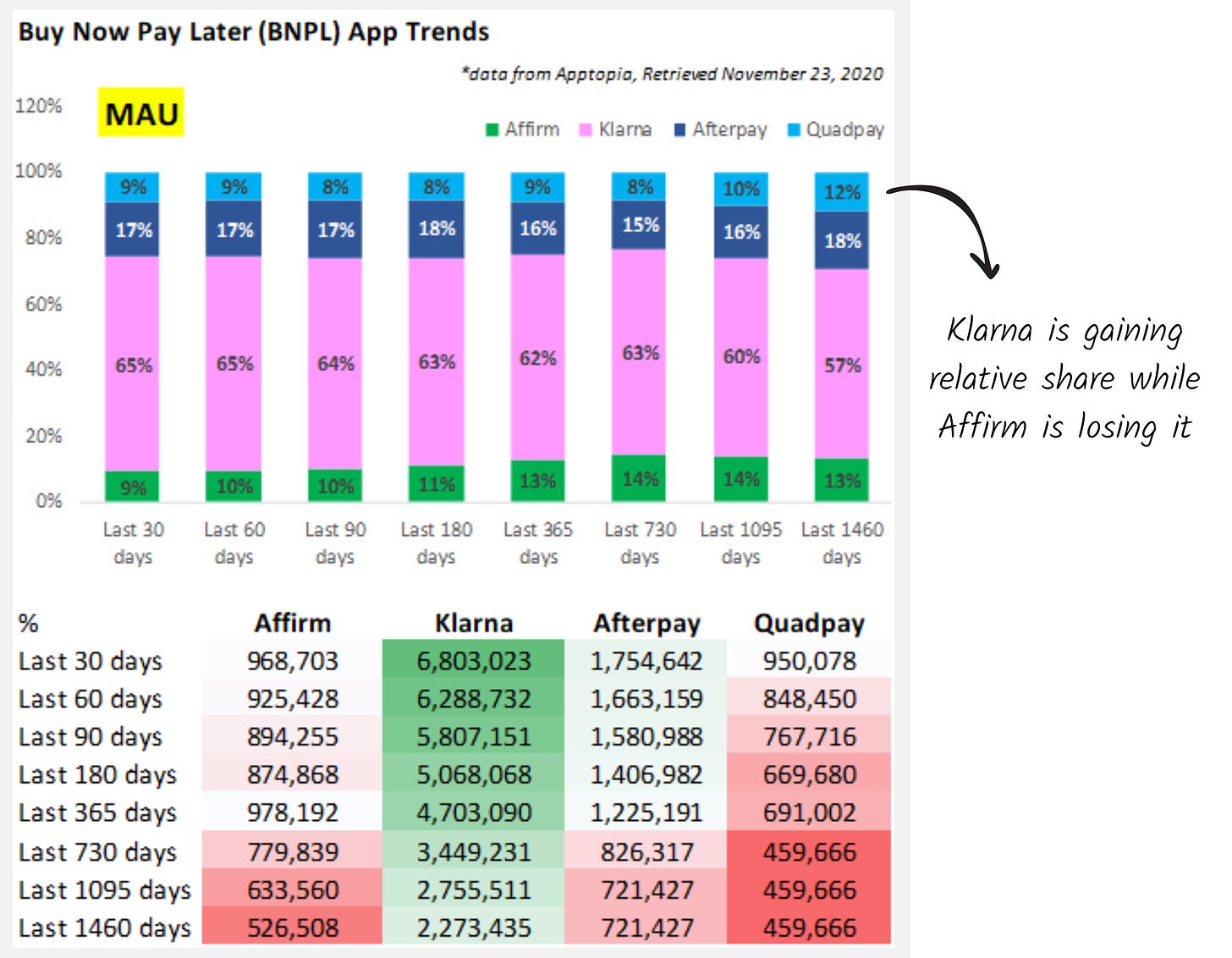

Several BNPL players tout their mobile app and consumer marketplace as differentiating factors. The S-1 Club reviewed app download data to contextualize relative mindshare. According to Apptopia, Klarna dominates in global downloads and MAUs, though Affirm enjoys leading engagement.

Data from Second Measure provides another barometer. Measuring consumer transaction information, Second Measure’s data indicates that Affirm leads competition when looking at sales per customer and the average value of a transaction. It lags when looking at the number of transactions per customer. This reinforces the notion that Affirm is more commonly used to finance large purchases, at least when compared to its competition. Beyond that, all BNPL players observed appear to be expanding sales, customers, and transactions.

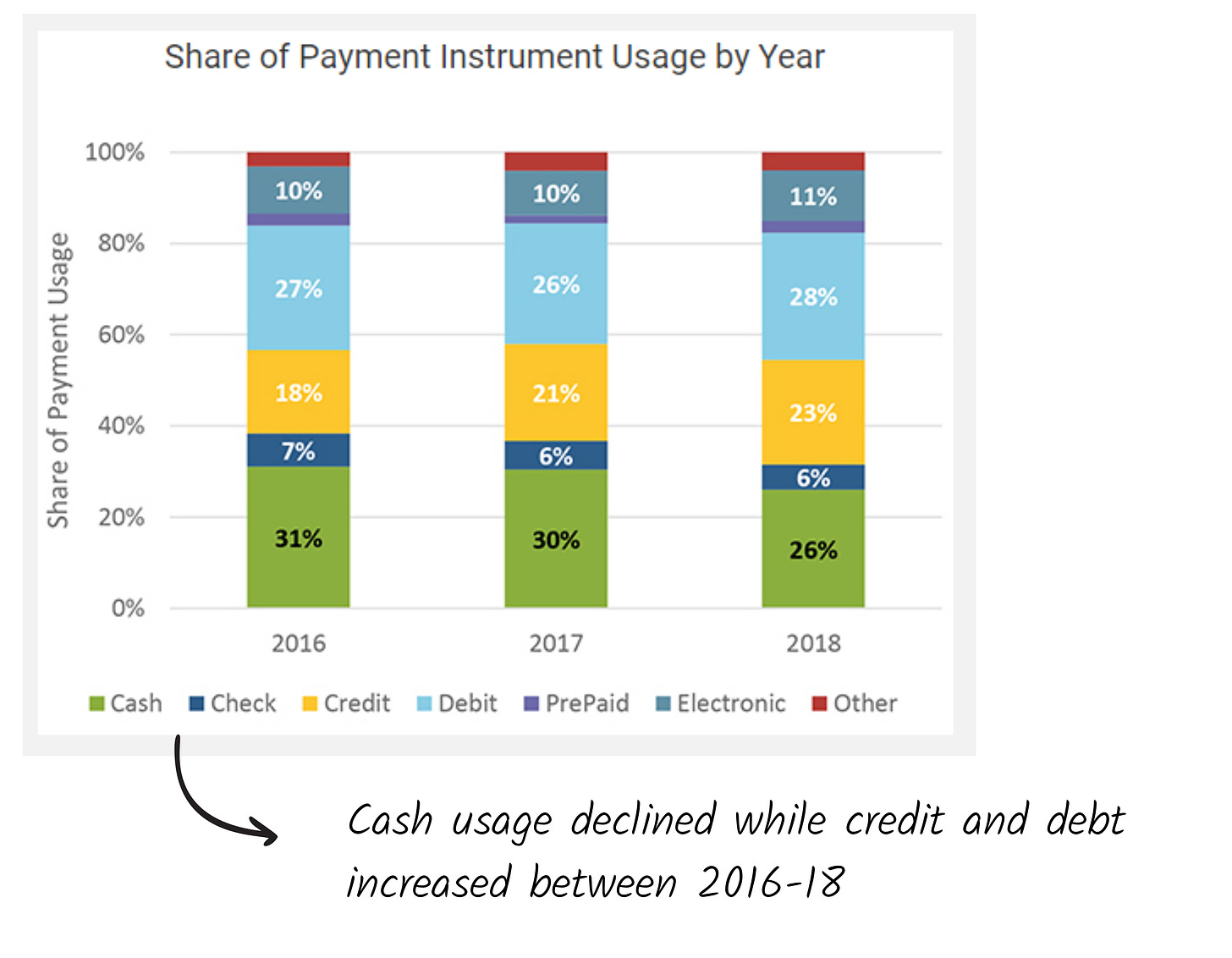

While other BNPL players pose a threat to Affirm, the company's real competition may be the status quo. A study conducted by the Federal Reserve in 2018 found that debit cards were the most widely used payment mechanism in the US, making up 28% of transactions, followed by cash (26%) and credit cards (23%). While not explicitly named in the study, BNPL is a nascent payment option with only 1% of the transaction mix but growing rapidly.

While Affirm positions itself as a credit card alternative, the chart below leads us to believe the company can take share from other payment mechanisms.

While BNPL and Affirm have ample opportunity ahead of them by displacing credit cards, it's challenging to identify a true barrier to entry. Amazon already offers a BNPL option upon checkout. JPMorgan Chase's credit card suite provides a similar option with modest interest rates. Apple offers 0% interest monthly payments. PayPal is a colossus in its own right before even considering competition from its Venmo arm.

Regulation

Affirm operates in one of the most highly regulated industries in the US – consumer lending. The S-1 makes this pretty clear:

Our business is subject to extensive regulation, examination, and oversight in a variety of areas, all of which are subject to change and uncertain interpretation.

One area of particular scrutiny is Affirm's embrace of the "rent-a-bank" model. Affirm leverages Cross River's banking licenses and the range they provide. In particular, those licenses enable Cross River to lend in states where usury laws forbid high-interest lending. The maximum allowable interest rate in New Jersey is 30%, so that's the rate that gets exported.

Scrutiny has centered around who the true lender is in situations like this and whether, once the loan has changed hands, its original terms are still applicable. The question emerged following the case of Madden v. Midland Funding in 2015 when the Second Circuit (New York, Connecticut, and Vermont) deemed that once the loan had changed hands, home state rate advantage disappears. Since then, key banking regulators, notably the FDIC (Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation) and the OCC (Office of the Comptroller of the Currency), have ruled in favor of the model, but some individual states are still pushing back.

Some clarity emerged in August this year when related litigation was settled in Colorado. The state had brought a case against two marketplace lenders that had partnered with originating banks, one of which was Cross River. The upshot was that as long as rates were capped at 36%, the structure could remain. The settlement creates a roadmap, but other states may form different views.

In the meantime, Affirm's securitization trust ($400 million loan pool) does not include any loans to consumers in Iowa or West Virginia, where risk is higher. Loans to consumers in New York, Connecticut, and Vermont are limited to their respective state usury rate cap.

The salience of these potential regulatory risks will likely be determined by political realities distinct from the specific technical, financial, and legal questions at issue. Whether or not Affirm's murky status as a non-bank lender, for example, becomes a serious problem will mostly be a question of whether or not a regulatory body or elected official wants to make it a problem. Selective enforcement by political actors will make these concerns major issues or minor technicalities.

As a consumer lender going public through a splashy IPO, Affirm will be entering the public markets with a target on its back. By definition, it is becoming a sweet target to investigate. The prospect of a more muscular (that is, existent) CFPB under Biden than what we saw under Trump magnifies that risk, but it extends far beyond the federal government.

It doesn't take much imagination to see how Affirm's cancellation and returns policies during the pandemic could cause problems. As it stands, Affirm essentially leaves customers out to dry, asking them to deal with merchants' customer support to cancel their loan. That might lead to a rash of consumer complaints, and eventually, an investigation from a state AG or federal regulator. This may already be happening: complaints with the BBB against Affirm seem to be growing 20% faster than GMV over the past 12 months. The interstate regulatory arbitrage (originating loans in NJ to flaunt local usury laws) could become a matter of principle for a state official that sees a juicy opportunity to make an example of a tech company believing itself above the law. Each of these open questions and unsolved risks opens up a line of attack for someone motivated to find one — the matter at hand may well be immaterial.

COVID-19

The obvious "covid angle" for Affirm is Peloton and the rise of at-home fitness hardware, generally. During the pandemic, people can't go to the gym (or shouldn't). As a result, Peloton is exploding, and, as an expensive, durable good, is the ideal purchase for Affirm to finance. Peloton comprises 28% of Affirm's overall revenue in FY 2020. The next nine largest merchants make up only 7% combined.

Taking a step back from Peloton for the moment, Affirm is good for purchases that are: 1) large, 2) durable goods, and 3) made online.

The pandemic is shifting spending away from services (restaurants, travel, entertainment) to goods. Physical luxury goods are replacing vacations as splurge purchases, for example. On top of that, the pandemic is shifting spending towards e-commerce in a dramatic fashion, giving Affirm more top of funnel opportunities. It's long been a truism of upscale commerce that customers need to get hands-on with big purchases to feel comfortable buying. That's historically been a barrier to e-commerce penetration for luxury goods. Affirm, by lowering a mental barrier to entry, helps merchants overcome that. Finally, extremely low-interest rates mean lower credit costs, making 0% interest loans easier to stomach and more profitable.

On the consumer side, the relative wallet share of purchases suitable for Affirm is growing, even as overall consumer spending declines. On the merchant side, Affirm presents a unique and suddenly-necessary opportunity to bring brick and mortar operations online, with financing replacing tactile experiences as a means to grease the wheels toward conversion.

What does this all mean for Affirm?

As our analysis of payment mechanisms shows, there haven't been any radical shifts in the instruments consumers use to make purchases. This reflects ingrained behavior and comfort with existing methods and implies that consumers aren't loyal to any particular payment method. Affirm will hope that is, indeed, the case. Fulfilling its potential will require a change in consumer behavior.

Ultimately, there is no question that BNPL has a market. Affirm seems well-positioned within it to capitalize, though Klarna boasts a larger userbase, and Afterpay may be growing more quickly. The bigger question is whether Affirm will be a long-term winner, stealing considerable share from existing methods of exchange. The market is young, and the dynamics are fluid. It will be essential to track how the various competitors in the market react as this industry evolves.