Airbnb in 1 minute

That Airbnb is here at all is remarkable. Bludgeoned by the coronavirus, the hospitality platform has spent much of 2020 in a state of crisis, raising debt and cutting budgets. In the process, management demonstrated trademark resilience in the face of adversity, artistry amid disaster.

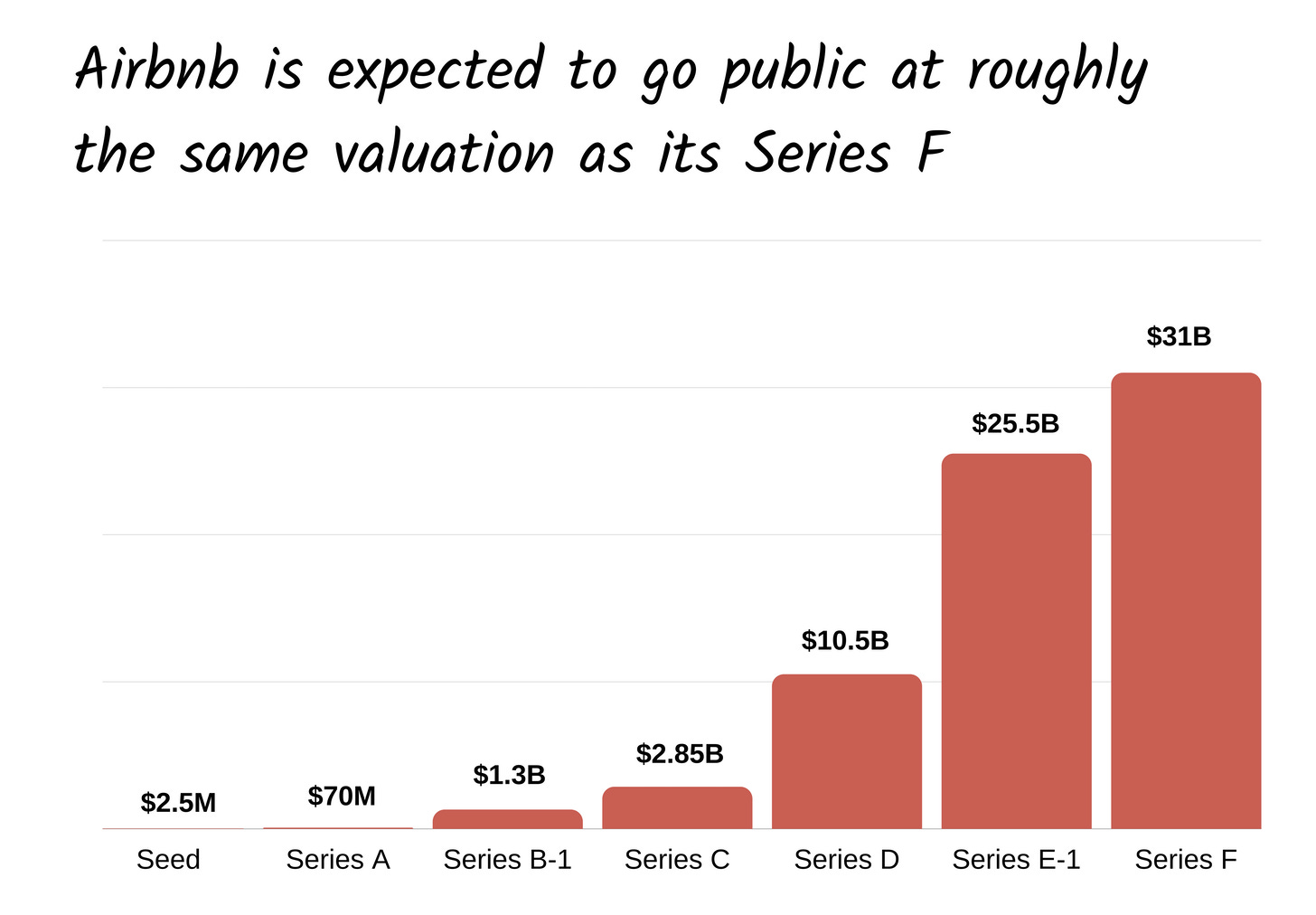

Thirteen years after inception, Airbnb is, like the rest of the world, in flux. Revenue totaled $2.5 billion over the first nine months of 2020, down 32% year-over-year. Operating margins took a hit, too. But with vaccine trials looking promising, better days may be around the corner. Winners of the IPO include Sequoia Capital and Founders Fund.

To learn about the “worst idea” for a business, read on.

Analysts

Introduction

The Ancient Greeks had a word for it: Xenia.

While we might translate the term as "hospitality," that would be missing the point. Xenia is a philosophy, a set of sacred rules, more meaningful than hospitality's connotations of swiftly-manifested club sandwiches, pillows adorned with chocolate.

In that respect, xenia is not a matter of one-sided deference, host acceding to the whim of guests, but a collaboration, a mutualistic engagement in which both parties hold behavioral obligations. According to xenia's tenets, hosts agree to provide shelter and food with grace while guests agree to entertain, to act politely, to avoid being burdensome, to reciprocate should their hosts ever need a place to stay. While nearly every hospitality company seeks to fulfill its part of the equation, the modern guest feels no such obligation, no sense of reciprocity.

Except on Airbnb.

In its creation of a marketplace where both parties are rated, in which roles trade hands — guest becoming host, host becoming guest — Airbnb has revived xenia. Hospitality can be more than a blithe catch-all for the fast-shuttling bellhop or urbane concierge; it can be a virtue and a verb.

In this respect, Airbnb's S-1 is more morally instructive than many others. There's a lawful good, Mr. Rodgers-esque avuncularity throughout that emphasizes the importance of "connection" and "belonging." Here's one particularly misty-eyed passage:

Looking back over the past 13 years, we have done something we hope is even more meaningful: we have helped millions of people satisfy a fundamental human need for connection. And it is through this connection that people can experience a greater sense of belonging. This is at the root of what brought people to Airbnb and is what continues to bring people back.

If another business tried this tact, it might provoke a cringe, but it doesn't in the context of Airbnb. There's something inarguably likable about the company and its founding pair Brian Chesky and Joe Gebbia. While part of that may be due to some natural affability, there's also the sense that Airbnb's success has been particularly hard-earned, requiring unusual amounts of self-belief and grit. Now the canonical "good idea that sounds like a bad idea" business, Airbnb's founders first demonstrated perseverance by peddling novelty cereal to make ends meet and swimming against the consensus position. As Chesky later said about Airbnb's early days, "We were these crazy people, three guys with three airbeds in the living room. People thought this was the worst idea."

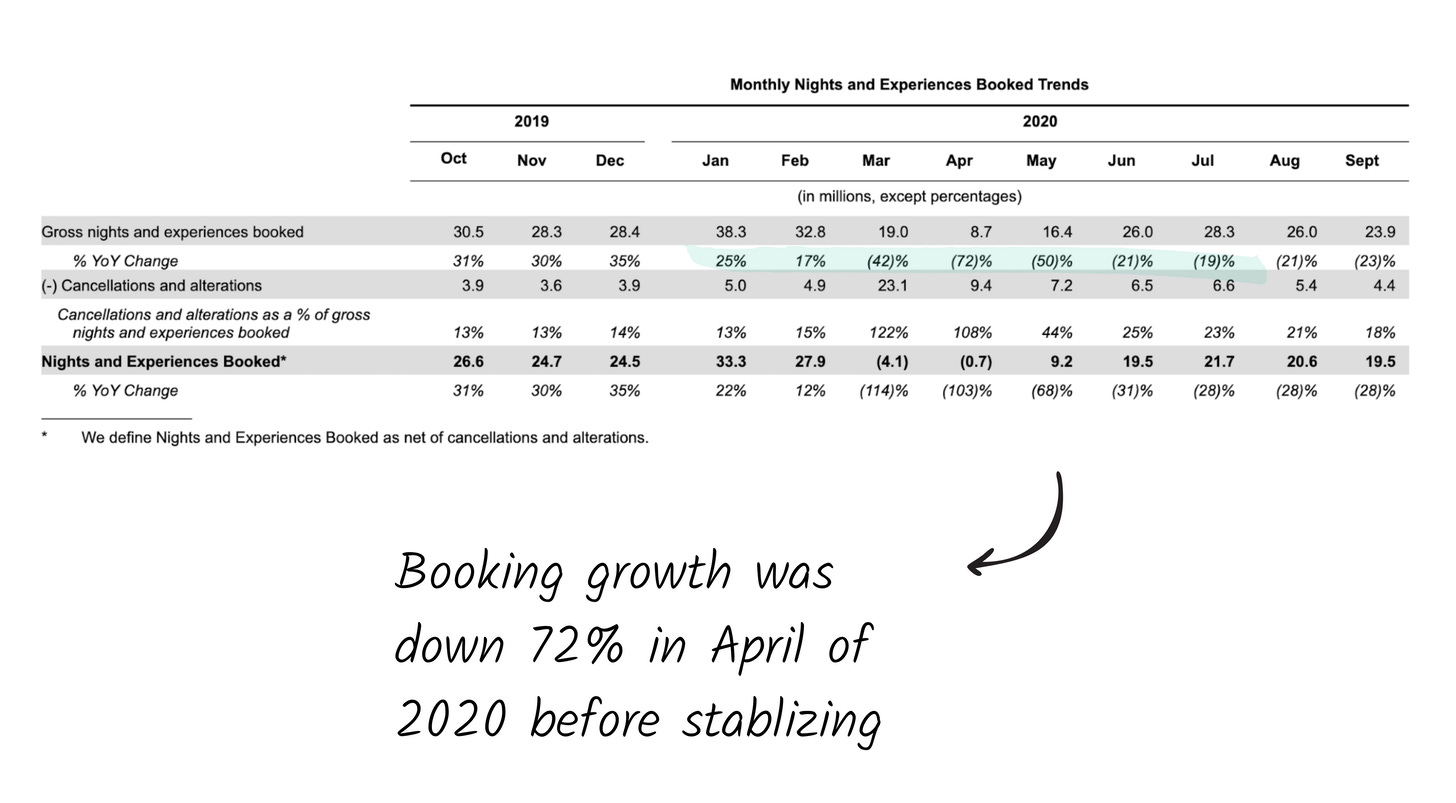

When viewed through this lens, Airbnb's 2020 feels less like an out-of-left-field catastrophe and more like a returning leitmotif of endurance through disaster. In April, Airbnb's booking growth — one barometer of health — declined 72% from the year prior. Revenue was down 32% year over year through September of 2020.

Yet, Airbnb is still here, heading to IPO nearly a year later than Chesky and Gebbia had hoped. Short-term, investor interest may inversely correlate with a fear index — if positive vaccine trials are a mirage and borders remain closed, Airbnb's 2021 may look bleak. But those either with a rosier view of the next twelve months or a longer time horizon may wish to ask different questions.

Namely, how can Airbnb stay one step ahead? The company will need to outfox competition, as hospitality incumbents shoulder into the sharing economy, and regulators, content to gum up the gears in specific geographies. Moreover, they'll need to do so while navigating towards profitability, a prize that has mostly eluded them thus far.

Number of mentions in the S-1

COVID-19: 215

Connection: 203

Belonging: 45

Brian Chesky: 126

Joe Gebbia: 60

Airbnb Experiences: 15

Resilience: 12

Airbnb history

Successful companies often look preordained, post-hoc. That's not the case here.

When Brian Chesky, Joe Gebbia, and Nathan Blecharczyk launched airbedandbreakfast.com thirteen years ago, no one, not even the founders, realized they were building a company that would go public.

Brian Chesky and Joe Gebbia, two Rhode Island School of Design (RISD) grads, launched "AirBed & Breakfast" with humble ambitions. When the Industrial Designers Society of America (IDSA) conference came to San Francisco in 2007, overwhelming the city's hotels, Joe emailed Brian with an idea to "make a few bucks." He thought it would be a crafty way to subsidize their rent.

Brian and Joe presumably didn't anticipate that renting out air mattresses in their apartment would become an IPO-worthy business, or they wouldn't have offered guests a gift bag that included "change for bums." But it was San Francisco, and from the earliest days, the duo wanted guests to "live like a local."

Cringey gift bags aside, the plan worked. Three people stayed with them during the conference, helping cover rent and leading to real friendships. One of the original guests even invited Chesky to his wedding.

That weekend's success gave Brian and Joe the confidence to recruit an old roommate, Nathan Blecharczyk, to join them in turning their experiment into a business. It didn't last long. Soon after they started working together, the trio ditched their idea.

"It's funny but we didn't think Air bed and breakfast would be a big idea," Chesky told Reid Hoffman, "We thought it might be able to pay the rent until we could think of the big idea."

Ironically, Airbnb's founders viewed the company the same way hundreds of thousands of hosts would over the next decade: as an easy way to make extra money from extra space, not a huge business. Instead, they built a roommate matching service, getting four months in before they realized Roommates.com was already a thing. Airbnb was back on.

Airbnb relaunched, limited to serving visitors looking for air mattresses during conferences. Few cared. After reopening for business at SXSW in 2008, two people booked. One of them was Chesky.

It was time to relax the restrictions and open up the platform to people that wanted real beds, anywhere, at any time. In driving toward that vision, the team made three product decisions that shaped their future:

Facilitating payments on-platform. Instead of sending guests to PayPal or another website, Airbnb handled payments themselves. In 2008, pre-Stripe, this was not an obvious call.

Introducing ratings. Airbnb introduced a reputational system in which hosts and guests rated each other. Contrast this with hotels, which are reviewed by external search engines. By hosting this on the platform, Airbnb integrated trust and reservations into their system.

Three-click booking. Drawing inspiration from Steve Jobs and the iPod, the Airbnb team built the product to work with minimal friction. In just three clicks, anyone could book a place to stay. If this seems obvious today, that's because Airbnb did it.

With the product built and confidence high, the founders went out to raise a seed round. The deck they went out with is available online, and once again highlights the stark contrast between Airbnb then and now.

Raising wasn’t easy, as Chesky recounted:

[W]e were introduced to 15 angel investors — we were trying to raise $150K at a $1.5M valuation. Seven investors never responded, 8 replied — of those 4 said no "it didn't fit within their thesis," 1 said they didn't like the market, and 3 just passed.

With no funding and a baseball card binder full of maxed-out credit cards, the team decided to launch once again, this time around the 2008 Democratic National Convention in Denver. They sold 80 rooms but knew that after the DNC, they would find themselves in the same position: customerless and debt. If the "AirBed" in AirBed & Breakfast wasn't working out, they thought maybe the "Breakfast" would.

Designers by training, Chesky and Gebbia created and produced limited edition Cap'n McCain's and Obama O's cereals that they sold for $40 a pop. That hack netted the company $30K, keeping the lights on.

As it turned out, the stunt had broader implications. For one thing, it impressed Y Combinator (YC) founder Paul Graham, who reasoned, "If you can convince people to buy cereal, you might be able to convince people to rent air beds." Referencing their indestructibility, Graham called Airbnb "the cockroach of startups," a compliment in startup-speak but not the best marketing copy for a hospitality company. The famed incubator accepted Airbnb into their cohort and invested.

It was the break the young, struggling company needed. YC gave them legitimacy, permission to focus full-time on the business, and critical advice: do things that don't scale. The team took that to heart. Two examples:

Airbnb hired professional photographers to shoot pictures of every listing in NYC to make them more appealing to guests.

Chesky personally traveled city to city and stayed in Airbnb listings to better understand the product and experience.

YC was also when the company changed its name from the clunky and limiting "AirBed & Breakfast" to the smooth, short, and versatile "Airbnb" millions know and love today.

The name change and the hard, unscalable work began to pay off. After those initial fifteen rejections, Airbnb convinced Silicon Valley's pre-eminent venture capital firm, Sequoia Capital, to lead its $600k Seed Round in April 2009. Later funding was fast and furious. Over the past decade, Airbnb has raised $4.4 billion in equity financing from a who's who of venture capital and private equity firms..

Airbnb's growth took off, too. By 2011, Airbnb users had booked a million nights (or 2,739 years) through the platform. With great scale came great responsibility. That year, Airbnb was dealt its first major crisis when a guest trashed a host's apartment, setting off safety concerns. The company responded by offering to cover the costs and provide housing to the host while her home was repaired. It later instituted a policy to cover guest damages up to $1 million.

Fun fact: that same year, within a week of each other, Airbnb made its first acquisition — German Airbnb clone, Accoleo — and closed an investment from Ashton Kutcher. The actor and VC became a "strategic brand advisor" for the company.

By January 2012, Airbnb hit 5 million cumulative nights booked. Just six months later, in June 2012, the company hit 10 million. As Airbnb grew, its platform and userbase evolved. Professional hosts emerged, making a living from managing multiple listings over extended periods. Though beneficial to the platform, professionalization attracted negative attention from some cities. New York, San Francisco, Barcelona, and others have fought Airbnb tooth-and-nail over short-term subleasing, arguing that they drive up real estate prices and steal tax revenue from hotels. Many such battles are ongoing.

Despite regulatory headwinds, demand continued to snowball. With confidence in the core business, Airbnb began expanding beyond its core product. It's two biggest bets are Experiences and Backyard.

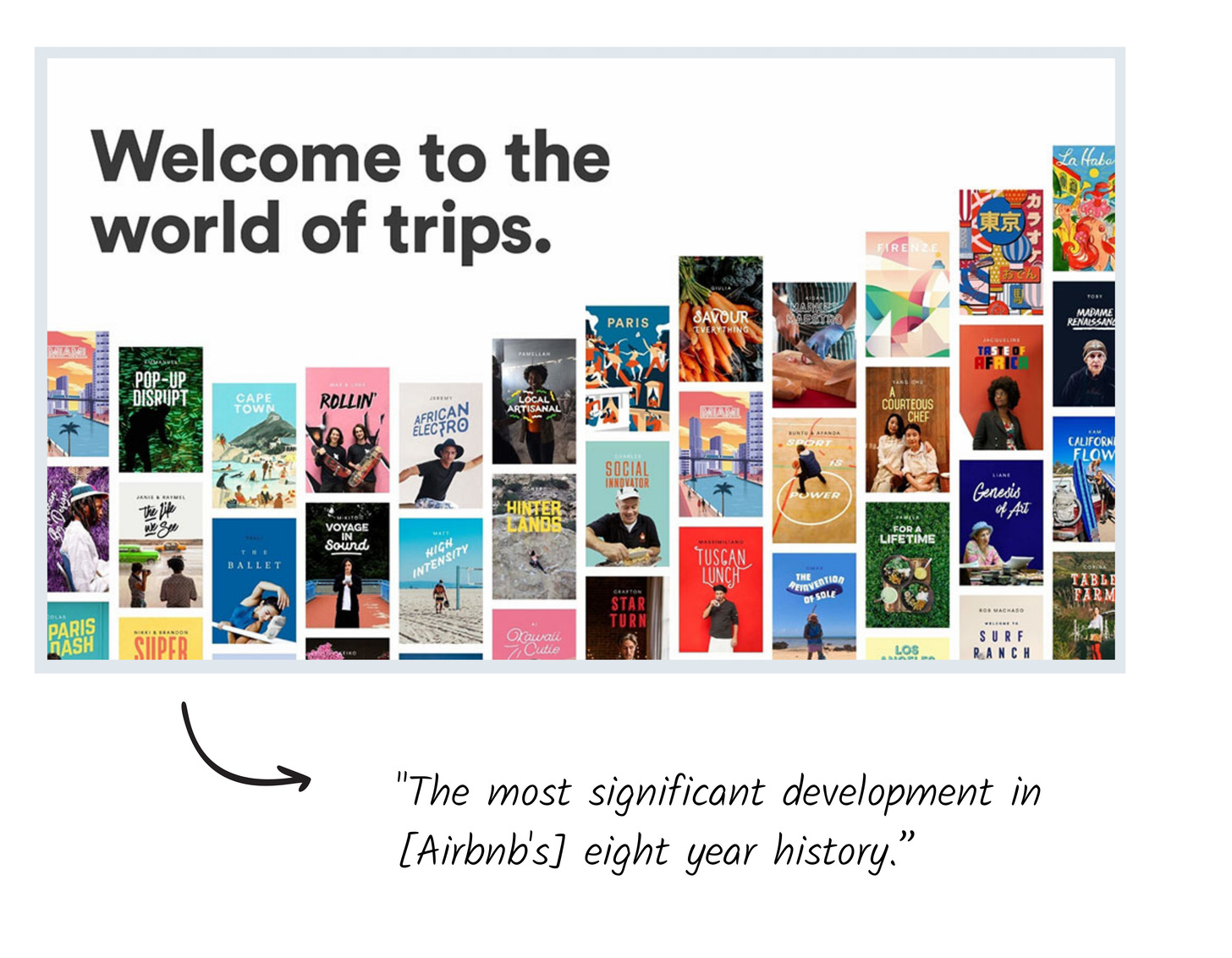

In November 2016, Airbnb launched Experiences, beneath the umbrella of Trips, which it called "the most significant development in its eight-year history."

Trips was intended to serve as a centralized platform to manage travel from start to finish, including securing flights. At the time of launch, Trips provided access to special guidebooks, and bookable Experiences, like learning to make a violin in Paris. To date, Experiences have yet to live up to Chesky's vision as equally important as accommodations.

Another of Airbnb's ancillary bets was revealed in November 2018. The company's experimental product development team, Samara, unveiled plans for Backyard. With Backyard, Airbnb plans to design and build housing units, using its data on where and how guests like to inform design and placement. The same week Airbnb announced Backyard, it quietly filed a patent for a reusable modular housing system. That hints at a fascinating future: Airbnb homes that can adjust their layouts to meet demand in real-time. The same space could be rented as two one-bedroom units one week and a two-bedroom apartment the next, multiplying the available housing combinations without altering the footprint. There's been no visible movement on the project since.

Other moonshots have been paused in response to the coronavirus, which forced Airbnb to focus on its core business. In a July interview, Chesky gave a brief status update on Airbnb's experimental bets. Emphasis ours.

We had a really awesome transportation product and I felt like if next year you were going to book a flight, I think it would've been pretty awesome on Airbnb. We've paused that entire project. We're not offering that for the foreseeable future. We had a whole content play, travel content, we paused that. We took our hotel business... that's still important but we had to scale it back. Airbnb Plus, it's a mid-tiered product, we had to basically scale that back. Our luxury product, we had to scale that back. And a few other things. So we basically took anything that wasn't the core of community that was all about connection, anything that was further out from that nucleus, those we had to reduce.

The "connected trip" where a single platform handles A through Z of travel continues to be a dream for Airbnb and incumbent Online Travel Agencies (OTAs), but it will have to wait. Both Experiences and Backyard have survived for the time being, with Experiences offering its events online. Investors may wish to keep a close eye on both projects, as they inform how effectively the company can monetize beyond bookings and how soon it might resurrect other experiments.

The coronavirus outbreak has not only altered parts of the product but consumer behavior. Guests have shifted from booking short-term stays in populous cities to longer-term stays in remote locations. More than ever, Airbnb is blurring the lines between the travel and housing markets. That might spark more regulatory concern but could expand the company's addressable market massively, reaching multiple trillions.

Though 2020 has inevitably been tough, there's plenty of reason for optimism. The cockroach survives.

Market

So, onto that gargantuan market.

One of the most shocking numbers in the entire S-1 document is the following: $3.4 trillion. That's the company's estimate for their total addressable market (TAM). It is staggeringly large. To put it in context, Airbnb's estimated TAM is ~42x larger than Snowflake's, the last blockbuster IPO of 2020. While they're radically different businesses, of course, a comparison nevertheless provides a sense of scale.

The reason Airbnb's opportunity is so enormous is partially because it created a new category. While the company describes its market as simply "the growing travel market and experience economy," that underplays Airbnb's effect on the industry. By building trust into the platform, Airbnb normalized the renting out of spare rooms or empty homes. The result was an enormous influx of new supply, without the capital requirements. Guests that might not have been served by the old model were welcomed into this new category of hospitality. This is to say that not only has Airbnb changed the travel industry, it's expanded the market in the process.

Airbnb breaks down its opportunity into two components: the serviceable addressable market (SAM), and the TAM, as mentioned. The company has used 2019 market data to calculate the size of these opportunities, as it believes this represents a more accurate depiction of the sector and its implied growth. That makes sense given the effect of covid-19, but by definition, doesn't account for any permanent changes in consumer travel behavior wrought by the virus. We can understand how Airbnb sees the market evolving by identifying the space between the two.

The listed SAM is straightforward. Eighty percent consists of Airbnb's core business, "short-term stays," defined as those lasting 28 days or less. The remaining 20% comes from Experiences paid for by tourists participating in those short-term stays. For the sake of conservatism, Airbnb has purposely excluded stays surpassing 28 days, a significant omission given that "long-term stays" represent 24% of bookings for the year-to-date (YTD) period ending September 30, 2020.

Reviewing Airbnb's TAM, we're able to find meaningful adjustments that illuminate the company's assumptions about the sector:

Expanding short-term stays. Airbnb expects an expansion in the short-term market from $1.2 trillion to $1.8 trillion. This growth is based on an increasing population and a growing travel market — the company estimates trips per capita will increase from 0.84x to 1.11x by 2030. Airbnb expects to contribute to market expansion by encouraging travel that would not have otherwise occurred.

Opening up long-term stays. Airbnb believes that, by continuing to grow its global community of hosts, it can tap into around 10% of the residential real estate market, totaling $210 billion.

Expanding Experiences. Will Airbnb become the first port-of-call for those looking to entertain themselves closer to home? The company believes so, betting on expanding the experience market opportunity from $239 billion to $1.4 trillion. This is driven by enlarging the customer set to incorporate local communities pursuing recreational and cultural attractions, including sporting events, amusement parks, summer camps, and more.

In summary, Airbnb is betting on two significant developments. First, consumers will increasingly look for extended stays, equivalent to a sublease rather than just a week or two of vacation. Second, locals (read: not tourists) will turn to the platform to explore their city, and that they'll do so in that rival Airbnb's OG business.

There's a degree of tension suggested by these two assumptions. While Airbnb uses 2019 figures to aid its SAM and TAM calculations, arguing that pre-coronavirus figures are most representative of travel's present and future, these surmisals suggest a different conclusion. The pandemic has increased the average length of stay and the number of local trips, a reasonable proxy for engaging in local experiences. In this respect, Airbnb seems to want it both ways: maintain the travel industry's pre-coronavirus size and growth, and add consumer preferences for extended stays and provincial spending.

The final item of note concerning Airbnb's market opportunity is its geographic diversity. Of the $3.4T TAM:

$1.5 trillion is in Asia Pac (44%)

$1.0 trillion is in EMEA (29%)

$0.7 trillion is in North America (20%)

$0.2 trillion in Latin America (5%)

Airbnb has managed to expand its global footprint both through M&A and in-house efforts. As detailed by Skift, China and India represent focus markets for the company. Both were growing rapidly before the pandemic. If Airbnb is to succeed in taking over the globe, it will need to refine its new market strategy given most opportunity exists outside of the US.

Product

At its core, Airbnb is a marketplace that offers two travel-related products, Stays and Experiences. That marketplace facilitates the connection of the buyers ("guests") and the suppliers ("hosts") of those products.

Stays is the product you think of first when contemplating Airbnb's product. It provides access to overnight accommodations offered by hosts.

Experiences, as we discussed, are activities guests book, the content of which varies widely. Traditional tourist activities like a guided walking tour sit alongside psychic readings, glamorous photoshoots, and pasta-making classes.

Airbnb's products are best described in the context of the two stakeholders, guests and hosts, since the end product is quite different through the lens of each. We'll dig into both before providing a case study of a professional host.

Guests

For guests, Airbnb's product is a platform to find, vet, and book stays and experiences. Broadly speaking, the platform facilitates three actions: searching, pre-vetting, and executing.

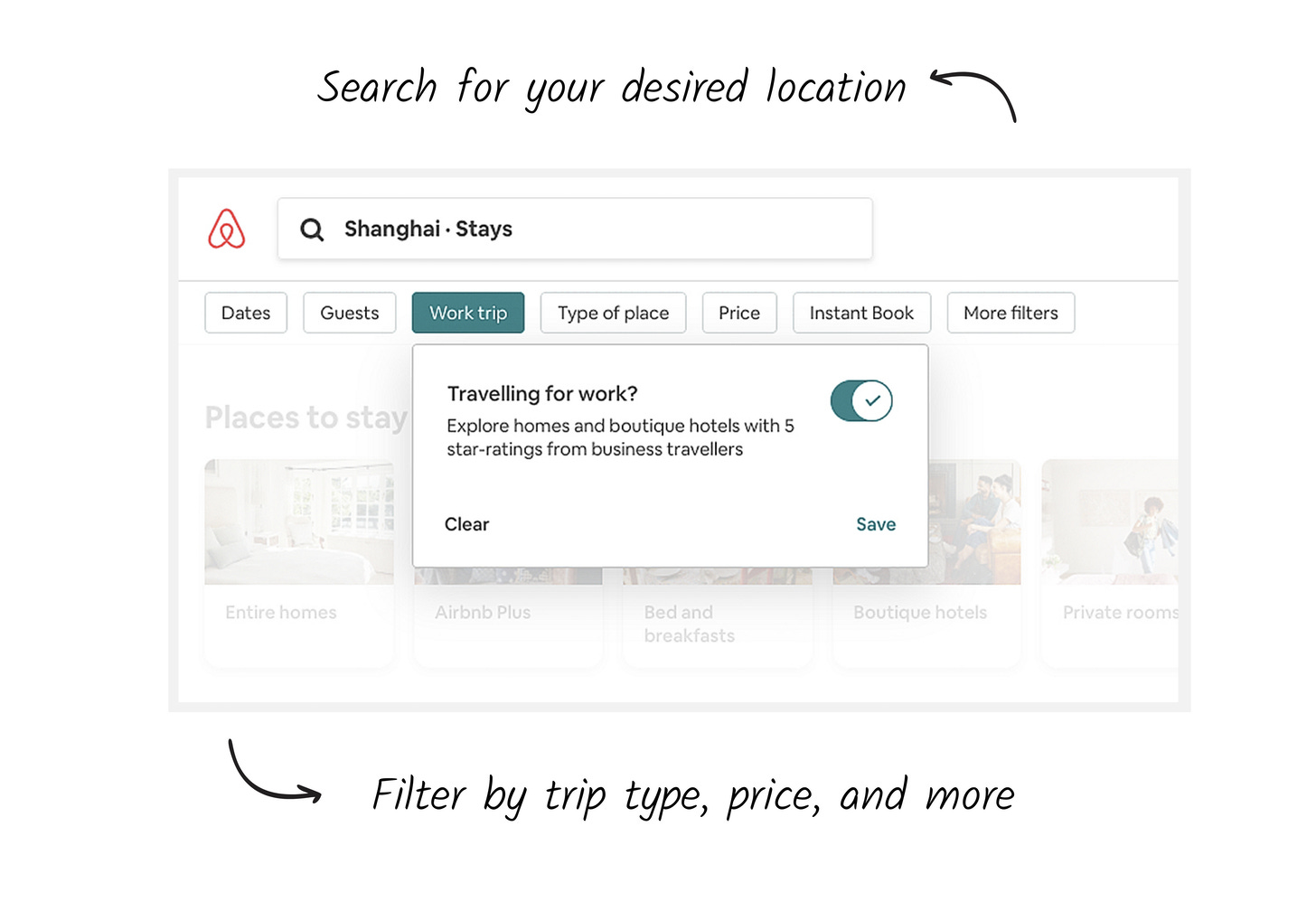

Searching

Within the platform, guests can search for stays and experiences by location. Airbnb's search functionality allows for filtering by specific criteria: neighborhood, price, number of guests, amenities, and so on.

This is the traditional two-sided marketplace approach — connecting buyers and sellers through search functionality. Beyond its intuitive design, there's nothing visibly revolutionary about the Airbnb interface, though obviously, the underlying inventory accessed is a product of the company's innovation. It's really in vetting and booking that Airbnb differentiates itself from traditional marketplaces.

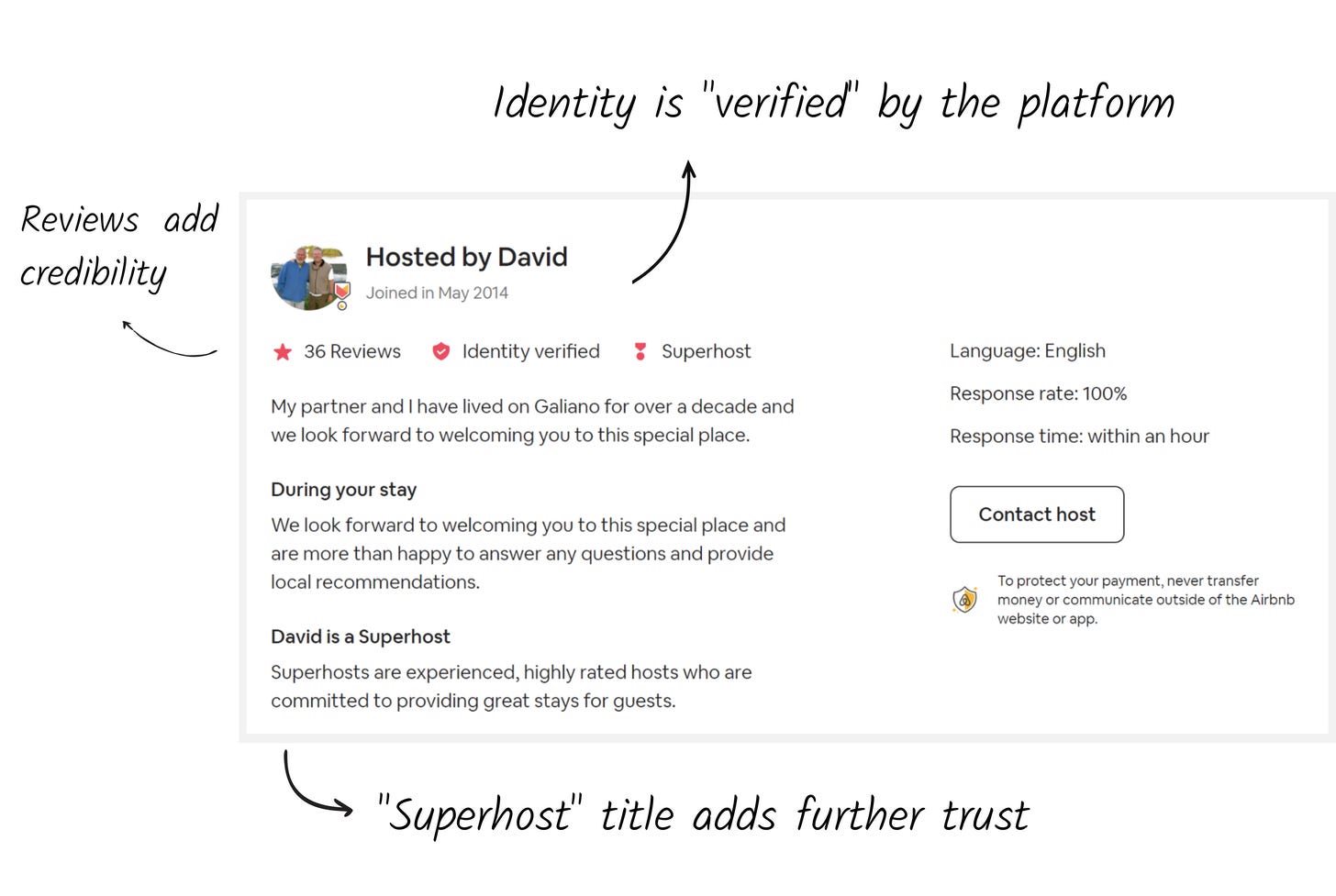

Vetting

Airbnb allows guests to vet their stay or experience in advance. Removing the need for back-and-forth communication with the host, Airbnb's postings are designed so answer guest questions upfront:

Is this host trustworthy? Has the platform verified their identity?

Have other guests visited? What did they think of the place?

What amenities does this place offer (Wifi, hairdryer, workspace)?

In short, Airbnb's product pre-emptively addresses a buyer's concern, a sharp departure from traditional marketplaces like Craigslist.

It's in no small part down to these details that, today, staying in a stranger's home sounds safe, reasonable, and even desirable.

Booking

Once a guest has found a stay or experience they like, the Airbnb platform helps them book and pay.

You can imagine what transactions might look like in the absence of Airbnb: a nightmarish web of back-and-forth emails, international money transfers, and check-in logistics. Airbnb codifies all of this along with collecting two-sided post-trip reviews. The result is an increasingly trustworthy platform and a seamless experience for guests.

Hosts

Though stakeholders benefit from shared functionality, hosts interface with the Airbnb product through a different lens. The three primary focuses of the product are onboarding, management, and monetization.

Onboarding

To continue increasing its supply, Airbnb puts great effort into making it easy to get up and running as a new host. This includes providing insurance and protection, minimizing the downside of hosting, guidance on pricing and listing, and a 24/7 customer support team. The company's "Ambassador Program" pairs Superhosts with ingenues as a way to provide community support to those just getting started.

Management

Once onboarded, Airbnb's suite seeks to simplify reservation management. This is done by providing guest messaging, scheduling, and merchandising features. The goal is to streamline the process and provide near-professional level tooling for serious hosts.

Monetization

Beyond collecting payments, Airbnb looks to make hosts financially successful. Hosts can track earnings through the product. Personalized insights are provided based on travel trends, designed to produce higher earnings and better reviews. Experiences offer an ancillary revenue stream, allowing hosts to earn outside of renting their home or as a way to build the bill.

Case study: A professional host

There is no "typical" background for an Airbnb host, but they do fall into two clear categories: dabblers and professionals. Dabblers are those for whom Airbnb represents a side-hustle, a fun way to make some extra cash. Professionals run full-time businesses through the platform, typically operating multiple properties. The relative size of those groups is not disclosed in the S-1. Airbnb's site does have a specific page for those that make their living managing a string of listings, suggesting professionals make up a significant portion of the hosting base.

As Airbnb grows, the opportunity to build a meaningful business on top of the company's platform increases. With that in mind, we consulted a professional host to understand their journey, toolset, and experience with Airbnb.

Let's call our professional "Sylvia."

Sylvia got started hosting when she noticed a potential arbitrage. There was a great deal of apartment stock available on the Peninsula south of San Francisco but few hotels. The available hotel units were low-quality but highly-priced, charging $500 a night or more, even mid-week. Sylvia recognized the imbalance between apartment and hotel supply as an opportunity and turned to Airbnb to capitalize.

First, Sylvia compiled data on apartment vacancies and rental prices, using information available on the Multiple Listing Service (MLS). Sylvia then used AirDNA, a short-term rental intelligence platform, to gather Airbnb nightly rate and demand data. Comparing the datasets, Sylvia identified geographic pockets where the arbitrage was most pronounced, warranting the establishment of a property management business.

Once recognized, Sylvia set about amassing available units. She did this by approaching building managers on the Peninsula and offering to lease all vacant units at a discount. This was a no-brainer for many managers and capital partners, allowing them to hit occupancy rates defined in loan covenants. Setting up a standard two-bedroom unit took approximately two days and an $8K investment. While units typically rented for $3-4K a month, Sylvia could earn $200 - $400 a night, maintaining an 80% occupancy rate. That means Sylvia brought in as much as $9.6K per unit with a gross profit of $6.6K, even if you assume she received no discount on the unit cost.

At its peak, Sylvia's company employed three full-time staff members and managed 20 units on the Peninsula. If we imagine our back-of-the-envelope math to be reasonable, Sylvia's company was brought in close to $200K a month with a gross profit of $132K. It's worth noting that some hosts manage 100, 500, or over 1K units. Sonder, a venture-backed "competitor," which focuses on higher-end properties, is the largest host on Airbnb, managing 3.5K listings as of 2019. Before shutting down, Lyric, a similar business that raised money from Airbnb, also used the platform to expand its footprint.

At scale, professional hosts often turn to tools beyond the Airbnb platform. Beyond Pricing and Wheelhouse optimize nightly rates, while Guesty manages bookings across platforms including Airbnb, Booking.com, and Vrbo. This represents a notable development in Airbnb's market — as competition has increased, professional hosts now promote listings on several marketplaces. For reference, Sylvia received approximately 65% of their bookings through Airbnb, 30% through Booking.com, and the rest through VRBO and other listing sites.

We should expect other products to emerge, built for professional hosts like Sylvia. While Airbnb is considered the best "host-friendly" product per our sources, one commonly-cited area for improvement is the claims product. It remains difficult for hosts to recoup payment for damages incurred by a guest. Perhaps, we'll see a startup emerge to serve this use-case.

Business model

You can't fault Airbnb's concision when discussing their diversity of revenue. The S-1 filing lists just one source: service fees.

That's it, nothing more.

It's an intriguing line in so much as it highlights all the ways Airbnb has chosen not to make money. One might imagine the company taking a cut of payments, raking in cancellation or cleaning fees, or charging for early check-ins or late check-outs. A more rapacious business might nickel-and-dime consumers throughout the platform lifecycle. Airbnb has taken a different approach, clearly deciding to keep the business model simple and remove negative incentives to take business off-platform.

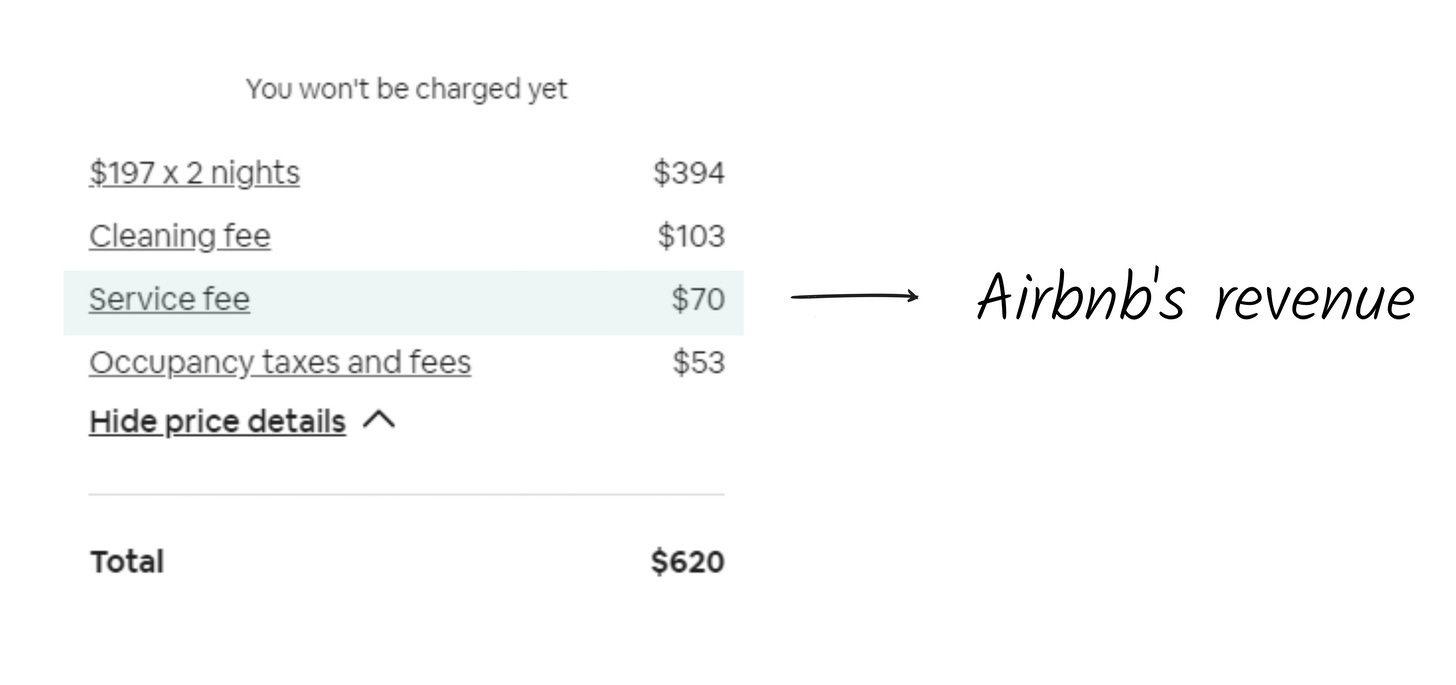

Airbnb levies its service fee on both hosts and guests, calculated as a percent of the booking value. If you've been an Airbnb guest in the past, you may recognize it from the price breakdown:

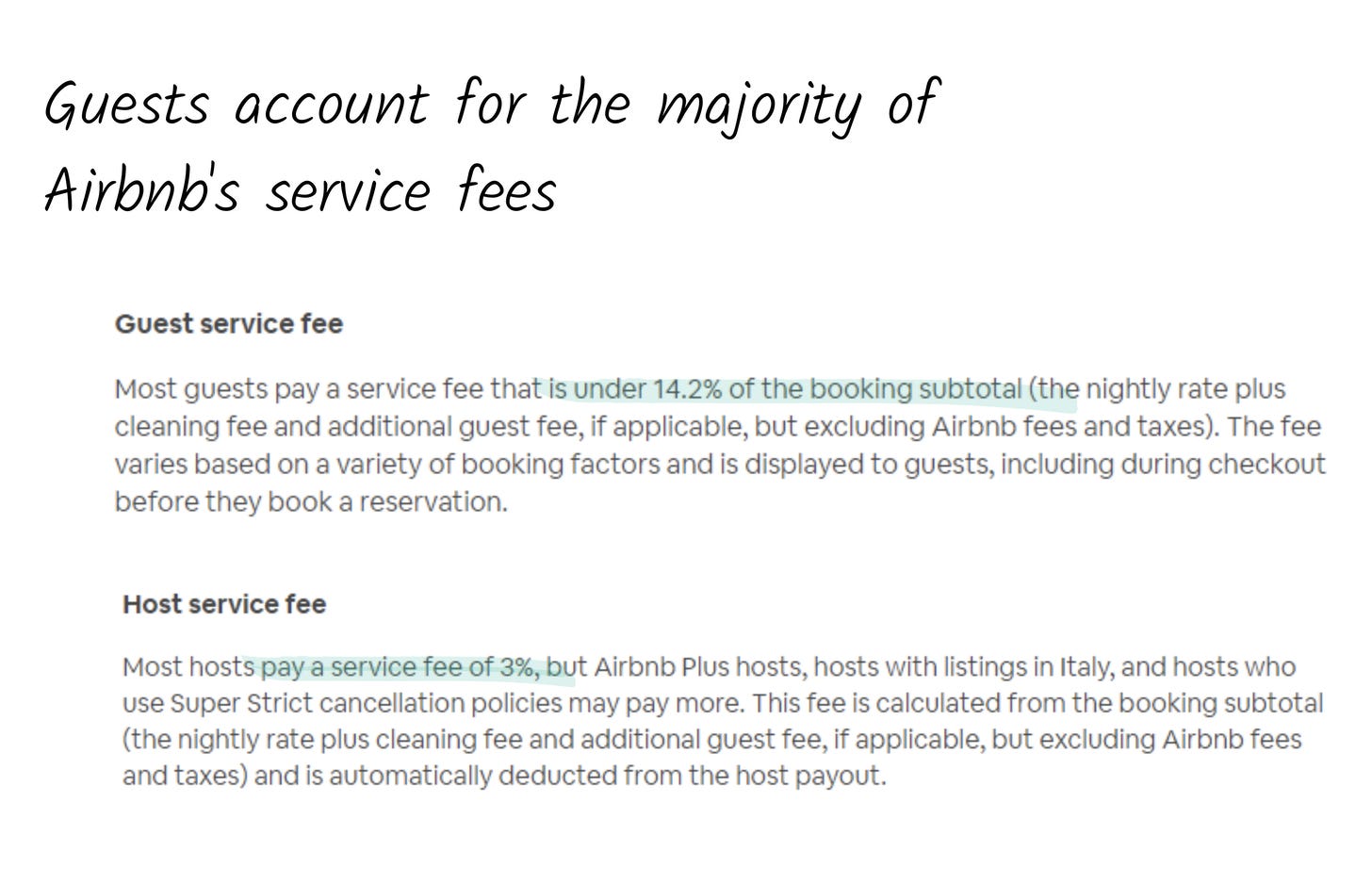

In 2019, Airbnb raked in $5.3 billion in service fees on a Gross Booking Value of $38.0 billion - so its service fees accounted for 17% of GBV. That 17% cost is shared, though not equally, by the guests and the hosts.

As made clear in Airbnb's policies, the bulk of the fees fall on the guest, with "most guests" paying under 14.2%, and "most hosts" paying 3%.

These service fees cover "certain activities, including use of the Company's platform, customer support, and payment processing activities."

For all the simplicity of the model, Airbnb doesn't share exactly how it calculates its fees. The S-1 notes that "service fees vary based on factors specific to the booking, such as duration, geography, and host type," but doesn't elaborate further.

Airbnb monetizes Experiences slightly differently. The platform does not charge guests and instead charges hosts a flat 20% fee. Over time, as the company better understands this product's dynamics, we might expect a dynamic fee structure that allows Airbnb to capture more upside.

All in all, Airbnb exhibits one of the simplest business models you'll come across for a company of its size. It will be interesting to see whether this evolves as Airbnb enters public life and potentially expands its product suite.

Management

As you might have gleaned from the "Airbnb History" section, co-founders Brian Chesky, Joe Gebbia, and Nate Blecharczyk were not seasoned operators. All three were first-time entrepreneurs, with the exception of Gebbia's undergrad dalliance with Critbuns, a soft foam cushion designed to protect one's tailbone during prolonged sittings.

As mentioned, Chesky and Gebbia were designers by training, having graduated from RISD, while Blecharczyk studied computer science at Harvard.

The importance of design is imprinted on the business. From the beginning, Chesky and Gebbia viewed business problems as a series of design challenges. When their landlord increased rent by 25%, their response was to ask, "how can we design our way out of this?" The answer involved three air beds and is covered in detail above. An even bigger design problem was giving guests the comfort to stay in a stranger's home. Here the solution relied upon crafting trust through profiles, two-way reviews, messaging, and payments.

This human-centered design remains key to management's approach. In a 2018 podcast, Chesky said:

Algorithms are really good at optimizing one or two metrics. If you're trying to balance between multiple stakeholders, you'll need a lot of human intervention.

The company's response to Covid-19 illustrates this conscientiousness with which Airbnb treats its stakeholders. While revenue nose-dived and hundreds of millions worth of expenses were cut, Airbnb set aside a $250 million relief fund for hosts. When approximately 1.8K employees were laid off in May 2020, the company provided generous severance, job search support, and one-to-one conversations between senior leaders and affected staff. Layoffs are always grisly affairs, but management worked to soften the blow.

Outside of the coronavirus crisis, Airbnb has demonstrated an unusual thoughtfulness. Rather than seeking to bulldoze local governments, Airbnb has worked with these localities on issues like collecting hotel taxes. This represents a sharp departure from the confrontational playbooks of other sharing economy businesses like Uber.

Beyond its founding trio, Airbnb's leadership is staffed with experienced tech and hospitality operators. Before joining Airbnb, CFO Dave Stephenson spent 17 years at Amazon, including stints as CFO for their Worldwide Consumer Organization and International Consumer Organization. Stephenson should provide sturdy financial guardrails, and given Amazon's track record of making long-term, positive ROI investments (RIP Fire Phone) should help guide strategic acquisitions and internal investments.

CTO Aristotle Balogh spent a decade between Google and Yahoo. At Google, he helped build the infrastructure and data platforms behind Google Search, particularly relevant given the centrality of search to Airbnb's product. Given the scale of Google's tech infrastructure, Balogh should be equipped to ensure Airbnb's platform capabilities exceed its growth.

Finally, Global Head of Hosting Catherine Powell spent 15 years at Disney before joining Airbnb, amassing extensive parks experience, including overseeing Walt Disney World in Orlando and Disneyland Paris. It's intriguing to contemplate how Powell's bonafides might come into play should Airbnb execute on Backyard and more directly integrate Experiences with managed physical assets. Experiences are explicitly part of Powell's mandate, and The Mouse House is best-in-class at creating magical experiences (and emptying wallets).

Investors

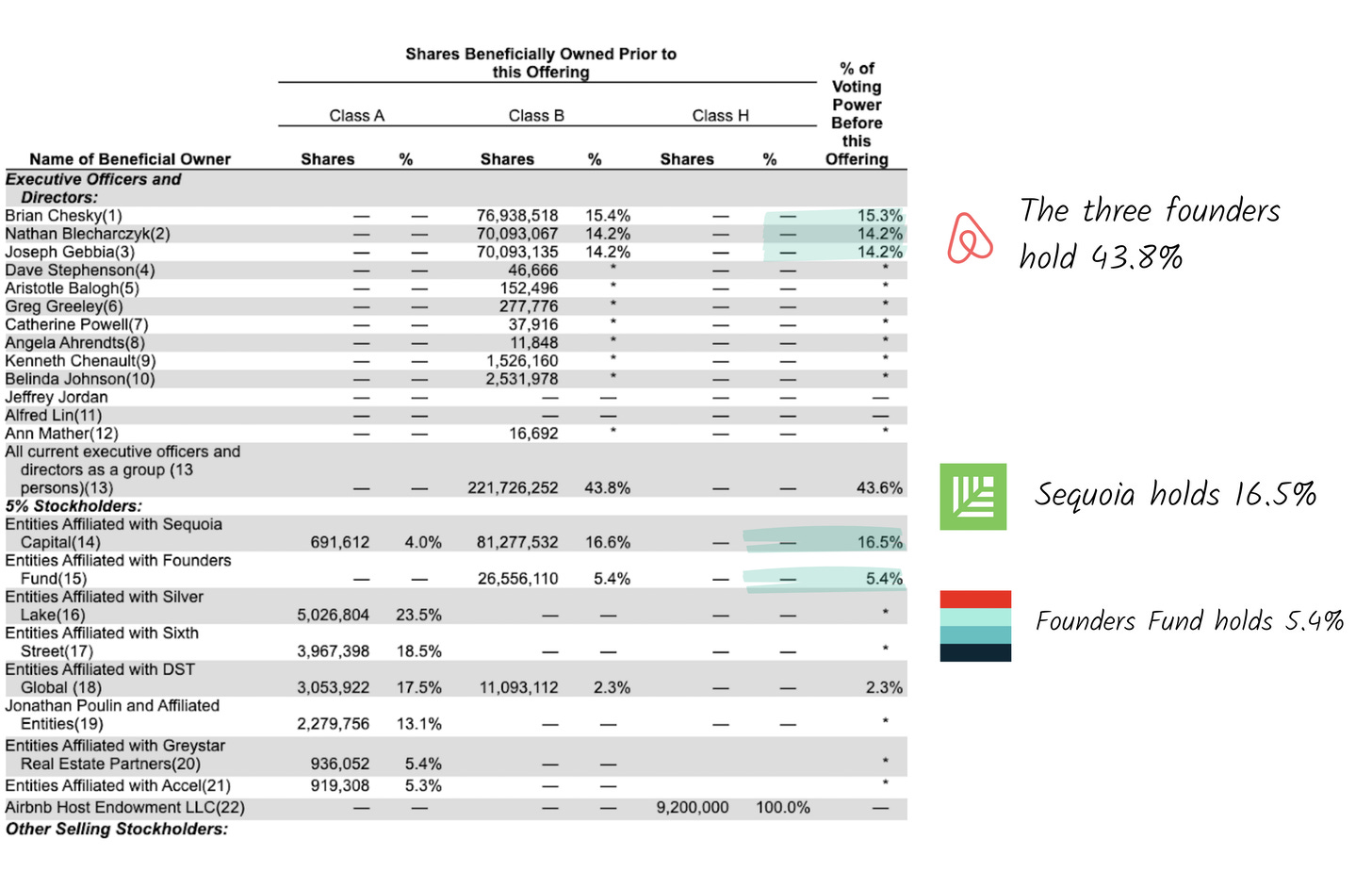

There are several notable investors on the cap table, but the firm that's been there the longest is Sequoia Capital. A veritable venture stalwart, Sequoia first got involved in 2009 when the only employees were the three co-founders. At the time, Airbnb had just 1K listings, a far cry from the 7.4 million touted in the S-1. Owning 16.5% of the Class B shares, they are positioned to take home ~$5 billion at the rumored $30 billion valuation. Founders Fund, another high-profile Silicon Valley firm, holds 5.4% of the pool, worth $1.62 billion on the same terms. It's worth noting that Class B shareholders, which include the three founders, possess twenty times the voting power of those with Class A positions.

Silver Lake and Sixth Street are among those in the latter camp. The two firms have had the shortest stint on the cap table, having ponied $2 billion in debt and equity financing this April. When nobody wanted to touch anything related to travel, these firms pinched their noses and made what will turn out to be an exceptional trade. The investment's cost basis is said to be ~$18 billion, nearly half the IPO valuation. And while it's worth noting that an investment in the NASDAQ at the same time would have had similar returns, the chutzpah required to deploy that capital in those market conditions is commendable.

The IPO

There's some irony that, during a year synonymous with stay-at-home orders, a travel company is one of the most highly anticipated IPO of the last twelve months.

That's due in no small part to the strength and reach of Airbnb's global brand. Whenever a consumer-facing business like Airbnb progresses to the public stage — especially one that millions of Americans regularly interact with — it tends to make a bigger splash than enterprise counterparts, at least on Main Street. Airbnb's position as a gritty underdog doesn't hurt, either. It's hard to root against a company that has taken quite so many licks over the past few months and seemingly emerged emboldened.

One other detail worth mentioning: as recently as mid-November, Airbnb was said to be considering a dual listing on the Long-Term Stock Exchange ("LTSE") in addition to its traditional IPO. The LTSE is a new exchange backed by a16z, Founders Fund, and others, that seeks to encourage companies to consider ESG and diversity initiatives. Signing Airbnb would represent quite a coup for LTSE, which received SEC approval in 2019.

A final decision hasn't been made and likely won't be until late 2020 or early 2021, but it wouldn't be a surprise if it went through. Airbnb has demonstrated an interest in inclusive, responsible corporate governance over the past few years, particularly since this open letter in 2018. Adhering to LTSE's standards feels in line with management's values and contributes to Airbnb's public image.

Financial highlights

As one would expect, 2020 took some of the *air* out of this business (Ed: we're very sorry), given the material travel disruptions caused by the coronavirus. Despite the downtick, Airbnb has meaningfully outperformed other travel businesses experiencing the same headwinds. Management quickly recognized the pressures faced and took decisive steps by raising debt and cutting headcount, executive salaries, and marketing spend. This state of flux makes deciphering Airbnb's financials particularly challenging.

The company measures financial performance across a few key metrics. Given the potential for confusion, we believe two are particularly worth defining.

Gross Booking Value (GBV). This is defined as the dollar value of bookings on the platform, including host earnings, service fees, cleaning fees, and taxes, net of cancellations and alterations. In many ways, GBV can be thought of as "gross revenue."

Revenue. This represents the amount brought in by Airbnb through service fees. In this respect, it may be better viewed as "net revenue."

A high-level look at the company's financials portrays a picture of growth and progress, interrupted.

In terms of GBV, the company generated $38 billion in 2019, supporting a growth rate of 29% from $29 billion in 2018. These GBV metrics equate to Revenue of $4.8 billion and $3.7 billion in 2019 and 2018, respectively. The first three quarters of 2020 saw both metrics take a hit, with Airbnb generating just $18 billion in GBV (down 39% YoY) and Revenue of $2.5 billion (down 32% YoY).

The coronavirus impacted Airbnb's margin profile, too. Operating margins dropped from -4.7% for the first nine months of 2019 to -19.5% over the same period in 2020, a compression of ~15%. This indicates that even after cost-cutting, there's a decent amount of operating leverage in the business.

To wit, the financials for Airbnb are a mixed bag: some good, some bad, and plenty of unknowns. We'll dig in below.

The good

There's reason for optimism. Airbnb's good work over the last thirteen years has not been wiped out by covid-19, with the platform's enduring power demonstrated by robust acquisition, growth, and retention figures.

Despite slashing Sales & Marketing (S&M) spend by over 50%, from $1.2 billion over the first nine months of 2019 to $546 million over the same period in 2020, Airbnb's acquisition remained strong. Impressively, 91% of all traffic to the site came through direct or unpaid channels, supporting an organic growth story. When it is time to travel (or find a new experience), a large portion of guests instinctively navigates to Airbnb.

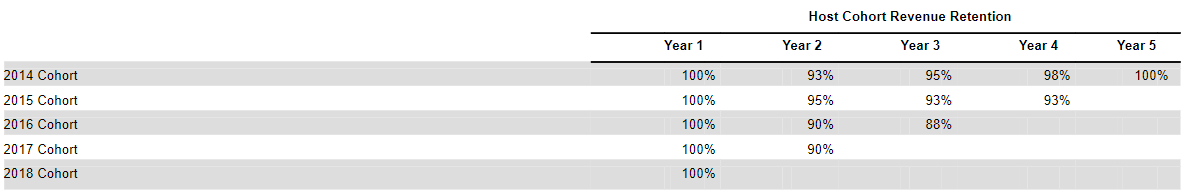

On the other side of the coin, host loyalty is best understood through retention data. As outlined below, Airbnb's host revenue retention since 2014 sits at or above 88% by cohort. This underscores the company's attractive positioning on the supply side and ability to drive operating leverage over time.

So, how does Airbnb's strength on both the demand and supply sides of the business manifest? Unlike many other venture-backed businesses, Airbnb has demonstrated its model's potential profitability, albeit in fits and starts. Airbnb reported $219 million in net income last quarter, a bright spot during an otherwise dark year. The business also reported profitability in 3Q19, 3Q18, and 2Q18.

Looking ahead, might lower S&M expenditures and reduced headcount support profitability on a go-forward basis? If 2020 has taught us anything, it's that the future is tough to predict. Nevertheless, investors will be buoyed by the durability of Airbnb's market power and Chesky and Co's sporadic ability to turn a profit.

The bad

Airbnb's financials would have looked considerably rosier had the coronavirus not intervened. With travel decimated, Airbnb had little option other than to raise $2 billion in debt and equity from Sixth Street and Silver Lake, as mentioned. That's left the company with meaningful liabilities in the coming years.

While the company currently has $2.7 billion in cash and cash equivalents and $1.8 billion in marketable securities on its balance sheet, its margin for error has narrowed thanks to the events of the past nine months. A 25% headcount reduction and the curtailing of operating expenses lighten the load, but will Airbnb be able to maintain sufficiently robust revenue growth to keep Wall Street happy?

Skeptics might point to pre-pandemic performance. Before the outbreak, revenue growth had slowed to 32%. While that still supported a long-term expansion story, it read as a disappointment to some, given Airbnb's relatively low penetration across its $3.4 trillion TAM. With 2020's other tech unicorns reporting far higher growth rates, there's a risk that investors could be blasé about Airbnb's trajectory. Parsing this momentum is made more difficult because the S-1 provides little detail on different customer types, such as those leveraging the platform for corporate travel. Subsequently, it's not straightforward to compare different cohorts' health and how they might be trending.

Finally, Airbnb's operating leverage is relatively high. Operating leverage reflects the relationship between revenue and operating income — a company with high operating leverage increases its profits as revenue grows. This is because said company's fixed costs are higher than its variable costs and make up a proportionally smaller percentage of sales during periods of growth. Airlines, with their high fixed cost structure and relatively lower variable costs, have high operating leverage. Companies with low operating leverage have comparatively higher variable costs.

Higher operating leverage, like Airbnb's, is great when revenue grows faster than expenses, but leverage cuts both ways. In the first nine months of 2020, revenue declined -32% but total expenses only dropped -22%. A bulk of the total cost savings came from COGS (-26%) and sales & marketing (-53%), with all remaining expenses only declining -7%. This suggests future cost cuts will be harder to come by if the company sees further revenue contraction, and means a return to pre-pandemic revenue levels is vital to achieving material cash returns.

The unknown

The success of any IPO rests on the market's belief in a business's future. Despite that common thread, Airbnb is unique in that so many aspects of the company's future are in flux.

What will the lasting impact of the pandemic be on travel? How will the mix shift of international vs. domestic stays evolve? Will business travel ever recover to pre-pandemic levels? Will the time and money invested in experiences be ROI-positive? Has Airbnb's relative competitive position actually improved given the decimation of other players in the space?

The questions are legion, and predicting how and when they will be answered is a task we lack the hubris to attempt.

That said, here's what we do know: Airbnb is selling a vision of the future materially different from the status quo in travel and leisure. Changing the world is rarely cheap, and with budgets constrained and higher liabilities, the path ahead is not without pitfalls. Airbnb is an established brand, and the uniqueness of its offering versus other travel businesses bodes well should a major recovery in global travel occur. That's one way of saying that while a case of absolute strength may be hard for management to make, the firm's relative strength is difficult to dispute. We'll soon know if that's enough.

Competition

Category creators enjoy the luxury of a lack of competition until outsiders realize the newly created category is valuable. As discussed, Airbnb is a magnificent story of category creation, so much so that they've become a cognitive referent.

The goal is not only to make sure that the product category takes off, but to become the firm that comes to define it—Google and Internet search, Starbucks and coffee, YouTube and video sharing...In some cases, the names of these companies are so inextricably linked to the actual product category itself that it becomes like a verb. We 'Google' it.

On its path to referential glory, Airbnb unlocked a new form of supply and elevated alternative accommodations into a global category. The challenge Airbnb now faces is defending what they've built as large incumbents and hyper-focused upstarts move in.

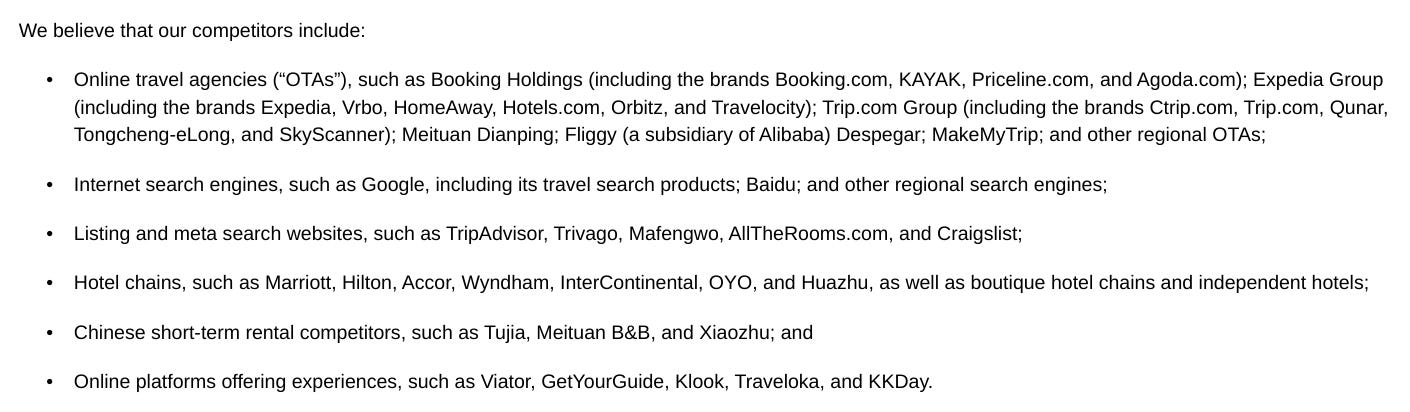

While many parts of the S-1 lack specifics, Airbnb provided a comprehensive taxonomy of their competition:

Rather than exhaustively covering how competitors can attack Airbnb, we think it's worth honing in on specific threats from two categories: incumbents and upstarts.

Incumbents

Before turning to true incumbents, it's worth discussing hotels. Despite being mentioned above, they do not represent direct competition given that Airbnb is a distributor, whereas chains like Marriott and Hilton are suppliers. As Skift's Seth Borko succinctly noted: "Comparing a travel distributor to a travel supplier is comparing apples to oranges. They have different business models, incentive structures, and challenges."

A more fitting competitor? Booking.com. While Airbnb's supply dwarfs traditional hotel chains, Booking has near parity in short-term rentals and a much broader base when including hotel rooms.

Investors should expect a fierce battle, as foreshadowed by CEO Glenn Fogel. He welcomed Airbnb's IPO, saying:

[C]ongratulations, Brian [Chesky], fantastic, enjoy being a CEO of a public company...We certainly will enjoy looking at their numbers instead of just hearing what they like to release. That will be an interesting thing, too.

The same article reported Fogel's intention to close the "brand awareness" gap domestically by investing in marketing. The upshot is clear: Airbnb may have created the category, but to keep it, they'll have to go toe-to-toe with one of travel's largest and most capable companies, all under the lights of the public markets.

Booking is just one incumbent, of course. Expedia holds designs on alternative accommodation through Vrbo, a competitor that absorbed HomeAway after the latter firm was acquired in 2015. As shown above, Vrbo is no slouch, with 2.3 million rooms.

Lastly, we can't talk about travel without mentioning Google. Both friend and foe to existing players, Airbnb took a small shot at the search engine in their S-1:

Changes to search engine algorithms or similar actions are not within our control, and could adversely affect our search-engine rankings and traffic to our platform. We believe that our SEO results have been adversely affected by the launch of Google Travel and Google Vacation Rental Ads, which reduce the prominence of our platform in organic search results for travel-related terms and placement on Google.

This has been a common complaint in recent years, most loudly vocalized by TripAdvisor, demonstrating the uneasy relationship all travel players have with Google. Again, Airbnb will lean heavily on their brand to drive direct traffic, yet they still need to capture new demand, which often means paying the search engine's toll.

Upstarts

As Airbnb battles large incumbents at one end, they'll have to keep an eye on smaller competitors.

Three low-end competitive sets might cause trouble: rising short-term rental platforms, professional tooling businesses, and hyper-focused vertical markets.

The most obvious category is the first. Businesses like Sonder, Stay Alfred, and Blueground leverage Airbnb as a marketing channel, sharing listings and receiving bookings through the platform. While this is mutually advantageous to some extent, ceteris paribus, insurgents would prefer to own the customer relationship directly, avoiding Airbnb’s fees in the process. Should these platforms succeed in this goal, Airbnb might find itself losing out on customers, particularly those looking for extended stays. In the long run, one can imagine these companies infringing on Airbnb's ability to capture more of the rental market, though there's likely space for all to take share from traditional realtors.

Concerning this competitive set, it's hard not to feel as if covid-19 may have been a blessing in disguise for Airbnb. Without cash on hand, equivalent access to capital markets, and similar brand equity, these businesses likely suffered even more than Airbnb. That's evinced by the closure of Lyric's core business.

Interestingly, that team has moved into the second space Airbnb may keep an eye on professional hosts' tools. Wheelhouse, which we mentioned during our "Case Study," is a Lyric spin-out and the business's new focus. While these products can complement Airbnb, they may extract value that Airbnb wishes to capture down the line. For example, you can imagine a banking service designed for professional hosts that could finance home improvements, smooth income, and even facilitate the purchase of new properties. Those features are unlikely to be a high priority for Airbnb in the short-term, but they are unlikely to revel in others profiting. Opportunistic M&A should be exercised to bundle new features into Airbnb's product suite and to take promising businesses off-the-table.

Finally, Airbnb will need to beware of being unbundled. When a company hears chatter that it might be vulnerable to unbundling, it's both good and bad news. On the one hand, only businesses of a certain size are perceived to be large enough to unbundle. On the other, it suggests there's room for competitors to attack specific pieces of the business.

There are signs that Airbnb could have a coming wave of vertical unbundlers. Increasingly, startups are gaining traction, billing themselves as the "Airbnb for X." For example, Hipcamp is considered the Airbnb for camping, while RVShare and Outdoorsy offer a similar playbook for camper vans.

Airbnb proved that what looks like a niche can be a vast category when everyone is connected online. Suppose hyper-focused aggregators narrow in on specific types of alternative accommodations. In that case, elements of Airbnb's unique room supply — Airstreams, tiny homes, eco-conscious dwellings, yurts — could splinter off into other, smaller marketplaces.

Covid-19

Though we've covered parts of this story elsewhere, it's worth digging into covid-19's effect on the travel industry, Airbnb, and consumer behavior.

To put it mildly: the coronavirus hit the travel industry hard. With borders closed, businesses shuttered, and consumers sheltering-in-place, travel reached a standstill this spring. For example, by mid-April, the number of passengers moving through TSA checkpoints at US airports was down about 95% YoY. No y-axis was safe.

While the percentages vary, most travel industry metrics follow a familiar trend: a precipitous dropoff in the spring, followed by a gradual recovery. As we've mentioned, Airbnb is no exception, though they did fare somewhat better than many others. Booking growth decelerated in February, turned negative in March, and bottomed out at a 72% YoY decline in April. Cancellations skyrocketed as guests were either unable to or uncomfortable with traveling. Indeed, the number of "Nights and Experiences" canceled in March and April exceeded the number booked. This metric recovered in May and June and has stabilized at down 20% YoY since. The number of active listings held steady at 5.6M.

As discussed previously, when faced with sagging demand, Airbnb's management acted decisively to cut costs and solidify its balance sheet. Marketing, design, and customer service teams were cut particularly deep, while employee bonuses and executive compensation were slashed. Laid-off employees were given at least 14 weeks of severance, a year of health insurance coverage, accelerated vesting, and various job support services. In a time of crisis, management was thoughtful in its stakeholder actions. Beyond the $250 million Airbnb gave hosts to mollify the $1 billion guest refunds, the company provided an additional $17M for Superhosts.

Investments that didn't directly support hosts were sidelined or eliminated. Airbnb paused or scaled back 70 of its 130 projects, including Airbnb Magazine, Airbnb Studios, hotels, Luxe, and a planned transportation offering. It also revamped its marketing messaging to focus on belonging and connection.

As alluded to earlier, the pandemic seemingly altered preferences, changing how consumers interacted with Airbnb's product.

One example was the shift in preference toward domestic travel. Historically, Airbnb over-indexed on international trips. In 2019, nearly half of nights booked were for international journeys, above the travel industry average of 20%. In September 2020, 77% of nights booked on Airbnb were for domestic trips. Indeed, this preference for proximity manifested even on a smaller scale: Airbnb's bookings rebounded most sharply within 50 miles of a guest's home. By contrast, trips more than 500 miles away saw the weakest recovery.

Travel also became more distributed. Guests sought rural destinations and looked for longer stays. GBV for stays over 28 nights was up 50% YoY in September 2020. Perhaps surprisingly, guests started booking trips with shorter lead times. In the third quarter of 2020, guests booked 23 days out on average, compared to 35 days the year prior.

As travelers' needs changed, so did Airbnb. The company updated its website and app to promote nearby and non-urban destinations. In June, it developed a five-step enhanced cleaning protocol in partnership with former US Surgeon General Dr. Vivek Murthy. And with physical experiences on hold, Airbnb shifted Experiences online, launching the reformed product in two weeks. Nearly three months later, in late June, the revamped Experiences had brought in bookings of about $1 million, illustrating the project's comparatively small scale.

In its totality, covid-19 has exposed Airbnb's vulnerability to macroeconomic shocks while highlighting the adaptability of management and the robustness of the product. As travel preferences shifted with the pandemic, Airbnb was able to satisfy them, drawing on its base of 5.6 million listings spanning igloos, private islands, and treehouses.

With a second wave of the virus spiking in Europe and North America, Airbnb's adaptability and resilience will continue to be tested. Indeed, with much of Europe again under lockdown, Airbnb expects to see YoY booking declines in the fourth quarter of 2020 compared to the third quarter. The company isn't out of the woods yet.

Why now?

With IPOs in 2020, the question is less why now? and more, why not? In March, the world looked very different. Second-guessing Airbnb's survival was at all-time highs, flash-forward to November and its Nasdaq that's pushing its upper-limits. Given the love-in tech unicorns have received since spring, it would be irresponsible for Airbnb not to take advantage of this window.

Strategically, a public listing will also give Airbnb access to capital at a time it may need it. That may allow the company to snap up or squeeze out stumbling competitors. From an investment standpoint, Airbnb may represent an attractive "hedge," as enunciated by Box CEO Aaron Levie:

Airbnb IPO is the perfect market hedge. If you believe the vaccine is coming quickly, people want to travel again. If you don't believe it's coming quickly, people want to work remotely in different locations longer.

We'll see if the market sees Airbnb as quite such a no-loss proposition.

—

Disclosure: One of the S-1 Club's contributors works for an investment firm with a holding in the LTSE.