Chip War's Chris Miller on Putin, China, and The Future

The historian and writer shares his thoughts on great power conflict, Japanese economic history, and flawed utility functions.

To understand the future, ask a historian.

Though it may sound counterintuitive, there is no better way to understand the texture of the present or the possibilities of the coming decades than by talking to those who study the past. Often, they see the shape and structures of our world especially clearly and can extrapolate with greater fidelity.

For this reason, I am particularly excited to share our newest edition of Modern Meditations with Chris Miller, perhaps my favorite contemporary historian. For those unfamiliar with Chris’s work, he is an associate professor at Tufts University and the author of Chip War, a stunningly good chronicle of the microchip industry, justly acclaimed by just about every publication upon its release. It does an exceptional job charting the rise of companies like TSMC and ASML, shading the still-growing geopolitical power struggles, and portraying the vibrant characters behind the industry. It also illustrates our point – if you’re interested in grasping the world of tomorrow in all its complexity, Chip War is a brilliant starting point.

In today’s interview, Chris and I examine his views of the present and future, touching on the un-economic motivations of great founders, changing perceptions of Vladimir Putin, supplying technology to China, and IBM’s work in Nazi Germany. It proved a fascinating, wide-ranging conversation in which I learned a great deal. I hope you will, too.

50 game-changing startups – all in one place.

A few weeks ago we released the inaugural edition of Future 50, a database featuring the world’s highest-potential startups, supported by our friends at Mercury.

The Future 50 is the result of months of collecting nominations from leading VCs, researching different companies, and reviewing private data. You won’t want to miss it. Here’s a sneak peek of the startups you’ll hear about:

The AI company detecting wildfires faster

The “Saudi Aramco of carbon removal” reforesting the Amazon

The maternal healthcare provider that’s already impacted 3M lives

The tech-powered trucking company that’s surpassed $45M in revenue

…and 46 others. Each company is accompanied by a detailed description and clear rationale of why we think you should have it on your radar.

Lessons from Chris

Beware the utility function. Chris’s work studying powerful nations and people has led him to appreciate the limitations of strict economic analysis. Both countries and entrepreneurs are often driven by less tangible motivations like a desire for power, glory, or reputation – none of which fit neatly into an economic utility function. Those that study these different actors too narrowly risk missing their essence.

History as the base layer. Given his vocation, it’s unsurprising that Chris considers history the best lens to understand the world. He makes a compelling, articulate case, explaining how the field offers insights into how systems and individuals change over time. Subsequent lenses – whether economic or cultural – sit atop it. But history provides the foundation.

Betwixt and between. The risk of a great power conflict breaking out is significant, according to Chris. Though the risk in a given year may be low, over a decade, it seems substantial. Yet, we think about this possibility very little and aren’t preparing for it properly. Under President Biden, America has favored a mixed approach, offering limited concessions and relying on some level of deterrence. It would be more coherent to lean into one of those two strategies.

We know the future. At least, in broad strokes. Chris argues that the most critical technologies of the coming decades are already appreciated. We know that space travel, genetic engineering, and brain-computer interfaces will play significant roles, we just don’t know precisely how they’ll be expressed.

1913 or 1990? Our current era is defined by intense technological investment and deployment, rising geopolitical competition, and the politicization of international economics. In that respect, it resembles the period before World War I and the 1990s. We should very much hope for the latter.

Which current or historical figure has most impacted your thinking?

Vladimir Putin. He is the most striking embodiment of my belief that you can’t understand people through traditional utility functions.

My background is in Russian studies, and I’m struck by the extent to which our analysis of Putin has changed over time. Twenty years ago, when he first came to power, he portrayed himself – and with some level of accuracy, I think – as a relatively modern leader of Russia. He was reforming the tax system and doing stuff that political leaders do. When we talked about his motivations at the time, the focus was often very financial. I remember very distinguished economists who I respect greatly saying, “Isn’t it the case that Putin is primarily driven by money?” And indeed, there are lots of examples of Putin being hugely corrupt and his friends stealing all sorts of stuff. He’s got his gaudy palaces on the shores of the Black Sea.

But we’ve learned that it’s not all about money. When he invaded Ukraine in 2022, Putin cited Peter the Great and Catherine the Great as justifications for territorial conquest. It’s an illustration that “modern people” are not always driven by modern impulses. The desire for power and glory and control, the desire to be on top and dominate others – for better or worse - are central to many people’s utility functions. These impulses might seem more base, but I think, to some degree, they’re present within all of us. You ignore them at your peril.

What are you obsessed with that others rarely talk about?

Five years ago my answer was semiconductors. Today, it’s probably Japanese economic history. I’m not sure I’m truly obsessed with it, but I have ordered too many books on Japanese history. In general, I’m a believer in trying to read very, very widely. Every summer I give myself a period of aimless reading, pushing the boundaries in different directions, not knowing what the take away will be.

So far, I would say my reading has gotten me interested in the chemicals industry. It’s an industry that’s never been given a treatment that reflects its importance in modern life. When you ask yourself, “Where are petrochemicals?” The answer is, “Well, they’re in everything.” But I don't think there’s a really good book on petrochemicals and its impact on the modern world. That book ought to be written, but at the moment, to understand how that industry developed and functioned, you have to piece it together from twenty different books.

You discover all sorts of interesting questions by doing this kind of reading. For example, the leading producers of chip-making chemicals are Japanese. These are ultra-specialized, ultra-purified chemicals that have dominated the industry for 50 years. Yet, no one had a good explanation for why that happened. People will just say, “Well, of course, Japanese companies are good at chemicals,” but there’s no rationale that I’ve found.

What craft are you spending a lifetime honing?

I would say there are two.

First, understanding how things work. I think it’s a craft that you get better at over time as you look at different institutions, organizations, and social structures and observe how they interact and function. I do that as a historian, which has always seemed like the best lens for making sense of the world. You get to explore how systems and individuals change over time. And you can layer other modes of understanding on top of it: economics, institutional analysis, culture, and environment. All of those, and many others, can be layered on top of history.

Second, writing. There are some people who are born brilliant writers, but I think it’s mostly a matter of reading and writing and thinking about how to become a better reader and writer. Across the books that I’ve written, I’ve challenged myself to write in different genres as a way to improve my craft. The historians that I admire most – people like Paul Kennedy and John Gaddis – are able to write great books in multiple genres. It’s a great intellectual challenge to try to tell stories and explain ideas in different ways.

The best historians are also great storytellers. There needs to be analytical rigor, of course, but my favorite history books are the ones with extraordinary stories and fascinating personalities sitting alongside the big economic, social, and institutional factors. It’s one thing to say that history is driven by people and broad structural forces, which is always true; it’s another to show how that happened in a given context.

What is the most significant thing you’ve changed your mind about over the past decade?

I’ve changed my mind about the usefulness of thinking like an economist. Even though I may criticize them sometimes, I have great admiration for economists. But they think of everything in terms of utility functions and how to maximize them. They only know how to calculate that in dollars and cents. Though that’s valid, I’ve come to appreciate its limitations.

I’ve spent a lot of time over the past decade studying great entrepreneurs and geopolitical competition. Fundamentally, neither founders nor countries think like economists. Great founders may have shareholders who would like them to consider return on equity, but that’s not how they make decisions. Think of Jensen Huang ten years ago – even though Wall Street was warning him against it, he still poured Nvidia’s money into building out CUDA and the ecosystem around it. If your mode of thinking is purely economic – focused on return on equity or maximizing shareholder value – you miss a lot of what actually drives competitive, successful people.

The same thing is true at the international level. Governments don’t think like economists, either. They try to maximize glory or territory or reputation or power. Like great entrepreneurs, sometimes they simply want to win, just for the sake of besting an adversary. There are ultimately so many things that drive nations and the humans within them that are non-quantifiable. Often, they’re much more significant than strictly quantifiable economic variables.

What trait do you value most highly in others?

I knew someone who used to say, “Tell me something I don’t already know.” That can be a bit obnoxious, but it captures something I value. My favorite conversations are the ones in which I learn something, especially from a sphere I’m unfamiliar with. I really appreciate people who are creative thinkers who can articulate new ideas and push the intellectual audience.

So many of our conversations are filled with platitudes or things that are already widely known and, therefore, don’t deserve to be said again. Those conversations aren’t worth having.

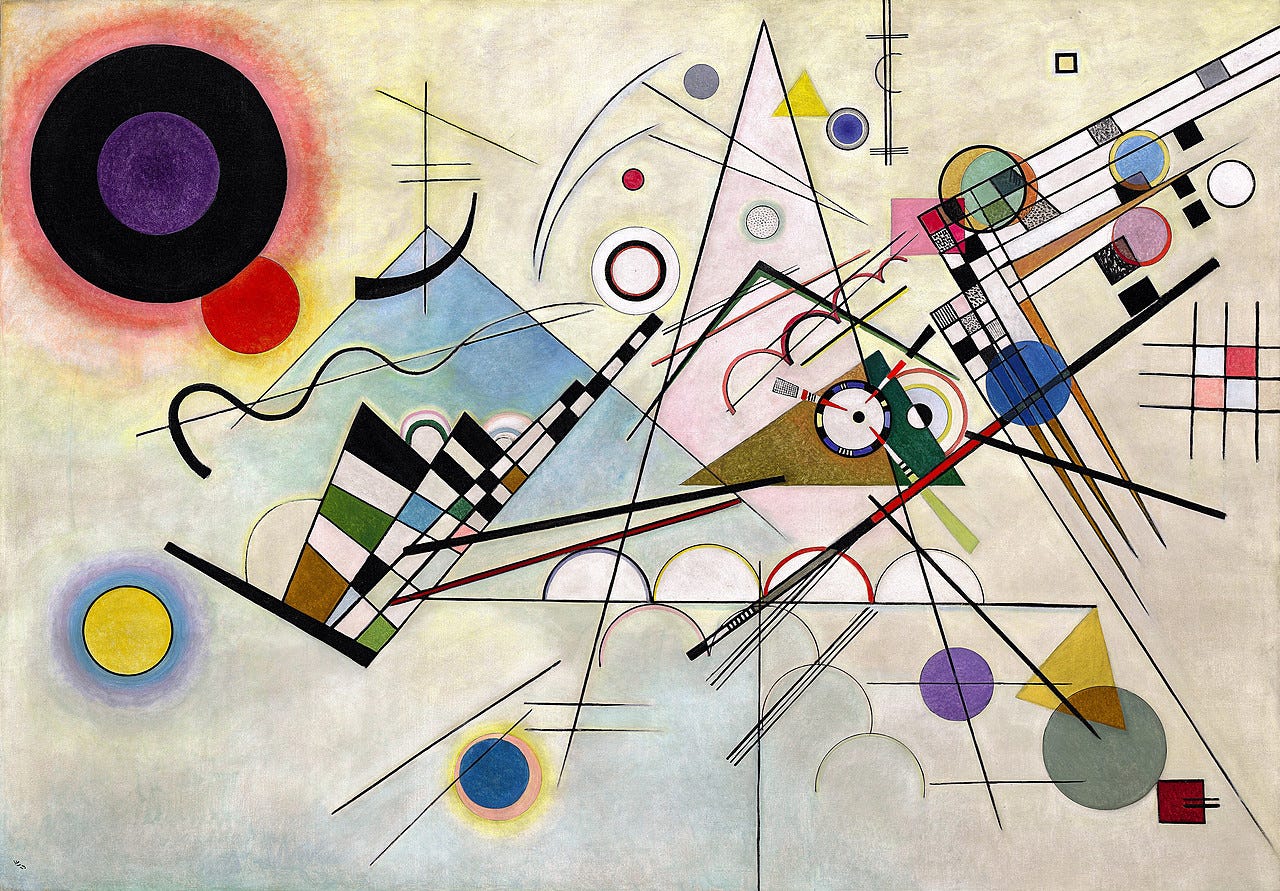

What piece of art can you not stop thinking about?

I find the abstract art of the early 20th century most intellectually interesting. These artists were responding to radical social and intellectual change and were using art as a way to both represent and respond to that. They were pushing the envelope in a way I can connect with. Conversely, I struggle to connect with modern contemporary art, for better or worse.

Wassily Kandinsky is a favorite of mine. What I like about his work is the sparsity of elements; there’s a whole lot of white space. When you look at one of his paintings, you know that each of the pieces are there for a reason and I find it really appealing to try and understand how they interact and fit together. In a way, it’s a similar process to taking an X-ray of an organization, and seeing all of the different moving pieces.

What would you be doing if you hadn’t pursued your current professional path?

What I really enjoy is trying to understand how stuff works. You hear engineers say that – it’s why they want to take apart different devices and gadgets. For me, it’s about understanding how institutions, social structures, and economies work at their core. I want to understand how these complex groups of people work together in interesting ways – that’s what really interests me.

You tackle those intellectual questions through a lot of different spheres. My approach has been to do that through academia – studying and teaching history. But economists do it for macro-economies and the more interesting analysts do it for their given industry.

I’m not sure there’s another job that would be a good fit for me. I’d enjoy the intellectual aspects of some of them, but not the day-to-day. For example, I love watching a financial analyst tear down a company just by looking at its balance sheet. But would I want to be a financial analyst full-time? No. The same is true of good consultants – they can look at a company or institution, grasp its structure, and understand how it ticks. But would I want to be a consultant? No.

I’ve learned a lot from people who work in these roles and definitely admire some of the X-ray vision they have when analyzing companies, but I don’t think I’d enjoy doing it.

If you had the power to assign a book for everyone on earth to read and understand, which book would you choose?

I really admire Dan Yergin’s The Prize. It’s a history of the last two hundred years through the lens of the most important industry of that period: oil. It’s got it all: the personalities, business, geology, politics, and wars that defined that period. I think you could do no better in understanding why the world is structured the way it is than by reading that one book.

What contemporary practice will our descendants judge us for most?

I’m not someone who believes very strongly in judging people historically. If you’d asked people 100 years ago the same question, I suspect they’d often know what they’d be judged for but didn’t always have the ability to rectify their actions. Therefore, I don’t think we can be fairly judged by people 100 years into the future, just as we can’t fairly judge them.

If I had to guess, I suspect that eating meat will be perceived poorly in 100 years. And that we’ll be judged for tolerating the level of inequality we do.

What will the next generation do, or use, that is unimaginable to us today?

I think we know the trajectory of technological progress in broad strokes. If you go back fifty years ago, you can find Gordon Moore talking about personal, portable communication devices. It was hard to imagine in detail what that would look like, but he got the basic schtick.

Because of that, I don’t know what part of our future would be inconceivable to us. I think it’s very possible that our children will go to space as the cost of spaceflight declines. I think we’ll have much better brain-computer interfaces – that’s already happening. Genetic engineering will be a sphere of great progress. Ultimately, we know what the big trend lines will be. We just can’t predict them exactly.

What risk are we radically underestimating as a species? What are we overestimating?

We’re underestimating the risk of a great power conflict – World War III. World wars happen roughly every half-century. We shouldn’t forget that. Whether as part of a world war or not, the risk of a nuclear weapon being used in conflict within the next 50 years also seems highly plausible.

You can see points of tension across the border between China and the Western sphere. You see it in the South China Sea with the Philippines, in the East China Sea with Taiwan, and in the Himalayas with India – and those are just the border disputes. It’s easy to imagine how that could spiral in an escalatory manner.

If you put a dollar value on the cost of this kind of conflict, it would be measured in the many trillions. Yet the amount of time we spend thinking about it is not remotely commensurate with that outcome. Some people console themselves by saying, “It’s high magnitude but low risk, so the expected cost is low.” I’m not so sure about that. If you talk about the risk this year, maybe it’s low. But if you think about it over the next decade and factor in the risk compounding every year, suddenly, I don't think those assumptions hold.

If you think the risk is high, we have two options. You can either offer concessions or build up your capabilities to deter more successfully. From the US perspective, we’ve been doing a little bit of the latter and a little bit of the former under Biden – but not much of either. I think it’s intellectually coherent to say, “Let’s do more of one or more of the other.” I think it’s not intellectually coherent to say, “Let’s just do a little bit of both,” when in reality, defense spending is at historic lows relative to the post-Cold War period.

What’s the last piece of media you loved?

Most of the media I consume is written. The last book I read that was exceptional was Mitsui by John G. Roberts, a chronicle of the Japanese conglomerate. That company is the ultimate survivor of Japan’s business and political worlds, having lasted through over 300 years of history, enduring revolutions and changes in government. Part of the reason Mitsui survived was because it had the wisdom to fund both sides of an election or revolution. It really is an extraordinary view into how Japan operates and has operated for many centuries through the lens of one of the most significant companies and economic operators. It’s been my most fun piece of summer reading.

It surprises me how many hugely influential companies have no books, or no half-decent books, written about them. After reading Mitsui, I tried to find good books on Mitsubishi or Sumitomo. As far as I can tell, there aren’t any, at least in English. The same goes for British Petroleum. Dan Yergin’s book The Prize covers a lot, but it’s not specifically focused on the company.

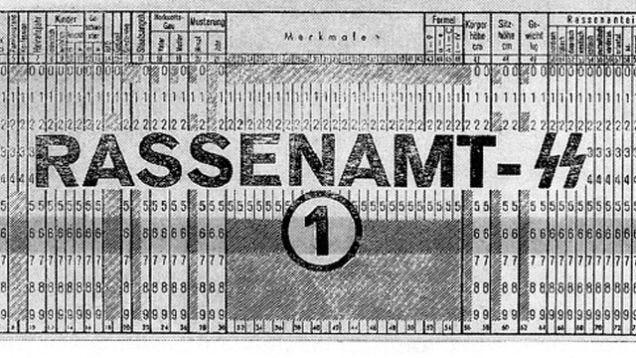

There are a couple of okay books on IBM, but nothing fantastic. There is a great book on one chapter of IBM’s history called IBM and The Holocaust by Edwin Black that I read last year. It’s a remarkable look at IBM’s sales to Nazi Germany in the 1930s. This was before digital computers, of course; they were selling the kind of machines that used punch cards to compute. The Nazis performed a bunch of censuses to categorize everyone by race, and IBM provided the machines that helped them do that. Mr. Watson, the chair of IBM, had deep relationships with all of the Nazi leaders and, as late as 1938, was going to Germany to meet with Göring and other senior officials. Inside of every concentration camp, they had IBM machines tabulating who was arriving in the train cars. It was a horrifying, horrifying read.

That book was published about two decades ago, but to me, it’s actually a really live issue. Today’s US tech firms are dealing with a similar set of dilemmas with regard to Xinjiang (which houses China’s internment camps). I don’t know that any American companies are as deep as IBM was with Nazi Germany, but the basic dilemma is kind of the same. If you’re giving governments tools to gather, categorize, and analyze data, how are they using it?

How will future historians describe our current era?

It depends on the lens you take. If you’re looking at the history of the United States, that’s one lens. If you’re looking at the history of technology or the history of the world economy, that’s a different one.

It seems to me that there are three key dynamics of this era. One, an intensification of the investment in and deployment of advanced computing. “AI” is the phrase used this year, but it’s a longer-term trend. Two, the intensification of geopolitical competition. And three, the politicization of international economic life, which for the past 20 to 30 years was not really driven by political factors. Today, it certainly is.

As the saying goes, “History doesn’t repeat itself, but it often rhymes.” The scary rhyme with our current period is with the pre-1914 world, before the advent of World War I. In addition to being geopolitically tense, that was also a period of technological advancements. Railroads were economically transformative and good in many ways. But they also brought people closer in ways that weren’t always positive. It was railroads, for example, that enabled the large European empires that formed. If you think of European empires in 1800, they basically ruled coastal areas or small islands. For example, the British ruled the coast of Canada, some Caribbean islands, and the coast of India. By 1900, every European empire had penetrated inland very deeply, enabled by railroads. It’s impossible to imagine African colonization without that technology.

The positive rhyme is with the 1980s and 1990s. You have the application of computing to every sector of the economy in that period, leading to huge productivity advances in the 1990s and 2000s. The optimistic view of all the computing investments we’re making today is that we’ll find a whole new set of applications which will meaningfully speed up economic growth.

The Generalist’s work is provided for informational purposes only and should not be construed as legal, business, investment, or tax advice. You should always do your own research and consult advisors on these subjects. Our work may feature entities in which Generalist Capital, LLC or the author has invested.

Thanks for this great read. The prize has been on my "to do" list for some time so will definitely read it now. I also was completely aware of the IBM episode. Another very useful nudge.

Really thoughtful conversation - got me to open a few new browsers tabs which it my measuring stick for things like this.