He was an old man by then. Blind, living in the ruins of his palace, what was once his empire in tatters around him. A contemporary described Shah Allam II, emperor of the Mughals, as a “wretched King of shreds and patches." By 1803, Allam's kingdom was particularly threadbare. His old enemy, the British East India Company (EIC) had bested him once again, capturing Delhi.

The EIC was a formidable foe, an organization such that the world had not yet seen. Established in 1599 with a charter from Queen Elizabeth I, then in her mid-60s and heavily daubed with signature white-lead, the EIC was a private company founded to pilfer and trade the riches of the East. In that aim, it was given a broad mandate, able to "wage war" according to its corporate documents, something it did almost immediately by capturing a Portuguese vessel on its inaugural journey in 1602. Greater corporate violence would follow, particularly once the EIC made inroads in India. Amassing a private army of 260K men, double that of England's own military at the time, the EIC succeeded in forcing a young Shah Alam to privatize the operations of his empire, surrendering administration and tax-collection of Bengal, Bihar, and Orissa to the corporation. Forty years later, it finished the job, ripping the last of Allam's riches from the Shah's gnarled fingers. By then, the EIC had spread across the world, tendrils touching the new American colonies and China, further East. This was a different sort of company. It was a corporation as a state, a "meta-state," richer and more powerful than many nations, including at some points the country that had birthed it. Though the English parliament later sought to curtail the EIC's power, by then it was too late: the company had the funds to buy off politicians, protecting its influence through capital. That insinuation ensured that Parliamentary legislation served the EIC's shareholders as much or more as they did the British body politic.

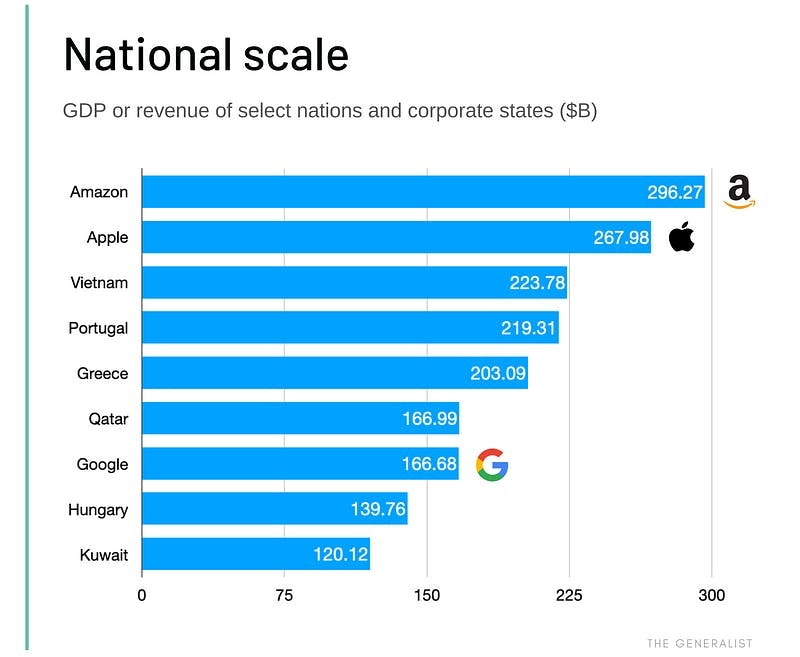

The EIC bears more than a passing resemblance to the tech giants of the current era. Over the past decade, companies like Apple, Amazon, Facebook, and Google have reached a scale rarely seen since the EIC loaded ships with spices. In size, they already eclipse the economy of many countries. With a 2019 revenue of $296.27B, Amazon surpassed the GDP of Portugal, Greece, and Qatar. So too, Apple. Google exceeded Hungary, Huwait, and over 100 others.

This ascent has been aided by the lenity and ineptitude of (many) nations themselves, courting favor through tax allowances, bickering along polarized party lines, postponing digital transformation, and legislating at the pace of a pre-internet era. Soon they may even surpass superpowers like the United States in influence. In some ways they already have.

Thomas Jefferson wrote “The care of human life and happiness, and not their destruction is the first and only legitimate object of good government." Over the past three months, the US has demonstrated an inability to protect the health of its citizenry, failing to deliver basic services in the pandemic. In its baldness and viciousness, the death of George Floyd hammered home the scandalous condition of the republic. It is little wonder that in 2019, just 4% of Americans said they had a "great deal" of faith in Congress. It must be lower now.

Companies are stepping into the vacuum of power. While the the US government has dithered, unable to orchestrate mass testing or effective collaboration between state healthcare systems, Amazon has become even more of a public utility. The fact that a short outage this Thursday made major news is indicative of its importance.

We are one nation under Bezos. So, too Zuckerberg, Cook, Pichai, and to a lesser extent, Musk and Dorsey. Beneath them is a cohort of minor kings, barons of meta-dominions. This week saw several of those men expand their reach and further showcase the emerging frailty of the state.

Beyond a rare moment of weakness illuminating their necessity, Amazon was reported to be sniffing around autonomous vehicle company, Zoox. If completed, it would move the company closer to total domination of shipping and logistics, further edging out UPS, FedEx, and even the US Postal Service. USPS, a government agency, is already susceptible to Bezos' power: the organization subsidizes Amazon's packaging costs to avoid losing its biggest customer.

Like many of us may have, Musk spent much of Saturday watching the SpaceX launch. Though a magnificent achievement, the Crew Dragon's voyage represents yet another encroachment. What was once the sole purview of NASA is in the hands of a private business.

Facebook will hope a new coat of paint will aid their quest to build the internet's reserve currency. Zuckerberg's fingers are crossed that renaming the company's digital wallet "Novi" will help create distance between that service and the broader Libra coalition. Facebook is at pains to portray the latter as an independent organization to earn regulatory approval.

Zuckerberg was also entangled in the debate that raged around Twitter's decision to label some of the President's tweets for their lack of veracity, and incitement to violence. Whatever side of the debate on which you land, the fact that a sitting President sees fit to issue an executive order to narrow the powers of social media platforms indicates the wariness with which one state observes the other.

This is not a paean to a lost public sector, the ghost of some glorious apparat. We should be glad, in some instances, for these meta-states. If Musk were not hellbent on sending humans back into orbit, it may be some time until American soils hosted such an endeavor. If Bezos were not so dogged in his empire-building during pandemic, it is unlikely Americans would receive the necessities they need. We should expect his company to be the most effective way to disseminate vaccines when they become available.

But even if there is some good done, let us be under no illusions. These are also the companies that will, and do, manipulate and surveil us. A king is a king whether they set sail beneath the pennon of the Union Jack, or a smiley-faced logo. We should know what we are losing, what we are becoming.

That was the question Horace Walpole, a writer, asked in the 18th-century. He was disgusted by the influence wielded by the East India Company, the success they'd had overrunning and buying the levers of political power.

"What is England now?" he asked. "[It is] a sink of...wealth, filled by nabobs...a Senate sold and despised."

As the nation-state fails in its basic duties to keep its people safe, as companies begin to take on power beyond their original form, it may be time to echo Walpole and ask: What is America now?