Who is this for?

Founders. Whatever your business's maturity, it's worth understanding the strengths enduring, high-performers develop on their path to sustained dominance.

Investors. How can you identify a compounder? Investing in Netflix in 2011 might look like a no-brainer now, but it was far from a sure thing at the time. We'll discuss characteristics compounders share, along with some common traps.

Learners. Tech businesses increasingly dominate the financial markets. Understanding what a best-in-class company looks like and how they use technology and capital to their advantage will influence how you choose to allocate and grow your wealth. You'll also learn about the history of several breakout businesses.

Jay-Z understands the value of compounding interest. Towards the end of "Dead Presidents II," regarded as one of the greatest rap songs of all-time, Jay-Z drops a line about his finances:

You already know: you light, I'm heavy, roll heavy dough Mic-macheted your flow Your paper falls slow like confetti, mine's a steady grow

Easy enough to dismiss as another example of lyrical bravado perhaps, though it's complicated by the rapper's success as an investor: he's the first hip-hop artist to accumulate a $1B fortune; one of the few entertainers across mediums. Even the Oracle himself gave his benediction. After the two men met in Omaha in 2010, sharing strawberry malts, Warren Buffet said, "Jay is teaching in a lot bigger classroom than I'll ever teach in. For a young person growing up, he's the guy to learn from."

As with every story of wild financial success, Jay-Z's wealth is the result of innumerable decisions — lucrative joint-ventures, private investments, and product releases — but there's a fundamental force beneath each of them, referenced in the bars above.

The steady grow of capital — money begetting money. A genius of a different field expressed it more directly, "Compound interest is the eighth wonder of the world," said Albert Einstein. "He who understands it, earns it; he who doesn't, pays it."

Compound interest rules the world around us, powering the accumulation or destruction of wealth. Though many will know this power intimately, allow me a brief example:

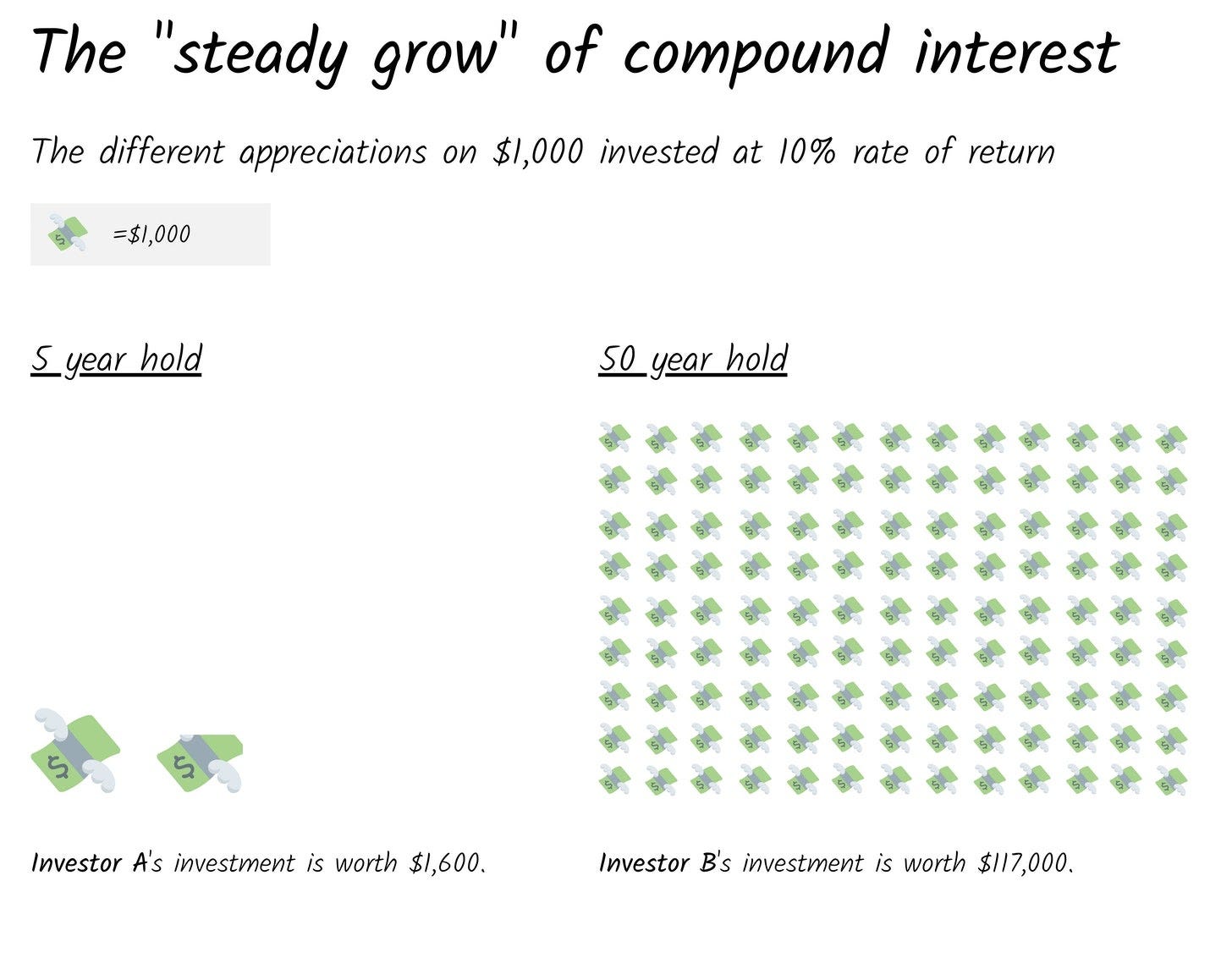

Imagine you invest $1,000 at a 10% rate of return for five years. By the end of that period, you've earned ~$1,600, a 1.6x return. Not bad.

Now, envision you invest the same amount but hold for 50 years. While we might expect a return of 16x on the initial investment — after all, you've multiplied the time frame by 10 — the true return is ~117x. The $1,000 you invested is now worth over $117,000.

The difference between the 16x you might reasonably expect and the 117x received is the result of compound interest. As interest grows the investment size, you begin to receive "interest on interest," leading to exponential rather than linear growth.

Just as the thrifty individual leverages the power of compounding to build their wealth, a small subset of businesses has managed to do the same.

Compounders: A Definition

"From the most hated to the champion God flow/ I guess that's a feeling only me and Lebron know" — Kanye West, "New God Flow"

—

In his rookie season, a fresh-faced LeBron James averaged 21 points a game. That's an impressive return, and one he bettered in the years ahead. Thanks to his sustained performance, James has become something of a poster-child of enduring brilliance, eking out further marginal gains year after year. But even he doesn't come close to the kind of growth compounders achieve.

Anouk Dey and Jeff Müller of Columbia Business School define a compounder as a company that sustains 20%+ annual returns over ten years, or the equivalent of a cumulative 620% return, a definition others have suggested. T. Rowe price refers to businesses with double-digit annual growth. To put that in perspective, if James had been able to increase his points per game output by 20% over a decade, he would average 130 each time he hit the court.

Companies achieve this insane growth by leveraging competitive advantages to gain incremental market share and generate high returns on capital. These compounders then reinvest cash flows back into the business, producing higher cumulative returns over time, creating a compounding effect that manifests in rapidly growing revenues and stock prices.

These companies also don't always look like you'd expect them to, either. Over the past ten years, four of the most successful investments include Domino's Pizza (DPZ), Extra Space Storage (EXR), Align (ALGN), and Netflix (NFLX). Each of those three returned at least 700%, outperforming the S&P500 (SPX, 190%) and tech giants like Facebook (FB, +577%) and Google (GOOGL, +443%).

If asked in 2010 which companies would prove the biggest winners of the decade, few would have picked a beleaguered pizza chain, a storage company, a dental-tech business, or an entertainment firm halfway through a pivot.

But look a layer deeper, and all four possess traits common in compounders.

Common characteristics

"Driven by my ambitions, desire higher positions / So I proceed to make Gs, eternally" — Tupac, "Unconditional Love"

—

Beyond exceptional returns, compounders share similar qualities. As alluded to above, these businesses usually have substantial competitive advantages, the ability to reinvest earnings and operate in an underpenetrated market.

Competitive advantages

To paraphrase Tolstoy, "Strong businesses are all alike; every weak business is weak in its own way." Which is to say compounders benefit from classic competitive advantages, including network effects, a strong culture, differentiated IP, and a compelling brand.

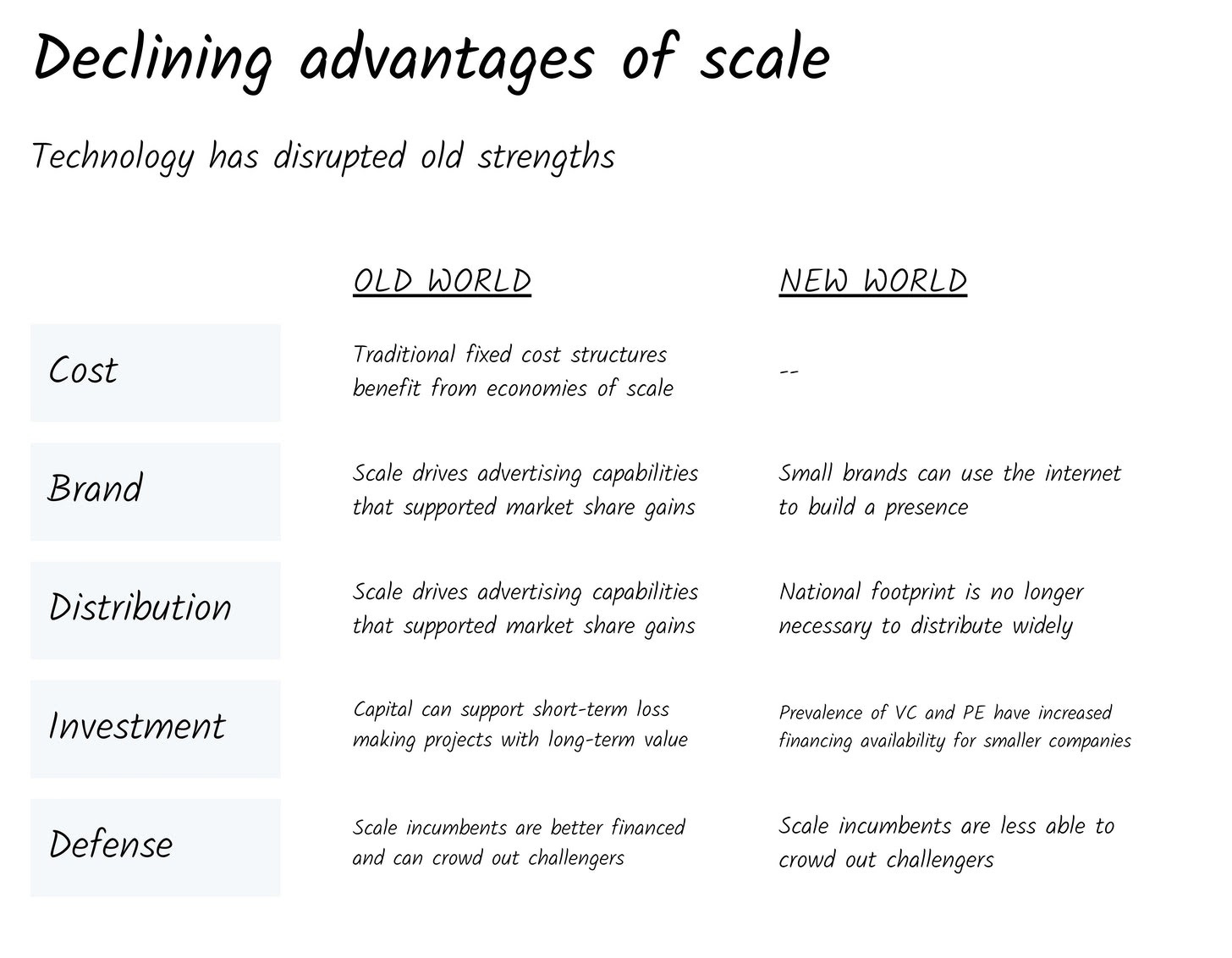

Not all appear equally — when studying compounders of the past, the importance of scale comes to the fore. Many previous compounders like Sears garnered strength from size, their stature granting the ability to reduce costs, grow exposure and distribution, and leverage their finances to support projects only valuable in the long-term. Businesses of a smaller size have traditionally not had such luxuries.

Those advantages remain robust, but technological innovations have eroded some. National brands have become less important, with more accessible advertising online. Distribution no longer requires a national physical footprint (think why Netflix beat Blockbuster), and the availability of capital thanks to VC and PE has reduced financial barriers.

Virtuous Reinvestment Cycles

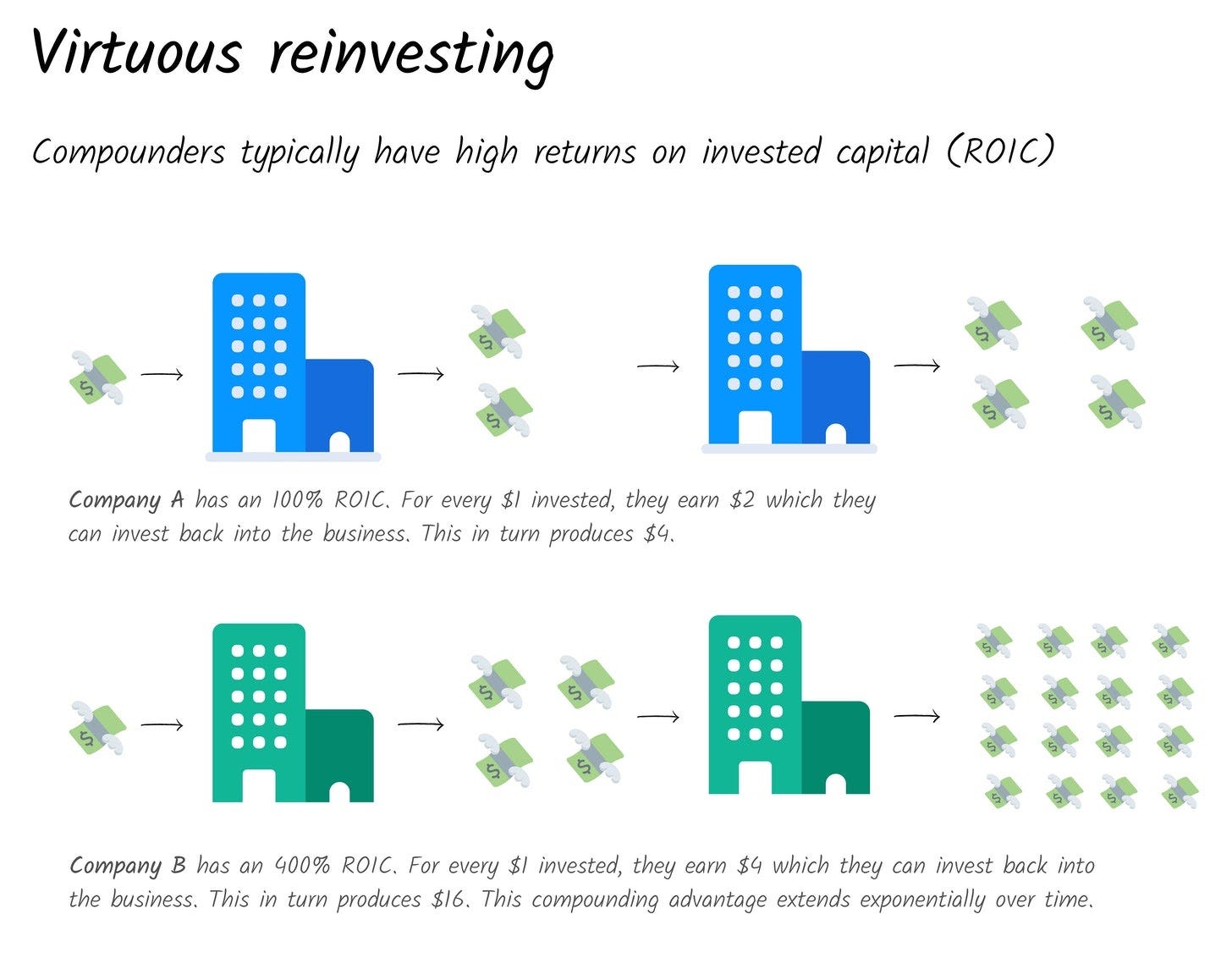

When you have a business model that turns $1 into $2 (with $1 of earnings on your $1 investment), the best thing a company can do is reinvest its earnings. The better a company is at converting invested capital into future dollars — the higher the return on invested capital (ROIC) — the more likely it is to be a compounder.

Typically, companies with high ROIC demonstrate a combination of high recurring revenues, high gross margins, and low capital intensity, which generates strong free cash flow (FCF) that can then be reinvested. The result is a virtuous cycle that grows additional FCF in the future.

An added benefit of high ROIC and FCF is that it increases the appeal of another version of reinvesting: M&A. A compounder applying a better business model can take a growth shortcut via M&A, applying its business model to a larger asset base. In effect, compounders gain more from M&A than other bidders, and thus, compounders can afford to bid higher, meaning they win deals more frequently.

Underpenetrated TAMs

In a canonical post on the internet and entrepreneurship, Chris Dixon noted, "The next big thing will start out looking like a toy."

That phrase has led to the concept of a "toy market," an opportunity that appears trivial and small before becoming ubiquitous. Businesses like Twitch, Uber, and WeWork all appeared to be serving a small customer base at first, before scaling rapidly (albeit with different results). What seemed to be niche products were just ahead of a broad, secular trend.

Compounders often find themselves in similar circumstances, tackling underpenetrated, fragmented markets with room to grow.

Mirages

"I leave scientists mentally scarred, triple extra large / Wild like rock stars who smash guitars / Poison bars from the Gods bust holes in your mirage" — Inspectah Deck, "Above the Clouds feat. Gang Starr"

—

All is not always what it appears to be. In pursuit of compounders, investors may find themselves drawn to businesses that seem promising but are little more than mirages, companies veiled with an attractive shimmer of heat. A few ostensibly promising signals that should be viewed with caution include high earnings per share, spending cuts, and certain acquisitions.

Earnings per share

The net profit a company earns, divided by the number of outstanding common shares, is often presumed to be a useful way to value a business. While correct, hunters of compounders must view such figures warily. Compounders focus on high-quality, sustainable growth, even if that means forgoing steeper short-term growth. High earnings per share (EPS) may seem like an indication of company strength, but it's a metric that can appear impressive without long-term value being built. The risk is that management is acting with short-term interests in mind, focusing on meeting quarterly goals rather than driving enduring growth.

Spending cuts

A focus on near-term goals can also show up in spending cuts, particularly advertising and promotion, or research and development. The former can amount to "brand abuse," harming a business's recognizability and strength. While such maneuvers may improve profitability in the short-term and suggest fiscally responsible management, they may cripple a business's enduring prospects.

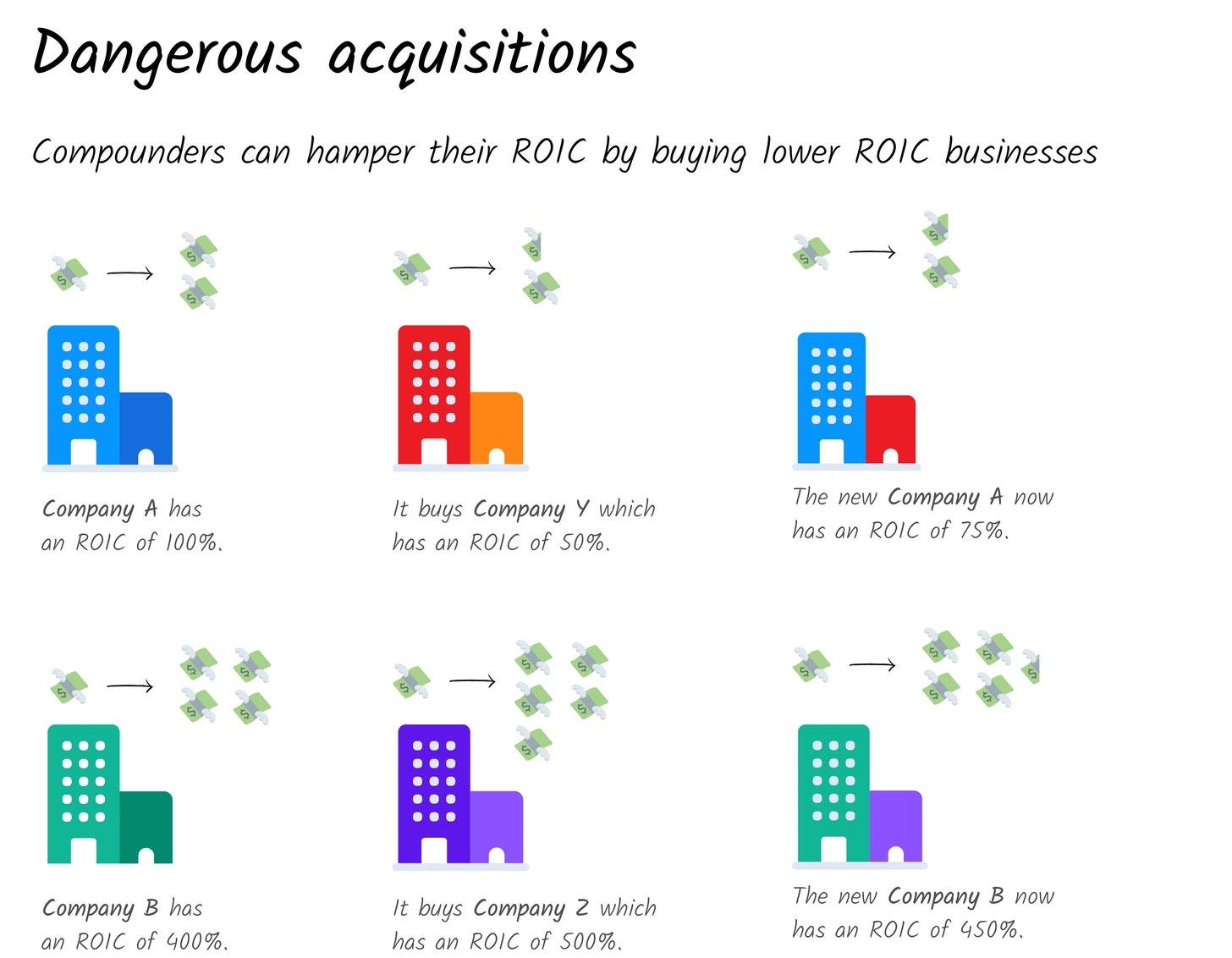

Low ROIC acquisitions

We spoke of how compounders can use their free cash flow to fund acquisitions at higher rates than competitors with a lower ROIC. This practice is not without its risks, however. If a compounder can buy or adapt an acquisition such that the purchased business reaches a similar or better ROIC, that is to the acquirer's benefit. However, the opposite can occur — a compounder may buy a company with a significantly lower ROIC. Once combined, this diminishes the strength of the aggregate entity's ability to compound. While such a purchase might seem advantageous — it might improve EPS, for example — it hampers the machine that drives growth.

~

Though there's no indication that he joined Jay-Z and Warren Buffett in sipping strawberry milkshakes that day in Omaha, Charlie Munger would have shared the two men's appreciation of compounding.

"Understanding both the power of compound interest and the difficulty of getting it is the heart and soul of understanding a lot of things," Munger once said, also noting, "The big money is not in the buying or the selling, but in the waiting."

The principle of compound interest not only drives the creation of personal wealth but propels great corporations to new heights at a sustainable rate. Those companies — the rare compounders — share characteristics that can be used to identify them. Indeed, even in their mirages, their traps, they resemble each other.

They also move in predictable patterns, going from good to great by overhauling their operations, "reloading" to attack a new market and clustering in similar spaces. We'll focus on these subjects in future editions before identifying the next generation of compounders.

Below, you’ll find some interesting resources on compounders. If you have any favorites of your own feel free to respond to this email or DM me on Twitter.

Seeking Durability, Polen Capital

Standing the Test of Time, Polen Capital

The Equity "Compounders", Morgan Stanley

Podcast: Value Investing with Legends, Polen Capital

Seeking Capital Appreciation Through Business Value Compounders, Artisan Partners

Daniel Loeb Adds Opportunistically to 3 Compounders, GuruFocus

Podcast: The Multi-Faceted Future of Value Investing with Henry Ellenbogen and Anouk Dey