Actionable insights

If you only have a couple minutes to spare, here’s what investors, operators, and founders can learn from Harvard, as a media company.

There are different paths to success. The Harvard Business Review (HBR) was founded in 1922 and struggled to breakeven for more than 25 years. Today, it’s one of the world’s most impactful media organizations.

Media can turn expenses into revenue. Plenty of businesses devote time to content marketing. But by building a media arm worth paying for, companies are able to turn marketing expenses into a revenue stream.

The next HBR could be built by a startup. Edtech companies and fundraising platforms look well-positioned to run the Harvard playbook and create a durable, valuable media arm.

Adapt or die. HBR adapted its content and form multiple times over its history to appeal to contemporary readers. It did so while preserving its foundational value.

Harvard Business School is a bigger media company than Forbes.

Though best known as a home for higher learning, America’s most prestigious scholarly institution is sneakily, surreptitiously also a publisher par excellence with financials to match.

Since its founding in 1922, the Harvard Business Review (HBR) has become a defining voice in the media landscape, bolstering the authority and reputation of its parent organization, while simultaneously bringing in hundreds of millions in revenue.

It begs the question: is Harvard Business School a media company in disguise? And if it is, who else might unknowingly be a publisher, wrapped in another business?

We’ll interrogate these questions in today’s piece. In particular, we’ll touch on:

HBR’s long road to success.

How the Review compares to other publishers.

The case for Harvard as a media company.

Other media empires in the making.

Let’s begin.

History: A Slow Burn

Arch Shaw thought it was a terrible idea. Five dollars? Five?

No one would pay that much for a magazine, he was certain. Especially one designed to bring business knowledge to the masses.

Wallace Donham, Dean of Harvard Business School, had reason to trust Shaw. Not only had the Michigan native made his name in the media industry, he’d done so in business. Founded in 1900, Shaw’s Spectrum was known as “the magazine for business” and boasted a robust readership. It didn’t hurt that he’d both attended and lectured at Harvard in the years since.

Those qualities had convinced Donham to make Shaw the official printer for his new initiative: the 1922 launch of the Harvard Business Review. But the two men had reached an impasse — precisely the sort that would be covered by the publication in years to come — before it had gotten off the ground: pricing.

In the end, the Dean won out, convincing Shaw to stay on as publisher despite their differing viewpoints. Though Donham agreed that $5 was a premium for an annual subscription ($81.42 today), he believed HBR would merit it. After all, who else was opening up the school’s incipient “case methodology” for public consumption?

So ended the first strategic quandary of HBR — solved through intuition rather than incisive research.

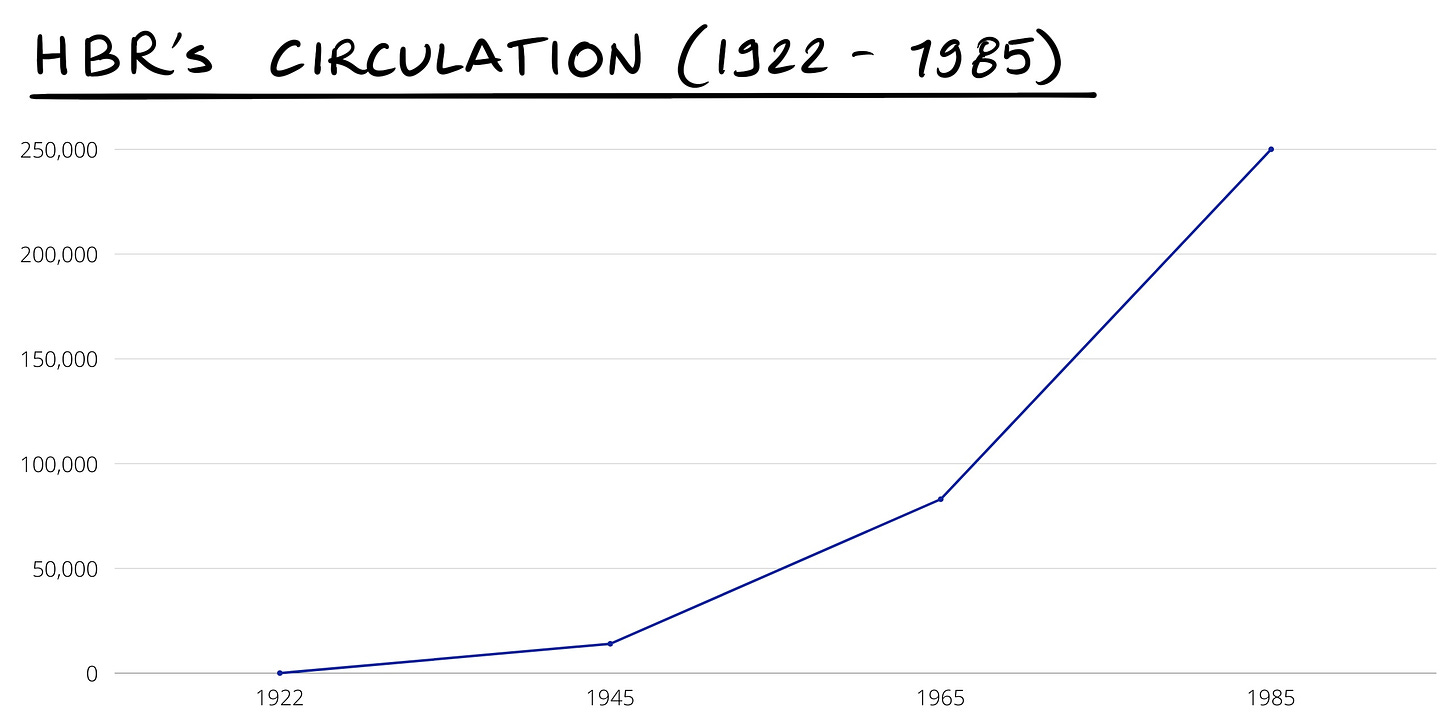

Over the following years, the wisdom of Donham’s decision would be called into question. By 1945, HBR had racked up just 14,000 subscribers, a rate of 600 new customers a year. Unsurprisingly then, the publication struggled to keep the lights on.

That wasn’t to say the offering wasn’t valuable or influential. Indeed, even at a small circulation, HBR showed a willingness to talk about business issues with real impact. In 1935, for example, one piece highlighted the role of women in the workplace. In tandem with such topics, theorists like Donham used the Review’s pages to advance their views on management, contributing to an increasingly sophisticated field.

The acuity and rigor of the product paid off in the aftermath of World War II. With the US economy undergoing hypergrowth, and consumer culture entering the foreground, HBR was well-positioned to serve a budding generation of business leaders set on finding fortune.

By 1965, HBR’s circulation had reached 83,000 and by 1985, the magazine reached nearly a quarter of a million readers.

Though its influence swelled, the core of HBR’s offering stayed the same during this period. While Donham had been wrong to price the product at such a premium, his instinct about the value of case studies had been dead on.

Ted Levitt would help modernize that premise. Joining as editor-in-chief in 1985, the marketing professor helped create the foundations for the HBR we see today, eschewing the drab design borrowed from academia in favor of a slick, consumer-friendly offering. That was coupled with a sense of fun with cartoons adorning pages, and increasingly provocative pieces taking center stage. One particularly controversial piece argued that women in the workplace should be treated differently depending on whether or not they were parents — a view with which many disagreed.

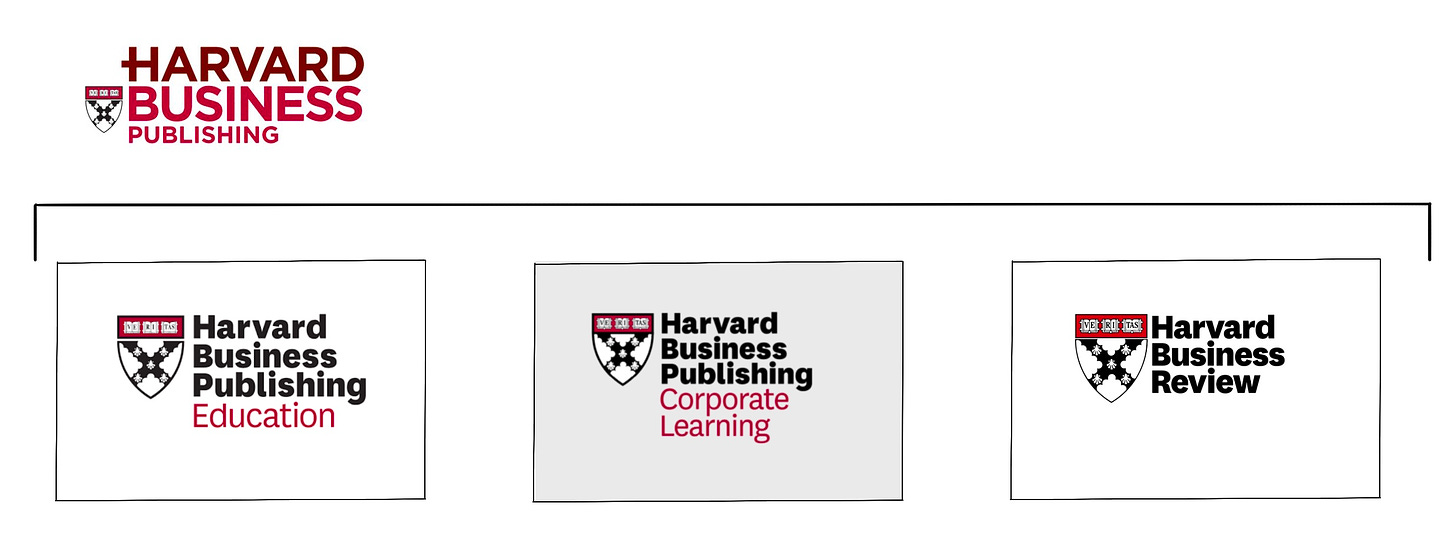

In spite (or because) of such controversy, HBR continued to grow. Its next significant change arrived in 1994, as Harvard Business formed Harvard Business Publishing (HBP) to house its media activities. This supra-division included HBR, book publishing, seminars, and other related activities, and was wholly owned by the university.

The advent of the tech revolution prompted HBR’s most recent reinvention. Starting in 2010, the publication began to embrace more current topics of conversation as well as new modalities. Though one editor famously proclaimed “HBR will not blog” in 2004, it did eventually begin to publish its work online. That process was managed by Adi Ignatius who remains in his role as Editor in Chief.

Today, HBR cuts an unusual figure in the media landscape. Though well-known and respected, it often feels overshadowed by younger and buzzier offerings. As we’ll discuss, the numbers suggest HBR is not to be underestimated.

The Modern HBR: A Media Empire

As alluded to, the Review is just one component sitting beneath the HBP umbrella. It is joined by online courses, curricula available for purchase, “podcases,” and even simulations (essentially business-themed games). These products are housed under three categories: “Higher Education,” “Corporate Learning,” and the “Harvard Business Review Group.”

This organization gives fitting credence to HBR’s leading role. With 340,000 annual magazine subscribers and 8.5 million - 10 million monthly web visitors, the Review is the clear star product. That’s been aided by its own product development.

Specifically, HBP has developed the Review into a true multi-media machine. Visitors to HBR.org can find short-form articles, long-form think pieces, videos, a series of podcasts, a “visual library,” seminars, a store, and more. Newer mediums show particular vitality, supporting younger, fresher voices. Of course, these products are joined by HBR’s original incarnation, a physical magazine.

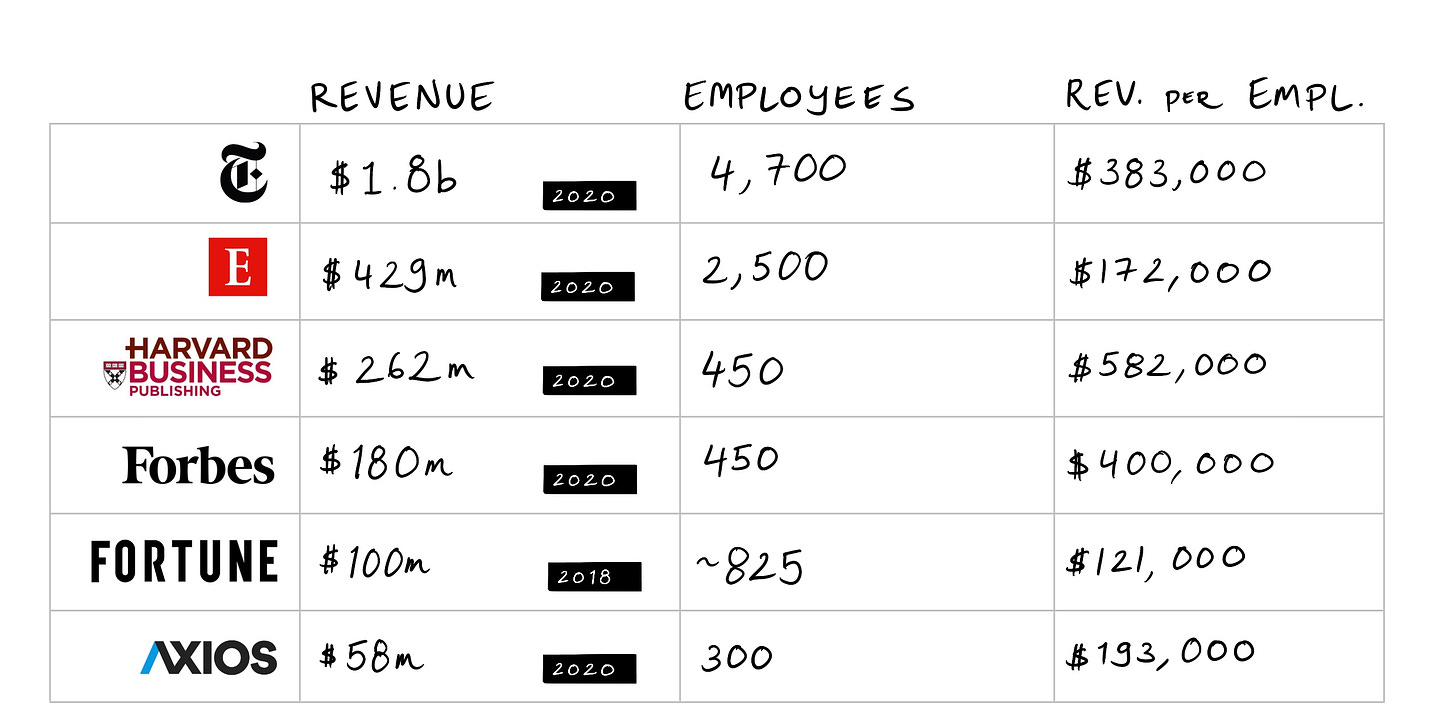

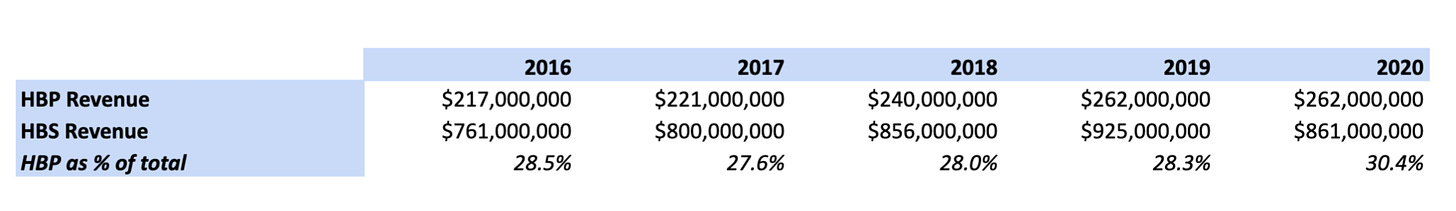

The offering appears to be working. In 2020, Harvard Business Publishing brought in $262 million in revenue, flat from the year prior. Though disappointing in isolation, that unglamorous performance looks much better when compared to the beatings many other media outlets suffered during the coronavirus lockdown. Over a five year period, revenue grew at a 3.8% CAGR.

HBP’s figures put the organization within the orbit of luminaries like The Economist while simultaneously positioning peers like Forbes, Fortune, Axios, and others in the rearview mirror. Remarkably, HBP has managed this with a considerably leaner staff, employing just 450. That gives it much better leverage than other organizations.

It’s worth adding that the NYT is currently valued at close to $8.2 billion, 4.5x of last year’s revenue. If HBP were a public, for-profit organization traded on equivalent multiples, it would be valued at $1.2 billion.

Credit should be given to Adi Ignatius for HBP’s performance, but of course much is owed to its business model. Like few others, HBR has nailed a “make once, sell infinitely” approach. Case studies and courses are able to command a high price (can you imagine spending $18 for a single NYT article?), require little to no added maintenance, and are of effectively evergreen relevance. While most media companies struggle to monetize their backlog, HBR’s continues to earn.

From a rather inauspicious beginning, HBP have landed on a powerful business model going from strength to strength. Its success may provoke its parent entity to entertain more existential questions.

Harvard: The Consequences of Redefinition

Is Harvard a media company?

Before we can answer that question, we must first manage something rather trickier — defining what a “media company” is.

That query is one debated by academics and operators with varying levels of complexity. Some will point to the distribution of content as the salient characteristic, others, the creation. The best, not-perfect-but-good-enough definition I can come up with is as follows:

A media company is an organization that directly makes money by creating and distributing content for an audience, at a reliable, regular cadence.

Is a company blog a media company? No. Not if it doesn’t earn money in its own right, directly. Are social media companies also media companies? Not unless they begin to create their own content. Is a novelist a media company? Only if they publish at a reliable, regular cadence.

This description will not withstand too much scrutiny; each element can be picked apart. But I think it does a sufficiently solid job of excluding critical edge cases, and more importantly, is no less flawed than other options.

So, by this categorization, is Harvard — and specifically, Harvard Business School — a media business?

Via its publishing arm, Harvard certainly has a vehicle that makes money by putting out analysis to a large audience, frequently. Interestingly, this subsidiary seems to be an increasingly significant part of the larger organization with HBP driving 30% of all business school revenue, a figure that rose during the pandemic. As noted earlier, a public market investor might value HBP north of $1 billion, a figure that looks significant, even when placed next to the business school’s $4 billion endowment.

Perhaps a better question is, what benefit does Harvard receive by thinking of itself through this lens? What can reconceptualization unlock?

Above all, scale without brand dilution.

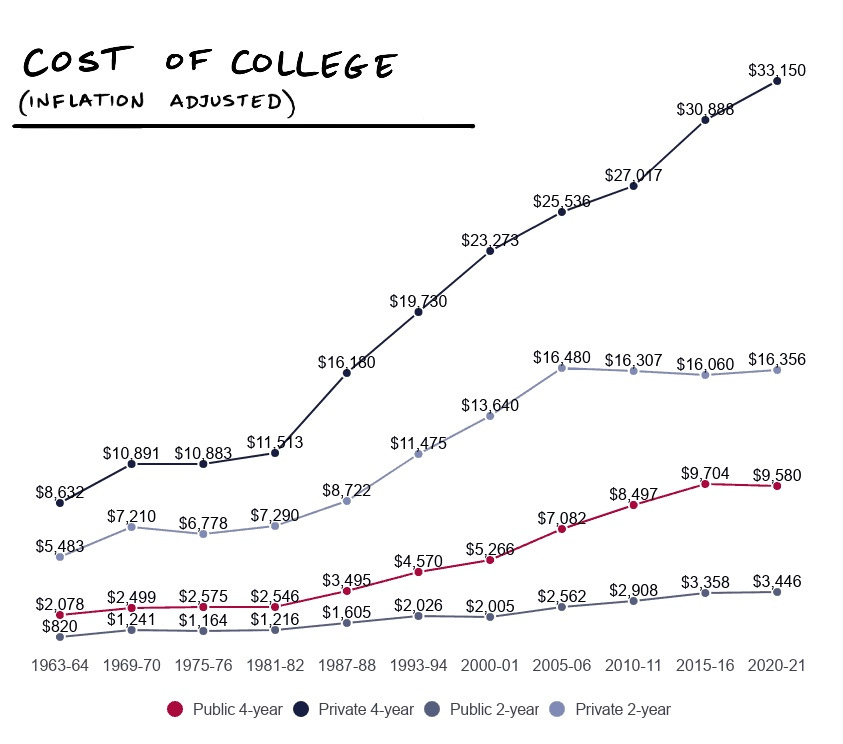

In some respects, this is the holy grail of institutes of higher learning: earning more without actually accepting more (and losing their rarified luster). Over the past forty years, most universities seem to have solved this problem by radically increasing pricing — a move that both relies on and fortifies brand power. (There’s a sort of tautology here: Harvard is worth $250,000 because it’s Harvard, and it’s Harvard because, in part, it costs $250,000.)

This cannot continue indefinitely though, particularly in a world that seems more volatile. Paying a cool quarter-million for a degree delivered in person is one thing; doing so for a Zoom room surely makes even the most affluent balk. Without continuing to increase pricing, what options do schools like Harvard have to scale without diluting their own brands?

Arguably, media presents the best opportunity. It is both extensible and, if done correctly, reputation enhancing; few could convincingly argue that HBR has not been a magnificent advertisement for its parent. It is also well-suited to scholastic environs. Though HBR draws its contributors from many institutions, corporations, and backgrounds, it benefits from having a sterling faculty to draw upon.

What would HBS look like if it began to act like a media company? What could it do?

Opportunities abound. For one thing, HBR’s offering is still very focused on general business. Content is broad in scope, though the publication has made efforts to expand its coverage of DEI initiatives. It’s easy to imagine a future in which HBR segments further, moving horizontally to cover different sectors explicitly. Should there be a tech-centric offering? An AI-focused sub-publication? A CPG weekly?

To test out this concept, HBR could borrow from its podcasting model and embrace external talent. Distinct newsletters could be helmed by experts and creators that meet Harvard’s quality bar but bring greater freshness and ingenuity to the form. Given Harvard’s brand power, the Review should have the ability to draw some exceptional names. What if an HBR Crypto newsletter was managed by Paradigm’s Dan Robinson? Or its gaming publication starred Matthew Ball?

As other media companies duke it out to woo elite creators, Harvard’s position as an educational institution may offer unique allure.

Beyond segmenting and leaning into the creator movement, it would be exciting to see HBR experiment with novel formats. For example, what would an AMA product look like on the Review? Able to draw exceptional business leaders and a sophisticated audience, the crowdsourced Q&A format on HBR could be unique.

Could this, in turn, herald a more open, engaged member’s only community? Though it would bring complexities, particularly with regard to moderation, a modern HBR forum could be an intriguing experiment. Part user-generated platform, part professional network, such an addition could give HBR a way to gather more information on its audience, offer greater value, and upsell its readership.

These suggestions are just the tip of the iceberg. Across writing, podcasts, and video, HBR has room to be much more aggressive; permission that has to come from the top.

With so impressive a publishing entity under its auspices, a reimagination of Harvard could create extraordinary, outsized value. But institutions move slowly and are loathe to change; Harvard is unlikely to ever think of itself as a media company. That presents an opportunity for a wave of well-positioned businesses to capitalize.

The Next HBR: Sneaky Media Businesses

In “Whose Story Wins?” we surveyed the state of “soft power” in tech, concluding that few organizations have truly understood the potential of owning and exercising a narrative, via media. Robinhood, Andreessen Horowitz, and Stripe are among an elite few.

Perhaps partially because of that, it feels like there’s still an opportunity for someone to build “HBR 2.0” — a subsidiary that extends an existing brand by providing deep, definitive business analysis. It’s worth noting that succeeding in such an endeavor is not only potentially financially beneficial, nor is it just a reputational benefit. Rather, it represents that niftiest of business tricks: the transformation of cost into revenue. Instead of spending money on performance marketing or sponsorships, organizations can earn by selling themselves, and the content produced under their banner.

Such a prize is worth fighting for. Those best-positioned include insurgent edtech startups, fundraising platforms, and venture funds.

Edtech

HBR’s successor may come from the same sector: education. Just as Harvard leveraged its intellectual reputation to build a publisher, modern edtechs focused on business may seek to do the same.

Of those, Reforge is arguably best positioned. Though narrowly focused on growth, the company has established itself as an impressive educator, attracting many medium-to-high level tech workers, and earning a favorable reputation. It’s easy to envision a “Reforge Growth Review” spinning out of that, with content sufficiently valuable to merit payment. A Reforge blog provides a rough foundation for a much more ambitious push.

On Deck may be able to attempt this move, too. Though its broader scope may complicate matters, the cohort-based course company has succeeded in creating a brand known by most in the industry, and trusted by many. Compared to Reforge, On Deck seems to attract a slightly younger and more junior customer base, and caters to a variety of different interests from podcasting to product, angel investing to longevity.

Still, a successful general business publication seems plausible, and would fit the company’s stated aim of becoming the “Stanford of the internet.” Perhaps it can become the HBR, too.

Fundraising platforms

Though seeking a different end, fundraising platforms look equally capable of producing a strong tech and business publication. Not only do companies like AngelList and Republic have good reputations (and seem to be expanding quickly as private investment markets boom), but both should boast access to unique, relevant data.

This is likely particularly true of AngelList, given the company’s long history. Since launching in 2010, Naval Ravikant’s platform has operated as an informal hub for off-piste venture financing, involving firms, angel investors, founders, and operators. It could draw on more than a decade of data to augment its stories.

There’s also a clear, virtuous tie-in for these platforms: by telling the tales of exceptional businesses, readers are likely to find themselves persuaded to invest in future opportunities, handled on AngelList or Republic’s platform. There may be legal ramifications of directly tethering these two functions, but even an oblique link could prove powerful.

Owning the narrative engine for private financing and the platform on which such transactions are conducted would represent a potent combination.

Venture capital

Of course, at least one venture firm has explicitly staked out a claim as the new HBR: First Round, the fund behind the “First Round Review.”

In almost all respects, FRR feels spiritually aligned with HBR. It embodies an elegant, minimalist aesthetic, features high-quality writing, and often focuses on case-study-style practitioner stories. If someone were seeking to build a tech-focused HBR from scratch today, it would, in all likelihood, look a lot like First Round’s creation.

Unlike Harvard, First Round doesn’t charge for its publication, though it may still meet our definition of a “media company” in that certain deals could perhaps be linked to FRR, which in time, make the fund money. It is certainly more tenuous, and closer to content marketing, not that it should matter to the firm.

As discussed in the soft power piece, a16z has also made a play in the space, though the focus of “Future” feels more abstract. In that respect, it seems less of a successor to HBR than a reincarnation of an actual academic journal; heady ideas and formulations rather than tactics and takeaways.

Beyond these two firms, it’s hard to identify others that are exceptionally well-poised to create an iconic publisher. That doesn’t mean an insurgent couldn’t catch up; the incipience reflects that we are still in the early days of comprehensive tech coverage.

To avoid competing head-to-head with a16z or First Round, firms may seek alternatives. One avenue might be for a coalition of funds to create a shared “Venture Business Review.” Though such a manifestation wouldn’t give as much brand value to a single firm, it would present an opportunity for funds to build shared distribution, benefit from shared expertise, and present a publication that feels further from content marketing. Of course, coordination would be more difficult and it’s easy to imagine how cross-firm politics might meddle in matters.

Crypto funds may also want to get in on the action, dedicating serious resources to media efforts ahead of mainstream adoption. What would a Paradigm Crypto Review or a Multicoin Review look like? Accessible case studies could prove an effective way to spread the sector’s gospel and highlight the impact of new projects. Though several excellent crypto media outlets and research firms exist, there’s room for a slower, more deliberate offering.

“A diamond is just a lump of coal that stuck to its job.”

Though those words are attributed to Malcolm Forbes, one-time steward of the eponymous magazine, they feel particularly well-suited to the Harvard Business Review and the school’s broader publishing arm. From modest beginnings in 1922, HBR has taken the long path to brilliance, reinventing itself frequently, but preserving what makes it special.

In that respect, it represents a different, rarely-seen value creation story: the academic spin-out that challenges the supremacy of its parent organization. Not only does that make it worthy of the kind of thoughtful study the publication popularized, but an intriguing model for a wave of content marketers on the cusp of maturation.

The Generalist’s work is provided for informational purposes only and should not be construed as legal, business, investment, or tax advice. You should always do your own research and consult advisors on these subjects. Our work may feature entities in which Generalist Capital, LLC or the author has invested.