How to Raise From Institutional LPs

The definitive tactical guide to winning over endowments, foundations, and more.

🌟 Hey there! This is a subscriber-only edition of our premium newsletter designed to make you a better investor, founder, and technologist. Members get access to the strategies, tactics, and wisdom of exceptional investors and founders. Become a member today.

Friends,

In 1985, a 31-year-old Wall Street banker chose to take an 80% pay cut.

This would be an unusual choice today, but it was especially bewildering amid the hyper-macho excesses of the 1980s. This was the era of Michael Milken and Henry Kravis, of junk bonds and power suits, of barbarians at the gate and “greed is good,” of Masters of the Universe and Big Swinging D*cks, of John Gutfruend’s liar’s poker and his famous directive: “One hand, one million dollars, no tears.” It was the Rome of Nero or Caligula; only the emperors wore bright suspenders and Winchester shirts.

All of these factors made the young David Swensen’s decision more conspicuous. Instead of continuing his career as a senior vice president at Lehman Brothers, the economics PhD elected to return to his alma mater, Yale University, to take stewardship of its $1.3 billion endowment. It represented a risk for the Ivy League institution as well as Swensen. Though the spirited Midwesterner had already left a mark on Wall Street, helping to structure the first-ever currency swap, he had no genuine investment experience.

Over the next 36 years, until his death in 2021, David Swensen established himself as one of the greatest investors of all time, changing how endowments managed their capital and revolutionizing modern portfolio theory. Just two months after his passing, Yale reported Swensen had produced $57.6 billion in investment gains, delivering annualized returns of 13.6%. While $1 invested in the S&P 500 would have grown to $50 over Swensen’s tenure, $1 invested in Yale’s endowment would have been worth $103.

In the process, Swensen reshaped the venture capital industry, backing early fund managers. Yale’s outlier performance subsequently persuaded other endowments to follow suit, bringing tens of billions of dollars of investment into the asset class and galvanizing the more mature industry we see today.

University endowments and other large institutional investors have become critical players in the venture ecosystem, providing professional and patient capital. For many venture managers, receiving investment from Yale, Duke, Stanford, or the University of Texas not only tops up the coffers but also marks a turning point. An investor capable of wooing Columbia and CalPERS is understood to be a serious person, a trustworthy steward, and, hopefully, an exceptional capital allocator. Securing just one of these names, or others like them, serves as powerful social proof for other LPs, smoothing fundraises.

Though many top endowments and foundations allocate to venture, the process by which they do so is opaque. For a new manager trying to break into this capital pool, it can be difficult to know who to reach out to, what kind of questions to expect, and how they make decisions. As with so many aspects of the venture craft, the secrets and strategies are locked in the heads of a small number of practitioners who have made it through the institutional gauntlet and emerged with funding.

Today’s guide brings those lessons into the light. We’ve spent months researching this subject, conducting dedicated interviews with 20 venture investors, and reviewing institutional reports. The result is the definitive guide on raising from big institutional investors, accompanied by a database of target LPs. For fund managers looking to up their institutional game, the best practices shared in this guide should save you time, accelerate your learning, and give you the best chance of winning over professional LPs.

What you’ll get in this guide

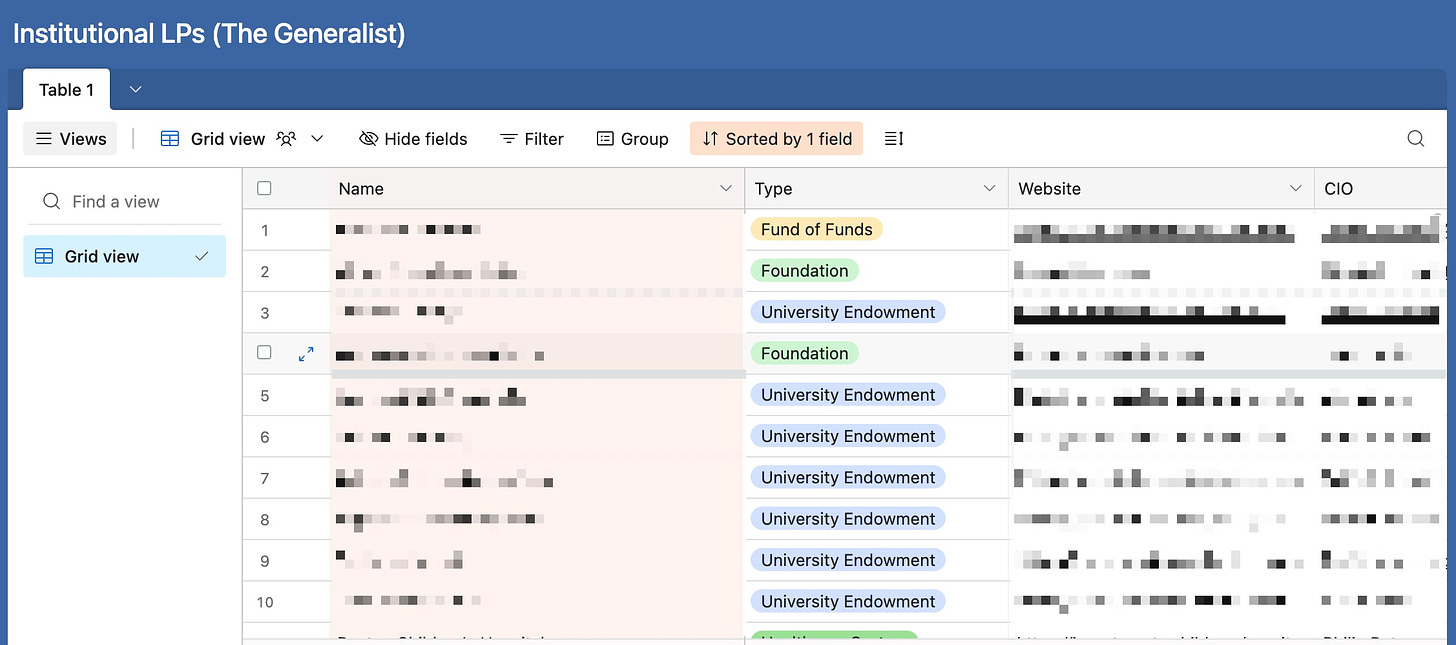

A database of 145 institutional LPs to target (and counting!)

6 essential steps to find, convince, and close institutions

17 sub-strategies to save you time and maximize your chances of success

20 outstanding investors’ advice, insights, and best practices

7 pieces of collateral you should prepare, from investment memos to a “value-add tracker”

17 portfolio construction questions you might be asked

24 vital considerations for your fund’s long-term future

Brought to you by Mercury

If Jony Ive built a banking* experience…

I think it would look a lot like Mercury. The Generalist has been a Mercury customer for years, and I’m constantly awed by the platform’s beauty, thoughtfulness, and power. It’s become a core part of how we run our business and is probably the only banking product I find a genuine pleasure to use.

Mercury’s banking experience isn’t just loved by The Generalist. 200K other startups trust it to simplify their finances and power essential workflows, like paying bills or sending invoices. By using Mercury, customers save time, get granular visibility into their finances, and have finer-toothed control over money movement.

Apply in minutes today at mercury.com to simplify your finances and perform at your best.

*Mercury is a financial technology company, not a bank. Banking services provided by Choice Financial Group and Evolve Bank & Trust®; Members FDIC.

How to Raise From Institutional LPs

Anyone who has studied the venture capital industry knows the names of its great practitioners and major players. However, even VC obsessives may not be familiar with the LPs behind the storied firms, backing them with long-term capital.

Behind luminaries like Reid Hoffman, Vinod Khosla, Roelof Botha, Peter Thiel, Mike Speiser, and Chris Dixon sit the Chief Investment Officers of multi-billion dollar endowments, foundations, and sovereign wealth funds.

Though these individuals are not the only LPs backing Tier 1 funds, they are among the most influential and discerning. They include CIOs like Matt Mendelsohn, Swensen’s successor at Yale; Rob Wallace, the leader of Stanford Management Company; the Ford Foundation’s Eric Doppstadt; and Rohit Siphaimalani, the decision-maker at Temasek, a Singaporean sovereign wealth fund. Though these names may be less well-known in tech circles, they are vital players in the ecosystem.

How can venture managers court and close the stewards of these institutions and others like them? Today, we’ll walk through six steps and outline 17 key strategies:

1. Know who you’re pitching

What is an “institutional” LP?

Key traits of the segment

2. Start before you have to

Lines, not dots

Ongoing, not episodic

Proactively build collateral

3. Prepare for a different process

Master the prerequisites

Know your 20-year story

Upgrade your back office

Ready your references

4. Make the connection

A private database of 145 LPs

Use your network

Build a magnet

Don’t ignore the juniors

5. Qualify the lead

Ask for their check size

Find your bucket

Gauge the timing

Try an anti-sell

Outline the path to a “yes”

6. Drive to a close

Protect the “yes”

Make a “no” a “not yet”

Thank you to Ann Miura-Ko (Floodgate), Aydin Senkut (Felicis), Ben Sun (Primary), Charles Hudson (Precursor Ventures), Charley Ma (Exponent Founders), Edith Yeung (Race Capital), George Rzepecki (Raba), Hernan Kazah (Kaszek), Jesse Walden (Variant Fund), Kanyi Maqubela (Kindred), Kirsten Green (Forerunner), Lauren Kolodny (Acrew Capital), Logan Bartlett (Redpoint), Michael Dempsey (Compound), Nathan Benaich (Air Street), Nikhil Basu-Trivedi (Footwork), Niki Scevak (Blackbird), Rex Woodbury (Daybreak), Zavain Dar (Dimension), Zoe Weinberg (Ex/ante) for sharing their insights for this issue of the Investors Guide series.

1: Know who you’re pitching

Few words are as frustratingly vague as “institution,” a term used to describe anything from a place of higher learning to a government body. Before successfully convincing these well-moneyed organizations to invest in your fund, you must understand what they are, how they operate as LPs, and the primary tradeoffs.

What is an institutional LP?

When VCs refer to “institutional LPs,” they are generally referring to a class of professional investors managing large sums of capital over long time horizons. Though there’s no perfect delineation, the following LP types are typically considered “institutional”:

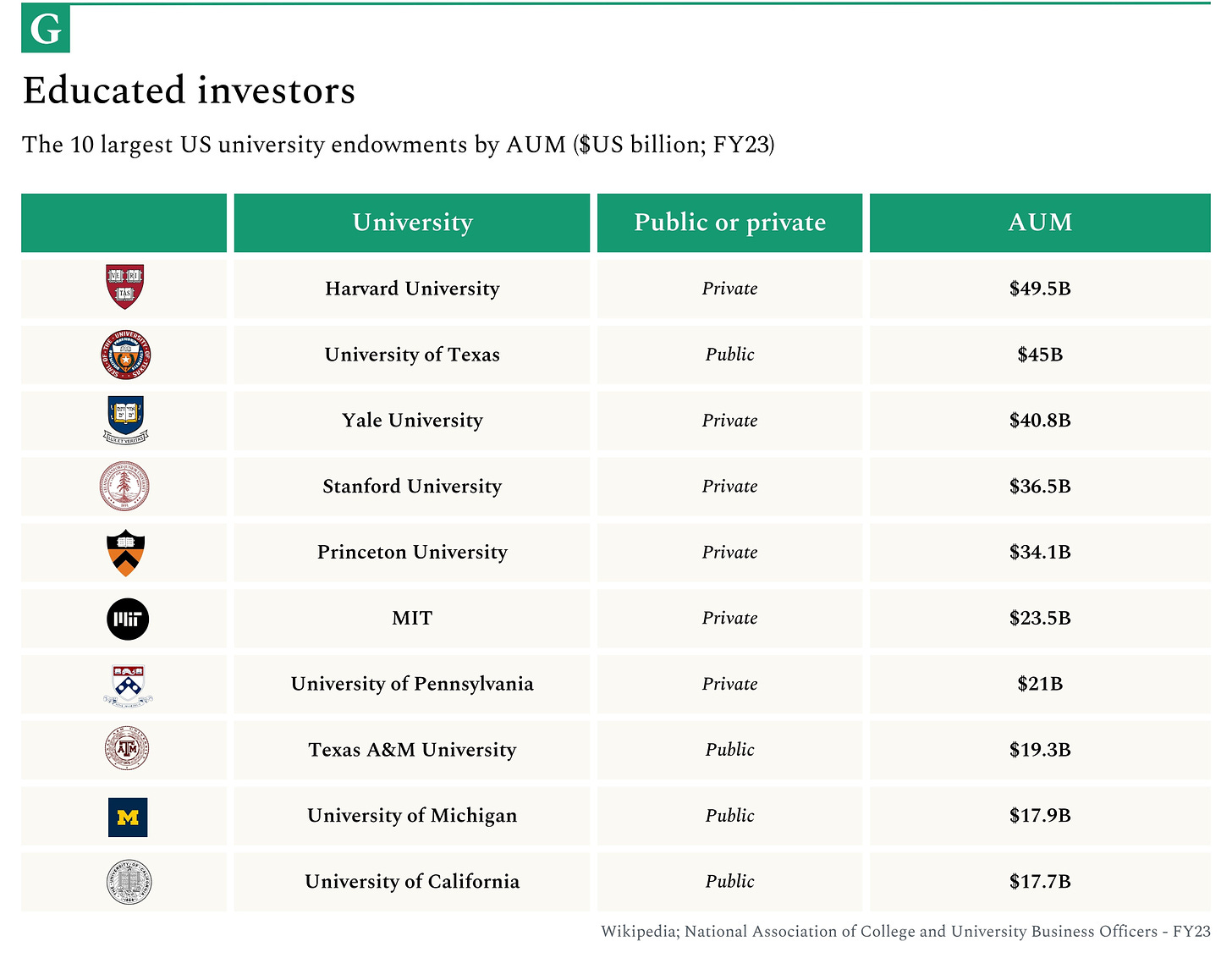

University endowments. American universities have become big players in the VC ecosystem, deploying billions of dollars a year to the asset class. Prominent examples include Duke, Yale, and the University of Michigan.

Philanthropic foundations. As well as engaging in charitable activities, foundations look to grow their capital through investments. The Ford Foundation, The Grantham Foundation, and The Rockefeller Foundation all invest in venture capital, for example.

Sovereign wealth funds. Nationally sponsored vehicles like Temasek and GIC (both from Singapore) invest in venture firms and sometimes take direct stakes. In addition to Singapore, Saudi Arabia and the UAE are frequent VC backers.

Retirement funds. Both private and public organizations run pension funds that manage large assets and invest in venture capital. Notable examples include CalPERS, CalSTRs, and Citigroup Pension Fund.

Healthcare systems. Review Sequoia’s LPs and you might be surprised to find the Boston Children’s Hospital listed. In fact, a number of healthcare systems invest in venture funds, including the Cleveland Clinic and NewYork-Presbyterian.

Multi-family offices. In many respects, family offices deserve a category of their own. Some operate as extensions of a high net-worth individual and are highly idiosyncratic. However, many large family offices (especially multi-family offices) operate extremely professionally, much like the other institutions on this list.

Fund of funds. Unlike the other entries, a fund of funds is not the source of the capital it invests. Rather, “FoFs” raise capital from LPs – including those mentioned above – and invest it on their behalf. They act similarly to other institutions, however, and are best included here.

This isn’t an exhaustive list, just an enumeration of the most common players. Large insurance companies occasionally invest in venture funds, as do other corporations. As we’ll discuss, whatever an organization’s focus, institutional LPs share essential characteristics that differentiate them.

Key traits

Though it sounds prestigious to count Stanford as a backer, not every fund is a good fit for institutional LPs. Before wasting your time, consider how your practice aligns with the key traits of this LP profile:

Writes large minimum checks

Requires a long sales process

Builds long-term relationships

Conducts rigorous due diligence

Requires high-caliber infrastructure

Large minimum checks

Though a high net-worth investor might slide in with a $25K or $250K check, most institutions want to deploy a minimum of $5 million and often more.

Kaszek

Institutions typically have a minimum check size. So if you go to a large institution and offer them a million dollars in allocation, it will not work. You need to ensure that you can offer them something that is compelling but not be too dependent on them.

– Hernan Kazah

Even if you do have a fund that’s large enough to support institutional check sizes, you may want to think about the implications for your LP base.

If you want a diversified list of backers, including institutions may prove difficult. However, if you prefer to have a smaller number of close relationships, working with LPs may prove ideal.