Kavak: The Drive to Conquer

The $8.7 billion used car marketplace became Mexico’s first unicorn by focusing on data. Next stop: the rest of the world.

Actionable insights

If you only have a couple of minutes to spare, here's what investors, operators, and founders should know about Kavak.

Kavak is a full-stack car marketplace. It handles buying, selling, and financing vehicles from end to end. Its success is thanks to its impressive data capabilities, logistical expertise, and customer obsession.

It has benefited from a fractured Latin American market. The regional market is highly fragmented, with no company holding even a 1% share. Transactions are often peer-to-peer, increasing the potential for fraud.

Financing arm Kavak Capital makes car ownership accessible. While leasing a car is common in the United States, it is often unavailable in Latam. By offering affordable financing, Kavak Capital helps many consumers buy their first vehicle. Car ownership improves a broad range of economic and social outcomes.

Kavak’s model is capital intensive. The company buys and renovates cars. Its product relies on manual labor, physical space, and real-world logistics. Scaling supply and reach takes meaningful capital.

Carlos García is a generational founder. Few entrepreneurs receive reviews as positive as García. Investors rave about the CEO’s ability to balance an aggressive vision with an eye for detail. He has built a strong leadership team and culture of ownership.

In the heart of the Amazon jungle lie the ruins of Fordlandia. Once-pretty homes stand empty, their gardens overrun by shrubs. Machinery, once operated by dozens of men and women, blooms with rust. The windows of their workplace, a broad factory, offer nosy visitors a grimy, gap-toothed grin.

It had gone wrong for Henry Ford almost from the start. Frustrated by rising prices for Sri Lankan rubber, the industrialist decided on an unorthodox solution. Rather than bartering the British-held monopoly, he would extend his supply chain, developing a plant in the middle of the Brazilian rainforest. What better place could there be to produce rubber than its native land?

Though Ford’s plan had pragmatic motivation, it was also propelled by loftier ambitions. Since conquering the business world, the magnate believed his destiny was to apply his methodology to society at large. An attempt to construct an industrial city to rival Detroit in Muscle Shoals, Alabama, had failed, but he saw a blank canvas in the Amazon. Unpolluted by the pesky political intrigues that had shuttered his previous project, he could build a city in his image: Fordlandia.

His first mistake was the price. In 1928, Ford’s aides paid the Brazilian state of Pará $125,000 ($2.1 million today) for more than 5,600 square miles of land. Reportedly, the laws at the time meant Ford might have gotten it for next to nothing.

Ford’s luck scarcely improved from that inauspicious start. Despite his company's high wages, it was difficult to attract manpower to work in the jungle and perhaps even trickier to transport food and building materials down a river with a seasonal tide. Supervisors came and went, and even after the skeleton of a civilization had been set – dirt streets tracing a grid between settlements – violence broke out in 1931 between Brazilian workers and expats. Much of the colony’s early work was erased, with laborers destroying equipment and defacing homes.

Though stability surprisingly followed the uprising, with Fordlandia rebuilding and adding amenities like paved roads and a dance hall, the enterprise remained doomed. As it turned out, Fordlandia failed in its most fundamental task: to produce rubber. Even an expert botanist, flown in by Ford to oversee his wretched plantlings in 1936, could not improve on a modest crop. Less than a decade later, Ford had left Fordlandia, returning ownership to the Brazilian government.

In 2021, another automobile baron entered the Brazilian market with dreams of conquest. Carlos García, founder and CEO of used car marketplace Kavak, announced his intention to invest $500 million in the country. He began in São Paulo.

Though it may not be quite as expansive as Fordlandia, “Kavak City” is an ambitious construction. Not only is it Latin America’s largest vehicle reconditioning plant but a cathedral to a new kind of consumer purchasing experience, designed to showcase the powers of Kavak’s technology. It also represents the center of García's broader Brazilian initiative, which has already expanded to Rio de Janeiro and is expected to bring Kavak branches to dozens of malls.

So far, there is no reason to think that Kavak City will go the way of Ford’s ill-fated experiment. Since launching in 2016, Carlos García and his two co-founders, sister Loreanne García and Roger Laughlin have succeeded in building a business that many consider revolutionary for its impact on the Latin American car market. They have minted Mexico’s first unicorn and laid the groundwork to become a global juggernaut, launching operations in Argentina, Brazil, Colombia, Chile, Peru, and even Turkey. If García has his way, Kavak may extend beyond the automobile, becoming a financial “super app” or “ecosystem of services,” as he described it. Given that backers describe García as a generationally gifted founder with a rare ability to balance vision with reality, that statement may be more than mere bluster.

But Kavak’s rapid growth and heady ambitions have come at a price, namely the sale of equity. The company has raised $1.6 billion in funding, with its most recent $700 million round valuing the business at $8.7 billion. The money Kavak has digested bolsters arguments that it is a capital-intensive business that cannot scale like a tech company. To some, that makes Kavak’s latest valuation untenable, particularly as public market competitors like Carvana have seen their market caps collapse by nearly 90% over the same period.

Kavak City represents both sides of the company behind it: the promise of what could be and a reminder of the capital demands of a business inextricably tied to the physical world. Time will tell whether it becomes a monument to misplaced audacity or another outpost in García's world conquest.

In today’s piece, we’ll explore these questions, covering:

Origins. The premise for Kavak first came to Carlos García on an airplane. It would take him three years to officially found the company.

Market. The Latam market was perfectly designed for a business like Kavak. Fragmentation, fraud, and a lack of financing meant there was obvious room for improvement.

Product. Kavak goes to considerable lengths to provide a good customer experience, providing home delivery for cars that have been purchased.

Leadership. Beyond the purported genius of Carlos García, Kavak has a robust team filled with talented operators. The company relies on a culture of “participatory dictatorship.”

Valuation. Publicly traded used car marketplaces have been savaged in recent months. Should Kavak need to tap further financing, its valuation may be impacted, too.

Future. Kavak’s expansion into Brazil and Turkey could be followed by moves into Saudi Arabia and the UAE. Further features may bolster García's argument that Kavak is building a “super app.”

Let’s drive.

Understand the world's most consequential companies before they IPO. Don't miss our next email.

Origins: On the road

The brokenness of used car buying, selling, and financing in Latin America could only be solved by a stubbornly focused entrepreneur. With Kavak, Carlos García has proven equal to the challenge. In many respects, he seems to have unwittingly trained to excel at the business he is building.

Starting the engine

Every entrepreneur must grow comfortable with change. From one day to the next, one moment to another, the most pressing demands may shift meaningfully. Carlos García's upbringing prepared him for such transitions. As the son of a Venezuelan military man, he and Loreanne’s childhood was filled with frequent relocations. By the age of thirty-seven, he estimated he had moved more than thirty times. That included a stint in the United States. (Much of this information comes from Cracks' excellent Spanish-language podcast.)

After receiving a degree in economics at Caracas’ Universidad Católica Andrés Bello, García uncovered his passion for launching projects. He had always had a solid worth ethic, cutting grass as a twelve-year-old to make extra money. But it was in working at food and beverage distributor Alfonzo Rivas & Cia that he experienced business at real scale. As a brand manager, García was tasked with buoying the firm’s portfolio of wines and spirits. He increased the subsidiary’s revenue by 28% during a three-year stint and established one wine as a national leader.

After attending Oxford’s Saïd Business School in 2010, García interned at Amazon and then took a job at McKinsey. It was a surprising move for a man who considered himself ambitious but unstructured. The consulting firm instilled discipline in García and brought him back to Latin America. True to the consulting stereotype, he spent much of the next two years traveling between countries, bouncing from Venezuela to Colombia to Mexico City.

Detour

In making a more permanent move, the idea for Kavak first emerged. In 2013, toward the end of his time at McKinsey, García decided to move from Bogotá to Mexico City. Though he hadn’t spent much time in Colombia’s capital given his itinerant lifestyle, he had nevertheless purchased a car. Rather than ship it north, García figured he would sell his car and buy another once he’d settled in Mexico.

Despite listing it in the classifieds and visiting dealerships, García failed to find a buyer. He left Colombia with his car unsold, sitting in a friend’s garage. In the end, it took six months for him to offload the vehicle.

Not long after that frustrating experience, García found himself sitting on a plane like so many other consultants. Instead of preparing his latest pitch deck or research report, his mind wandered back to the prolonged pain of selling his car in Bogotá. Why had it been so dreadful? Did it have to be that way?

As his wife dozed in the seat next to him, García sketched a potential solution. What if a website could make an offer on your car instantly? Instead of posting on classifieds or risking a transaction with a stranger, you’d get a fair price from a trusted source. By the time he’d landed, García had decided it was an idea he couldn’t relinquish. As he settled in Mexico City, he hired two developers in India to develop the first version of a car purchasing algorithm.

Pit stop

Life got in the way. Though he continued to putter around with his algorithm on the side, a kind of hobby, García wasn’t quite ready to commit to starting a business. Instead, he joined one. In February of 2014, García became Chief Marketplace Officer at Linio.

Founded in 2012, Linio served as Rocket Internet’s Latin American e-commerce play. The company sought to capitalize on the absence of Mercado Libre and Amazon in Mexico, using that as a launchpad to conquer other regional markets. In total, Linio would expand to eight countries, an impressive feat given the weak infrastructure on the continent. Linio built out digital payments infrastructure and a logistics network to process online purchases and deliver goods, endeavors that gave García valuable experience.

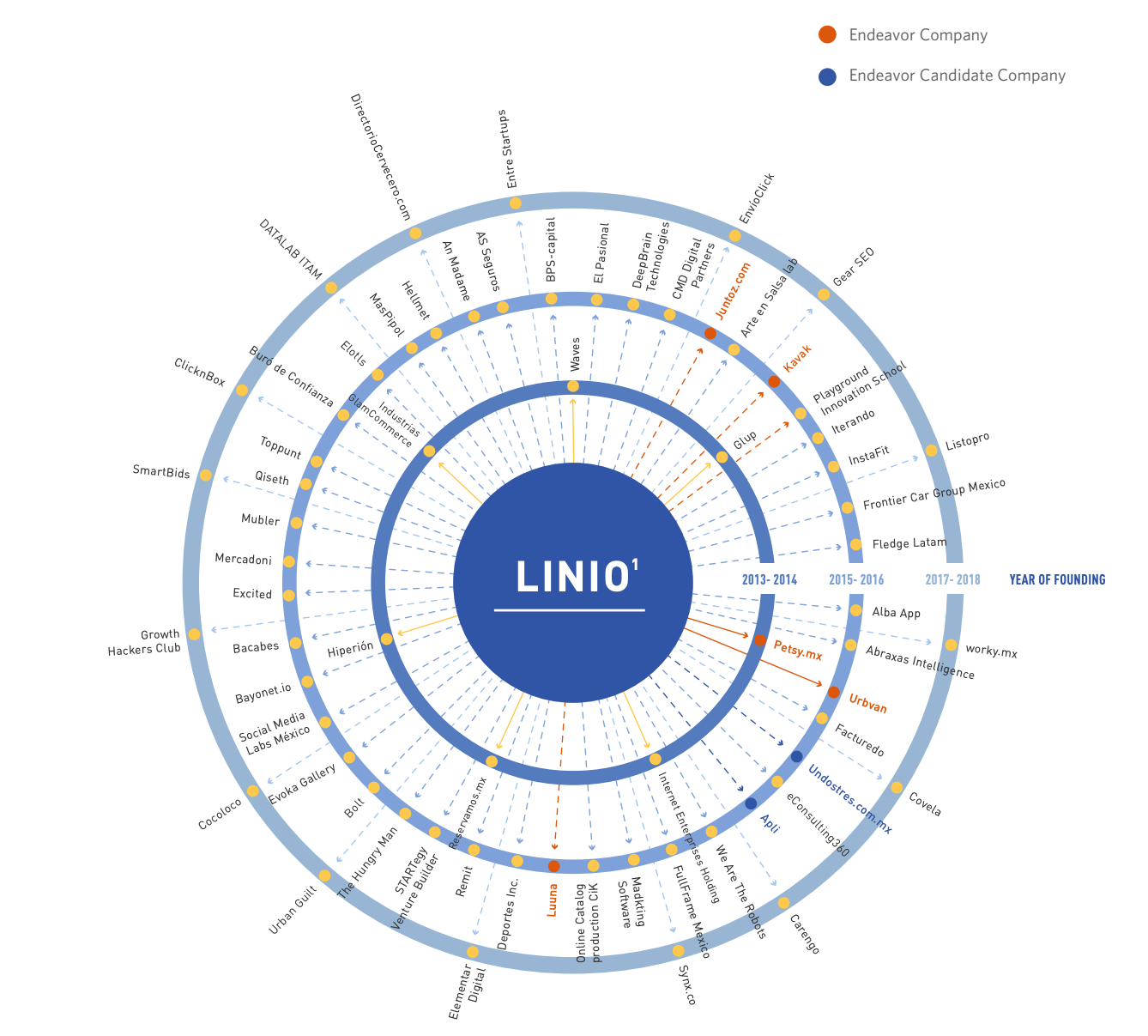

Despite its efforts, Linio failed as an enterprise. The company raised more than $230 million from investors before selling to Chilean business Falabella for $138 million in 2018. Despite its financial shortcomings, Linio buoyed the Latin American ecosystem, driving the adoption of online commerce. Even more importantly, it acted as a finishing school for local entrepreneurs. A 2019 report from Endeavor remarks that members of the “Linio Mafia" have founded at least sixty-six companies.

Linio showed García the challenges of building an online commerce business and revealed the risks of scaling too quickly. It would also deliver his co-founder, Roger Laughlin.

A fellow Venezuelan, Laughlin shared García's roots and his international upbringing, having attended American schools in Switzerland. After university in Caracas, he worked as a consultant at Bain before joining Groupon’s operations in Brazil. When the two met, he worked as a Managing Director at Linio.

Though García's side project had mostly languished during the fast-charging days at Linio, personal experiences had fortified his conviction in the importance of the problem area. As hard as it had been to sell his car in Colombia, it had been equally difficult to buy one in Mexico. Even worse, financing was almost impossible to come by. While García was financially secure enough to afford the upfront payment, surely millions of others weren’t. He realized that wasn’t just an inconvenience but a meaningful impediment to economic mobility. A car was not only a way to get from Point A to Point B; it was an asset, a form of empowerment that might increase one’s earning potential.

The more García studied the space, the more he recognized the scale of the opportunity and the serendipity of his current location. As we’ll discuss later, not only was the Latin American market particularly suited to an insurgent strategy, Mexico City was the ideal beachhead.

In the summer of 2016, García and Laughlin made their move, committing to start a business in the used car space. The pair chose an eponym that reflected their heritage: Kavak, the name of a village on the path to one of Venezuela’s great natural beauties, the tabletop mountain, Auyán-tepui. García and Laughlin were ready to climb.

Picking up speed

Though García and Laughlin had an abundance of drive, they didn’t have much money. The pair decided to build bootstrapped for the first few months of the business.

That didn’t stop them from recruiting. Thanks to García’s magnetism and their Linio bonafides, Kavak’s founders secured impressive talent for 15-20% of their market salary; some joined for nothing. Kavak’s first ever hire was compensated in food and housing, living in the “office” that occupied the fourth floor of the apartment building in which García lived.

Despite keeping a low profile, it didn’t take long for Kavak to attract investors. Former Linio colleague Carlos Salinas – now founder of the Thrasio-inspired Zebrands – introduced García to Hector Sepulveda, founder and Managing Director of Nazca Capital. Though García told the Mexican fund’s leadership that Kavak wasn’t ready to take on capital just yet, they kept calling. After a few more weeks, García agreed to provide a formal pitch. The night before the presentation, the team stayed late at the office, putting together the three-year plan for Kavak. García would later say that the company executed it almost exactly, within a 2% margin of error.

With $500,000 in commitments from friends and family, García had hoped to bring in a further $300,000 from Nazca. That would give the business a year of runway and hopefully enough traction to entice further funding. Sepulveda countered. Rather than raising just $800,000, how much money would it take for Kavak to really get up and running?

In the end, Nazca led a $3.3 million seed round in Kavak. It would prove a successful investment, though it could have been much sweeter. Nazca sold its stake to Softbank and General Atlantic in 2020. Though the price was not disclosed, it predated much of Kavak’s value appreciation. The Series C, which was announced five months after the Nazca news surfaced, pegged Kavak at $1.15 billion – roughly a year later, it had swelled more than 7.5x.

Life in the fast lane

Around the time that Kavak closed its first round of funding, Loreanne García joined as its third co-founder. In many respects, Carlos García had followed in the footsteps of his elder sister. Loreanne had studied in Venezuela before receiving an MBA abroad, attending Stanford. She had spent five years at McKinsey, split between Latin American offices and a post in San Francisco. She had moved to Mexico first, relocating the year before García.

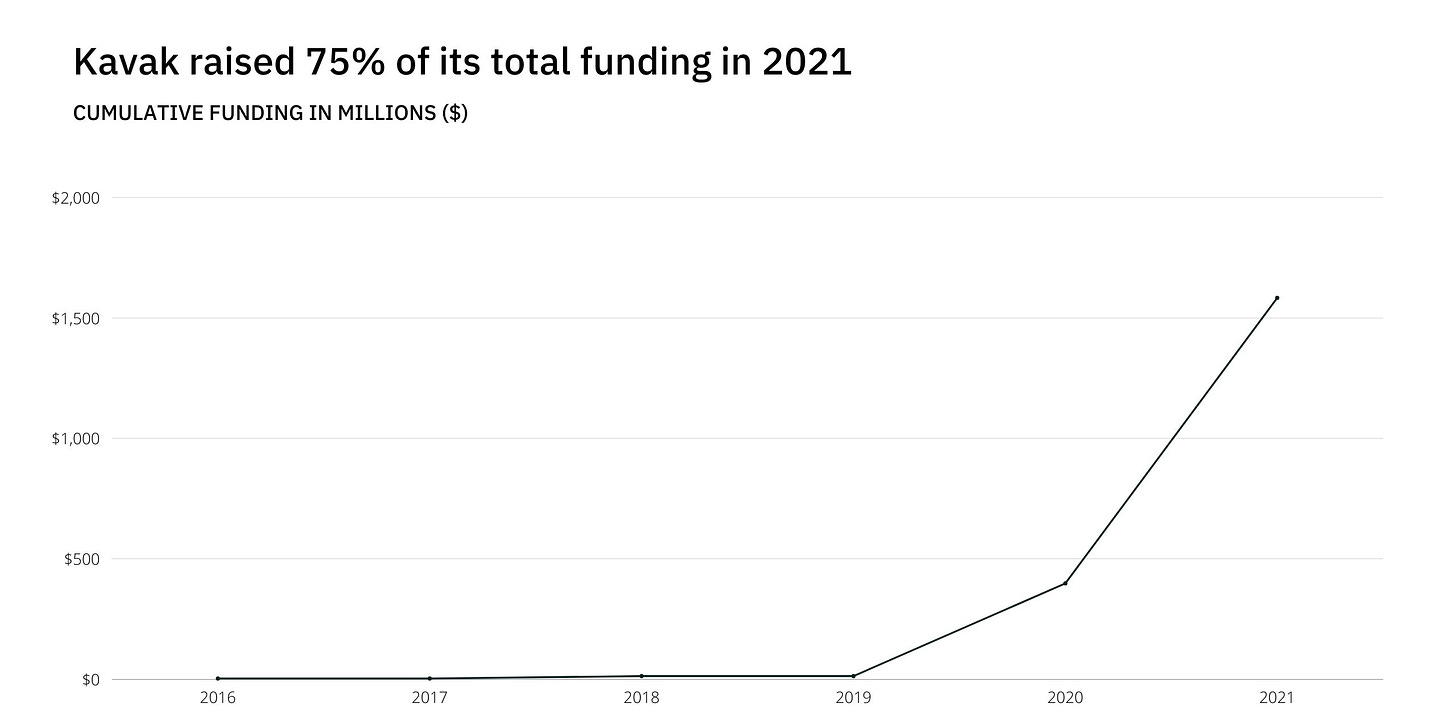

Though Kavak would later raise considerable funding, the company ran economically for much of its life. From mid-2016 to mid-2020, Kavak pulled in just $13.3 million in capital, adding a $10 million Series A led by Kaszek Ventures to its seed.

García believes that leanness produced Kavak’s subsequent strength. Running a used car marketplace is a capital-intensive business. You have to buy cars from customers to sell them to others. Realizing Kavak could burn through its funding if it were not an intelligent buyer, García devoted most of the early resources to advancing the pricing algorithm he had started tinkering with back in 2013. It would become one of Kavak’s most significant moats, driving efficient growth.

A second advantage arrived in 2020 with the launch of Kavak Capital. García had long known that a lack of automobile financing represented a significant problem for Latin American consumers. To address the problem, he launched an in-house fintech arm to provide car leasing. Kavak also partnered with financial institutions like HSBC, BBVA, Santander, and Credimovil to expand this offering.

Mega-funding arrived soon enough. The $385 million Series C mentioned earlier saw Kavak welcome Softbank, DST Global, and Greenoaks to the cap table. It also marked Kavak’s coronation as Mexico’s first-ever unicorn business. García quickly put the capital to work, expanding the number of “reconditioning” centers the company uses to bring the cars it purchases up to standard. He also undertook Kavak’s first piece of M&A, sealing a deal to absorb Argentine competitor, Checkars for $10 million. That move pushed Kavak into a new market.

Over the next twelve months, Kavak grew from a few hundred to 5,000 employees, boosted by a further $1.85 billion in capital, split across two rounds. An April Series D valued the business at $4 billion, and once again, García used the money to grow Kavak’s scope. Along with his commitment to invest $500 million in the Brazilian market, the CEO acquired another business: Turkish startup, Garaj Sepeti. Breaking the traditional regional playbook, Kavak set up shop beyond Latin America, leveraging Garaj Sepeti to break into Turkey. As we’ll discuss later, it was a surprisingly logical move.

Months after the Series D, Kavak raised again. A $700 million Series E led by General Catalyst valued the firm at $8.7 billion. While we’ll investigate the merits of that valuation later, the uptick reflected growing traction, with García reporting that Kavak’s revenue was doubling every three to five months.

Despite a dour market in 2022, García is set on continuing his global conquest. Last week, AIM Group noted that Kavak had “quietly” launched versions of its website aimed at consumers in Peru, Colombia, and Chile. Though Kavak’s proliferation undoubtedly owes much to its impressive team, it has been helped by the characteristics and quirks of the Latin American market.

Market: Perfectly engineered

In our piece on Nubank, we described how the Brazilian banking startup had capitalized on a market that seemed “perfectly broken.” Vulnerabilities could be mapped nearly perfectly to the insurgent strategy CEO David Vélez executed.

The same seems to be true of Kavak. It is a business perfectly engineered to the circumstances. Though there are meaningful differences between countries, we can distill the Latin American used car market into five critical traits:

The used car market is large and very fragmented.

Transactions are peer-to-peer, unstructured, and vulnerable to fraud.

Car ownership is highly concentrated in metropolitan areas.

Financing options are limited or effectively non-existent.

The economic importance of a car is pronounced.

Much of the information below relies on private research from a firm with expertise in the space.

Large and fragmented

While more new cars are sold in China each year, the United States is the largest purveyor of used vehicles. Roughly 43 million are sold in the States each year, far beyond China’s 14.9 million.

Though a regional rather than a national market, Latin America outstrips China with an estimated 21 million transactions. Brazil alone logs approximately 14 million transactions, making it the world’s third-largest market.

This size translates into a meaningful opportunity, with Brazil’s total addressable market estimated at $140 billion. Mexico is roughly 40% of Brazil’s size, with a market of $60 billion, while Argentina’s comes in at $15 billion. The Latin American market is growing at a compound annual growth rate of 4% per year.

The market is attractive for a newcomer like Kavak, thanks to the absence of a dominant incumbent. Such fragmentation is a relatively global phenomenon – CarMax is the leader in the US with only a 2% stake – but it is especially pronounced in Latam.

Luca Cacifi, the founder of Instacarro, a Brazilian player, noted that “95% of the [Brazilian] market is dominated by family-owned businesses and mom-and-pop shops.” No player has more than 1% of the country. In Mexico, the matter is even more conspicuous. Today, Kavak is the national leader with just 0.4%.

Unstructured transactions

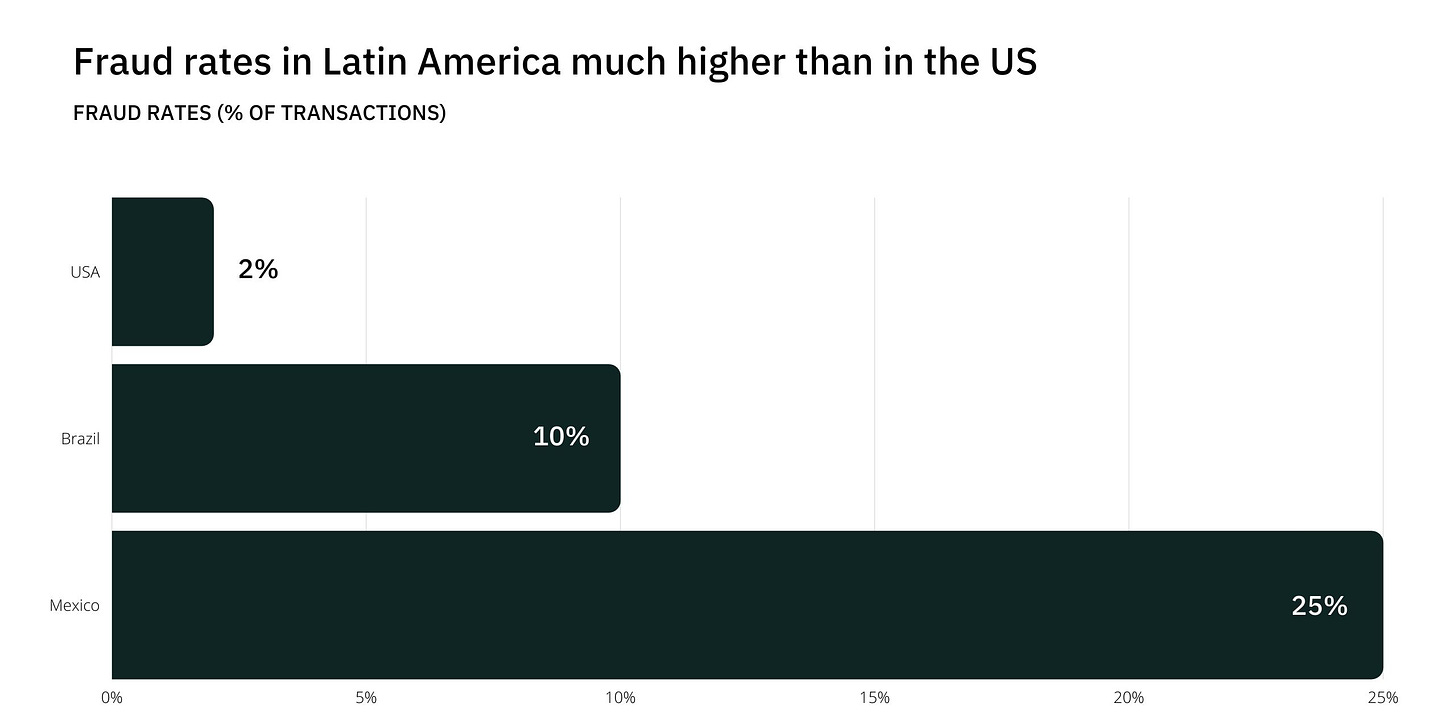

Perhaps because of this fractured state of play, many used car sales occur without an intermediary. Peer-to-peer (P2P) transactions comprise roughly 60% of the total in Brazil and Argentina and 80% in Mexico.

These interactions are especially fraught because of the high rates of fraud. While the rate of fraud in the United States is 2%, it is 5x that in Brazil and 12.5x in Mexico. Fully 25% of transactions in Mexico fall victim to fraud, whether that involves theft, unfair pricing, or misrepresenting the asset.

If you buy a used car in Latam, there’s a good chance of getting robbed, gouged, or stuck with a lemon.

Part of the reason this is so commonplace is that there’s an absence of standardizing entities. Kelley Blue Book acts as a used car pricing Bible in the United States, while Carfax gives a vehicle’s history. Both facilitate transparent and fair transactions, giving the buyer a benchmark and valuable accompanying information. While some pricing services exist in Brazil, they are sparse elsewhere on the continent. There is no Carfax equivalent.

Concentrated in cities

Though he may not have realized it at the time, when García relocated to Mexico City, he had chosen the perfect hub from which to launch a Latin American used car marketplace. Seventy percent of used car sales occur within the country’s top three cities, with the vast majority concentrated in the capital. In Argentina, 58% of transactions happen in the three largest metropolises, while Brazil’s big three see 50%. Again, this represents a major difference from the United States, which sees 20% of equivalent transactions.

While a US company would have to build an expansive web of offices and reconditioning centers to get within range of 50% of transactions, Kavak was able to do the same in Mexico with effectively a single metropolis. This dynamic has also aided expansion.

Minimal financing

America is anomalous regarding the rate of used car purchases that receive financing. Seventy percent benefit from such services, compared to just 27% in the United Kingdom. Brazil is closer to the latter with rates of 30%; Mexico sits at just 5%.

This dearth has a profound impact on car ownership rates. Despite being the third-largest used car market, Brazil ranks fifty-first by vehicles per capita with 366 per 1,000 people. Argentina and Mexico both sit further down the list. This combination of figures suggests that while plenty of buying and selling activity occurs in these countries, large portions of the population remain locked out of owning a car.

Economic importance

For low-income families, owning a car changes everything. In the United States, countless studies have shown that access to an automobile improves the likelihood of getting a job, keeping it, increasing earning power, and leaving governmental welfare programs. It also helps avoid delays in crucial medical care, increases school selection, and makes it easier for children to participate in extracurricular programs that may aid development.

A car may be especially important in Latin America. Most major metropolises have relatively weak public transportation systems, meaning there often isn’t a good alternative available. Another important consideration is that, for much of the population, buying a car may be the biggest purchase they make in their life. Brazil’s GDP per capita is $6,796, while Mexico’s is $8,329. The first car listed on Kavak’s Mexican site costs nearly $10,000; the Brazilian version shows one priced at more than $17,000. (This further emphasizes the need for financing.)

Hernán Kazah, the founder of Mercado Libre and venture firm Kaszek, likened the transaction to buying a house. “For many people the car is the main asset that they own,” he said. “And it really is an asset.”

Product: Consumers first

García has built an end to end product that revolutionizes the customer experience. In doing so, Kavak has created standards for the unstructured Latin American market, expanded access to vehicle financing, and put consumers first.

Selling

Carlos García has created the product he wishes he’d had when trying to sell his car back in Bogotá. Kavak provides a simple, easy way to offload your vehicle at a fair price.

To start, consumers enter their vehicle details into Kavak’s website. The company accepts cars from 2010 or later and only particular models. Once the information has been submitted, Kavak’s algorithm goes to work. In two minutes or less, it factors in the vehicle’s information, usage, market trends, and prices on similar sites to provide a preliminary market value.

After that, customers must book an inspection which can take place at home or a Kavak center. The company relies on a 240-point inspection process carried out by an individual who must go through three months of training and forty hours of job shadowing an existing inspector. At the end of this one to two-hour process, a final offer is given, which the customer has five days to consider.

Notably, Kavak provides a range of options for the seller. Customers can receive immediate payment, credit towards a new car, or payment on consignment. Sellers with existing financing arrangements can also sell their car, providing they’ve paid down more than 50%.

From an operational perspective, Kavak’s goal is to hold on to the newly acquired car for as little time as possible, given its impact on cash flow. According to Hernán Kazah, Kavak’s process may become sufficiently fine-tuned to create a positive cash flow cycle: selling a car first and then dipping into the market to purchase it.

Buying

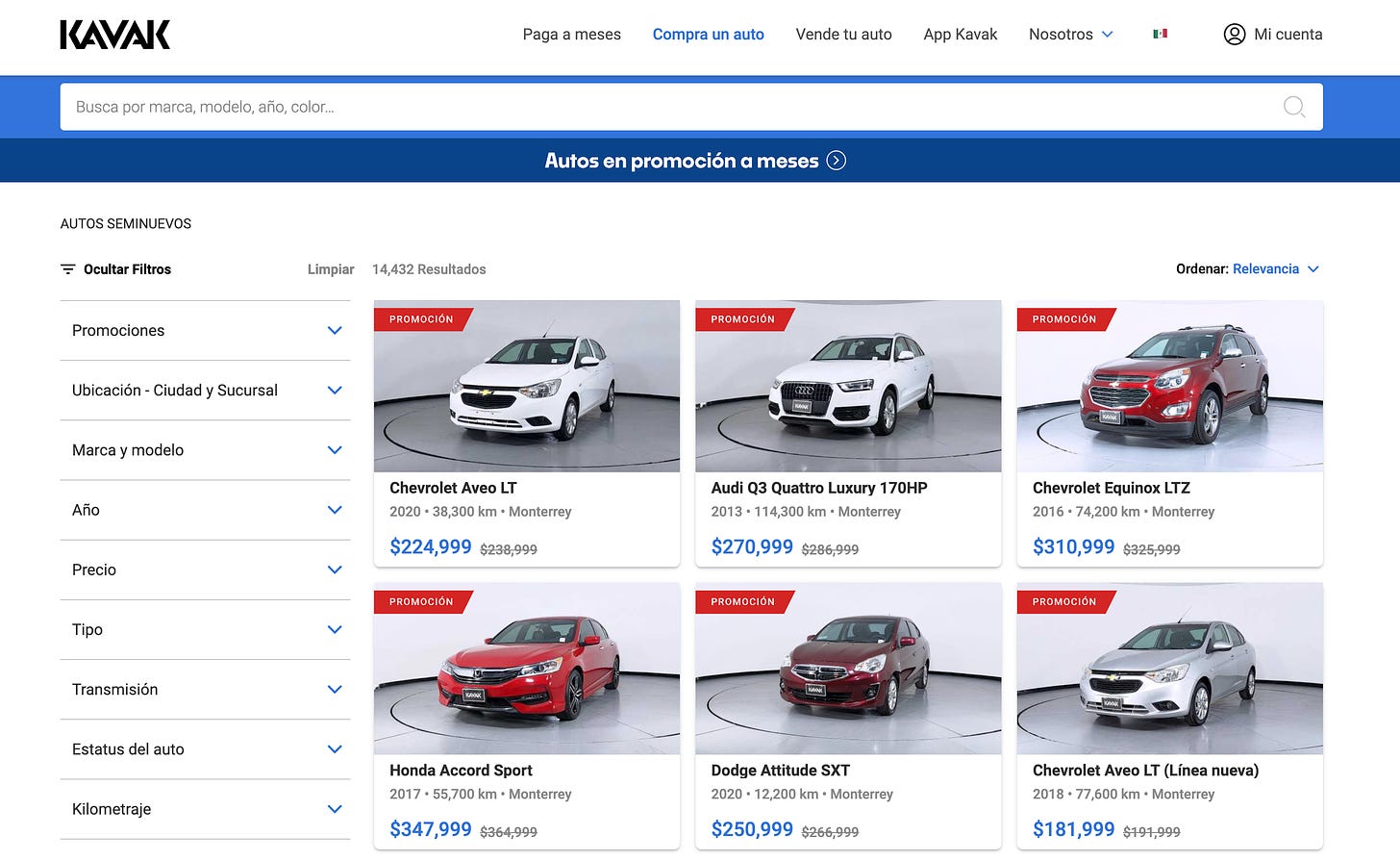

Kavak looks to make the buying process equally smooth, even delivering purchased vehicles to customers’ homes.

The company’s website and app offer a range of vehicles, from SUVs to convertibles to sedans. Each listing includes detailed information on the car in question. Unlike the stereotypical car salesman that seeks to gloss over any imperfections, Kavak explicitly calls them out, providing photographic evidence.

These are part of Kavak’s “reconditioning” process that sees the business get vehicles into sellable shape. Kavak ensures brakes and tires have at least half of their life left and that the car is in reasonable condition. In total, reconditioning can cost Kavak around $1,000. The company currently has more than forty reconditioning centers.

All Kavak purchases can be returned in seven days or until a customer has logged 300 kilometers. The car is insured for three months by default though buyers can extend this to fifteen months by purchasing Kavak Total, the company’s insurance product. Repairs and maintenance can be booked through Kavak’s app.

Financing

To make car ownership more accessible, Kavak provides robust financing through its subsidiary, Kavak Capital. Consumers receive multiple leasing options in less than two minutes with interest rates between 14% and 20%. While that may sound steep by US standards, it is considerably better than the sparse local options, which may reach up to 60%. Kavak’s financing advantage can be traced back to the algorithm mentioned earlier. One investor noted, “Kavak understands these cars better than everyone.”

It is working. While Kavak partners with financial institutions to extend its selection, García reported that more than half of financing is handled in-house. In sum, Capital plays a critical role in the business model. Not only does it expand the total addressable market, giving new buyers access to car ownership, but it also increases conversion. Moreover, since selling used cars has thin margins, Capital adds a higher-margin revenue stream. Along with insurance and repairs, financing helps increase Kavak’s average revenue per user (ARPU) and creates a long-lasting consumer relationship.

Leadership: Benevolent dictators

Ask anyone what makes Kavak special, and it doesn’t take long for the question of talent to emerge. Like few other businesses, investors speak about Kavak’s team in awed tones. While much of that begins with Carlos García, it extends to his co-founders and the broader leadership. One investor remarked that much of the talent at Kavak “could be entrepreneurs in their own right.”

The secret behind attracting exceptional operators lies in the brilliance of García and the culture that has been created.

A generational founder

Perhaps only Marcos Galperin of Mercado Libre and David Vélez of Nubank have been described to me with as much reverence as García. Those who invested in Kavak characterize him as a generational founder with rare gifts.

Hernán Kazah told the story of how García first won him over at the time of Kavak’s Series A. As he remembers it, Kazah was initially “hesitant to invest” given Kavak’s capital-intensive model. But when he met García, his concerns quickly evaporated.

“He convinced me he was an extraordinary entrepreneur, in capital letters,” Kazah said. “This guy is clearly very, very unique.”

One of García's most attractive traits is his ability to balance ferocious ambition with tactical awareness. “On the one hand, you could see he was willing to tear down the wall in front of him,” Kazah said. “But at the same time, he was very thoughtful about what steps to take next. He was very thoughtful about sustainability.” In that respect, García seems to have learned directly from Linio’s profligacy; indeed, Kazah described what García has built as the “anti-Rocket model.” “He’s not just about growth,” the investor added.

Beyond his drive, García is reportedly an excellent motivator. Kazah described him as a “cheerleader” capable of rallying a team around a common goal. That seems to be due to his ability to connect the used car market to a broader mission. In interviews, García often notes the importance of automobiles in opening pathways to the middle class, giving Kavak’s work additional gravitas.

Loreanne García and Roger Laughlin were also described very positively. Loreanne is “mostly focused on people,” according to one source, meaning her work centers around talent, culture, and human resources. Laughlin has been made CEO of Kavak’s Brazil division, a move that a source pointed to as an indication of the company’s commitment to the geography – while other startups appoint a GM to manage a new market, Kavak sends a co-founder. It doesn’t hurt that Laughlin previously worked in the country at Groupon.

Participatory dictatorship

Kavak has strength beyond its leadership. García has described the company’s culture as one of “participatory dictatorship.” On the Cracks podcast, García gave an analogy to explain what that means.

Specifically, he referred to the Fast and Furious movies. (Presumably, the later heist-oriented films, though I am far from an expert.) As he explained it, the squad in the movie remains in constant discussion, but each member is behind the wheel of their own car. At Kavak, it’s similar: each person has a mission they are given decision-making control over. But this power exists in relation to a larger group that should be in constant communication. The result is a culture of extreme ownership allied with collaboration.

Don't miss our next briefing. Our work is designed to help you understand the most important trends shaping the future, and to capitalize on change. Join 58,000 others today.

Valuation: Overheated

Kavak seems to be an undeniably good business. Though García has not shared numbers, the firm’s financing history and market expansion suggest as much. The question becomes: is it worth $8.7 billion?

Given how drastically public market sentiment has changed with respect to used car marketplaces, it seems unlikely Kavak would receive the same valuation today. Investors’ re-examination of public comps like Carvana and Vroom raises questions about the fundamental limitations of Kavak’s business.

Public players hit the skids

Kavak announced its new $8.7 billion valuation on September 22, 2021.

On that day, Carvana’s market cap stood at roughly $57 billion, Vroom’s at $3.2 billion, Cazoo’s $7 billion, and CarMax’s at $22.7 billion. Exactly eight months later, all four are significantly reduced. CarMax has fared best, falling 34% to a $14.97 billion market cap. Carvana has collapsed nearly 90% to just $5.96 billion, while Vroom has been hit even harder, collapsing to just $198.5 million, a roughly 94% decline. Cazoo, a European player, fell 84%, even though its Q1 earnings showed 159% annual revenue growth.

Though they may have a longer time horizon, every growth stage venture capitalist looks to the public market for comparison. Subsequently, Kavak’s later rounds will have been progressively influenced by the fortunes of public players. Valuing Kavak at nearly $9 billion has an explicit logic when Carvana is within touching distance of $60 billion; it seems conceivable that Series E investors might have reasonably expected a 2-3x markup within two years, on this basis.

The change in the macro environment means that Kavak would not command the same valuation today. This is not a criticism – many great companies raised large sums of capital at high valuations over the past few years and were often right to do so. Kavak also does not seem to be part of the class of companies whose growth depended only on burning capital. According to investors, though 2022 has necessitated a more frugal approach for every business, Kavak has continued to climb. “The growth is there,” one source noted, “We’re all very happy with the performance.” Clearly, the company believes now is not the time to let up – hundreds of open positions are advertised on Kavak’s website.

From what I’ve heard about García, managing Kavak’s purse strings sensibly seems firmly within his skillset. While navigating the business to an IPO that gives Series E investors a profitable outcome will require the cooperation of the public markets, there is no sense that Kavak is a distressed asset or running against the clock. One investor remarked that given the maturity of its Mexico presence, Kavak could accelerate profitability in that geography if it wanted. Having that option is a boon, though it may not answer fundamental questions about the business.

Fundamental questions

The question of whether Kavak is overvalued is a transient one. Maybe it is today, but won’t be in six months. The more fundamental question may be: is Kavak a tech company?

From one vantage, it seems to be. Technology is woven into the company's operations. Not only is it the way it provides its services and communicates with customers, but it is also how Kavak sets prices and handles financing. García describes Kavak’s technological infrastructure as an iceberg – customers see just 20% of its mass.

Equally, Kavak is a physical business with real-world operations. It buys large objects, picks them up, renovates them through manual and mechanical labor, and delivers them. Technology can govern and assist that process, but it cannot occur anywhere but in the tangible, corporeal realm. The result is a business with significant capital requirements and limited scalability. Kavak needs access to funding to grow the supply on its marketplace and provide financing. Launching a new market takes more than just a new website. Reconditioning centers, parking lots, and showrooms are all necessary. This makes Kavak very different than a marketplace like Airbnb, for example, which does not need to take possession of the underlying assets.

Because of this dynamic, companies like Carvana and Cazoo have maintained relatively thin margins. Carvana’s most recent gross margins were roughly 8.52%; its EBITDA margins have slumped to -11.6%. In 2021, Cazoo reported gross margins of 3.3% and adjusted EBITDA margins of -27%. Even mature, albeit even more physically-intensive businesses like CarMax, see similar figures with a gross margin of 9.25%. The company’s EBITDA margin is much improved at 5.53%, going some way to explaining why its fate has diverged so starkly from Carvana’s.

Ultimately, these are a long way from software margins. That’s not to say that Kavak cannot build a large, impressive business. But it may mean there is a stronger gravitational pull on the company as it scales. Today, the largest used car marketplace globally, Copart, has a market cap of just $26.6 billion, though we are undoubtedly judging the space at a low point. Nevertheless, the dynamics of Kavak’s model may impact how large it can get.

Future: Brazil and beyond

García gives the impression of a relentless founder on a mission to build one of the most valuable companies in the world. To make that happen, he is building an aggressively global business that may soon have a meaningful presence in Asia and the Middle East.

Geographical expansion

Given Brazil’s prominence in the Latin American used car market, it’s unsurprising that Kavak has decided to enter the country. It represents the biggest regional opportunity by some margin and, as such, the most attractive prize for other tech-savvy upstarts to target. Creditas, a consumer loan startup, acquired used car platform Volanty last year to fortify its Creditas Auto division. Luca Cacifi’s Instacarro is another venture-backed player, though, as he noted, the company takes a different tact to Kavak, selling to dealers instead of consumers.

The size of Kavak’s investment shows that they are playing to win in Brazil. Five hundred million dollars represents 45% of their last two rounds of financing, illustrating that it is the company’s top priority. Roger Laughlin’s relocation to the country is further evidence; one source suggested that they would not be surprised if García made the same move.

So far, Kavak’s foray seems to have been successful. The same source remarked that numbers in the country had been positive to date, adding, “What they’ve done in Brazil is pretty incredible.” Expansion into Rio de Janeiro is another show of confidence.

If Kavak’s Brazilian adventure seemed inevitable, its foray into Turkey is more unusual. Latin American startups tend to follow a familiar pattern: those that start in Mexico soon move to Brazil; those that begin in Brazil invariably make their way north. (Those that start anywhere else quickly move to grab one of those markets.) Once those two markets are locked down, the company moves to pick off smaller regional markets like Colombia, Argentina, Chile, Peru, and Ecuador.

García's decision to take on the Turkish market before adding many Latin American countries is a testament to his audacity. Though he seems to want to win his local region, he has bigger designs. When I asked one source why Kavak had chosen the country, they outlined a rational process García had gone through. Rather than picking the easiest market to tack on, García decided to attack the biggest one without an established winner. With 7.5 million used car sales per year, Turkey is the sixth largest market, outstripping Mexico, France, Russia, Indonesia, India, and Spain. (As it happens, Turkey was also a linguistically strong choice: “Titrek Kavak” is a type of aspen considered lucky in the country.) So far, Kavak – or Carvak as it is known locally – has three shopping locations in Istanbul.

Looking at job openings gives us a good idea of where Kavak is headed next. Among roles in Brazil, Argentina, and Turkey are fourteen in the Middle East, predominantly in Dubai. Given that Kavak categorizes these openings under “GCC” (The Gulf Cooperation Council), we should expect ambitions to stretch across all six countries in that group: the United Arab Emirates, Saudi Arabia, Qatar, Oman, Kuwait, and Bahrain. From there, Kavak could extend to Egypt in the east or move up into Iran. The latter has one of the highest car ownership rates in the world. In the past, Kavak has used M&A to access new markets, picking up Checkars in Argentina and Garaj Sepeti in Turkey. We should expect similar maneuvers as it expands beyond its current ken.

India would represent a bold but complicated move. The country’s used car market is growing at a CAGR of 11% per year and is expected to crest 8.3 million transactions by 2026, making it one of the largest markets in the world. Unlike some of the other geographies Kavak has targeted, well-funded competitors exist. CARS24, Droom, CarDekho, and Spinny have all raised in the hundreds of millions and gained meaningful traction. While the fragmentation in the market means there is room for multiple winners, the presence of modern alternatives reduces Kavak’s relative value proposition. The size of these competitors makes M&A activity difficult, too.

“Super app” ambitions

Kavak doesn’t just want to grow geographically. Listen to García's rhetoric, and it’s clear he sees an opportunity to expand the company’s feature set. As part of the last funding round, the CEO outlined his ambition for Kavak to be a “super app experience” that bundles multiple services into a single package. To a certain extent, Kavak has already achieved that goal, providing an extremely fully-featured product for buying, selling, financing, servicing, and insuring one’s automobile.

The effect of bundling these features is profound. First, layering services increases Kavak’s average revenue per user (ARPU) and lifetime value (LTV). It resembles Nubank in this respect; the challenger bank has successfully used credit cards as a wedge to win other financial relationships. The company’s recent quarterly presentation showed that Nubank is increasing the number of products active customers use and that by doing so, they are growing revenue per customer. Though the average revenue per active customer (ARPAC) is $6.70, Nubank notes that “mature cohorts” hit $19 per month.

Kavak is doing something similar. As it rolls out its full suite of services across markets – adding insurance and financing to Turkey, Colombia, Saudi Arabia, and beyond – it stands to see sharp revenue growth even without adding new customers.

Second, by changing the customer relationship from one-off to continuous, Kavak increases the likelihood of securing the next big purchase. When it comes time to upgrade from a hatchback to a sedan, Kavak has all the necessary information: details on the car to be sold, active insurance policies, and financing history.

So, what’s missing? The secret may be in not complicating it too much. Kavak already acts like a one-stop automotive shop in mature markets, even making it easy to pay fines. The best thing the company can do is achieve feature parity across its current scope and drive multi-product adoption.

Car rentals may represent one missing piece. In addition to opening up Kavak’s inventory – which may sometimes sit unused – the company could facilitate a managed, peer-to-peer model, giving customers another way to benefit financially from ownership. Succeeding on this front would be complex, relying on Kavak’s skill in reducing fraud and abstracting away consumer pain points, but it might be worth the pain. The company could improve utilization rates, increase ARPU, and build actual network effects.

“We are like conquerors. As long as we have breath to give, we are going to be searching, building, and growing.”

This is how Carlos García described Kavak’s culture; a business engaged in an infinite game.

In Fordlandia, we see the hazards of unchecked hubris and wild ambition. Though follows Ford in seeking to disrupt the world of mobility and placing a concentrated bet on success in Brazil, that is where the similarities begin and end. Kavak City is not some far-flung goose chase but a statement of intent in keeping with the core business. We should expect it to last much longer than Ford’s experiment.

That is not to say will not face failures or setbacks. It remains to be seen whether Kavak can grow into its heady valuation or if it can achieve similar success in Turkey and the Middle East as it has in Mexico. Despite its investment in technology, it remains a capital-intensive business that scales only as fast as it grows a commensurate physical footprint.

What we can say is that Kavak will not stand still. Like the product it sells, it needs to move, to push forward, to conquer. That drive should take it far.

The Generalist’s work is provided for informational purposes only and should not be construed as legal, business, investment, or tax advice. You should always do your own research and consult advisors on these subjects. Our work may feature entities in which Generalist Capital, LLC or the author has invested.