The tumble of voices falls silent.

The lights come up.

Bulbs illume a long, gleaming catwalk as a bubbly song fills the air. It takes a moment to place it despite the familiarity of the melody. A cover of Don McLean’s “American Pie,” stripped of its sorrow, sugared into an electronic confection.

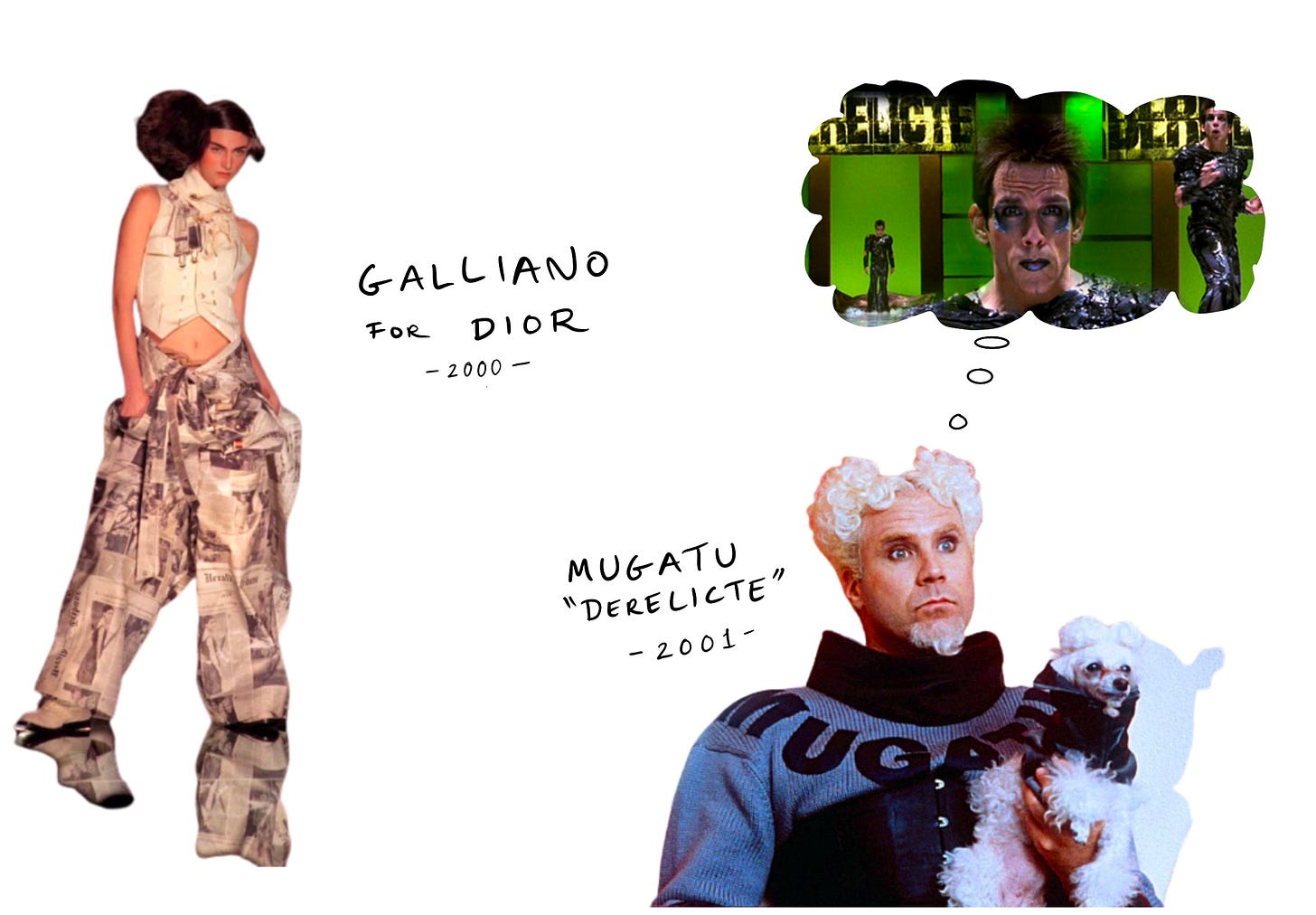

A lank, miserable figure saunters down the stage, hands in her pocket. Hair balled and puffed to one side — a second head — she wears a white vest, a delicate scarf, a glistening, belt-like necklace.

And newspaper.

Her trousers, baggy, but fastened with a studiously casual cordon, are made entirely of paper, broadsheets crafted for a narrow body.

Taken together the vision is striking: a peek into a glamorous, imagined demi-monde; comely agony.

That was precisely what John Galliano had wanted. As he told a gobsmacked press after the 2000 show, he’d been inspired by his encounters with Paris’s homeless, passing them as he ran along the Seine.

Some of these people are like impresarios, their coats worn over their shoulders and their hats worn at a certain angle. It's fantastic.

Fantastic, perhaps, but witless, too. Can genius be moronic? Anyone that heard the plan for a luxury brand to take inspiration from the homeless should have recognized the noisome condescension of the extremely wealthy aping, romanticizing the poor. Miniature bottles of liquor jangled alongside spoons and at models' waists; cigarette burns mottled fabric.

(Zoolander would brilliantly lampoon the absurdity of Galliano’s collection just a year later with the titular character modeling “Derelicte,” a line from the film’s villain Mugatu, “inspired by the very homeless, the vagrants, the crack whores that make this wonderful city so unique.”)

Whatever controversy it stoked, it didn’t matter; Galliano’s collection was a smash. As the designer gloated, “'One can't go into a restaurant without hearing fantastic young ladies talking about the fraying of tulle of the Christian Dior show.” Within a year, Dior had turned his fragile newsprint pantaloons into a commercially successful fabric collection.

It could only have happened at the conglomerate for which Galliano worked: LVMH. Forged from a trio of luxury brands in the late-1980s, LVMH has matured into the undisputed leader of luxury under the stewardship of CEO Bernard Arnault. It has done so animated by a uniquely artist-led philosophy, respect for heritage craftsmanship, and a knack for managing generational change. With creativity (and the creator economy) playing a more prominent role in the tech sector, LVMH’s wisdom feels particularly applicable.

The company will need to draw on all of those talents over the next ten years. As the singular Arnault traverses his eighth decade, couture is captivated by new fashions, and competitors jockey to take a pop at the champ, LVMH’s future looks uncertain for the first time in thirty years.

In today’s briefing, we’ll explore:

LVMH’s contentious formation

The company’s decentralized “Maison” structure

The extraordinary philosophy guiding the business

Threats to another generation of excellence

The Rise of Arnault

The first thing to know about Bernard Arnault is this: you must never invite him in. Like the fox that charms his way into the henhouse or the business world’s Babadook, the Frenchman has mastered the art of gaining access, then pressing his advantage. As the man himself once said, “in business, the secret is to seize opportunities.”

The world’s fourth-richest man has done so better than just about anyone else. Over the past half a century, Arnault has shown the ruthlessness, cunning, and vision to turn moments of uncertainty into defining triumphs.

It is a story almost Shakespearean in its intrigue.

Family business

Born in the Northern city of Roubaix in 1949, Bernard Arnault first dreamt of becoming a concert pianist. He showed promise in his youth but recognized in adolescence that he lacked the necessary skill to become a professional artist.

Instead, he prepared to enter the family business. His mother, a cultured woman with a love for Christian Dior (what an omen), was the heiress to a minor construction and civil engineering fiefdom, managed by her husband. It was only fitting then that Bernard matriculated to the École Polytechnique, the country’s finest engineering school, before taking a role at the company in 1971.

It did not take long for the younger Arnault to impose his steely vision on his inheritance. It didn’t hurt that his father trusted his son’s instincts from the beginning, putting him in charge of 100 employees. Empowered and driven, Bernard persuaded his father to sell off its industrial construction division to focus on real estate before convincing him the revamped organization required a new name. The clunky Ferret-Savinel became the sleeker Ferinel.

With those adjustments made, Arnault set about growing a real estate empire, first in France, then when a socialist government curbed domestic entrepreneurship, in the US.

America had an enduring impact on the young executive. The brashness and boldness of the business culture were so different from his home country’s understated gentility, he noticed. It was sharper, more ambitious.

He liked it. That’s what French enterprise needed, wasn’t it? A shake-up? Someone with vision and the fearlessness to bring it to fruition? It needed someone like him, Arnault must have thought from his home in New Rochelle.

It was time to return to Paris.

Groupe Boussac

For all his success expanding Ferinel, nothing in Arnault’s past suggested he was capable of his next move.

Maison Dior had fallen on hard times. Founded in 1947, the couturier’s parent company slumped into the 1980s. That was less to do with the performance of Dior than the other businesses weighing down “Groupe Boussac,” including a flagging textile business and disposable diaper brand.

After declaring bankruptcy in 1984, the French government stepped in to find Boussac a buyer.

Arnault couldn’t believe it. One of the country’s most beloved and prestigious brands was for sale and at a discount! But even in its distressed state, buying Boussac looked beyond Arnault’s means. After all, the French government wanted someone who could commit to investing in the business. Though Ferinel did well, the $15 million in annual revenue it brought in was still a far cry from the capital needed.

But Arnault was not to be deterred; he would get the money, one way or another.

His salvation came in the form of Antoine Bernheim, an investment banker at Lazard Frères. Though a quarter of a century older than Arnault, Bernheim shared the younger man’s chutzpah. Born to Jewish Parisians, Bernheim had been hardened by life with both of his parents murdered by Nazis during World War II. He had only survived by taking refuge in the Italian Alps.

That brutal upbringing had forged an unusually defiant capitalist, willing to take risks. And when Arnault pitched him on financing his purchase of Boussac, he found one worth taking.

In 1984, Arnault acquired Boussac for a token franc. The actual cost of the deal was $80 million, with Lazard financing over 80% of it. The rest came from the coffers of Ferinel.

He wasted little time in conforming Boussac to his vision. Despite promising to keep jobs and maintain the group’s structure, Arnault slashed aggressively, selling off unprofitable divisions and re-centering the business around Dior. With that streamlining went 9,000 jobs. The name changed, too, this time to Financiere Agache.

Whatever one thinks of Arnault’s gutting of Boussac, financially, it proved the right call. Over the following few years, Agache stabilized, then flourished. By 1987, the company earned $1.9 billion in revenue a year and netted $112 million.

The turnaround had worked, but Arnault was just getting started. He told reporters: he was going to build the biggest luxury company in the world, just give him ten years.

Rushing to the altar

If Arnault was at the beginning of his career, Henry Racamier was reaching the end. Considered one of France’s most impressive executives, the patrician head of Louis Vuitton had only taken over his wife’s family business in 1977, after a successful stint helming steel firm, Stinox.

Racamier was 65 by that point but far from past his prime. Over the ensuing decade, he took an esteemed if sleepy firm from two stores and $14 million in revenue to 135 and close to $1 billion.

Starting almost a decade before Racamier, Alain Chevalier had overseen a similarly successful (if not quite as miraculous) uptick at champagne manufacturer Moet. If Racamier was imposing and aristocratic, a long distinguished nose balancing a pair of thick, square spectacles, Chevalier attracted with softer charms. Chevalier offered an easy-going charisma that belied his shrewdness; in 1969, he demonstrated both in convincing Moet’s patriarch to hire him as CEO.

Chevalier made his defining move early on, shepherding through a merger with cognac provider Hennessey and expanding distribution to the Asian market. The new entity reached the late 1980s with $1 billion in revenue, more than a 300% improvement.

Chevalier’s first merger was driven by vision; his second was motivated by fear.

With the founding families controlling only 22% of Moet Hennessey, the company was susceptible to a takeover at a time when leveraged buyouts bewitched the financial world. In early 1987, noticing unusual trading activity, Chevalier set to secure the business. Over dinner at Maxim’s, a Parisian institution that had once hosted a scandalously barefoot Brigette Bardot, the three families — Louis Vuitton, Moet, and Hennessey — and their entourage discussed the merits of an alliance.

It didn’t take long to strike an agreement with the firms announcing the merger by the summer of the same year. “LVMH Moët Hennessy Louis Vuitton” or LVMH was born. As Chevalier described it, “It was like one of those love affairs that lead quickly to the altar.”

Like so many fleet-footed romances, conjugal bliss gave way to quotidian dread. Used to operating autonomously, Racamier chafed in the role as number two, agreed upon because of Moët Hennessy’s slightly larger size. He only grew more suspicious when Chevalier suggested selling 3.5% of the company to Guinness, led by old chum Anthony Tennant. What was LVMH: a luxury business or a liquor brand?

Chevalier reasoned that such a move made sense: not only was Guinness already a distribution partner, but bringing them aboard would further protect LVMH entity against the lurking Grand Metropolitan, the British conglomerate that owned Bailey’s.

No, Racamier thought. If LVMH were going to sell shares, it would be to someone of his choosing.

The Young Wolf and the Old Lion

And this is where we have to say again: you must never let Arnault in. No matter how sweetly he speaks, no matter how transfixing his ice-blue eyes, do not be fooled. Perhaps like Perseus with Medusa, he must be looked at only indirectly.

Whatever Arnault-bane exists, Racamier did not have it. In Arnault, the older man saw a protege, an heir-in-waiting. If someone had to buy a piece of LVMH, shouldn’t it be the luxury industry’s wunderkind?

He made Arnault a proposition: buy 25% of LVMH and join him at the table.

For Arnault, it was a chance to put his plans for world domination on hyperspeed and jockey for the missing piece of Agache; years earlier, Dior’s clothing and perfume divisions had been split, with the latter ending up in the hands of Louis Vuitton. Arnault wanted it back.

But when Arnault brought the deal to Bernheim, the banker was uncommonly circumspect. Owning a piece of LVMH was a remarkable opportunity, he agreed. But did Arnault really want to go against Chevalier and Guinness? Their money could crush him if they wanted to. Yes, he should enter the battle, Bernheim argued, but on the other side.

Oh, Racamier. In a string of backroom meetings, the Vuitton chief was recast, transforming from avuncular ally to enemy number one. In July of 1988, Arnault stunned the business world by teaming up with Guinness to buy a 24% stake in LVMH, worth $1.5 billion.

Racamier was incandescent, setting up a battle the French press dubbed the “Young Wolf Versus the Old Lion.” But the lion was not yet finished. To combat Chevalier and Arnault’s stranglehold, he set about galvanizing the Vuitton family to begin a share-buying spree. If they could edge ownership of the conglomerate up to 33%, they’d have a blocking minority, giving them the power to spoil management’s plans.

Arnault got there first. With another $600 million injection, he took his joint stake with Guinness up to 37.5%.

It was at this point, one imagines, that Chevalier began to question the wisdom of his alliance. Suddenly, this sharp-elbowed homme du nord had more than ⅓ of the business?

That figure didn’t last long. To prevent further fallout, Racamier and Chevalier tried to broker a detente: Louis Vuitton and Moet Hennessey would operate separately, and Arnault would take control of Dior’s perfume business? Win/win/win, right?

Years later, Arnault spat, ''Some people say I'm a wolf. That's not at all true. Wolves break up companies into pieces. It was Racamier who wanted to cut the company into pieces. I was the only one who did not want to dismantle it.''

Arnault countered, once again, with his checkbook: another $500 million took his stake to 43.5%.

Chevalier resigned, Guinness’s Anthony Tennant was exhausted, Racamier raged; all were powerless. War had distracted the company. It was time for a new beginning.

In January of 1989, Bernard Arnault was declared premier of the biggest luxury company in the world. He had achieved his goal in half the time.

Arnault twisted the knife just months later while demonstrating the personality that has defined his era, “'Chevalier was an excellent manager, but there is one big difference between us. He was not a shareholder of importance in the business he was in, but I make sure I am the controlling shareholder of the businesses I am in.''

King of Luxury

In the years since the War of the Three Giants, Bernard Arnault oversaw a period of remarkable growth. Much of that was achieved via acquisition, with key purchases including:

1988: Givenchy

1993: Berluti, Kenzo

1994: Guerlain

1996: Celine, Loewe

1997: Marc Jacobs, Sephora

1999: Tag Heuer, Thomas Pink

2000: Pucci, Rossimoda

2001: Fendi, DKNY, La Samaritaine

2010: Moynat

2011: Bulgari

2013: Loro Piana, Nicholas Kirkwood

2016: Rimowa

Though LVMH has amassed a dizzying collection of jewels, Arnault was not always successful. Some acquisitions have since been shed and attempts to snipe Gucci and Hermes ended in (lucrative) failure. But to dwell on such episodes would be to nitpick one of the most virtuosic executive performances of the past fifty years.

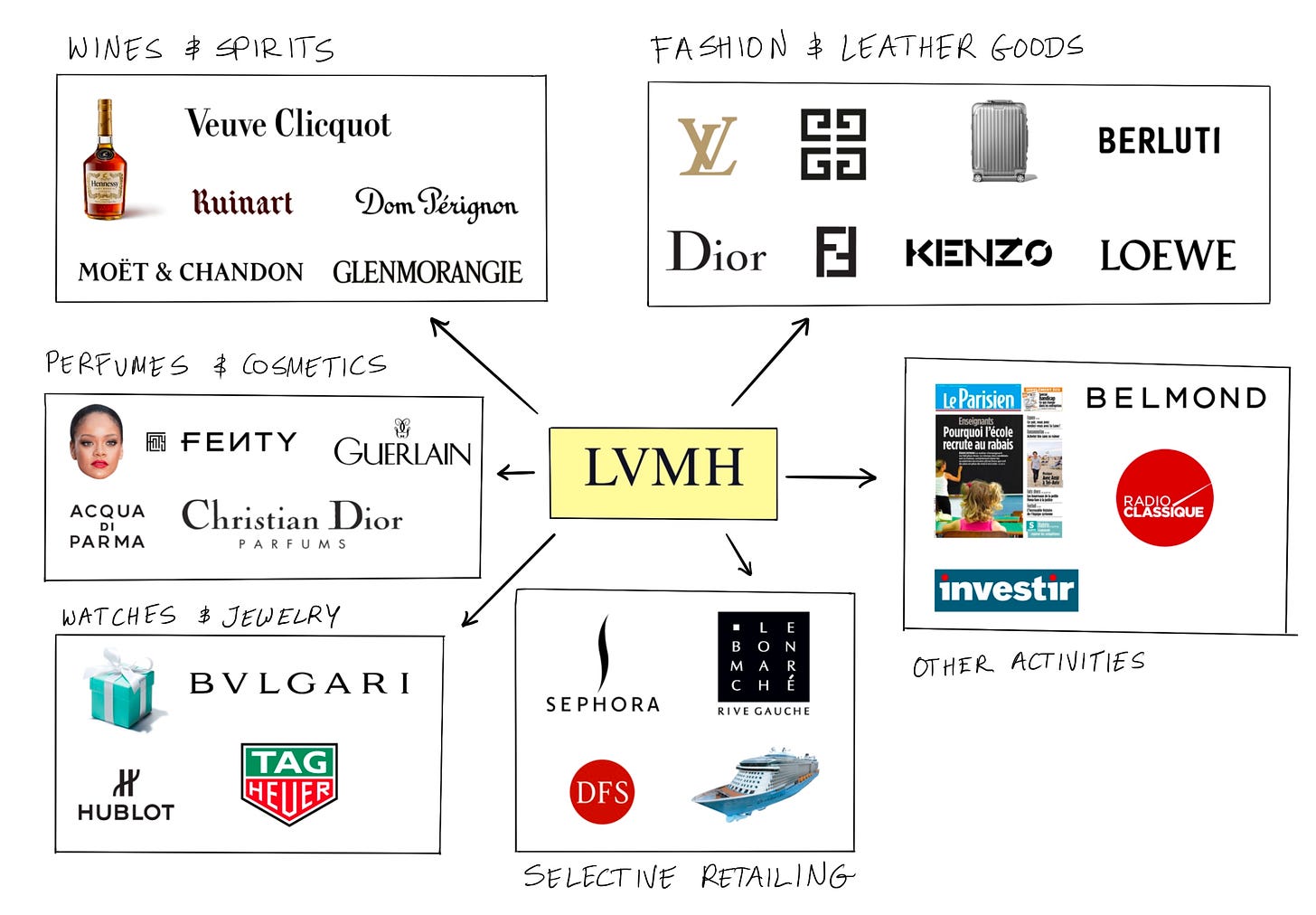

Today, LVMH includes 75 distinct companies (or “Houses” as the company prefers), employs more than 150,000 people, and brings in $54 billion in revenue per year. It boasts a market cap of $376 billion, greater than Netflix, Bank of America, Nestle, Intel, and Disney. It is a good day away from passing Walmart.

In the act of that value creation, Arnault fundamentally altered the luxury industry playbook. As the man himself noted, competitors like Richemont and Kering have subsequently followed suit:

I remember people telling me, it does not make sense to put together so many brands. And it was a success, it was a recognised success, and for the last 10 years now, every competitor is trying to imitate. I think they are not successful, but they try.

The final rejoinder is classic Arnault, unable to stop himself from landing a jab. In the man from Roubaix, LVMH found both the CEO it needed and the one it deserved — refined enough to spend his afternoon in front of a grand piano, practicing his Liszt, and vicious enough to drive performance. (One luxury commentator describes Arnault as “very hard, very violent.”) He and his conglomerate are delicate beasts, civil savages.

The Ontology of Opulence

Everything LVMH does is in service of a single aim: creating “star brands.”

What is a “star brand?”

According to Arnault:

I would say that there are four characteristics required. A star brand is timeless, modern, fast growing, and highly profitable…

In my opinion, there are fewer than ten star brands in the luxury world [as of 2001]. It is very hard to balance all four characteristics at once—after all, fast growth is often at odds with high profitability—but that is what makes them stars. If you have a star brand, then basically you can be sure you have mastered a paradox.

Louis Vuitton is, undoubtedly, a star brand. So too, Christian Dior.

To produce these stars, LVMH exercises a concerted process. While Arnault would be the first to admit that there’s an element of randomness involved — he is suspicious of “straightforward rationality” — there is nevertheless a distinct ontology that governs the conglomerate’s operations. That philosophy is marked by a preference for buying heritage, decentralized artistic governance, obsessive vertical integration, and a proactive approach to managing generational change.

Buying heritage

“Patience is a conquering virtue,” Geoffrey Chaucer once wrote. Arnault would not agree with those words from the author of The Canterbury Tales, though he has shown an affection for companies steeped in tradition.

As mentioned above, LVMH has primarily grown through acquisitions. While that might not have been de rigueur in the luxury industry before Arnault’s arrival, it’s an approach leveraged by many conglomerates. But what marks out LVMH’s strategy is the type of business it buys. Since taking over, Arnault has relentlessly pursued companies with unique historicity.

In 1365, the same year that Chaucer married the courtier Phillipa Roet (“What is better than wisdom? Woman. And what is better than a good woman? Nothing.”), Clos des Lambrays vineyard opened its doors. In 2014, nearly six hundred and fifty years later, it was acquired by LVMH.

It’s fair to assume that the Burgundy producer has done little to move LVMH’s bottom-line: just 11% of revenue comes from wines and spirits, with most coming through champagne and cognac sales.

Why would the company make such a move?

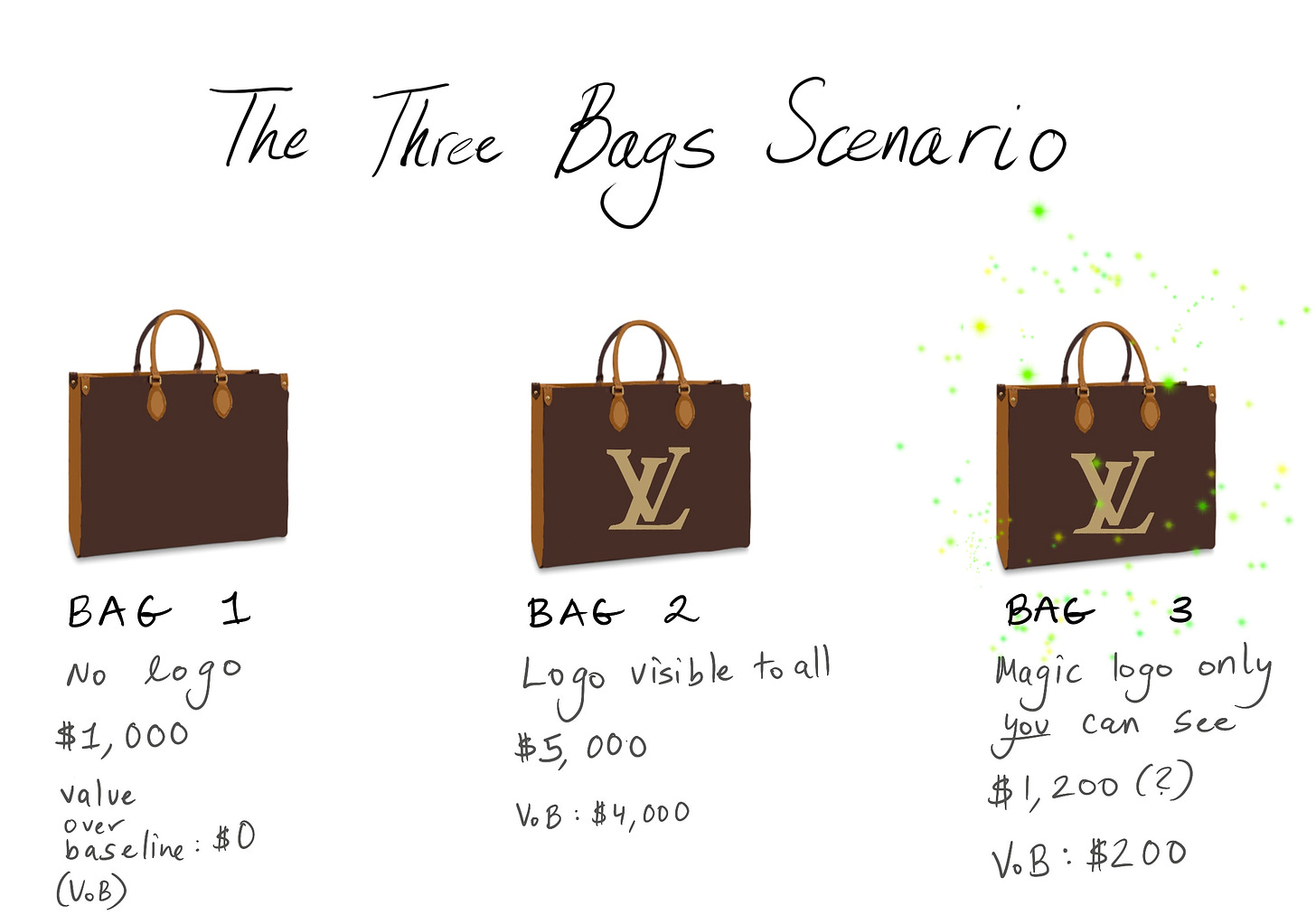

Like few other industries, the luxury space is defined by perception. Certainly, conglomerates like LVMH take great care to use high-quality materials and exceptional craftsmanship. But pricing power derives not from inputs but intangibles. Narrative value explains why one beautiful leather bag might cost $1,000, while an identically-made second bearing the iconic LV logo fetches $5,000.

Acquisitions like that of Clos de Lambray may not explicitly show up in the topline, but they implicitly influence consumer perception of the group and its corresponding brands. Keystone companies like Louis Vuitton, which dates back to the period of Napoleon III, see their positioning fortified through the association with other storied brands. At the same time, new endeavors are burnished by the connection. Modern LVMH brands like Rihanna’s Fenty Beauty feel less like a detached contemporary project and more like part of an established lineage. Within Arnault’s framework for star brands, buying heritage solves the need for a “timeless” quality. And in some respects, the strategy produces an attenuated, distorted version of network effects with each legendary company added, making every other brand more valuable.

While Clos de Lambray may be the most obvious illustration of this approach given its age and relative financial irrelevance, LVMH’s M&A history is littered with generational examples. For those reasonably unfamiliar with the heritage of the acquisitions mentioned above:

Guerlain was founded in 1828, acquired in 1994

Tiffany was founded in 1837, acquired in 2020

Loewe was founded in 1846, acquired in 1996

Moynat was founded in 1849, acquired in 2010

Tag Heuer was founded in 1860, acquired in 1999

Berluti was founded in 1895, acquired in 1993

Rimowa was founded in 1898, acquired in 2016

Loro Piana was founded in 1924, acquired in 2013

Fendi was founded in 1925, acquired in 2001

The list goes on. For a conglomerate founded in 1987, LVMH feels gloriously ancient. Arnault knows that represents money well spent.

Decentralized, artist-led governance

In 2001, just a year after Galliano’s “Homeless” show, Harvard Business Review asked Arnault what he thought when he heard about the designer’s “newspaper dresses?”

Arnault’s response revealed much of what makes LVMH special:

I was shocked, which is good, of course. A new product is not creative—it is not important—if it does not shock when you first see it…

Our philosophy is quite simple, really. If you look over a creative person’s shoulder, he will stop doing great work. Wouldn’t you, if some manager were watching your every move, clutching a calculator in his hand? So that is why LVMH is, as a company, so decentralized. Each brand very much runs itself, headed by its own artistic director. Central headquarters in Paris is very small, especially for a company with 54,000 employees and 1,300 stores around the world. There are only 250 of us, and I assure you, we do not lurk around every corner, questioning every creative decision.

To make magic, Arnault recognizes that artists need the freedom to work. That license starts at the top and filters throughout the organization, informing decisions both big and small.

At the highest level, LVMH is constructed to enable autonomy. The company is divided into six discrete groups, each hosting individual “Houses.”

Each unit can act according to its own culture while still benefiting from the distribution and resources of the parent company. Within each House, creatives drive the vision, whether that is Galliano at Dior or Marc Jacobs at Louis Vuitton.

The extent to which artists can execute their wildest fantasies, in detail, is particularly remarkable. Not only is Galliano permitted to go rogue with daydreams of dereliction, but he’s also entrusted to execute his vision from start to finish, even taking control of product marketing. From Arnault:

The last thing you should do is assign advertising to your marketing department. If you do that, you lose the proximity between the designers and the message to the marketplace. At LVMH, we keep the advertising right inside the design team. With the Dior campaign, John Galliano himself did the makeup on the model. He posed her. The only thing Galliano did not do himself was snap the photo.

LVMH’s approach is as if WarnerBros turned over management of its Pictures Group to Bong Joon Ho or Paramount asked David Lynch to write the copy for his film’s trailers.

The faith in artists is also demonstrated inversely by the relatively low stock LVMH puts in measures like focus groups.

[Y]ou will never be able to predict the success of a product that way [through focus groups]. What a test shows you is limited: whether the product has a potential problem, such as with its name. You may discover that the name of a product is good in English, say, but it means something else in Japanese. Or you can test a perfume and find out that in some part of the world, one part of its formula carries a bad connotation that you have not thought of. But these tests will never tell you if a product is going to be a worldwide success. Take J’adore, the fragrance we released in 1999. Nothing in the tests suggested what would happen; the people in the focus groups said it was fine, just that. But look what happened—according to our estimates, it was among the top three best selling perfumes in the world last year [2000].

Arnault recognizes that not every artist is suited to LVMH, nor will they thrive. Instead, he asks his team to identify creatives with the desire, the vanity, to see their works produced on a global scale. Making such an assessment is an intuitive, cagey process, made more difficult by the artist’s inner-dissembling:

The responsibility of the manager in a company dependent on innovation, then, very much becomes picking the right creative people—the ones who want to see their designs on the street. And that desire inside them is something that you, as a leader of a company, can only sense. After all, most artists don’t go around proclaiming, “I want to be a commercial success.” They would actually hate to say that. And frankly, if you asked them, they would say they don’t actually care one way or another if people buy their products. But they do care. It’s just buried in their DNA, and as a manager, you have to be able to see it there. I know you are going to ask, “How can I see into a person’s DNA, to know if he is an artist with commercial instincts?” So I will answer, it just takes experience. Years of practice—trial and error—and you learn.

LVMH does constrain its talent in one critical way: limiting the size of the canvas. While visionaries like Galliano are free to conjure provocative visions and see them out, down to the minute details, they are allowed to play with just part of the business. Per Arnault, just 15% of a House’s business should come from new products on an annual basis:

We do not put the entire company at risk by introducing all new products all the time. In any given year, in fact, only 15% of our business comes from the new; the rest comes from traditional, proven products—the classics.

Once again, Arnault demonstrates the subtle balance LVMH strikes, championing wild creativity and autonomy while mitigating risk.

Securing the supply chain

Louis Vuitton’s iconic “Petite Malle” purse costs $5,800. Given the price, consumers rightfully expect quality.

On that front, LVMH’s commitment cannot be questioned. Under Arnault, the obsession with high caliber materials and craftsmanship has been taken to psychotic new levels. Such moves serve to bolster the brand — many of LVMH’s supply-chain initiatives are undertaken very publicly — they also ensure product excellence.

LVMH’s pursuit of quality begins by ensuring it has the best possible materials. The company goes to great lengths to make that happen, from buying suppliers outright, striking partnerships, or spinning up in-house operations.

LVMH’s acquisition of Loro Piana, a cashmere producer, has largely been perceived as a way to certify the conglomerate’s more prominent brands have access to the materials they need. Meanwhile, Arnault’s team have gone about forging partnerships with Swiss and African fragrance suppliers, bought acres of land in France’s perfume region, snapped up tanneries throughout Europe, and acquired Johnstone River, a crocodile farm in Australia. In 2017, LVMH partnered with eyewear manufacturer Marcelin to create Thelios, an entity designed to bring the latter’s expertise into the former’s processes.

Once LVMH attains the best materials, products are constructed with the utmost care and skill. One purse like the Petite Malle may take 1,000 discrete actions to complete, and as Arnault notes, “we plan each and every one.” LVMH has gone to remarkable lengths to make sure it has a workforce capable of executing even the most esoteric skills. Tech commentators are fond of imagining a future of higher education run by the world’s biggest companies, designed to develop workers for eventual employment. How long until we see a Google State or a Facebook College?

Meanwhile, The University of LVMH already exists; it is called L’Institut des Métiers d’Excellence (IME). Founded in 2014 in partnership with other universities, IME is a vocational program that teaches students the “savoir faire” necessary to make jewelry, wine, couture, or some function within the Arnault empire. Students receive both practical and theoretical tutelage and get exposure to the operations at one of the company’s Maisons. As of 2020, 900 students have passed through the program, with the majority attaining employment at LVMH or a partner organization. Though these represent reasonably small numbers in the scheme of a six-figure workforce, it nevertheless sets up the structure to benefit from an ongoing, trained workforce. Simultaneously, LVMH earns brand affinity — implicit in the establishment of the IME is the idea that not just anyone can show up and start fashioning a Louis Vuitton bag; training is required.

Once artisans have constructed the object from elite materials, the final step of production is reached: torture. To guarantee the longevity of its creations, LVMH puts its wares through arduous testing:

Before we launch a Louis Vuitton suitcase, for example, we put it in a torture machine, where it is opened and closed five times per minute for three weeks. And that is not all—it is thrown, and shaken, and crushed. You would laugh if you saw what we do, but that is how you build something that becomes an heirloom. By the way, we put some of our competitors’ products through the same tests, and they come out like bouillie—the mush babies eat.

As with the rest of LVMH’s supply chain, this step preserves quality while building brand mythology.

Managing generational change

As Arnault makes clear, timelessness is not enough — star brands have to be modern, too.

Under his leadership, LVMH has shown an aptitude for finding the right time for reinvention. The company has done this by reenergizing old brands and buying new ones.

While not all of Arnault’s appointments have proven astute — McQueen at Givenchy was a disaster — several of his picks redefined the brands they helmed. Though his ignominious departure sullied Gallino’s tenure at Dior (dismissed after an anti-semitic rant), he undoubtedly revitalized the House, positioning it as an adventurous couturier. In the wake of Galliano, Dior eventually tapped Raf Simons, who “gave Dior’s rich, romantic legacy...a modern edge, and without the drama and personal excess of his predecessor.” Between his start in 2011 and 2015, Simons oversaw a 60% increase in sales.

As creative director, Marc Jacobs transformed Louis Vuitton from a luggage-maker into a fresh, lively fashion brand while increasing revenue 4x. Former Bergdorf CEO Rob Frasch remarked:

They created fashion excitement. It wasn’t a formula. Something new was going to happen every season. Marc wasn’t in a box like some brands are.

Nicolas Ghesquière succeeded Jacobs in 2013. His first show was praised by the New York Times “for its modernity, its clarity, its decency – and its respect for women.” In the years since that debut, Ghesquière has further rejuvenated Louis Vuitton by courting pop-culture phenomena like Stranger Things, embracing sneakerheads, and even remaking that iconic Petit Malle purse.

As we know from Arnault, it is no coincidence (and not a given) that each appointment has succeeded by bringing the “new” and “modern” to their historic Houses.

Intriguingly, LVMH seems to be amid yet another renewal. Last year, Givenchy’s creative director Ricard Tisci was replaced by Matthew Williams. Not only is Williams the founder of the Alyx, a brand I would, in my ignorance, describe as “minimalist hypebeast,” he designed for Kanye West.

Another former Kanye attache has been granted stewardship over Louis Vuitton’s menswear division. Whatever one thinks of Virgil Abloh and his conviction that creating a new design requires altering an old one by just “three percent” — (hint: it looks a lot like plagiarism) — he has undoubtedly captured the zeitgeist through collaborations with Nike and label Off-White. As with Galliano’s 2000 collection, controversy may only add to the piquancy of his creations for the Maison.

Perhaps the most striking example of regeneration is LVMH’s joint venture with Rihanna. Despite having a preexisting relationship with MAC Cosmetics, Arnault successfully convinced the Barbadian icon to create her beauty line with Kendo Holdings, the conglomerate’s white-labeling division. Per the 2017 deal, Rihanna holds 49.99% of Fenty, with LVMH owning the remaining 50.01%. In announcing the arrangement, Rihanna highlighted the “unique opportunity to develop a fashion house in the luxury sector, with no artistic limits.”

LVMH is reported to have paid just $10 million for co-development rights. In 2019, the brand’s cosmetics line was valued at $3 billion. Arnault may have another star on his hands.

Guarding the Legacy

A collector of family businesses will know better than most just how often Time ends a dynasty. To preserve his legacy at LVMH, Arnault will need to embrace digital luxury, quash infighting between his children, and keep luxury conglomerate Richemont from falling into the hands of other rivals.

Digitally native luxury

“We need to be strong on the digital front, but we must not trivialize our products.”

To retain the prestige of its brand, LVMH has deemphasized e-commerce, focusing on a retail experience, and steering clear of offering items on platforms like JD.com or Tmall, both crucial to access the Chinese online shopper. (Interestingly, Louis Vuitton does have a strong following on Japanese super-app LINE, providing digital access to a critical market.)

Coronavirus has changed the calculation. Though the conglomerate took a hit last year with revenue falling 17%, e-commerce performance was a bright spot, with in-house platform 24S seeing robust growth. Chief Financial Officer, Jean-Jacques Guiony, spoke to that progress, while at the same time emphasizing the challenge the company faces in Asian markets:

Our 24S platform did quite well...We wouldn’t call this a full and lasting success yet, but it’s encouraging…

There is no such thing as a Chinese traveler for the time being. We hope that we shall be able in due course to extract as much value as we can from the Chinese customers by enabling them to shop where they want to shop. But for the time being there are serious constraints as to their ability to shop outside China, and this is obviously a weight on the growth for coming quarters.

Though the fading of the pandemic should bring foot traffic back to stores, LVMH should use this opportunity to prioritize a proper omnichannel strategy. That doesn’t mean listing on platforms with insufficient cache; rather, Arnault should aggressively capitalize 24S (it needs to catch up on mobile) while looking for other promising digitally native additions.

The company missed a trick by losing Yoox Net-A-Porter to Richemont for $3.4 billion, allowing the same competitor to secure a joint-venture with Farfetch (more below). It should ensure it does not make a similar mistake again. Moda Operandi might make an attractive target — though the platform raised $345 million in capital and was once considered a preeminent player, it has undergone a turbulent few years, churning through CEOs. Still, the company holds some name brand recognition and has accumulated a luxury customer base, used to buying online.

Should Arnault wish to shop in the luxury section of the M&A markets, he might turn his thoughts back to Farfetch. With a current valuation of $17.1 billion, buying $FTCH would represent the luxury market’s largest-ever acquisition, outstripping LVMH’s $16.2 billion purchase of Tiffany’s last year. Farfetch’s relationship with Richemont and JD.com would complicate matters, but Arnault has a long record in trying (and often pulling off) convoluted acquisitions.

Making physical goods available to buy online is not enough, however. While taking e-commerce seriously is a good start, LVMH needs to position itself to become the default purveyor of digital luxury goods.

In Modern Value, I argued that the pushback against the ostensible frivolity of NFTs missed something important:

Increasingly, the internet is where we generate and exercise status. Our most significant accomplishments, wittiest thoughts, and lustrous photos are all shared online to reflect and create prestige. This might be aimed at a small or large audience, but the core desire to demonstrate value and enhance social rank is the same.

Luxury goods are valuable in part because we get to show them off.

Imagine three bags. All are made out of the same gorgeous leather material and constructed immaculately.

The first bag bears no logo.

The second bag brandishes Louis Vuitton’s “LV” for all the world to see.

The third bag is a miracle. It has the same “LV” printed on it, but only you can see it. To everyone else in the world, the third bag looks like the first one; to you, it looks like the second. Even more magically, every time you try and tell people that it’s a Louis Vuitton bag, the air swallows your words.

If a buyer was informed of the properties of each bag, how much would they be worth? Perhaps Bag 1 would be worth $1,000, priced according to the quality of its materials. Bearing its unmistakable status symbol, Bag 2 might be worth $5,000. But what about Bag 3?

Arguably the final bag might be priced almost the same as Bag 1. How much is it worth to someone to know they own a Louis V bag but not be able to exhibit it? An extra 10%? Maybe 20%?

The Three Bags Scenario illustrates a rough truism of luxury goods: value above the baseline correlates with the number of people to whom you can show it. (The perceived status of audience members is also important, but we’ll avoid the weeds.)

This hammers home why LVMH must proactively experiment with digital clothing; no arena provides a larger audience than the internet. Already, the company has shown admirable openness, releasing a League of Legends skin and Final Fantasy collection. To take these efforts to the next level, Arnault should purchase his first “very online” atelier.

The Fabricant is a digital-only couture brand that creates, among other things, apparel NFTs. The company created “Iridescence,” a nacreous cybernated garment that was the first “dress on the blockchain.” It sold for $9,500.

In addition to owning the NFT as a piece of art, the purchaser can apply the dress to photos, like a filter. In describing The Fabricant’s and the opportunity to design digitally, CEO Amber Jae Slooten noted:

I wouldn’t want to encourage brands to simply copy their physical items. I would encourage them to go beyond their physical reality. For instance, we designed one shoe that was a flaming shoe. You can create all kinds of digital couture looks that could never exist in real life.

LVMH is a conglomerate that has always championed unfettered expression. It should move quickly to ensure it understands how to bring that artistry online.

Avoiding a filial free-for-all

If the Arnault/Chevalier/Racamier battle royale was Shakespearan in its intricate machinations, the coming skirmish is straight out of Succession.

Arnault has five children from two marriages; four of them work at LVMH.

The eldest, Delphine, is EVP at Louis Vuitton. Next comes Antoine, CEO of shoemaker, Berluti. Following him and just 28 years old is Alexandre, CEO of the newly acquired Tiffany. Finally, there is Frédéric, named CEO of Tag Heuer last year at the age of 26. (Jean, only 23, recently graduated from Imperial and is headed to MIT. His fourth-year project focused on “wristwatch timekeeping” and was sponsored by Tag Heuer.)

Despite being one of the most brazen examples of nepotism, Arnault’s heirs may soon cause a problem. With the pater familias 72 years young, succession seems likely within the decade. Who is best poised?

A case can be made for almost any of the siblings. In her role at Louis Vuitton, Delphine oversees one of the company's largest profit centers and highest-profile roles, but Antoine is considered the more expressive executive. “Antoine is more extrovert,” one analyst noted, "Delphine can have a very important role, but more in the way of a shareholder or chairman, not a manager. Antoine can be the face of the group." Alexandre should not be counted out, having already helmed Rimowa and now being handed the reins of LVMH’s newest jewel. Though young, the French press have suggested Frédéric is his father’s favorite.

So far, Arnault has succeeded in elevating his children without creating rifts. By giving each child a meaningful division to manage and pairing them with an experienced executive, all are undergoing both audition and apprenticeship. While that might result in an obvious successor, accepted unanimously, it's just as easy to imagine claims to the throne remaining relatively equal. Once the Elder Arnault steps down, that might descend into all-out war.

To prevent disarray, Arnault should positively identify his successor within the next five years, having them take over operations piecemeal before claiming the CEO role. That would allow any initial infighting to occur under his watch, rather than allowing such conflict to occur in a power vacuum.

Richemont

Richemont is in play. The Swiss luxury conglomerate boasting brands like Cartier was reported to have turned down an “informal offer” in January. Still, with CEO Rupert aging and no clear successor in place, it looks like a matter of time before the group is under new ownership. LVMH should do everything possible to absorb the company; it must make sure it stays out of the hands of Kering.

Founded in 1988, Richemont has performed admirably since inception but has nevertheless lagged behind its larger rivals. As mentioned earlier, LVMH has a market cap of $376 billion, while Kering comes in at $81.4 billion. Richemont is the junior player with a $58.45 billion share. That has historically put the company in a challenging operational situation — fighting off deep-pocketed adversaries — but now places it in an enviable selling one.

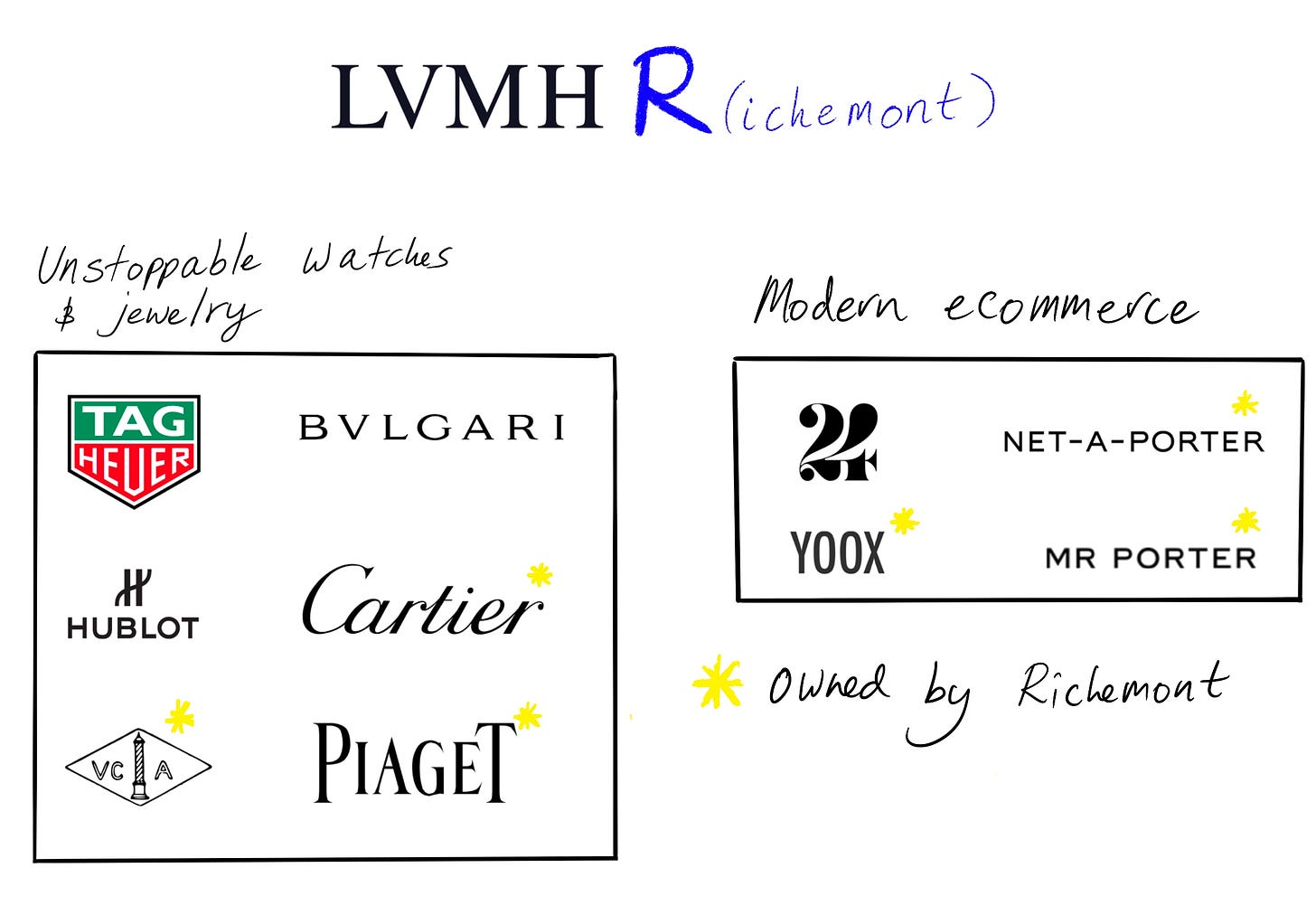

Though some have argued a Richemont-Kering union would make more sense given the former’s substantial jewelry assets and the latter’s apparel brands, an LVMH partnership would be even more compelling to investors. Not only would LVMH bolster its Watches & Jewelry division by snagging Cartier, Van Cleef & Arpels, Mont Blanc, and Piaget, it would address the business’s online vulnerabilities.

As alluded to earlier, Richemont holds interests in the outstanding luxury e-commerce players, having bought Yoox Net-A-Porter and secured a position in Farfetch. Picking up those assets would turn LVMH from a comparative e-commerce laggard into a leader, guaranteeing Arnault’s shop had not just the best brands but the most extensive, modern distribution system.

Just as importantly, taking Richemont off the table would curb Kering, removing its best shot at closing the gap to LVMH. And lastly, though LVMH’s executives will not care a jot for the narrative symmetry, such a monumental merger would prove a fitting coda for Arnault’s reign. What began with war could end with a 100-year peace.

“Individuality will always be one of the conditions of real elegance.”

Those words come from Christian Dior, the man behind the atelier that Galliano would shock with 54 years later. Dior’s expression is an apt depiction of the heart of LVMH, fundamental to what animates it artistically and economically. It is a vast and sprawling monument to creativity and yet as ruthless, as delightfully cold-blooded as the most mercenary enterprises.

It is, in Arnault’s paradigm, a star, in and of itself. For what is a star but something impossibly beautiful that will burn to death any who dare come to close.

The Generalist’s work is provided for informational purposes only and should not be construed as legal, business, investment, or tax advice. You should always do your own research and consult advisors on these subjects. Our work may feature entities in which Generalist Capital, LLC or the author has invested.