Modern Meditations: Caleb Watney

What DOGE should do, the potential in far-UV, and how billionaires should spend their money

🌟 Hey there! This is a free edition of The Generalist. To unlock our premium newsletter designed to make you a better founder, investor, and technologist, sign up below. Members get exclusive access to the strategies, tactics, and wisdom of exceptional investors and founders.

Friends,

The Irish playwright George Bernard Shaw summed up the nature of progress with characteristic clarity: “Progress is impossible without change, and those who cannot change their minds cannot change anything.”

Few people embody the spirit of those words quite as much as Caleb Watney. In 2021, he and Alec Staff founded the Institute for Progress (IFP), a non-partisan think-tank focused on the levers of innovation. In a little over three years, the IFP has become a compelling producer of ambitious, intelligent, commonsense policy proposals. Among its key issues, the IFP champions the need for America to attract more high-skilled immigrants, improve our current scientific processes, and build better infrastructure. It is a fundamentally vital, agentic organization in a category that often favors the moribund and uninspired.

Given IFP’s consistently rigorous, high-quality thinking, I was extremely excited to interview Caleb and wander his many idea mazes. It also felt like a fitting moment, as tech’s most powerful (and polarizing) characters prepare to decamp to the IFP’s hometown of D.C. in a quest to remake the American government and reignite global progress.

In today’s interview, Caleb and I discuss what the Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE) should focus on, the R&D investments that could protect against biological threats, the modern era’s information dynamics, and the high-variance timeline we live in.

To hear more from the world’s most interesting thinkers, subscribe to our premium newsletter Generalist+. For $22/month, you’ll unlock private correspondences with luminaries like Reid Hoffman and Vinod Khosla. You’ll also get access to tactical guides and startup database designed to make you a better investor and technologist.

Building in the age of AI: Startup lessons for early-stage growth

In an era where AI is reshaping how businesses operate, the journey of building an early-stage startup has never been more dynamic—or complex. How do founders navigate finding product-market fit, delegation, and scaling, all while adapting to technological innovations?

Join on January 14 at 3 pm PT for a fireside chat with Christina Cacioppo, CEO and Co-founder of Vanta, and Eric Ries, author of The Lean Startup and Founder of LTSE, as they explore the journey of the modern startup founder.

Eric and Christina will discuss:

Learnings from their own experiences

How the principles of “founder mode” and lean methodology intersect

The ways that today’s AI-driven landscape shapes early-stage growth and startup success

Which current or historical figure has most impacted your thinking?

I find myself more influenced by contemporary thinkers, as they’re actively responding to current world events and trade-offs. Watching someone think through issues in real time makes it easier to internalize their mental models.

One figure who’s definitely influenced my thinking is Tyler Cowen from George Mason University. He was a big part of why I chose to go there to get my Masters in Economics. I made sure to take his class while I was there and it was just excellent. It was formally about industrial organization but was also just a chance to experience his style of thinking in person, like doing a live-reading of Marginal Revolution every week.

Over the years, I’ve cultivated a kind of “mini Tyler” that sits on my shoulder, helping me think better. He’ll question what I read, for example, examining the trade-offs behind seemingly simple policy proposals, considering who gains or loses status in culture war discussions, and emphasizing the importance of state capacity, especially for those who care about market functionality. He’ll even help me make mundane decisions, like choosing the right restaurant and what heuristics to use when ordering.

In founding IFP, Tyler’s been an incredible ally. He’s provided advice, helped with connections, and assisted us in thinking through various policy issues. He’s a tremendous person to have in your corner.

What are you obsessed with that others rarely talk about?

I’m obsessed with the mechanics of making government work better. Government efficiency is in the news a lot lately with DOGE, but there are really several different conversations happening. Some focus on cutting waste, fraud, and abuse, for example. That makes sense in certain areas like Medicare fraud and defense procurement. But I worry we’ll get too fixated on this, doing things like questioning every single detail of NIH grants. Ultimately, I don’t think we’re going to squeeze a lot of juice out of that.

I’m more excited about initiatives that improve government hiring. How do we make it easier to hire great people? That’s one of the most important questions we could be asking. There are some really basic, mundane ways that the government is broken and some in-the-weeds solutions we could be using more aggressively.

For example, The Office of Management and Budget has this thing called “direct hire authority” that allows it to bypass the usual bureaucratic process for positions that rely on hard-to-find skills. In the past, for example, it’s been successfully used to fill cybersecurity positions. Why aren’t we doing that more proactively for other scientific and technical talent?

Another blocker to getting great talent into the government is pay. It’s kind of crazy how little we pay civil servants. The current system relies on a sort of Faustian bargain: civil servants get paid a fraction of what top performers in the private sector can earn, but they get really strong protections, making them impossible to fire. You end up with the worst of both worlds, where the most talented, ambitious people are deterred from applying in the first place. Those who do pursue that path are stifled and stuck working with low performers who can’t be moved out. There’s an acronym I’ve heard used for these people who spend 20 years without doing much: “RIP” or “retired in place.”

Government procurement is another area that needs improvement. How do we buy stuff better? The traditional process is a total nightmare. But again, there are alternatives that have been used in the past. DARPA, the DoD, and NASA have all used something called “other transactions authority” previously, which allows for more creative, ambitious, well-scoped agreements. NASA famously used it to give SpaceX the capital necessary to resupply the International Space Station.

It’s these kinds of nitty-gritty solutions that I get really excited about. They exist – they’re just underutilized.

Will DOGE tackle these problems? Or will it just focus on cutting costs and creating media firestorms around things that don’t really matter?

I don’t know yet. In general, my feelings about DOGE mirror my feelings about the entire administration: we’re in a high-variance timeline. Whether that’s good or bad depends on how broken or stable you thought the previous equilibrium was. I have some friends who believe our previous institutions were fundamentally broken and needed someone to come in and change things – from that perspective, it’s easier to be optimistic.

But it’s also easy to underrate how much good has come from the stable operation of institutions like the NIH and their contribution to biomedical progress in the United States. So, I find myself optimistic in some ways and pessimistic in others. I’m interested in how we can help ensure we end up on the right side of this variance.

What craft are you spending a lifetime honing?

Persuasion. But I want to distinguish between how we often view persuasion and what I mean.

Sometimes, people have a view of persuasion that’s adjacent to pick-up artists or something. It’s the idea of, Let me teach you these three tricks to fool your opponents or win your debate. This is a very Ben Shapiro-esque version of persuasion and one that I’m uninterested in. I think it’s shallow and less likely to actually persuade someone.

Learning how other smart, thoughtful people think about an issue, understanding the philosophical commitments they have and the values they prioritize, is central to any attempt at genuine persuasion. This is the habit I’m constantly trying to inculcate in myself. Whenever I see something I disagree with from someone I know is smart and thoughtful, rather than getting mad or assuming bad intentions, I ask myself, “What is the best possible reason, the most charitable reason, they might be thinking this way?”

When I start from that place, I find it much easier to navigate the world and also to persuade that person.

What experiment would you run if you had unlimited resources and no operational constraints?

When you look at Nobel Prize winners, it’s almost absurd how often they’ve been mentored by other top scientists. You see the same pattern with Howard Hughes Medical Institute principal investigators and winners of other major scientific prizes – at very high rates, these people aren’t coming out of nowhere. They typically have been mentored by a prize winner or another giant in their field. The result is heavy concentration at the top of the scientific industry.

This phenomenon raises a crucial question: is this a treatment effect or a selection effect? Maybe top scientists have a special knack for recognizing scientific talent. If that’s true, these talented individuals would have been just as successful if you’d identified them through some other means.

Alternatively, maybe there’s something unique about working hand-in-hand at the lab bench with a Nobel Prize-winning biologist. It could be this close integration that allows you to learn, at a deep, tactile level, what it means to be a great scientist and how to think ambitiously.

Both explanations seem plausible to me, and the answer has massive ramifications for how we should structure and incentivize our science funding ecosystem.

If I could run a giant experiment, I would want to randomize who does talent selection versus mentorship among top scientists for the next young cohort of scientific talent. The goal would be to figure out the breakdown between selection and treatment effects. The answer would be tremendously important in structuring our scientific institutions.

What is the most significant thing you’ve changed your mind about over the past decade?

A decade is a long time. The single biggest shift in my thinking has probably been around market failures in R&D spending. Like many people, I went through a libertarian phase when I was younger – I was a big believer in markets’ ability to identify promising opportunities and invest in them, and that government intervention often did more harm than good.

I still believe strongly in the power of markets, but I’ve realized it’s precisely because markets and market actors are rational that they don’t invest enough in R&D. As you learn more about how science and R&D work, you see some crazy things. For instance, when the NIH invests in a scientific field, they’re just as likely to create a breakthrough in a completely different field because science is so incredibly unpredictable. That makes it hard for private actors to make rational investments. The development of mRNA vaccines, for example, was only possible because of basic scientific work that the NIH and other public bodies did for decades.

Google’s investment in Waymo is an anomaly. I’m thankful that Google has been willing to take this really patient investment approach toward self-driving technology for almost twenty years.

If Google wasn’t essentially a founder-controlled company, I think it’s plausible they would have given up on it already. And frankly, if you had the ability to go back in time and tell Google how long and how much money it would take before they started to see promising results, I’m not sure they would have done it. Like many people in tech at the time, I think they felt self-driving was much closer than it turned out to be. But now, that investment looks likely to be a huge benefit to the rest of society.

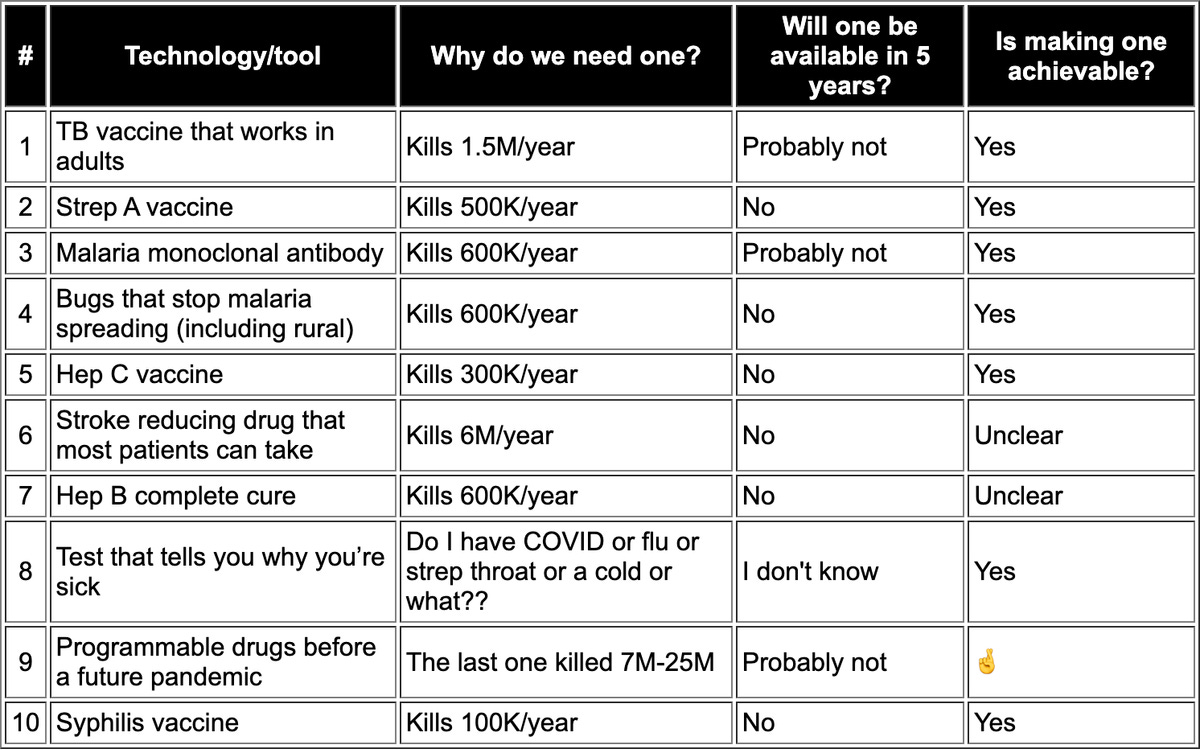

Because market actors tend to invest rationally, plenty of promising initiatives are left unfunded or undeveloped. My friend Jacob Trefethen wrote a great post called “10 Technologies That Won’t Exist in Five Years.”

It enumerates neglected diseases we have the technological capacity to create vaccines for and that are killing millions of people around the globe. But because those people are in Sub-Saharan Africa or other places with low buying power, it’s difficult for the market to price that in. These are instances that demonstrate the importance of public investment.

Beyond the examples in Jacob’s post, there are a couple of other areas I’d love to see public investment in:

First, I’d like to see a big push around mechanistic interoperability in AI. We don’t understand well enough how large language models make decisions – it’s a big question mark. Companies like Anthropic have been making useful investments in this space, but I think we need something of the scale and ambition of the Human Genome Project to map this out.

Second, I’m optimistic about the potential for far-UVC light as a disinfectant. Famously, UV light is a disinfectant. It can kill airborne viruses and is sometimes used for cleaning. The trouble with it is that it damages human skin.

However, there’s a part of the light spectrum called “far-UVC”, which has shorter wavelengths that can’t penetrate human skin and are a lot safer. Though we’re still in the testing phase, far-UVC seems to have the same disinfectant and virus-neutralizing properties, which could be really valuable. You imagine it being deployed in airports, gyms, schools, and similar places where viruses typically spread. Not only would this be useful for pandemics, but also a lot of mundane public health. Wouldn’t it be great if our seasonal cold and flu season was one-tenth as bad as it currently is? If this works, it could save a lot of lives and misery.

What piece of art can you not stop thinking about?

There’s the actual answer to this and the more sophisticated answer. If you’re asking me today, it would probably be Wicked. I saw it recently, and the soundtracks are playing in my head again and again. It’s not fine art, but it was very enjoyable and worth seeing.

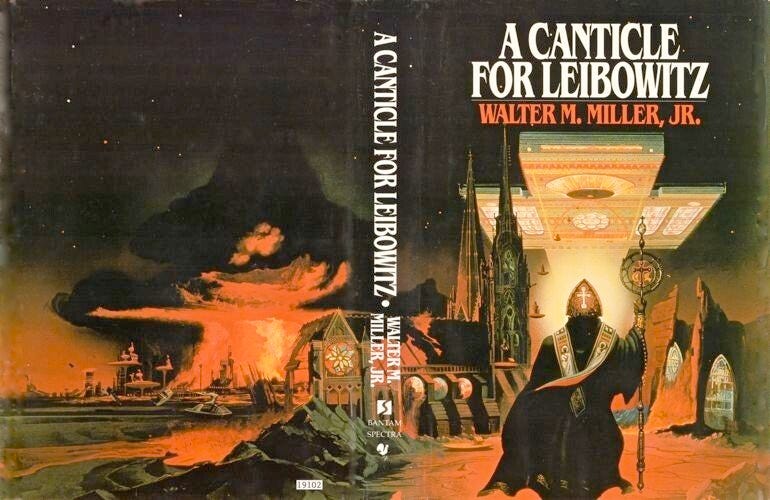

On a longer-term basis, I’ve always loved the sci-fi book A Canticle for Leibowitz. It’s this 1959 post-apocalyptic novel by Walter Miller that tells the story of an order of monks.

The world has been destroyed by a nuclear disaster, and this one little abbey has taken it upon itself to preserve the remnants of human knowledge and try to prevent another Dark Age. The monks themselves don’t understand a lot of the knowledge they’re preserving and treat them like holy relics. They’ll have illuminated manuscripts of circuit boards that they’re holding onto for future humans to make use of.

The novel shows you the abbey in three different periods, each one about 200 years apart, as civilization rebuilds around it.

It’s a fascinating look at the cyclical nature of human civilization, the rise and fall and rebirth. I also think it serves as a useful reminder that progress is neither inevitable nor irreversible. It’s a call for stewardship of our technological capabilities, which is very relevant today. There are religious themes that resonate with me as an Anglican. Lastly, it’s just a beautiful work of literature, where every page is well-written.

What tradition or practice from another culture or time period do you think we should widely adopt?

We should adopt Renaissance-era patronage practices in the arts and sciences. Great geniuses like Michelangelo were sponsored by wealthy individuals willing to take a shot on crazy, out-there ideas.

At a high level, I think our current billionaire class is very unambitious with their philanthropy. A lot of them are just sitting on their money, not doing anything with it. Given normal market returns, they could give away 5% a year and maintain their same level of wealth. Famously, of course, you cannot take your money with you when you die, and the research literature on passing it onto your children suggests that’s an unproductive path that produces unhappiness in the recipients.

A good critique is to say, “Well, there are a lot of effective charities you can donate to.” As someone who runs what I hope is an effective charity, I’m obviously supportive of that message.

But there are also much more eclectic things you can do. You could build a massive castle in Nevada. You could try to terraform a part of Greenland. There are so many mega-projects that could be undertaken.

Convergent Research has created an organizational model called a “focused research organization” (FRO), which I think is really promising. These are philanthropically supported structures built to fund really ambitious technical, scientific projects with an intended wind-down date. You might create a FRO to develop a better set of machine tools to map the human brain. That’s something that it’s hard to get an NIH grant for and also doesn’t have a large commercial market. The best solution is something philanthropically funded.

Every billionaire worth their salt should have at least one FRO of their own that they’re really excited about. There are so many cool, creative, scientific projects out there that are not being funded, and a whole class of very, very wealthy people sitting on their money, not really doing anything. That’s a mismatch.

If you had the power to assign a book for everyone on Earth to read and understand, which book would you choose?

Revolt of the Public by Martin Gurri is a book I think about a lot. It’s an exceptional framework for understanding the modern age’s information dynamics.

Gurri was a former CIA analyst who saw how movements like the Arab Spring played out with social media. The primary thesis of his book is that the elites and gatekeeping institutions of the modern age are, in some sense, just as corrupt, broken, and fallible as they’ve always been. But their failure is much more legible now because of the internet. That shift has created a fundamentally different relationship between the public and its institutions.

I’m a Kansas City Chiefs fan, so I like to use the example of NFL referees. Online, you find that people are convinced that refereeing is as bad as it’s ever been and that their team, in particular, is maligned by the officials. You’ll find someone posting a Twitter thread of 30 separate incidents where a particular ref blew borderline calls against their team and they’ll think the only possible explanation is bias and corruption.

In actuality, I think refereeing is probably better than it's ever been, but no one’s going back to the games of the 1970s and cataloging every referee’s decisions. It’s easier than ever today to compile a plethora of anecdotes that begin to look like evidence without actually conducting a rigorous statistical analysis.

This example is part of a larger phenomenon that’s happening across our institutions. As Gurri synthesizes it, the overriding voice of the public is one that says: No. No, we don’t like what is currently happening but we don’t have a proactive agenda to replace it with. Just tear down the current thing.

I think that’s the single best explanation for what is happening not just in the US but across the world. It’s this anti-incumbent bias. Historically, the incumbent used to have an advantage; if you were the sitting president, you were more likely to keep your spot in the next election. Now, it looks like that’s reversing – the advantage is in being perceived as an outsider ready to tear down the current system. The internet and the information dynamics around it are key parts of why that’s happening.

What will the next generation do, or use, that is unimaginable to us today?

The other day, I was reflecting on the fact that when you look at famous sci-fi books focused on the far future, they often find a way to write AI out of the story. In the Dune universe, for example, you have the Butlerian Jihad, where humanity turns against AI and decides not to use it. The Foundation universe has robots but doesn’t really have super-intelligent AIs. There are other books that seem to have something like the Butlerian Jihad.

I think the reason for that is because it’s really, really hard to know what the future will look like with AI, and so from a storytelling perspective, it’s easier to write it off.

All of this is to say that I suspect it will have something to do with AI, but I don’t know what exactly. It feels like we’re on the cusp of a dramatic step change in how this technology functions and how our civilization thinks about collective intelligence that sits outside our human brains. I have already forgotten where things are now because I can rely on Google Maps, and I think we’ll see more of this outsourcing of our cognition to an external software stack. AI’s another step in that direction, but it will be a much bigger deal.

What risk are we radically underestimating as a species? What are we overestimating?

We continue to underestimate biological threats. At a macro-level, humans have evolved to be very robust in our particular biological environment. We know roughly the categories of viruses we can be exposed to and have developed immune responses to them. Think about War of the Worlds – the alien invaders come to Earth and end up being wiped out by the common cold because they’ve never been exposed to it before.

We’re developing the ability to introduce very different biological agents into our environment through synthetic biology. That has a lot of exciting applications – there are so many really cool things we can do on a pharmaceutical level, but it may also be a threat to civilization as it exists. Pandemics are one version of this, but not the only one.

It’s possible to avoid these risks or build better defenses, but it’s going to require proactive investment. We need to think about building better countermeasures, vaccine platforms, and detection systems so that we know when a novel virus is running through the human population.

I’ve been concerned by the lack of lessons learned from COVID. You might have thought it would have resulted in this big wake-up call, but instead, it’s been amalgamated into our larger culture war.

Disinformation and misinformation are overrated in my view. Obviously, it’s something that happens and you do see coordinated attempts to signal boost things that are false. But I do think that things are a lot thornier than media gatekeepers and fact checkers portray them to be. It’s often the case that politicians are slightly exaggerating or saying things that aren’t fully clear – there’s much more of a spectrum.

It’s, of course, good to push back on false claims. But the idea that we need to protect our naive population from dangerous facts or falsehoods is an overrated concern. Our institutions don’t have a monopoly on truth and, in fact, a critical part of scientific inquiry is being open to suggestions from the outside.

Lastly, I think it’s a lot harder to persuade people than we think, especially when it comes to their core beliefs. Facebook ads aren’t going to do a whole lot in the grand scheme of things.

What’s an underappreciated corner of the internet?

I’m a big fan of Congressional Research Service Reports. When Congress wants to know how a part of the government operates, it will send a request to CRS. All of these reports used to be private, but they’ve been made public over the past couple of years. There’s a huge back catalog of fascinating, deeply researched, technical, non-partisan analyses. It’s the single best place to start when you want to know how the government actually works.

My colleague Santi Ruiz also writes a newsletter that I think is excellent, called Statecraft. He interviews policymakers, digging into how stuff gets done. Between that and CRS, I think you can get a strong picture of how Washington operates.

How will future historians describe our current era?

It will be remembered as the age in which we mastered technology – or we did not. Between AI, CRISPR, mRNA, and even things like GLP-1 agonists, the baseline environment humans live in is changing dramatically.

Historically, human civilization has been pretty limited in both the upside and downside but as our capabilities are growing, that variance is too.

It’s good for us to aspire toward mastery of these technologies, which means using them in the ways we intend and getting the results we intend. If we do, we could end up in a much better world. But it’s possible the result is a much worse one.

The Generalist’s work is provided for informational purposes only and should not be construed as legal, business, investment, or tax advice. You should always do your own research and consult advisors on these subjects. Our work may feature entities in which Generalist Capital, LLC or the author has invested.