Modern Meditations: Josh Wolfe

The founder of Lux Capital discusses entropy's role in venture capital, the importance of nuclear energy, and Charlie Munger.

Brought to you by Composer

Strategy is the antidote for uncertainty.

We begin 2023 caught in the fogs of inflation, a potential recession, and volatile markets. But what if it was possible to turn uncertainty into opportunity?

The tender state of the stock market over the last year has given retail investors some cause for concern. That doesn’t mean you should sit on the sidelines and wait for the market to jump back.

Don’t leave your money up to impulse. Find the perfect algorithmic strategy for your portfolio.

Composer makes it possible to utilize advanced algorithmic strategies that safeguard your money with logic and data. By responding directly to live market trends, your portfolio gets a fresh kick of financial agility and reacts appropriately. Simply pick from a variety of automated strategies, test it, and start seeing better returns on your investments. No code required.

Actionable insights

If you only have a few minutes to spare, here's what investors, operators, and founders should know about Josh Wolfe’s meditations.

Three spaces. Though Lux Capital invests across multiple categories, Josh Wolfe is currently focused on three “spaces”: inner space (biology), outer space (aerospace and defense), and latent space (the magic of AI models).

The magic of interdisciplinary thinking. Great ideas and big opportunities are often found at the interstices between fields. Wolfe draws on fields like myrmecology (the study of ants) and physics to inform his work as a venture capitalist. The work of E.O. Wilson introduced Wolfe to this kind of thinking.

Fiction’s transformative power. For much of his adult life, Wolfe read biographies and other works of non-fiction. Recent years have increased his appreciation for fiction, and its ability to reveal more fundamental human truths.

The threat of the “environmental” movement. Some players in the environmental movement do their cause more harm than good, in Wolfe’s view. Those that advocate for austerity and de-growth inhibit capitalism’s ability to solve such problems. Overlooking nuclear energy is another frequent mistake.

Mounting political tension in Africa. We may wish to pay closer attention to the actions of great powers in Africa. While China builds influence through the Belt and Road initiative, Russian mercenary groups are sewing discord. When combined with other risks, these maneuvers may create the conditions for conflict.

This interview is part of the Modern Meditation series, where we ask the most interesting people in tech non-obvious questions. We hope to bring new aspects of their personality and processes to light.

When I first conceived of Modern Meditations, one of the names I had in mind was Josh Wolfe. As co-founder and Managing Partner of Lux Capital, Josh has invested in some of the most remarkable companies of the past decade, with a focus on those at tech’s far frontier. That includes startups experimenting at the fringes of biotech, artificial intelligence, nuclear energy, space, and robotics. As Lux itself notes, it specializes in turning “sci-fi into sci-fact.” It has supported players like Variant Bio, Hugging Face, Saildrone, Anduril, Hadrian, Shapeways, DesktopMetal, and many others in that mission.

In addition to his work at Lux, Josh is also a Board Member at the mind-bending Santa Fe Institute – the preferred hangout of one of my favorite authors of all time, Cormac McCarthy; a place once referred to as “the mecca for the science of ‘complex systems.’” He is also a member of the Council on Foreign Relations, a voracious reader of fiction, and the founder of Kurion, a nuclear clean-up company. It played a pivotal role in Japan’s recovery from the Fukushima disaster.

Here are his meditations.

Learn how the best businesses and investors win. Every Sunday, we unpack the business world’s most important innovations and the stories behind them. Join 64,000 others today.

1. What would you be doing if you didn’t work in tech?

Science – perhaps, working at a multidisciplinary lab, studying the intersection of different disciplines. The Santa Fe Institute is the rare place that excels at this sort of work. It brings brilliant, curious, serious, and irreverent practitioners together into a contrarian collective – as oxymoronic as that may sound. Together, they investigate the science of complexity, exploring universal phenomena like power laws and scaling laws. They work to understand things like signals, noise, and emergent phenomena like quorum sensing or non-equilibrium dynamics in financial markets.

What the Santa Fe Institute does so well is leverage analogies from one field to unlock insights in another. This is something I love and can think about endlessly. For example, studying the evolved foraging strategies of ants helped me formulate a worldview of “randomness and optionality.” When ants finally find a morsel of food, they send chemical signals to others in the colony. It’s similar to the work I do as a venture capitalist: scouring for unseen crumbs and staying alert to new signals.

Another example riffs on my unending obsession with the concept of entropy. I am endlessly fascinated by the process by which order emerges from disorder. How can that happen? How does something spontaneously come from nothing?

The work of Nobel laureate Ilya Priogine beautifully explained how dissipative structures (think: whirlpools in a bathtub or a hurricane) share common characteristics. They have observable, stable forms that dynamically evolve in response to unequal distributions of energy or pressure. A similar pattern plays out in finance. Talent, financial resources, and technological know-how often cluster, creating discrete pockets of abundance and scarcity. Companies form to degrade and diffuse these asymmetries, creating new opportunities. Founders might not realize that’s what they’re doing, but from a structural perspective, their work draws on these dynamics to create something like an entrepreneurial hurricane.

2. Which current or historical figure has most impacted your thinking?

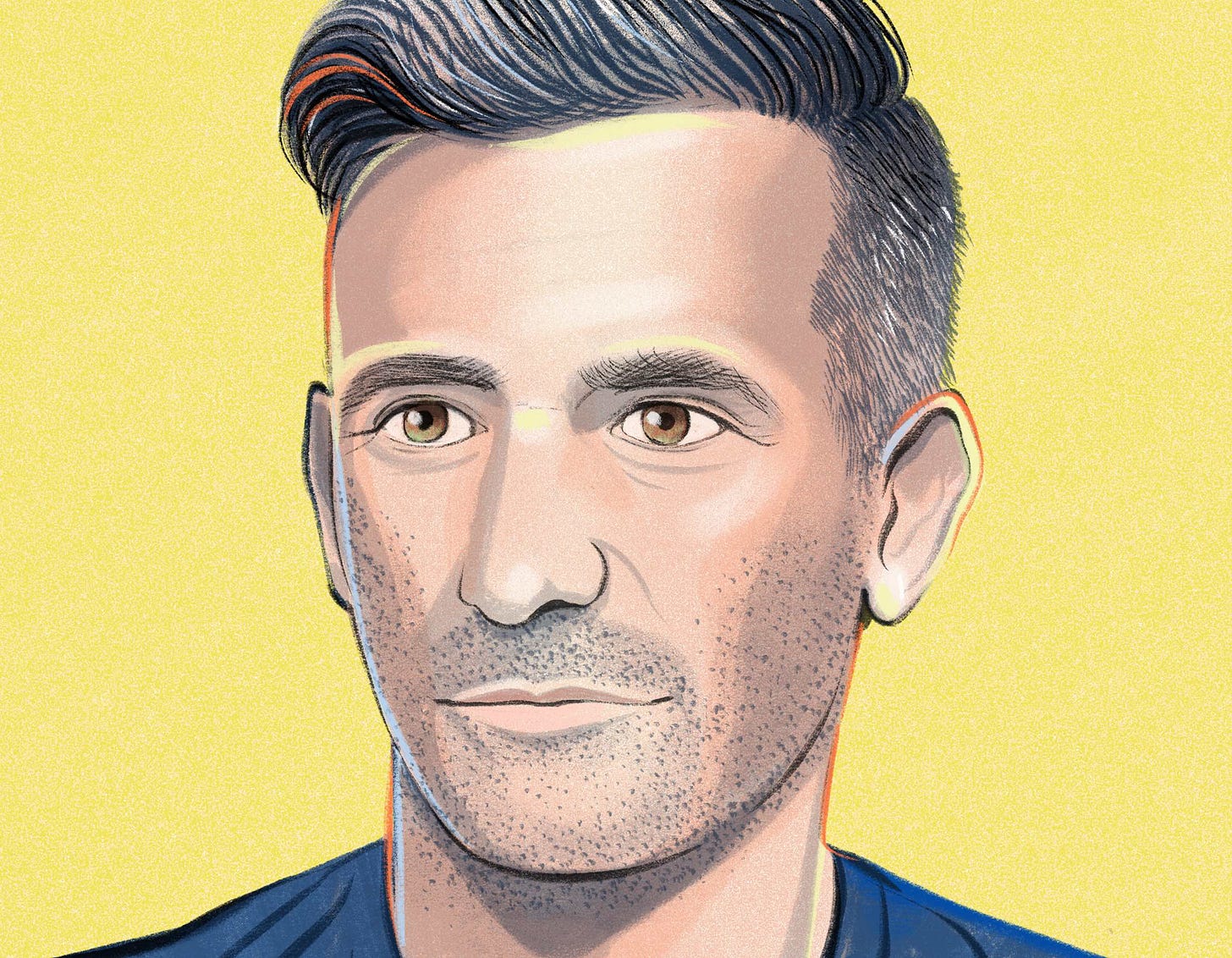

It’s a fight to the death between two nearly-blind polymaths: E.O. Wilson and Charlie Munger.

When I read Wilson’s Consilience twenty-five years ago, it was the first time I realized that disciplines didn’t have to operate in siloes. You can reach into someone else’s domain and find insights and opportunities at the interstices of ideas. Though a biologist, Wilson was a renaissance thinker with a secular, scientific, and erudite prose style. I had never read anything as expansive or eye-opening.

Around the same time, I was given a copy of one of Charlie Munger’s speeches. Immediately, I was hooked. I remember incessantly nodding as I read his thoughts on logic, morality, rationality, history, and humanity. In particular, I was compelled by his invocation of mathematician Carl Jacobi’s dictum: “invert, always invert.” That’s a framing that’s served me well over the years. I think of it as a parent, flipping the experience I had as a child to be a good father.

I also think about it as an investor. It sounds paradoxical, but companies create value by reducing risk. Everyone at Lux is very familiar with the phrase “failure comes from a failure to imagine failure.”

3. What is the most significant thing you’ve changed your mind about over the past decade?

In the past, my wife and I frequently debated how much it mattered who we elected as President. I took a rather cynical position, thinking it made little difference. Our country would pick a politician with a good-looking, symmetrical face and the ability to project power in public speeches. To my mind, that was more or less fine. I trusted the Supreme Court and Congress would temper the worst impulses of any single individual – even one in pursuit of vainglorious self-interest.

The populist debacle that began in 2016 proved how naive I was. Its effects destroyed decorum and decency and created an angsty, antagonist political climate. Critically, this movement also sought to destroy the institutions that exist to check its power. The result of this shift has been profound. The weakest, unluckiest, most marginalized, and disenfranchised people in our society have been subjected to immense pain and suffering.

Another thing I changed my mind about is the power of fiction. I used to read non-fiction – biographies and business histories exclusively. I saw them as case studies, full of lessons about what to do and not to do. Though these books have value, I’ve come to appreciate that fiction reveals more powerful truths. Densely-packed, psychologically-astute prose speaks to the human condition. Though the stage and players may change, our motives, ambitions, petty grievances, and drive to achieve are constant.

One final that I changed my mind about: fruit. I never ate an orange, peach, or pear until I was in my mid-30s. They’re pretty good.

Learn the playbooks of today's global giants. Join 64,000 others to get our next Sunday briefing.

4. What craft are you spending a lifetime honing?

Parenting and photography.

Juxtaposed, the latter trivializes the former. We have three kids: two daughters and a son: 13, 10, and 7. I know reasonably well how to parent each at the age they just were because I lived it, but I never know what comes next. Sure, we use common sense and guiding principles of unconditional love, high expectations, and newer tools we picked up over the years, like validating their emotions even if we don’t agree with what they are doing or feeling. But ultimately, we’re feeling through the fog and searching for stepping stones. We try to avoid catastrophes, lay the groundwork for strong bonds with each other, and make lasting memories.

That’s where photography comes in.

I use a Leica, Canon, or iPhone to take pictures of my family, New York City, street life, and nature. Increasingly, I restrict the number of photos I take to a few carefully chosen black-and-white shots. As much as I enjoy shooting, I especially relish the engineered nostalgia of Google or Apple Photos that remind us of cherished moments. My family used to be annoyed by this habit – “put down the camera already” – but they’ve come to appreciate the memories that get recalled, reshared, and remembered.

5. What is your most contrarian, high-conviction opinion?

That the “environmental” movement is the greatest threat to the environment––unwittingly anti-environmental and opposed to human progress. The loudest voices in this movement are mostly anti-progress and anti-markets, antagonistic to commercial activity, wealth, and human flourishing. They’re almost religious in their adherence to a self-flagellating dogma of austerity or de-growth and too often ignore nuclear energy (or, as I have tried to rebrand it, “elemental energy.”)

Over the past decade, this seems to be changing. There are encouraging signs of reformed or awakened “environmentalists” like Patrick Moore, Stewart Brand, and others seeing the light on “elemental energy,” and directing others to its potential.

6. What piece of art can you not stop thinking about?

I love the crazy complexity and pop surrealism of Robert Williams. As well as the paintings themselves, I love Williams’ triplet titles that range from sophisticated to totally low-brow.

I’ve never appreciated Rothko, Mondrian, or other artists celebrated widely. Some have found transcendence in staring at Rothko, but I find it contrived, conceited, and socially constructed.

I like art that evokes this feeling: whoa! I like seeing the fruits of a complicated, possibly insane mind; a psyche loaded with formative experiences, inputs, exposures, and memories. You see that with Williams and, of course, with someone like Hieronymous Bosch. Stare at a Bosch triptych, and you see the lunacy from his perspective.

I also love kinetic sculptures and magic tricks. Both are highly engineered art that compresses an enormous amount of planning, intelligence, and cleverness into a final display.

7. What are you obsessed with that others rarely talk about?

Entropy and life’s fight against it as a universal phenomenon.

Also, the philosophy and science of magic. I’m fascinated by the unwilling suspension of disbelief and the ability great engineers, conjurers, and masters of legerdemain have to attract, misdirect, surprise, and awe.

From an investment perspective, I’m mostly obsessed with three domains at the moment: inner space (biology), outer space (aerospace and defense), and latent space (the infinite possibility emerging from generative AI models).

8. What contemporary practice will our descendants judge us for most?

The inhumanity of incarceration. We are destroying (mostly young men’s) lives and family structures and perpetuating a cycle of poverty. Our current system primarily solves for victim catharsis, retribution, and justice. We don’t do enough to deter crime at a more fundamental level. From a young age, citizens should have access to resources that teach emotional control, especially over our most primal impulses. We also need to address systemic inequalities in education and economic opportunity.

Though it might sound like a petty quip, the power and suppression that resides in religious authority are related to this problem. Around the world, from theocratic Iran to democratic America, religious groups encourage tribalism and dogmatism. While these groups may also engage in humanitarian or philanthropic activities, their aggregate impact is divisive and detrimental.

9. What risk are we radically underestimating as a species?

Low probability, high magnitude risks are well-trodden. They appear in our imagination, fiction, and legislation. Infectious disease, bioterror, nuclear war, malevolent AI, and environmental collapse are frequently discussed and, in some instances, part of our current reality.

All are worth paying attention to. In the name of efficiency, though, I would highlight our dependence on any number of tightly coupled systems. That includes technological interconnectedness, information storage, and our electrical grind. Without sufficient redundancies, the failure of one node in these systems can ripple out and create real damage.

Another risk that feels more imminent (and probable, in my view) is a geopolitical conflict on the African continent. In particular, one involving China and Russia. China has used infrastructure projects and debt diplomacy to establish a level of control through its Belt and Road initiative. Meanwhile, Russian-owned mercenary organizations like the Wagner Group sew chaos and receive concessions from Africa’s extractive industries, such as precious metal mining.

The inflow of extremists from Afghanistan, Syria, and Iraq to the Sahel and Maghreb further increases the potential for violence. One possibility is that terrorist activity from these groups prompts African countries – particularly former colonies – to call for support from Europe. Retaliatory action from European countries could turn the region into a tragic repeat of Afghanistan.

10. If you had the power to assign a book to everyone on earth to read and understand, which book would you choose?

If I had to narrow it down to one, I’d pick The Beginning of Infinity by David Deutsch.

If you allow me a few others, I’d add The Origin of Wealth by Eric Beinhocker, Complexity by Mitchell Waldrop, How the Mind Works by Steven Pinker, and, of course, Consilience by E.O. Wilson.

11. How will future historians describe our current era?

As better than prior eras that came and worse than those to come. I am a conditional optimist (distinct from a complacent one) and view our species as fallible but motivated by self-interest to find and fix problems. In pursuit of status or some collective interest, we reliably uncover what sucks about our current existence and devise solutions.

On a relative basis, our world is getting less violent, more connected, and more cooperative – even if there are spurts of isolationism, nationalism, and retrenchment. Those reactions come from fear of change or fear of “others” gaining power in what some see as a zero-sum game.

Our increasing connectedness does heighten some risks. As we all know too well, it can accelerate the spread of infectious diseases, for example. By and large, though, it benefits us, creating the conditions for unprecedented cooperation and ingenuity, as the discovery and distribution of vaccines showed. Ultimately, I’m in the Martin Luther King and Steven Pinker camp; I believe the arc of the moral universe is long but bends towards justice.

The Generalist’s work is provided for informational purposes only and should not be construed as legal, business, investment, or tax advice. You should always do your own research and consult advisors on these subjects. Our work may feature entities in which Generalist Capital, LLC or the author has invested.