Writing is usually seen as a solitary pursuit. The author or journalist is typically depicted as a lonely figure bludgeoning away at a blank page in hermetic seclusion.

The reality is more nuanced, of course. Even the artists we think of as singular geniuses were, in some sense, collaborators, entering into productive communion with others. Vladimir Nabokov relied on his wife Véra for translation and first impressions; an elder James Joyce, eyesight failing, relied on the help of a young Samuel Beckett to finish Finnegans Wake.

What might sound anecdotal is, in fact, commonplace. From researchers to editors, translators to publicists, writing in the public domain has always relied on multiple parties. Even in seducing the reader, a kind of consensual collaboration forms.

And yet no one would confuse the focal point of such works. Though they may be flanked by lieutenants, the writer, the author, is unmistakably the point of the spear. The boxer may have his brow wiped by a manager and train with a coach, but only he can walk into the ring and get punched in the mouth. Writing is authorial, in the etymological sense, originated by one person.

This may be changing. As new economic structures and orchestration systems develop, writing may take on a different shape, one that unfetters the adjuncts that have typically remained in orbit and bring others to the task.

The end result will look less like a lonely pursuit, subtly aided by others, and more like a shared game, with each participant bringing their own skills to bear and profiting on the upside. The same opening and decentralizing powers that visit writing may appear in other artistic endeavors. In time, this shift may formalize as an entirely new model for creation and communication, best described as multiplayer media.

In today's treatise, we'll fumble (and hopefully find our way through) the following:

The path from monolithic to multiplayer media

Necessary creator logistics to sustain the movement

The Generalist as a multiplayer media company

Monolithic to multiplayer

On a list of exciting ways to begin a theorem, a caveat must surely rank near the bottom. While I am tempted to bluff, ornamenting the weaknesses of argumentation with a poetic flourish here and there, I know this readership is too astute to fall for that. (If I can't interest you in a flourish, may I offer you some flattery?)

So, a divulgence: I believe in the coherence of this next section and find it to be true. But there are convolutions and exceptions at which a reader might reasonably point or poke. I hope you will — if this piece had one overriding wish, it would be to break the wall between "audience" and "creator" as frequently as possible.

Monolithic

The first complication: despite what I noted in the introduction, traditional creativity has — in relative terms — been monolithic. On a spectrum of collaboration, though not solitary, classical novels have been comparatively individual.

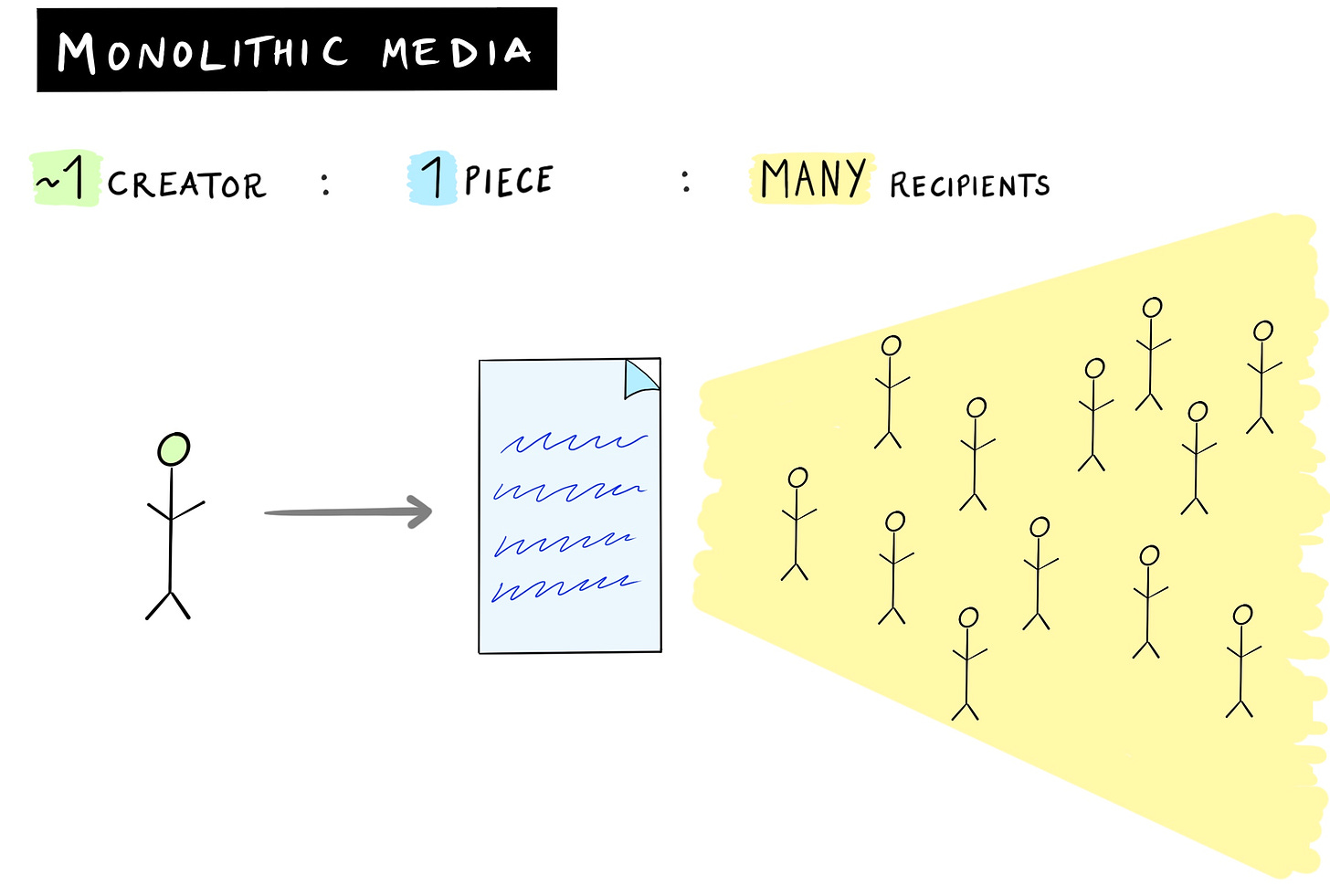

This paradigm can be reasonably referred to as monolithic media, and it is an apt descriptor for the model of creation to which we are most used. Though participants are involved either pre or post-opus, the burden for creativity tends to rest on a single individual. The final product is disseminated to many people.

Let’s continue with the example of a novelist.

A muse may influence the pre-opus process, and an editor may sharpen post-opus. But it is up to the writer to fabricate the story in all its richness. The same outline holds for the creation of more commonplace written works, like a news article. Researchers may help beforehand, fact-checkers may lend a hand after, but the creator is solitary.

Even in cases in which there are dual-creators (or more), the rough ratios hold. One (or a small number) of creators create one piece to be distributed to many.

The power in this model lies with the distributors. Only those that had access to distribution power could have their work seen. It didn't matter whether you were the best journalist in the world — without a paper, no one could read your work.

Manic

The internet changed this dynamic entirely, with social networks playing a crucial role. While brand power translated into online distribution power in some cases, the totality of control was attenuated. Sure, you're likely to have more readers if you write a piece for The New York Times, but your random Medium post may outstrip it. At the very least, others are more likely to see your work.

In loosening the grip on gatekeepers' distribution power, a new model of manic media emerged. A few vital shifts characterize this epoch:

An exponential increase in output

The fracturing of the opus

The emergence of "chaotic collaborations"

Each is meaningful. Let's work through them.

By providing the platform to find an audience, social media allowed everyone to be a creator. You no longer need permission to share your thoughts with the world.

What was non-obvious was that (almost) everyone wanted to be a creator of some kind or another. A labor surplus was revealed, a creative surplus, that showed that even those with arduous jobs and serious responsibilities would make time for tasks that might feel like work in a different context. Writing a story under the auspices of a newspaper feels like work; writing one on Twitter feels like fun. This resulted in a step-change increase in output that we are still grappling with. Whereas fifty years ago, the average citizen might have read the morning paper, written by the same fifty writers, today, we dance from one platform to another skimming hundreds, thousands, of perspectives in miniature.

Compared to monolithic media, this aspect of manic media gives it a very different shape. Typically, it involves many users, creating many pieces for an enormous audience; a ratio of many to many to many.

This alludes to the second shift: the fracturing of the opus. The successful social media platforms constrained means of expression, either overtly or implicitly. Twitter restricts the storyteller to 280 characters; Facebook rewards short, high-emotion commentary; Instagram, Snap, and TikTok prioritize brief clips.

Creators adapted by splitting what might have once been one cohesive piece into dozens of micro-stories. In doing so, storytellers opened the door for others to interact with their content piecemeal, effectively line by line or frame by frame. We're used to this now, but it represented a seismic adjustment of the boundaries between artist and audience. Whereas in the past, you might have written a letter to the editor to cavil with a particular argument, now spectators can react in real-time, signaling approbation or condemnation.

Stand-up comedy often feels like the most Pavlovian of art forms; the dog is the performer. Comedians hone their set, navigating by the sound of the audience’s laughter. The jokes that work are embroidered upon, extended, repositioned, while those that don't are jettisoned. The art changes and improves with the help of the audience.

This same dynamic guides much of online creativity now. The Twitterer that sees a thread about bitcoin go viral may lean in to post almost exclusively about crypto-currency; the TikToker that pops off by making a single funny expression (think Khaby Lame) will find ways to resurface it again and again. Art is developed both with and for an audience.

(This principle can be boiled down to the general advice: lean into your winners. This is something both money-men and retailers speak about. Both public and private investors frequently counsel doubling-down on winning bets, while it is accepted wisdom among consumer businesses that you should usually lead with your most popular offering rather than your newest. If your best-selling item is a little black dress, put that in your storefront window.)

This shift changes the texture of the creation. Classic Greek tragedies often employed a "chorus." This cohort commented on the play's action, highlighting major themes, filigreeing a character's emotion, and enriching the piece's fabric. Social media platforms give modern creations the same dynamic, serving as a modern chorus: every fragment of an opus is accompanied by a layer of critique. The audience can not only participate, but the art it sees is contextual, striated.

The difference between the ancient and modern "chorus," of course, is one of control. The original chorus was a narrative device, defined and contrived by the author. It was not a collaboration, so to speak, so much as the appearance of one. The modern chorus is very different; it is a collaboration, but an entirely chaotic one. The creator holds little to no control over the direction or degree of cooperation.

These "chaotic collaborations" are a defining feature of social media and can lead to genuinely memorable creations.

In 2019, for example, user @Fred_Delicious asked his Twitter followers for the "most ridiculous name[s]" they'd come across:

The responses are fantastic. There are the two brothers, "Timothy" and "Dimothy"; "Charity Hamjack" the call-center worker; "Dijon Outlaw" a youth wrestler; and one "Dr. Barney Softness."

Whether you consider this thread and others like it art is a matter of perspective and context. But the output functions similarly to an open-mic comedy night: someone appears on stage, makes you laugh, and then yields the floor to the next performer. This is a chaotic, spontaneous collaboration that succeeds as a piece.

A more direct example might be something like the "Zola Thread." The 148-tweet storm from Aziah "Zola" Wells is a twisty-turn tale that has since been adapted into a film from Academy favorite A24. Since the original thread has been deleted from Twitter, it's difficult to ascertain to what extent the piece was collaborative. Still, the version that exists on Genius's archive suggests responsiveness to audience commentary.

TikTok appears particularly geared for this kind of creativity both implicitly and explicitly. Memes — often through dance or music — spread rapidly, contributing to a sort of large-scale "suprawork." "Duets," in which a clip is positioned side by side with a successor, invite participation and reinterpretation of the initial work.

While these examples show the promise of mass participation and narrowing the divide between creator and audience, they are rarities.

By and large, chaotic collaborations result in incoherence. Though social media platforms provide some guidance, there are many ways to play the "game" and few rules. If I posted a tweet asking users to create a story, one tweet at a time, what would happen?

It's possible that something great would come of it, but unlikely. Without clearer guide rails, different degrees of permissioning, and perhaps some reward system, the likeliest outcome is an anarchic, senseless mess.

Why is that? Because everyone is playing a different game.

Each social platform is capacious enough to allow for a multitude of interpretations and styles of play. On Twitter, for example, some people are playing the "thread game," others play the "meme game," others play the "snark game." Each of these may have value within the context of the social network. But when committed to a collaboration without orchestration, they typically erode rather than contribute to the piece's value. (Often, this leads to mutual frustration as each participant blames the other for ruining their version of the game as if someone started playing hockey on your tennis court, or visa-versa.) The creative surplus described above is not quite wasted, but it certainly isn't optimized.

Viewed in totality, the manic media era enabled vital new behaviors, allowing many more people to create, forcing communion between artist and audience, and permitting chaotic collaborations. It falls short in many places, too. By focusing on fractal pieces and empowering a range of different games, the scale and coherence of collaborations have been capped. The next wave of media will take the best of this previous era but empower grander and more sophisticated play.

Multiplayer

Unless you are a rather strict adherent, you will agree with me that one of society's most consequential pieces of media was multiplayer.

Most academics believe the Bible was written by dozens of authors, with many others potentially contributing in some fashion or another. Rather than an anomaly, we may come to see such collaborative creations as the norm.

"Multiplayer media” represents the next frontier for creativity and collaboration. The greatest novel of the next century, the most immaculate film or game, will be architected by vast, opt-in networks. Rather than involving a few dozen contributors, thousands will participate, creating something closer to an artistic MMPORG rather than a humble guild.

As with manic media, participants will be widely distributed and enter conversation online. The distance between artist and audience will not just narrow but entirely collapse as viewers become creators.

This will be managed by aligning users around a specific game rather than a platform that allows multiple non-consensual games. By doing so, creative surplus is better directed, with "coherent collaborations" taking the place of chaotic ones. Sophisticated permissioning and reward systems (not necessarily via DAOs) match and compensate participants appropriately. In that respect, creative endeavors may be structured similarly to open-source software projects.

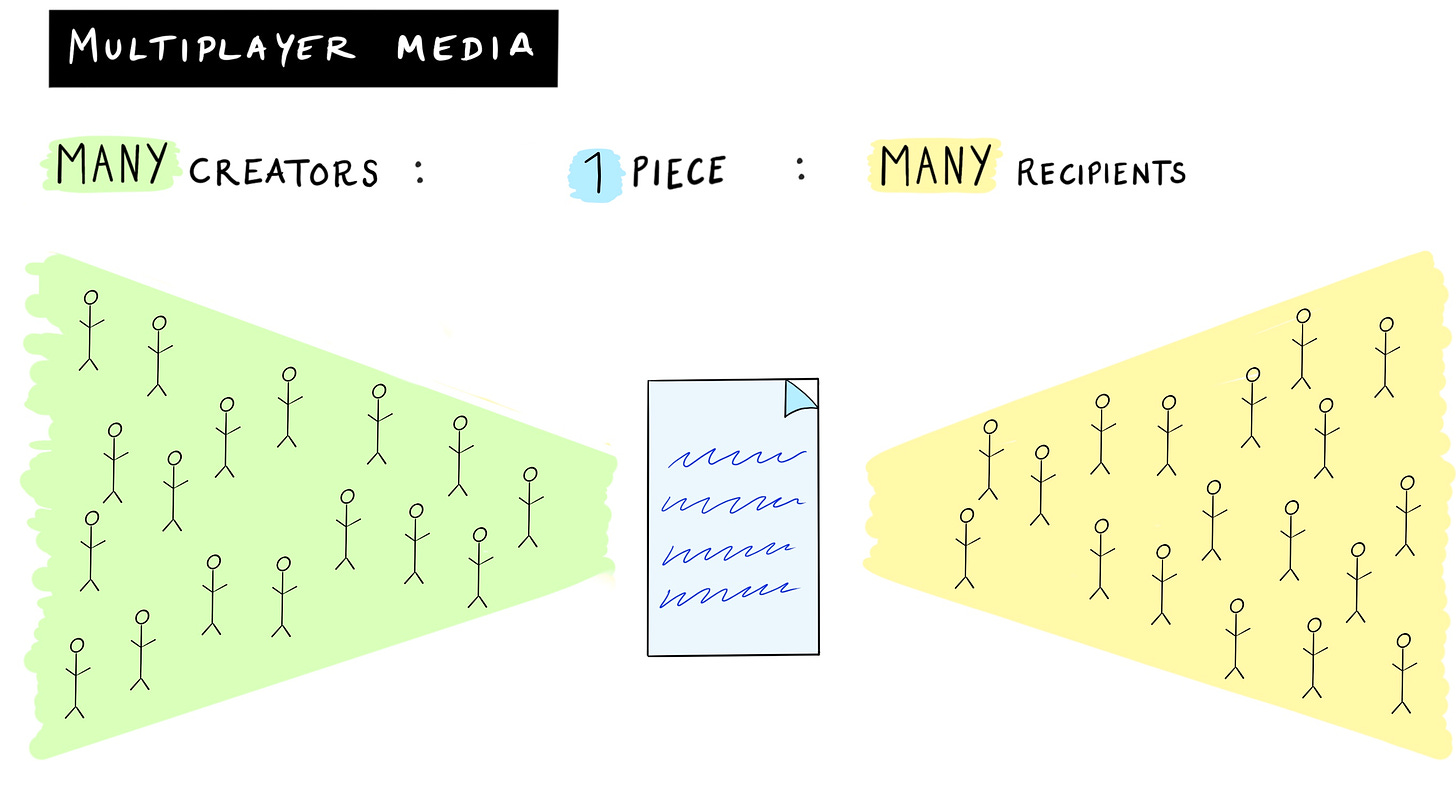

The shape of creation is once again shifted. Within a multiplayer framework, many people work on one piece, viewed by many.

There are clear benefits to this system when compared to both monolithic and manic media.

First, by harnessing creative surplus, multiplayer media projects benefit from free or lower-cost labor at scale (think Wikipedia).

Second, by shifting creation downward toward the audience, multiplayer pieces effectively become headless. Unlike traditional media (or even social media), headless art is more resilient to censure — whereas the painter Gauguin might have been canceled in the modern era (three child brides? Really Paul?), curbing his production, a multiplayer rendition of the same art would be less vulnerable to individual foibles.

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, multiplayer media offers viral distribution. By involving many more participants, multiplayer art simultaneously mints many more evangelists. Those that work on a product and bring it to completion are likely to want to share the output, particularly if their fortune is in some way tethered to the project's success (think Bitcoin). If attention is a war, it does not hurt to have one's own army.

While there are signs this movement is already emerging, empowering more mass-scale projects requires a logistics of creativity.

Creator logistics

To bring 10-10,000x the number of collaborators into a project, creative fields will need to perceive and formalize work as a coherent process. That will involve mapping its steps, defining roles, choosing and distributing rewards, and employing "synthetic creators."

Mapping the supply chain

Though artistic output is often portrayed as flighty and ineffable, creativity has a supply chain. To permit collaboration to occur on a much larger scale, creators will need to define their processes explicitly so others may tap into them.

Though there is undoubtedly considerable variation from medium to medium and artist to artist, a rough loop might involve the following stages.

Priming. Before a precise idea strikes, a creator processes information from different sources. Though the relationship is not linear, these sources ideally encourage cogitation and lead to the next stage.

Inspiration. The creator alights on a specific idea they believe to be worth exploring further.

Research. To formalize their approach, the creator researches related works, new techniques, or other relevant subjects.

Structuring. Once a state of play has been ascertained, the creator outlines their approach.

Drafting. Using the skeleton from the prior phase, the creator fabricates the first version of the work.

Refinement. After reviewing the work completed in the prior stage, the creator refines the piece, perhaps over multiple cycles.

Publication. Once the creator is satisfied (or believes they can do no more with it) the piece is published and shared with an audience.

Feedback. The audience responds to the piece influencing the artist's subsequent work. (Even if a creator chooses to ignore the audience, that decision is made within the context of an audience existing; you cannot “show the haters” in a vacuum.)

Forking. Though not always the case, the initial publish piece may be "forked" by other creators. A recognizable example is fan fiction which takes the world of an existing work (think Harry Potter) and spins a new story. Translation is another. Though we don't always think of them this way, less formal examples include distilling primary lessons in a tweet thread, writing a formal response as a published piece, using the source material as a podcast topic, and many other iterations.

Up to the moment of publication, this is a comparatively solitary pursuit (again, with the caveats discussed earlier). What would it look like to open this supply chain and enable multiplayer functionality?

Once a clear objective is set (writing a mystery novel, for example), almost every phase of the process could be productively radically reimagined as a team sport. Participants could surface and upvote the most chilling, intriguing content (priming); contributors could suggest a central conceit for the plot (inspiration); analysts could dig into arcane or specialist subjects — perhaps entomology, toxicology, or blood splatter patterns given the topic — enriching the plot (research); experienced storytellers could contrive a suitably surprising story (structuring); wordsmiths could write various sections under shared stylistic guidelines (drafting); and editors could look for inconsistencies and suggest improvements (refinement).

Publication might look similar, but distribution wouldn't — thousands would proselytize the project upon launch. Data analysts could collect and parse reader responses with greater nuance (feedback), perhaps better informing where the collective should move next. Finally, a superabundance of video editors, podcasters, linguists, and enthusiasts could remix the product (forking), bringing it to new markets and new mediums.

While each of these steps sounds feasible in the abstract, such coordination is near impossible today. How would you attract people to your product? Where would you share resources? Who would play what role? How could you deliver the right instructions to the right person at the right time? How would you align around timelines and expectations?

To bring projects like the one described above to fruition, new infrastructure is needed that borrows from open-source software communities and beyond. You can imagine a range of tools, including recruitment and application management, process mining to identify new discrete stages in the creative process, and sophisticated forking tools.

Roles and permissioning

Open-source software communities typically adhere to a specific anatomy.

The author creates the project; the owner administrates the project (it may be a different person from the author); maintainers oversee certain parts of the project; contributors add to the project in various fashions; and community members use and comment on the project.

Similar hierarchies are necessary for creative pursuits. At the moment, Google Docs offers just three "roles": Viewer, Commentor, and Editor. This makes sense for collaborations below ten active participants; beyond that point, chaos reigns. Comments become hard to track, corrections overlap, versioning bewilders.

This is not a failure of Google's but rather a reflection of the type of creative processes it is suited for. Reimagining something as simple as a word processor for a multiplayer use-case hints at how multiplayer projects could flourish with better permissioning and definition. (It may also be a big opportunity for the right founder.)

What would it mean to have sub-organizations and hierarchies within a doc? How can you grant one group access over some passages but not others? Whose comments should be given particular weight? How do we contextualize one person's suggestion when we don't know them — through badges? Points? How can different proposals for the same problem be ranked and compared — can we fork different storylines and play them out to see which works best? How do we record, beat by beat, which lines 10,000 readers enjoyed? Which they hated? Could we have tiny emojis sit over specific passages just as they appear at the bottom of an Instagram post or Loom video?

The opportunities are endless here, and each element of the creative process could be passed through this filter.

Reward structures

It's remarkable that arguably the two most successful online multiplayer creations of the last twenty years relied on unpaid workers. Both Wikipedia and Bitcoin have scaled to absurd sizes on volunteers' backs, inspired to work without tangible reward. Many successful open source software projects have done the same.

These occurrences are proof of the labor surplus described previously — if work is sufficiently fun, we will do it for free. For nine years before I started The Generalist, I woke up an hour or two early and wrote. For many people, this would have constituted work — for me, it was pleasure.

Multiplayer media can tap into that potential, scaling projects without significant increases in opex. By providing opportunities for self-expression, connection, learning, and career advancement, multiplayer projects can attract meaningful, high-caliber free labor. Just as it is the case in software development, playing a role in creating a significant multiplayer piece should grant users status (at least within some topical locality) and demonstrate a skill set useful in recruiting for new positions.

But money is nice, too.

Multiplayer contributors can and should be rewarded through traditional and insurgent currencies. DAOs — Decentralized Autonomous Organizations — illuminate one pathway. By issuing a community token, a multiplayer organization could reward collaborators for their specific contributions. As the value of the community's work increases, token value increases, and collaborators prosper. Should sophisticated splitting and payments come to the creator economy — think Stir's "Splits" functionality on steroids or a tweaked Stripe Connect — equivalent payouts should be possible with fiat.

Returning to the mystery story mentioned above, you can imagine each collaborator being compensated according to the extent, impact, and difficulty of their contribution, earning a percentage of the upside from book purchases or the sale of film rights. In time, multiplayer media projects will sustain opt-in contributors at and beyond the levels of traditional employment.

Ghosts

If the Greek chorus served to react to the primary storyline of a theatrical production — augmenting the audience's understanding — ghosts often reveal something new to the players themselves. Hamlet’s father reveals his killer to his son, spectral Banquo is trailed by descendants, alluding to the shortness of Macbeth’s reign, and Ebenezer Scrooge is shown the error of his miserly ways by the ghosts of Christmas. (Ok, this last one began as a novella. But you get the point.)

Multiplayer media may require similar immaterial visitors in the form of AI. It is almost certainly impossible for a single individual, or even a dedicated team, to stay on top of the creative contributions of a large group. Destructive shifts in style or characterization could easily go unseen for long periods.

To protect against missteps like this, multiplayer projects may employ "synthetic creators" that rely on technologies like GPT-3 to sniff out inconsistencies and fill in the gaps.

You can imagine a future in which one team of writers constructs "Part 1" of a novel while a second group writes "Part 2." Knitting those two sections together could be done manually but would be time-consuming and tricky, likely requiring multiple passes. A synthetic creator could seamlessly ingest both parts, pull out the primary storylines, and provide a selection of narrative bridges from which the community could choose. In the struggle to smooth thousands of different voices, AI systems may sand and polish ungainly joins and scraggly edges.

In sum, multiplayer media can create extraordinary tangible and social capital, bringing together disparate groups in pursuit of a single creative endeavor. New technologies, sophisticated reward systems, and even technological ghosts may be necessary for true scale.

The Generalist: a Multiplayer Media Company

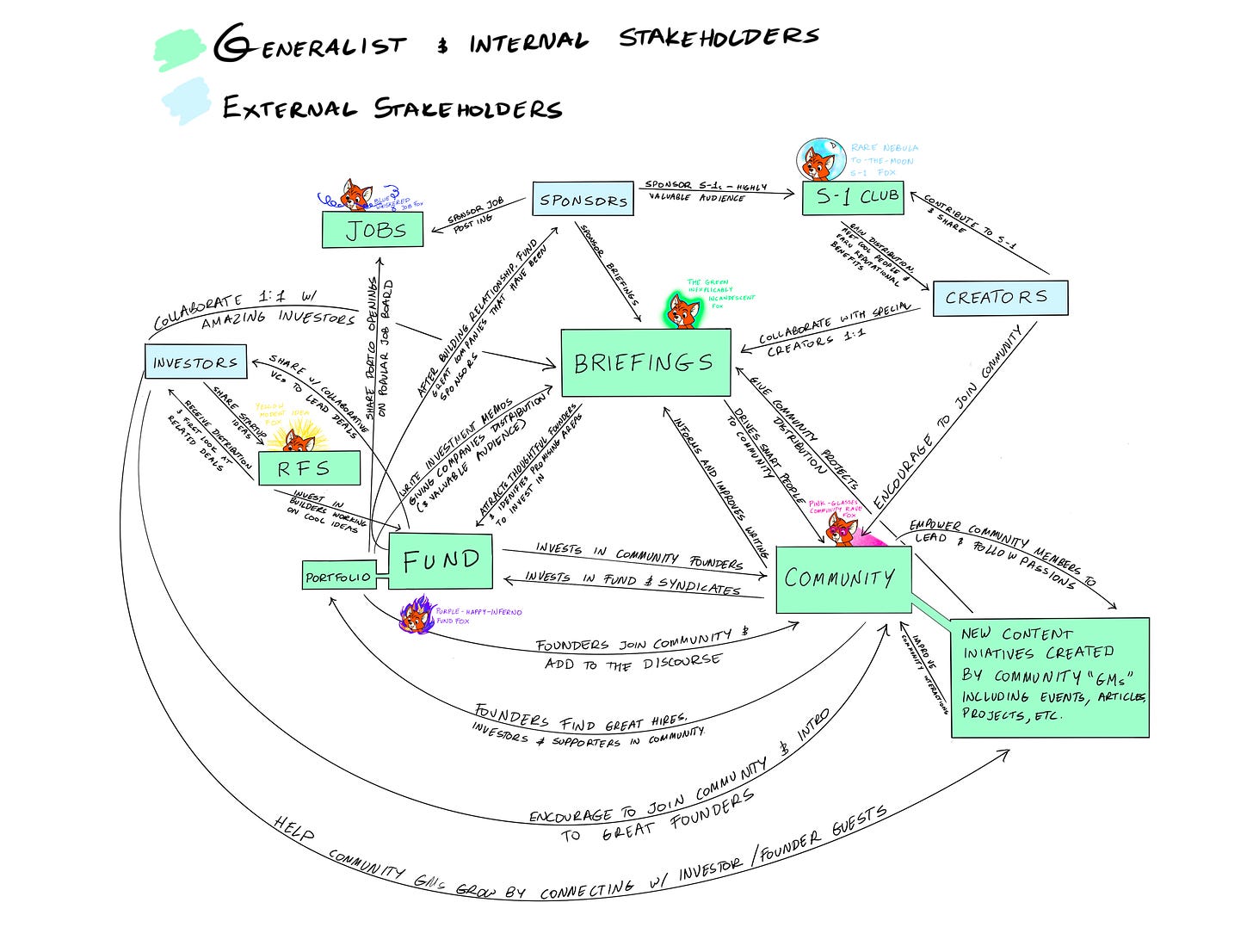

Over the past week, I have been thinking a great deal about the future of The Generalist. Sparked by some conversations with community members, I drew the diagram below — my rendition of the iconic original Walt Disney composed.

Though alluded to, something fundamental to the project is missing — namely, that The Generalist is a multiplayer media company.

What I am striving to construct is not a newsletter that shares one person's ideas or research, but a platform and community that gives some of the smartest people in the world ways to learn, connect, collaborate, and prosper. In doing so, I think we can create some of the best media — the sharpest and most creative reports and pieces — in the process.

This mission is still in its infancy, but I think you can see the early indices. The clearest instantiation is The S-1 Club.

Rather than having a single analyst break down a company heading to the public markets, we assemble a group of experts particularly chosen. That involves contributors of differing expertise, seniority, and skillsets. Some bring a public equity mindset to the team; other's a VC approach. Some specialize in forensic financial analysis; others have a keen product sensibility.

The result is a multiplayer product that is readable as a cohesive whole but (I believe) has a richness and depth that would be difficult for a single person to achieve. It benefits from most of the advantages mentioned previously, including improved distribution and low opex. No contributor is salaried. Instead, some of the most impressive investors and founders in the tech world have joined because it is fun. Learning, collaborating with other intelligent people, provides a non-monetary reward.

(An intriguing aspect to this kind of production: many, if not all of the contributors to The S-1 Club, are not only not hired but could not be hired. Doing so would turn the game into a job, and experienced, impressive people are not typically looking for contracting jobs.)

In one particular S-1 Club (Coinbase), contributors received part of the financial upside via NFT sales, indicating how The Generalist might permanently implement a financially aligned strategy.

Though I would still consider The S-1 Club multiplayer media, it sits at the minor end of the spectrum. The number of contributors tops out at about 10. While that has proven a manageable size, it's enticing to envision a version with 100 or 1,000 contributors.

How could we wrangle that?

Would we want to involve a cohort of 40 "researchers," adding to the story and smoothing the creative process? How about 30 "proofreaders" sniffing out typos and other errors? Should there be a cohort of 10 graphic designers illustrating key points? Perhaps a trio of podcasters adapting the output for audio?

With the proper infrastructure and rewards, and sufficient bandwidth, many iterations and forks are possible.

This framework could be applied to other types of content, too.

Why couldn't every weekly briefing showcase dozens of brilliant people, collaborating to manifest a story that not only entertains but informs?

And why can't there be more of the same? I have enjoyed digging into Latin American companies like Mercado Libre and Nubank. What would it mean to have a "multiplayer collective" creating pieces on the continent's most remarkable business stories each month without my express involvement? What about expanding that initiative to every geography?

As time goes on, I hope to increasingly develop The Generalist into a purveyor of headless art.

Already, the private community is indicating the merit of that approach. Many of the most interesting anecdotes, cleverest ideas, and best suggestions come through conversations on the platform; the creative supply chain is open and has improved dramatically for it. As I look ahead, I hope and believe there will be many more opportunities to direct the creative surplus in that cadre towards coherent collaborations that result in meaningful outcomes for each contributor.

Though self-assured and prone to solipsism, even Nabokov recognized the beauty of communal creation, on the grandest of scales:

“Existence is a series of footnotes to a vast, obscure, unfinished masterpiece.”

To be alive at all is an act of wild, imbricated interdependence, of evershifting, ever-bewitching connection. Is it so strange that we should wish our writing, our art, to resemble its shape?

We are halfway there. Though social media revealed everyone to be fundamentally creative and brought people into communion, it did so chaotically, destructively, largely frittering the surpluses of labor it unearthed. The next phase of creativity will build on its successes and address its failures, aided by new infrastructure and nuanced underlying governance and reward mechanisms.

At its incandescent edges, multiplayer media promises something close to the Nabokovian metaphor for existence: a method to work and play together on something great, beautiful, and larger than ourselves.

The Generalist’s work is provided for informational purposes only and should not be construed as legal, business, investment, or tax advice. You should always do your own research and consult advisors on these subjects. Our work may feature entities in which Generalist Capital, LLC or the author has invested.