Nadia Asparouhova on antimemetics, nuclear mysticism, and scrolling

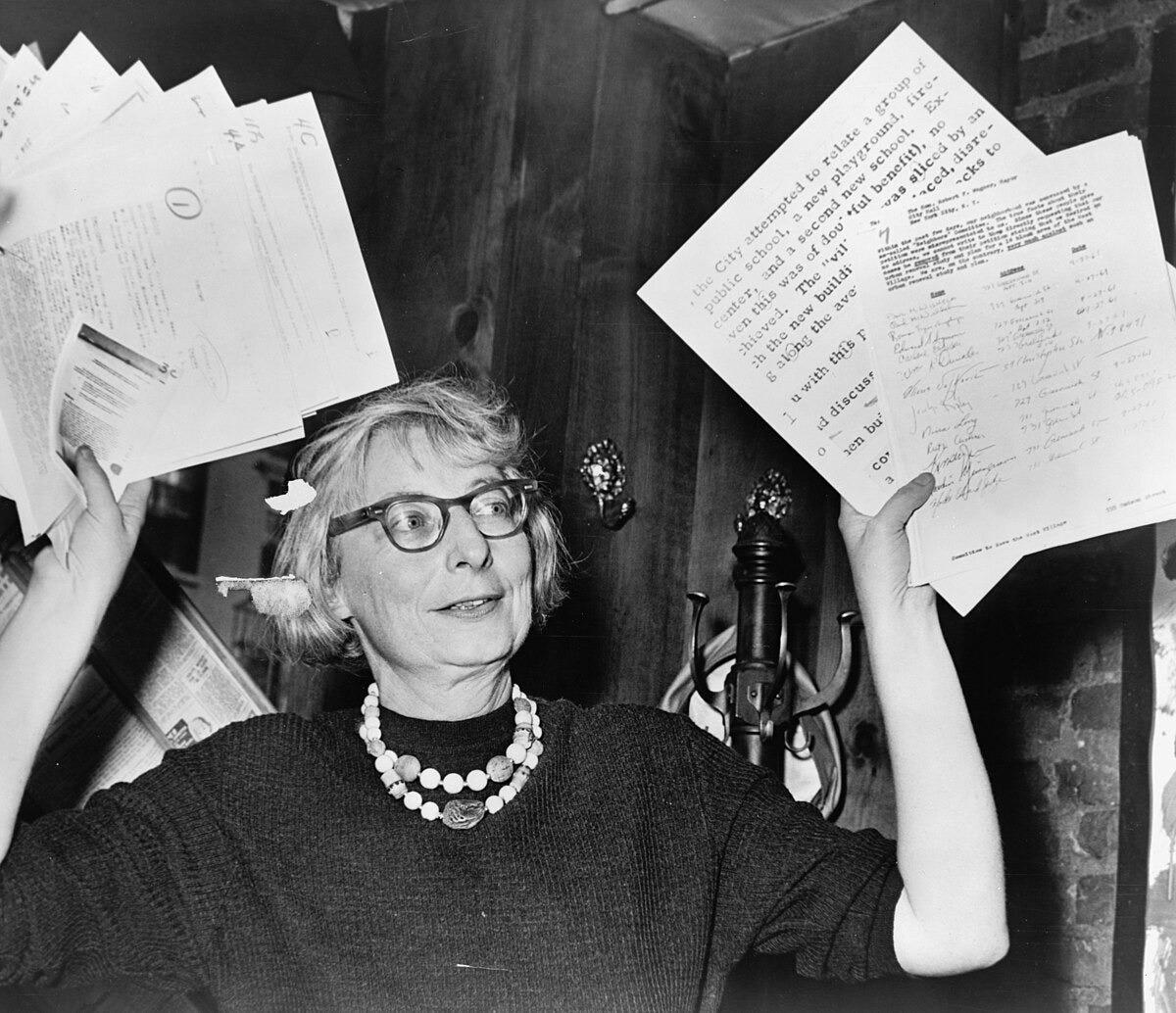

The independent researcher and author of “Working in Public” shares her thoughts on “gentlemen scientists,” career games, and Jane Jacobs.

“Mario is incredibly thoughtful and diligent in the craft of writing about technology. One of the real ones!” — NBT, a paying subscriber

Friends,

Some people appear to be born with uncommon wisdom. Nadia Asparaouhova is, seemingly, one of them. For some time, I have enjoyed reading her thoughtful writing on open-source software, the dynamics of the modern internet, the inherent trade-offs of protocols, and the compelling mysteries held by advanced meditation.

(If you haven’t read her work before, I highly recommend Nadia’s Substack Monomythical and her book Working in Public, published by Stripe Press.)

She reads our current technological landscape unusually, clearly, and with an appreciation for its impact on our society and minds. For these reasons, I was especially excited to hear Nadia’s thoughts on the off-piste questions at the heart of the “Modern Meditations” interview series.

Below, you’ll find Nadia’s thoughts on the chaos and beauty of our era, the damage of being a permanently distracted species, re-engaging with religion, and enjoying the email inbox.

Nadia is publishing a new book on antimemetics exploring why some ideas spread slowly or not at all – which is one of the most interesting premises for a book I’ve heard in some time. It’s coming out soon and I suggest you keep an eye out for it on her website.

To unlock The Generalist’s full archive of interviews, case studies, and tactical guides, consider becoming a premium subscriber today. For $22/month, you’ll discover breakthrough startups, hear from investing legends like Vinod Khosla, and access the playbooks of elite founders.

Modern Meditations: Nadia Asparouhova

What are you obsessed with that others rarely talk about?

I’ve been going deep on antimemetics – or why some ideas spread slowly, or don’t spread at all. It feels like after we got social media, we came up with a bunch of principles around “virality” and “memes” and then never revisited them again.

But ideas don’t spread the same way they did in the early days of Web 2.0. Now, we sometimes deliberately keep our spiciest thoughts and compelling ideas under wraps, because we don’t want them to spread too fast, or to the wrong people. We shield them from the harsh dynamics of the public web, saving them for group chats. I think this is under-discussed, so I spent the better part of this past year exploring these dynamics in a book about antimemetics that’s coming out soon.

Which current or historical figure has most impacted your thinking?

I’m drawn to figures like Elinor Ostrom, Jane Jacobs, and Ina May Gaskin, who made their names by adopting a healthy skepticism of conventional wisdom, looking at the world around them, and writing down what they saw.

There’s so much in the everyday that gets overlooked by people jostling to construct the biggest, most impressive-sounding theories, which are totally divorced from reality. But I think that even the very small can yield infinite possibilities. You could draw a square inch around anything and discover something novel and interesting about whatever lies within. That’s how I’ve approached my work and interests: always trying to keep my eyes and ears open for the unseen ideas that are hiding in plain sight. So far, I’ve been amazed by how fertile the world is, and how much more there still is to discover.

What tradition or practice from another culture or era do you think we should widely adopt?

I wish patronage were widely adopted as an explicit social norm. So-called “gentleman scientists” and patron-funded scientists, such as Charles Darwin and Isaac Newton, were behind some of the biggest scientific advancements in the 17th through 19th centuries. I think we got a little confused with the introduction of crowdfunding in the early social media days, which – while certainly a viable funding path – isn’t really the same thing. With time and scale, crowdfunding can feel more like pandering for engagement. I think it has contributed to a lot of the stress that creators feel these days, where they need to aggressively build big audiences in hopes of monetizing a fraction of them.

Patronage isn’t a free lunch, either, but there’s an important lesson here about building fewer but deeper relationships. I think more people should adopt a patronage mindset, beyond the context of online creators. Taking care of the people in your life who matter is important. Before we expected the government to provide safety nets – a fairly recent historical development – wealthy people took care of everyone in their household. To me, the message is: treat people well and share your fortunes generously. I think that’s the only way to feel true happiness from success.

What experiment would you run if you had unlimited resources and no operational constraints?

I’ve been learning how people’s subjective experiences are mostly decoupled from external circumstances. That might sound like a truism, but in practice, we tend to promote ideas like: people who work hard are also very stressed, or anxiety is justified when the situation calls for it. But in my current line of research, I’ve been fascinated to see how people’s inner states appear to be quite independent from their material conditions.

So, I’m very curious how to help more people recognize this and learn how to reliably access and sustain positively valenced states, regardless of what’s going on in their lives. I think we have some incredible tools at our disposal right now, both on the neurotech side and among contemplative practices like advanced meditation. But we still know shockingly little about how these interventions really work, or what their lasting impact is.

What is the most significant thing you’ve changed your mind about over the past decade?

How rewarding – and genuinely fun! – it can be to build a marriage and a family. I wouldn’t say I was explicitly against it in the past, but I underappreciated how much it actively improved the rest of your life.

People often talk about “settling down” and starting a family as if they are at odds with our personal ambitions. But although families certainly create more work on a practical level, I’ve found that they also make my priorities obvious in a way that is calming and clarifying. I think it’s made me less afraid to pursue new ideas with work, too, because now I know what really matters, and I’m not afraid to take risks.

What craft are you spending a lifetime honing?

Mastering eye contact. I’m terrible at it! I’ve tried all the tricks, and still I struggle.

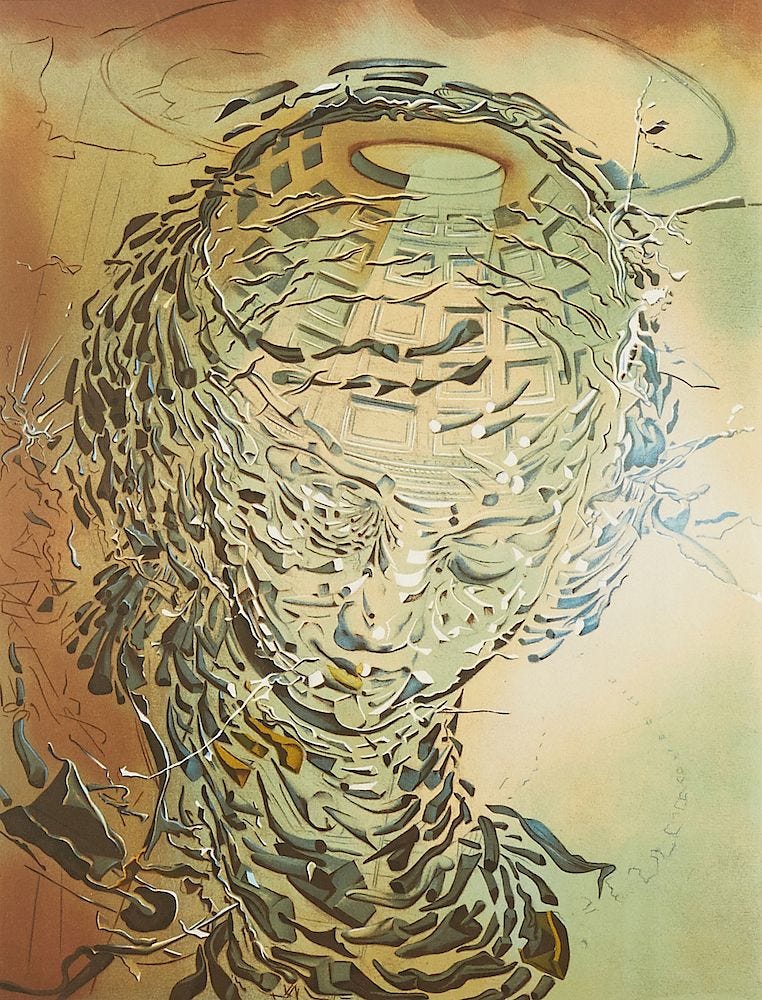

What piece of art can you not stop thinking about?

A framed print of Salvador Dalí’s “Cosmic Madonna” has hung above my desk for years. Dalí produced a series of works under this title during his “nuclear mysticism” phase, following the United States’ development of the atomic bomb, which sparked his curiosity about the relationship between physics and the mind, which he realized were composed of the same matter. Dalí spent years exploring a philosophical interpretation of quantum mechanics, which he thought could reveal new insights about our consciousness and how our seemingly disparate experiences are connected.

I grew up gazing at this print for years throughout my childhood, which hung in a relative’s home. I inherited it when he passed away. The piece feels very fitting to me now, given my interests, but I knew nothing about its backstory when I was younger. It’s funny how art chooses you, before you can even articulate its significance.

What is your most contrarian, high-conviction opinion?

I find that this one is not widely accepted among tech circles, but: I think that young people should spend their days having life experiences, more so than prioritizing career games. It’s, of course, important to pursue one’s interests and be ambitious with your goals, but I so often meet people who focused on maximizing a narrow set of life outcomes instead of forming their identity, and that becomes much harder to do when you’re locked in mid-career. Youth is a privilege: use it to experiment, test the boundaries of the world, and make stupid mistakes.

What risk are we radically underestimating as a species? What are we overestimating?

I think we’ve still underestimated the harms of scrolling. I am careful to say “scrolling” because I don’t think social media is itself a bad thing, nor do I think screens are uniformly bad. I think it’s specifically the act of scrolling, which forces us to ingest, process, and respond to an insane firehose of ideas. I don’t think all this micro-context switching is good for us; we’re collectively destroying our attention. Most people know the feeling when they’ve scrolled too much and it makes them feel kind of exhausted and bad, yet for some reason, suggesting that something should be done about this behavior – I’m still agnostic as to what – makes people upset and defensive. I think being perpetually distracted as a species is a very bad thing, and it has downstream effects on everything else.

I always think people overestimate the importance of day-to-day politics. To quote a university president who spoke at a conference I attended this year: politics are always upon us in every moment, but when people look back at this time, they’re not going to talk about politics. They’re going to talk about this moment as a technological revolution that created an economic one and the implications of that.

If you had the power to assign a book for everyone on Earth to read and understand, which book would you choose?

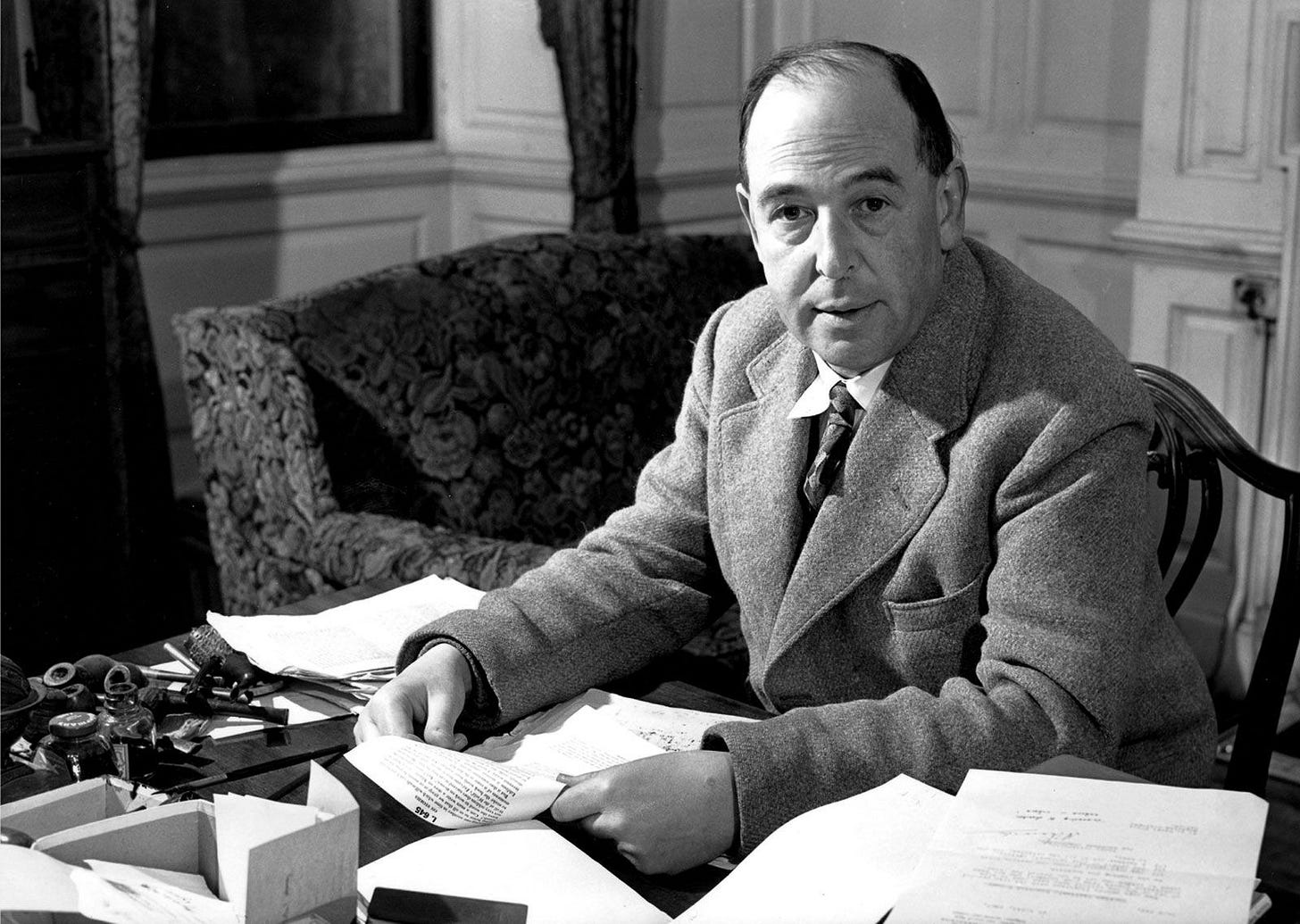

Gosh, it’s hard to pick just one! I’ll go with C.S. Lewis’s Surprised By Joy, which chronicles his conversion from being raised Christian to becoming atheist to then rediscovering Christianity as an adult. I’m not sure I would have understood this book earlier in life, but when it did click for me, it was very profound. C.S. Lewis is a terrific writer who somehow manages to write about these topics in a simple, approachable manner.

Although it’s rarely acknowledged, grappling with spiritual matters is, or should be, an adult rite of passage. John D. Rockefeller, for example, believed that his duties were to God first, then his family, and then his work. I think this is a good way to live. Many people were raised in a certain faith by their parents but let it lapse as teenagers and adults. As we get older and have more life experiences, I think it is important to re-confront these questions that we perhaps weren’t able to fully grasp the importance of when we were younger. It’s sort of like the difference between the politics you were raised in versus choosing your politics as you get older.

What’s an underappreciated corner of the internet?

I’m a fan of the humble email inbox, which is often dismissed as a clearinghouse for scheduling meetings and unsubscribing from marketing emails. But amidst all that clutter, it’s also an intimate space to trade thoughts with friends and strangers. Technology moves fast, but I find something reassuring in the idea that these older channels of communication still exist and are available to us. Their constraints also encourage my brain to think in different and surprising ways. Emails are wonderful if you and the other person assume there is no appropriate time limit with which to respond. Respond whenever you find a quiet moment, even if it’s weeks or months later. When I send a personal email, I never expect a reply. I’ve revived years-old email chains with friends, and I’m always delighted when someone surfaces one of those chains back to me.

In general, I worry about the long-term future of longform writing. People have been unsuccessfully proclaiming its death for years, and longform always finds a way to persevere. But I worry that our attention spans are getting shorter. And so I try to keep using longform communication instead of bowing to social pressure to compress my thoughts into character limits, and I’ll keep doing it until someone pries it from my hands.

How will future historians describe our current era?

Chaotic, a bit lost, but amazingly generative in the long run. There’s more noise, yes, but that also creates room for more outliers and more upside. I have to remind myself of this: I often feel daunted by the chaos, but there’s still so much beauty to discover.

The Generalist’s work is provided for informational purposes only and should not be construed as legal, business, investment, or tax advice. You should always do your own research and consult advisors on these subjects. Our work may feature entities in which Generalist Capital, LLC or the author has invested.