Actionable insights

If you only have a couple minutes to spare, here’s what investors, operators, and founders can learn from Rappi.

Going multi can work. Most startups pick a narrow focus and grow from there. Rappi has taken a different approach, competing across multiple verticals from the beginning. That's paid off for the company.

You can raise too much money. Really. Many of Rappi’s issues stem from its $1 billion injection from Softbank in 2019. The funding invited pressure and encouraged unsustainable spending on customer acquisition.

Delivery in Latam is a special game. The unit economics of delivery vary considerably across markets. Latam benefits from favorable dynamics, with relatively high average order values and low labor costs.

Keep an eye out for Latam’s giants. The region is full of fascinating businesses that have escaped many foreign investors’ attention. For example, one of Rappi’s most significant competitors is iFood, a business that has dominated Brazil’s food delivery market. It is rarely discussed outside the continent.

A referee?

Was that really what the customer had ordered?

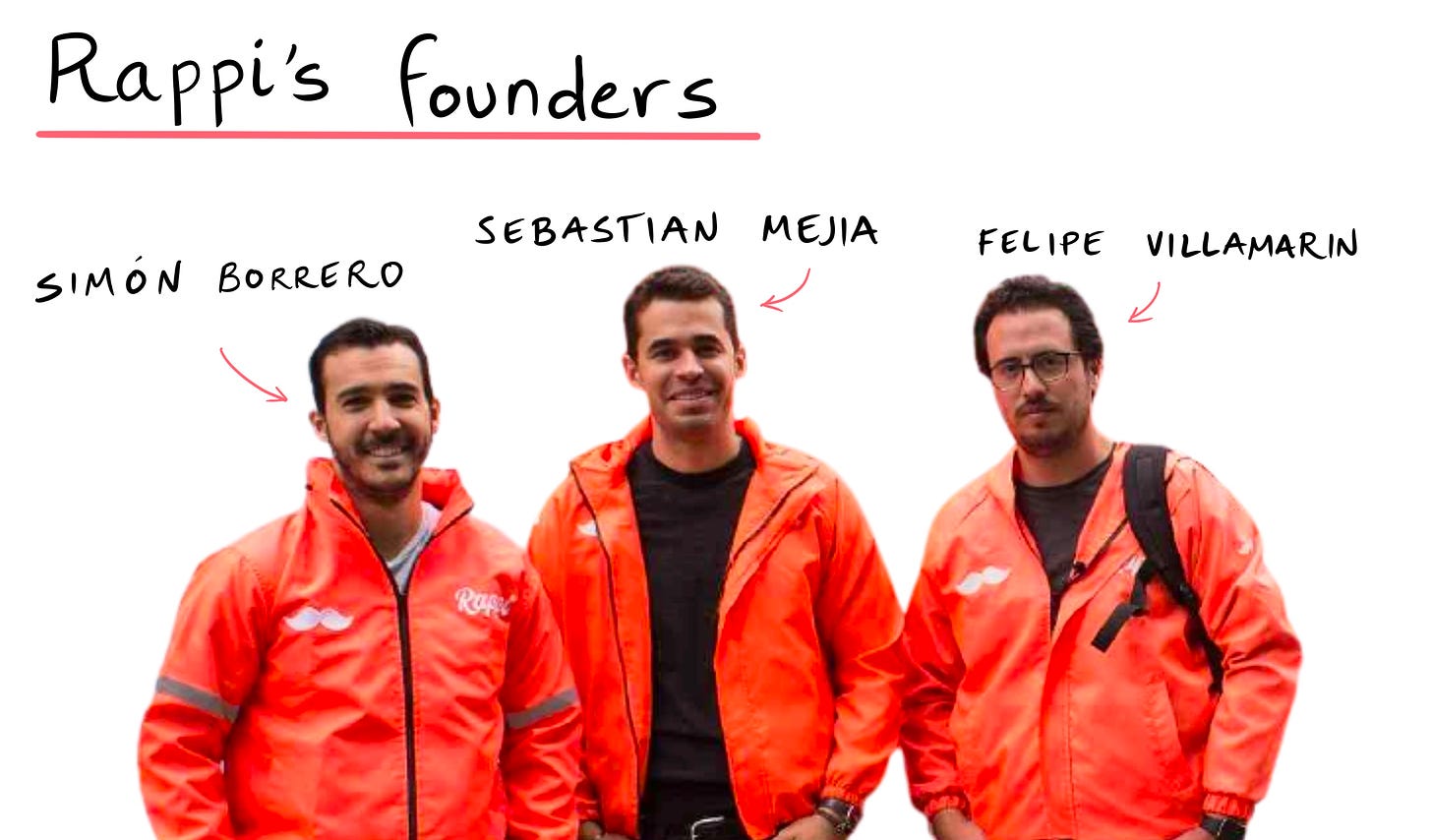

When Simón Borrero, Sebastian Mejia, and Felipe Villamarin had founded their on-demand delivery app, Rappi, they had braced themselves for all manner of strange requests. Indeed, they wanted them. The early designs of Rappi catered to the free-form and obscure, replacing the menus of most ordering apps with an open-text form. Rather than pick from a set selection, customers could ask for anything they wanted and Rappi would deliver.

The trio had seen all manner of requests come through since launching “Rappi Whim”: food, electronics, medication, clothing. It had been valuable to understand demand and build a direct, more intimate relationship with customers. Indeed, it was a vital part of the team’s early customer-obsessed strategy.

Despite that notable variety, the request must have nevertheless surprised them. But no matter how many times they read the message, it remained the same:

A customer was playing a soccer game somewhere in Bogotá and needed a referee for the match. Could Rappi deliver one?

Yes. Yes, they could. Somehow, somewhere, the team found a willing official, and brought them to the match in time. Rappi delivered.

In the six years since its founding, the company has continued to do that while scaling across nine countries, more than 100 cities, and millions of customers. It has done so up the steep Andean hills of Bogotá, off the happy beaches of Rio de Janeiro, down the broad avenues of Mexico City, and along Lima’s talking river. It has lifted drones in Quito’s thin air, and swarmed Buenos Aires’ elegant streets with bicycles.

Through bad weather, bad customers, political unrest, and economic turmoil, Rappi has delivered.

The scope of Rappi’s operations — coupled with the story of the referee, shared by an investor — give us a sense for the company and what animates it. This is a business that has, from its first days, placed huge importance on listening and learning from customers; from treating Latin America as unique, worthy of more than an “Amazon for X” or an “Instacart for Y.” It is a business that is proudly local, an organization that wants to be (and is perilously close) to being a homegrown hero.

And it is aggressive.

Rappi’s birthplace of Colombia is too often associated with the brutality and faux-glamor of Pablo Escobar, but in its desire to bring the fight to its competitors it more closely resembles another narcotraficante, albeit of the fictional variety. Rappi is Latam’s Walter White, an apex-predator in the making, playing on the front foot. They are the one who knocks.

That aggression has been a drawback at times. Yes, Rappi has achieved admirable scale, but they have done so at a steep price. Surpassing a $5 billion valuation is impressive in the abstract, but is much less so when the company in question has raised more than $2 billion. Capital inefficiency of that kind invites unfavorable comparisons and nourishes Rappi’s great bugbear: profitability.

While Rappi claims to be healthy from a unit economics’ perspective, it bears many of the hallmarks of the too-large, high-burning behemoths that public investors have viewed with skepticism at IPO. As the company prepares for its own debut, it has plenty left to prove: that it has control over its acquisition costs, can successfully layer on new, high-margin services, and will win pivotal markets that hang in the balance (see: Brazil).

We’ll look to explore these open questions in today’s piece, discussing:

Origins. How a childhood friendship led to Rappi.

Market. The unique math of on-demand in Latin America.

Product. Rappi’s multi-pronged approach.

Investors. Softbank’s burdensome capital.

Financials. The tactics Rappi is using to grow its margin.

Downside. What Rappi should fear.

Vamos.

Origins: A man walks into a bar

Along South America’s Pacific coast sits one of Colombia’s most romantic cities: Cali. Known for its warm weather, salsa dancing, and “Cristo Rey” statue, reminiscent of Rio, the country’s third-largest metropolis can now lay claim to two of the continent’s most prominent entrepreneurs: Sebastian Mejia and Simón Borrero.

"Simón and I go way back. We're high school friends,” co-founder Mejia told me over a call. Though Borrero was a year older, the pair were nevertheless “friendly and close,” a comfort that would prove critical years later.

After high school, the duo pursued different paths with Borrero staying in Colombia while Mejia moved to Europe. The diversity of their experiences was meaningful in Mejia’s view — while he developed a more global outlook, Borrero stayed in touch with the reality of living and working in Latin America.

While Mejia built a career in finance in New York City, Borrero decided to start a business in Bogota. Founded in 2007, Imaginamos, was a dev shop that provided services to food and beverage, e-commerce, and on-demand businesses. Traditional work included building websites or setting up a CMS or ERP. That proved lucrative, with Imaginamos growing to support more than 300 employees.

Those weren’t the only projects Imaginamos undertook, however. Early on, Borrero showed a knack for sniffing out areas of opportunity beyond the confines of contract work. One such project became the basis for he and Mejia’s first collaboration.

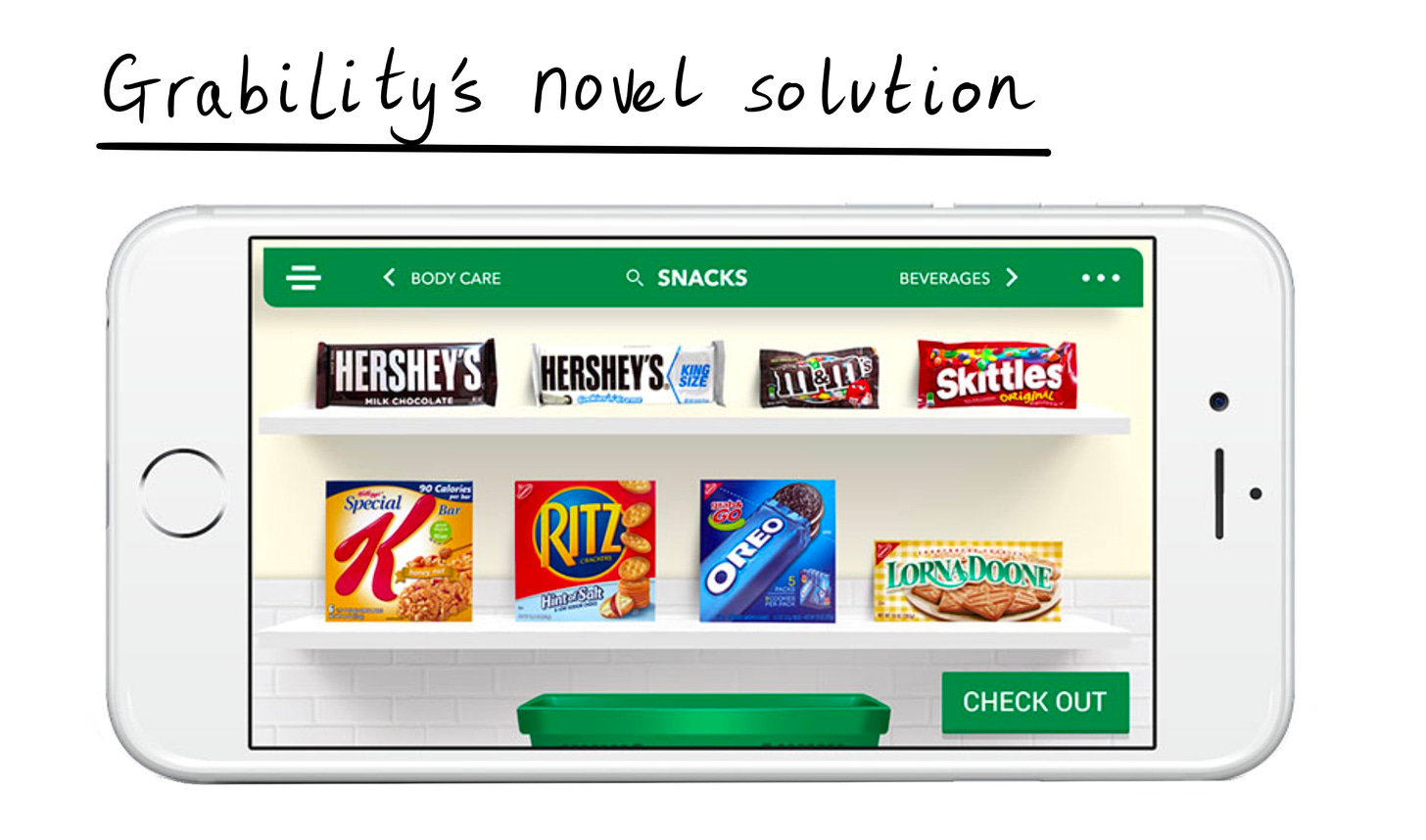

In the lead-up to the Christmas holidays, Borrero and his team built an experimental product. It was a little thing really — a digital shopping interface that actually looked like a shelf. Instead of navigating a cascade of menus and filters, users could simply select a skeuomorphic version of their item to place it into their cart.

Back in Cali for the season, Mejia decided to visit a bar one evening. It would prove a fortuitous decision; Borrero was there, too.

It had been a while since the two friends had seen each other, and they caught up on the last few years. Mejia had been looking for a chance to get into the world of tech and entrepreneurship, and when he heard about Borrero’s newest project, he sensed there was something in it, something bigger.

Over drinks, the pair sketched out the beginning of a partnership that would become their first startup: Grability. Based in New York, the company raised $2 million to sell Borrero’s interface to retailers making the move online.

Though they succeeded in constructing an intriguing solution and secured contracts with some of the world’s largest department stores, Borrero and Mejia sensed something was missing. Sure, they could provide software to retailers, but was that really what was needed? Who was doing the hard work of actually storing and delivering the products?

When they thought about their home continent, in particular, that seemed like the real opportunity, the true gamechanger. Perhaps, they thought, they should experiment with something different. The seed of Rappi had been planted.

Market dynamics: Latin math

Every market has its own, peculiar mathematics. What works in one geography, in one sector, often does not work in another. Borrero and Mejia were surely aware of the dynamics at play in Latin American prior to founding Rappi. In particular, they would have thought about four dimensions:

Market size

E-commerce penetration

Average order value

Labor cost

Let’s work through these.

First, market size.

While more investors are waking up to the scale of the Latam opportunity, it's still worth emphasizing. Brazil alone boasts a GDP of $1.4 trillion, followed by Mexico with $1.1 trillion. In total, the region’s GDP comes to $4.4 trillion, a figure that places it ahead of Germany, the world’s fourth-largest country by GDP. It comfortably exceeds India’s $3 trillion sum.

Such comparisons are slightly fatuous, of course. A continent is not a country, and the complexity of winning a region is exponentially higher than conquering a national market. Still, it gives us a sense of the prize.

A source close to the company shared Rappi’s internal market sizing figures which indicate the company pegs the TAM at $1.1 trillion, composed of $88 billion in pharmacy goods, $243 billion in food services, $389 billion in grocery, and $331 billion in retail.

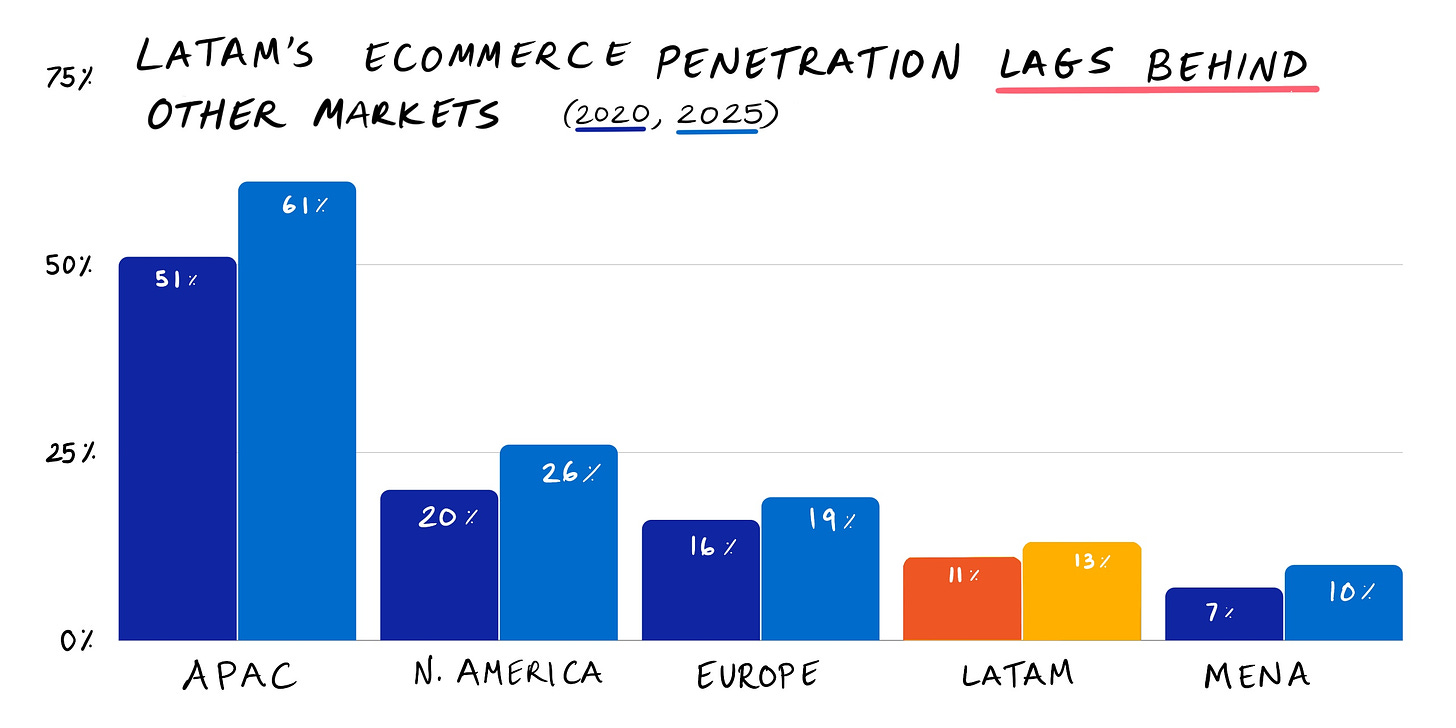

Part of the reason the opportunity is so compelling is that it is relatively under-addressed by technology. Barring the Middle East and Africa, Latin America has the world’s lowest e-commerce penetration rates, at 11%. That trails Europe (16%), North America (20%), and is barely in the rearview mirror of the Asia-Pacific region (50%).

While Statista suggests penetration will grow 2% over the next 5 years, Rappi is internally expecting Latam to reach at least 25% adoption (though without a set time horizon). That figure would bring $154 billion of GMV online if we adhere to the $1.1 trillion figure noted above. Should the region one day reaches parity with APAC, $429 billion would be newly up for grabs.

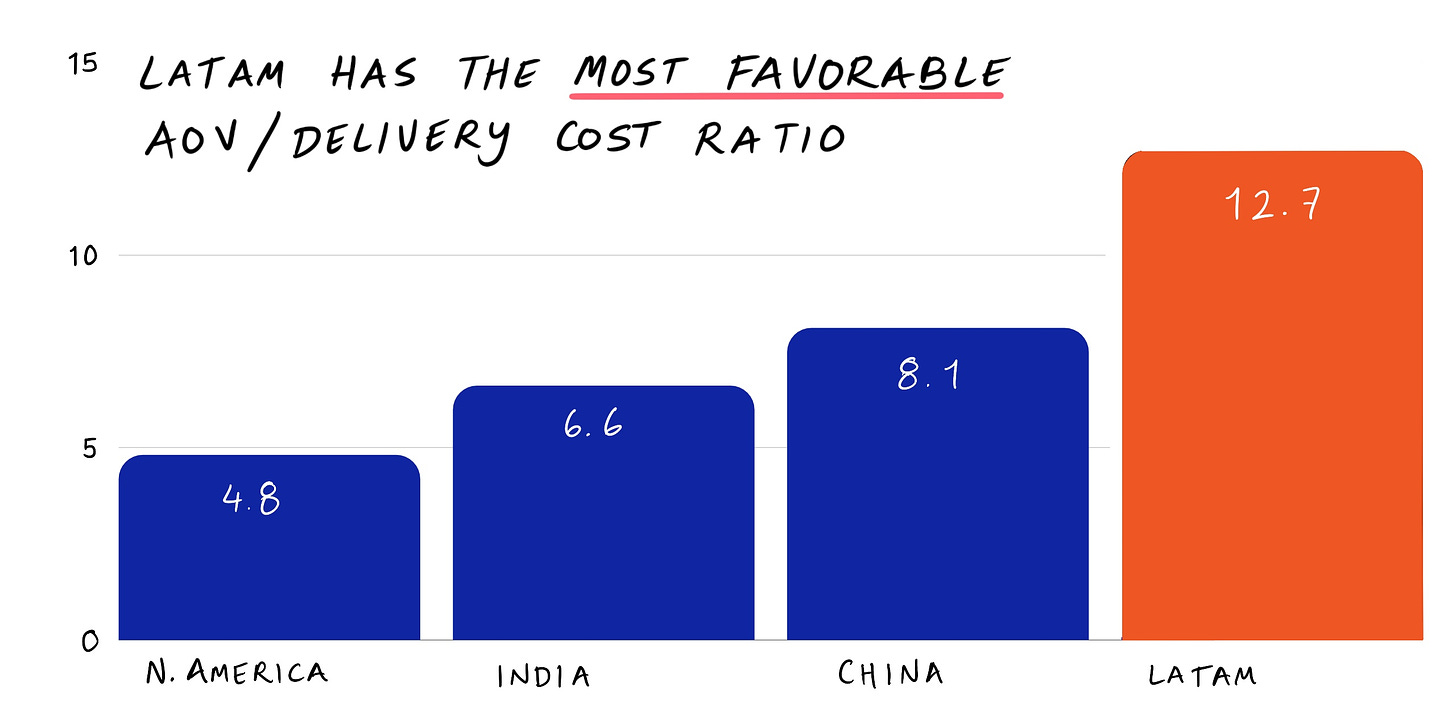

Rappi's founders may have been even more enchanted by the unit economics. As one long-time investor explained, Latin America is a truly unique market for delivery. While that’s true for many reasons, chief among them is the dynamic between average order value (AOV) and labor costs.

America is the home of high AOV — Doordash’s, for example, comes in at $31. Compare this to similar companies in other markets: Swiggy, an Indian delivery giant, has a $5 AOV, while competitor Zomato comes in at around $5.50. Chinese behemoth Meituan averages $6-7.

The likes of Swiggy and Meituan can bear this slim AOV because they benefit from low-priced local labor. While delivery in the US costs roughly $6.50, Chinese and Indian companies can achieve the same result for less than $1.

Latin America, and Rappi in particular, is a special case. AOVs for the region approach $20, with Rappi’s own figure pegged at $19. Meanwhile, delivery costs are still low, at roughly $1.50.

This combination is powerful: companies like Rappi can secure AOVs that approach North American rates while paying prices not too far from those of Eastern peers. The result is an incredibly favorable ratio between AOV and delivery cost.

Though many others seem to have missed it, Borrero, Mejia, and Villamarin had the perfect environment in which to start Grability’s successor.

Product strategy: Thinking multi

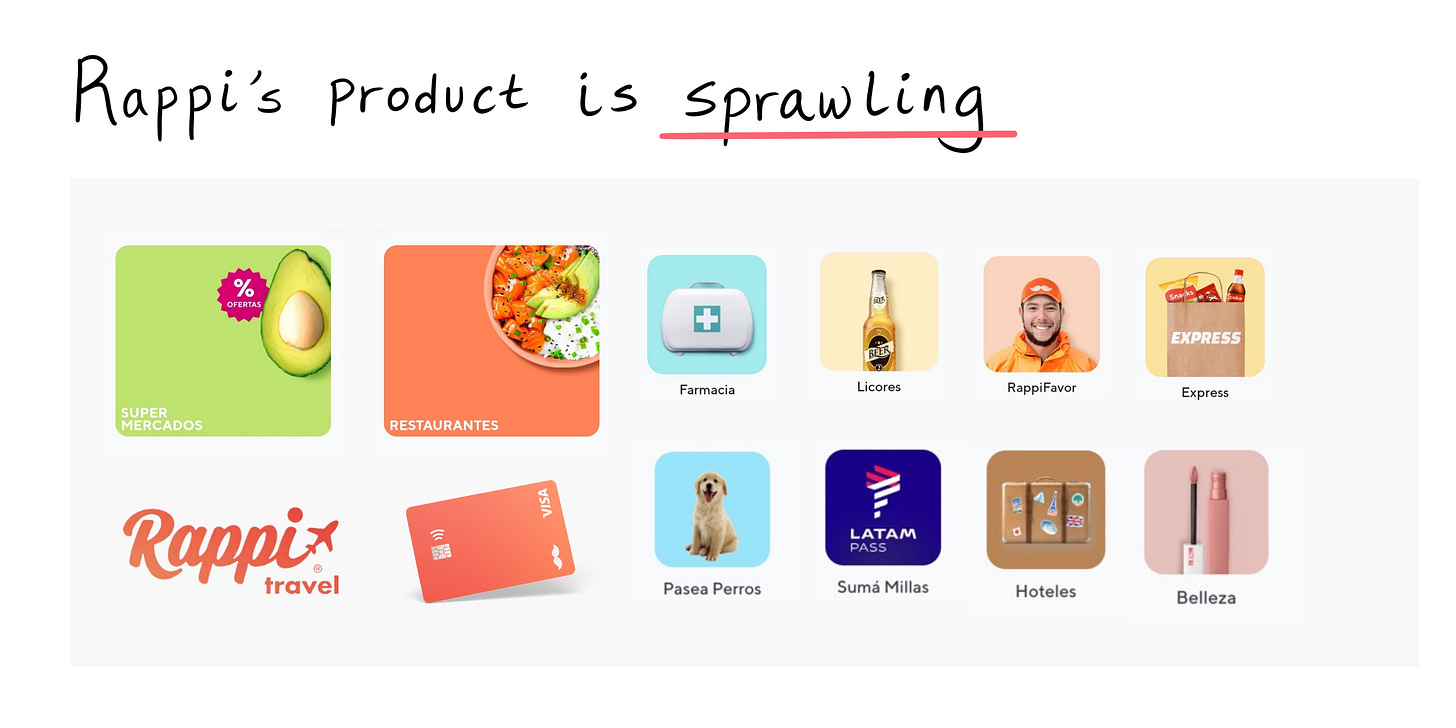

From the very beginning, Rappi’s founders wanted to build something bigger than just a food delivery company in Colombia. Instead, Rappi pursued a “multi” strategy, attacking multiple verticals and multiple markets from the outset. We’ll discuss both parts of that approach.

One of Rappi’s earliest investors noted that this multi-vertical strategy was present even during initial meetings, marking out the founders as particularly visionary. Indeed, it’s worth remarking on how unusual this is. Startup dogma preaches that founders should focus early on, picking a relatively narrow domain and attacking it as effectively as possible. Even mature companies demonstrate this tendency; it took Uber six years to add food delivery to its core ride-sharing premise, for example.

Rappi’s decision here reflected the founders’ ambition as well as an unusually mature understanding of both the market and dynamics of a delivery app. As Mejia mentioned to us, the team knew Latin America was a relatively bandwidth-poor market. Unlike the US or Europe, customers didn’t want to download multiple apps; many preferred a single portal that fulfilled multiple needs without taking up too much memory or data.

Equally, Borrero and co. seemed to recognize the magic of super-apps from the outset. As discussed in our coverage of Kaspi, multi-pronged companies benefit from a relationship between LTV and CAC that not only improves over time but does so in a stairwise fashion, rather than a gradual one. Existing business lines attract increasing spend, but each new product layered onto the core adds fresh revenue.

Over time, Rappi has developed a mature suite that touches a range of categories including grocery, pharmacy, food delivery, apparel, electronics, liquor, convenience store items, baby care, beauty products, flowers, flights, and toys.

That’s joined by a host of other offerings, including an advertising product, gaming practice, and a Task-Rabbit-style service (RappiFavor) that promises to handle everything from walking your dog, going to the bank, or picking up a package.

No doubt, Rappi’s comprehensive product has played a starting role in its expansion across Latin America, though it is far from the only driver. Just as Borrero and Mejia were adventurous in embracing a multi-vertical approach early on, they also saw Rappi as a multi-market play.

In our conversation, Mejia noted that after launching in Colombia, Rappi immediately moved to address the larger Mexican market. Since that initial expansion, Rappi has grown to seven more countries: Brazil, Argentina, Uruguay, Paraguay, Ecuador, Peru, and Costa Rica. Gaining share in those markets has required a range of tactics.

Growth: Winning tactics

Identifying a business’s playbook can be a dangerous game, particularly for a business like Rappi. The company has had to find different ways to win — across terrains, cultures, market conditions, and political climates — many of which may not fit neatly into so rigid a structure.

Still, there seems to be a coherent set of tactics and values that have aided growth. In particular, Rappi has thrived by embracing four tenets:

Signing exclusives

Architecting density

Providing exceptional service

Competing on price

In researching this article, we spoke to multiple current and former Rappi employees. One of those individuals helped manage the Andean region, which includes Ecuador. Per this employee, though Rappi entered Ecuador late, with three competitors already in place, it has quickly ascended to challenge for the number 1 spot.

When we asked what explained this rise, they cited the company's partnership capabilities. Rappi seems to excel in this regard, snagging exclusive agreements with key restaurants and convenience chains. For example, Rappi’s grip on the Mexican market has been aided by partnerships with 7-Eleven, Dairy Queen, Shake Shack, and others.

Winning deals like this can be pivotal in bootstrapping a new region, helping to create necessary density. As we’ve noted, Rappi’s strategy is for customers to use its app to purchase just about anything. That doesn’t work if the company can't provide a sufficient number of options within a certain area. While a customer in Fortaleza, Brazil might use Rappi to order a pizza one week, if they return the next and can’t find a decent sushi spot, they’re likely to redirect their efforts (and future orders) to a national player like iFood. Rappi internal data shows the company has studied the impact density (in the form of active stores) has on conversion rates, with close to a linear relationship between the two.

As one investor described it, “It's harder to get to the magical ‘Rappi solution’ without density."

If Coupang is the gold standard in exceptional service ( we have not found a company quite like it), Rappi is not too far behind. Many sources emphasized how effectively Rappi serves its customers.

For example, the employee we mentioned earlier noted that Rappi had less than a 1.5% “defect rate” in Ecuador, meaning fewer than 2 of 100 orders received a customer complaint. This was aided by best-in-class delivery times. Both apparently compared favorably to incumbents and were important in stealing share.

Skeptics will point to the final lever Rappi uses to attract customers: price competition. For most of its life, Rappi has benefitted from having money to burn. That’s given it the ability to underprice competitors and buy users. Such a tactic is not always well-deployed, of course. For one thing, though well-capitalized, Rappi’s war chest pales in comparison to a competitor like Uber. For another, acquiring customers unsustainably can hurt more than help. That’s a lesson Rappi has had to learn the hard way.

Investors: Softbank and CAC derangement

Dunking on Softbank is something of a professional pastime in the venture capital community. Such complaints can feel tiresome after a while, but the firm’s investment in Rappi is a reminder of such criticism's merit.

Though Softbank may be adhering to a more sophisticated approach these days, its early venture activity violated the minimum standard investors should hold themselves to: do no harm. Forget vague promises of being “value-add,” it is an adherence to the Hippocratic oath, famously required by those in the medical profession, that should be the base expectation.

Softbank’s failure to reach this threshold arrived in the form of a $1 billion investment in 2019. Already, by that point, Rappi had constructed a cap table that would make many founders envious — securing early backing from Y Combinator, pulling in a16z at the Series A, and snagging Sequoia at the Series C. Investments from Delivery Hero and Yuri Milner’s DST Global followed.

While it’s fair to wish that Borrero, Mejia, and Villamarin had shown greater restraint in the face of Masa’s billions — choosing the path of sanity and sustainability — wild optimism is more often a strength than weakness among entrepreneurs. The same ambition that gave Rappi the belief it could conquer a continent likely gave the trio the sense that it could make good use of Softbank’s steroidal injection.

Instead, it fomented instability.

Several sources referred to this funding as the genesis of Rappi’s worst impulses. Pressured by its investors, Rappi looked to grow manically. That mission quickly relied on unsustainable channels, with the company resorting to heavy discounting — selling a burger for $2 that should have cost $5 — to attract new users. As one investor noted, “[Rappi started to] buy orders at all costs. That's not the game here."

Though new user numbers looked good in the short term, many failed to stick around. Cohorts from this period are apparently rather disappointing.

Softbank’s investment also seems to have had a negative impact on Rappi’s culture. One former employee noted that the capital influx didn’t come with much direction from above, creating an environment of high stress in which leaders’ demanded results but failed to provide instruction. When I asked this same individual what Rappi’s weaknesses might be, they responded, “I think that a lot of important people within the company are a little bit tired or burnt out.” That fatigue seems to stem from Softbank’s entrance.

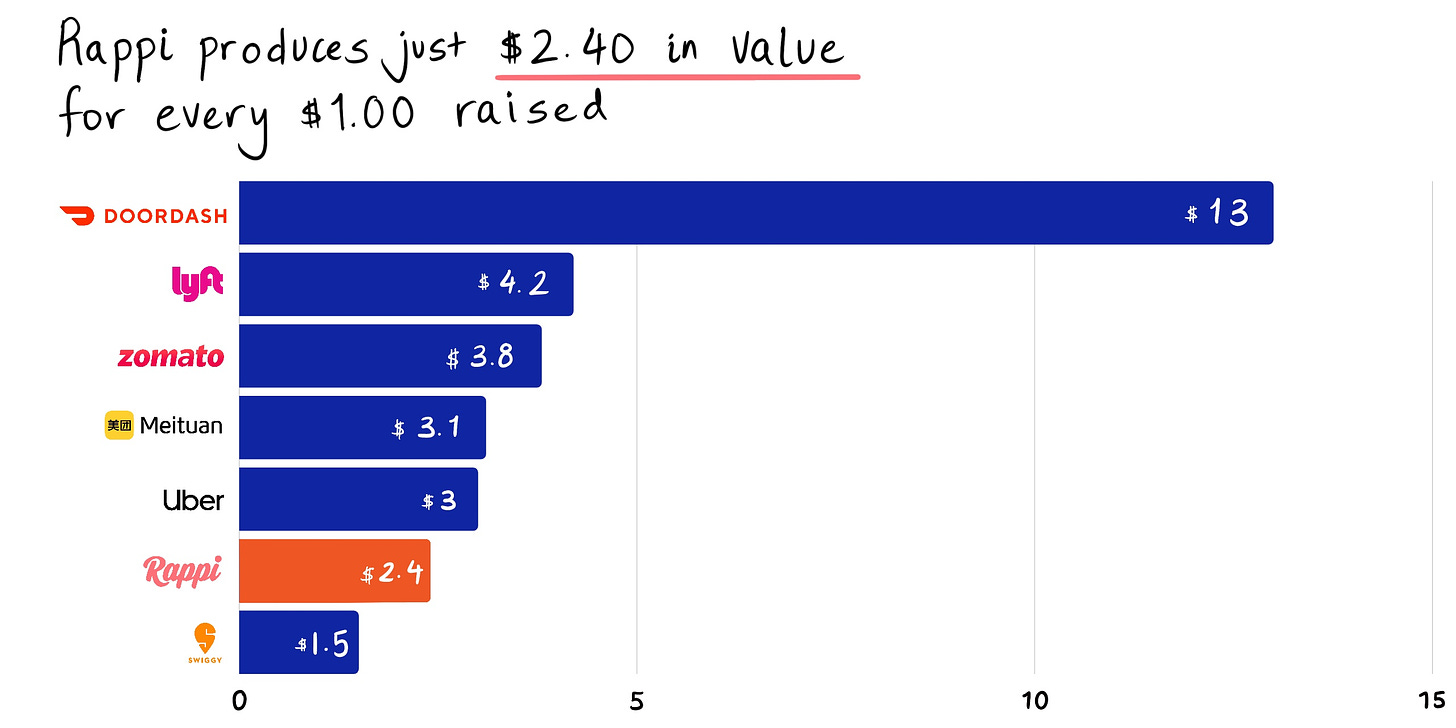

Rappi still bears the marks of this period. Questions about the company’s profitability remain, and as the source above alludes to, it could lose key figures prematurely. Distressingly for potential public market investors, Softbank’s funding also gives Rappi the veneer of an inefficient capital allocator. For every $1 in private funding received, Rappi has created just $2.40.

That’s not terrible, but it places it toward the back of the pack. Only Swiggy — another recipient of a recent Softbank mega-round — has received less bang for its buck.

Rappi has yet to answer questions about its internal investing skill and its profitability. But looking at its recent moves, it’s clear the company is beginning to devise ways to increase revenue and expand margin.

Financials: Margin games

Though Rappi operates across categories, if we needed a short-hand, it would not be too far off to call it an on-demand deliverer of food and groceries. Those are the two most significant parts of its business and both are low-margin. As Mejia himself said, “It's a business of basis points, a business of cents."

That is not to say there isn’t a difference between the two. As outlined by a Rappi investor, the categories have divergent unit economics. Because of Rappi’s ability to extract a comparatively high take rate from restaurants, the company can approach 5% EBITDA margins on food orders, providing at least some room to maneuver.

Grocery is a tighter game. One solution is to redirect demand toward higher-margin convenience store products. Rappi is making aggressive moves into this space, targeting “10-minute delivery.” It’s doing so by building out a web of dark store locations. Internal sources indicate Rappi had at least 57 dark stores live with more than 450 expected by the close of 2021.

Another solution is to add a new revenue stream to the grocery ordering process. Though disguised as a grocery delivery platform, Instacart may be better understood as an ad network. The company reportedly breaks even on its core offering, making its money by selling promotional space in its app. This can end up being meaningful — up to 5-10% of GMV.

Rappi has started to roll out an ad service across food delivery and grocery, targeting a 15% increase to its contribution margin by the end of the year. The recent introduction of Rappi Travel — which one employee claimed equaled Expedia in terms of selection in relevant markets — will offer more ad inventory in a high AOV category.

Advertising is not Rappi’s only attempt to layer on margin. Aping Amazon, Rappi has launched its own “Prime” product for a monthly subscription fee. Customers receive added customer support, access to special deals, and a special credit car. While there are some costs incurred in offering this service, it is a radically different proposition from grocery. It has gained reasonable traction so far, with Rappi projecting 2 million Prime members by the end of the year.

As the Prime offering indicates with its inclusion of a credit card project, Rappi is also dabbling in fintech. This is a well-worn path for commerce super-apps, and Rappi should feel confident it can make at least some headway given its established user base and Latin America’s large unbanked population.

Thus far, Rappi has partnered with banks like Interbank and Davivienda to offer the “Rappi Card,” a credit card with no fee. It’s unclear how much uptake the offering has gotten, though internal reports project 1 million cardholders by year-end.

Rappi has taken a leaf out of Sea Group’s book, too. The Southeast Asian giant has rapidly scaled its Shopee app in Brazil (and beyond) by gamifying the shopping experience. Customers can earn Shopee rewards by playing games within the app — a feature that improves conversion, time on the app, and frequency of usage. Thanks to its gaming division, Garena, which created mega-hit Free Fire, Sea is especially well-placed to offer this quirk.

Rappi seems to be experimenting with these kinds of features, adding music, games, and a live shopping experience under the banner of "Rappi Entertainment." While it's something of a stretch, it’s not impossible to imagine Rappi turning these products into revenue-generators; rather than games serving as a form of customer engagement, Rappi may be able to monetize players, as Sea does.

But before Rappi builds its own battle royale blockbuster, it must first win the Brazilian market.

Key market: The battle for Brazil

Rappi is “doomed.” That’s how one source described the company’s abilities to win the food delivery space in Brazil.

Indeed, across conversations, skepticism emerged of Rappi’s ability to triumph in Latin America’s largest market. That may partially be due to the cultural and linguistic differences that separate the region’s Portuguese-speaking nation; it’s also a recognition of the stiff competition Rappi faces in the form of iFood.

Founded in 2011, iFood is owned by Brazilian conglomerate Movile. That local understanding and considerable headstart has made the incumbent hard to move. The pessimistic contributor mentioned above noted that iFood had 11x the users, and 100x the city coverage of Rappi. They also noted that iFood boasted 15% EBITDA margins.

Rappi is trying gamely. In January of this year, the company reported having roughly 28,000 Brazilian stores signed, a figure they expected to 2.7x over the follow 12 months. Internal documents expressed hope that Rappi would reach 45,000 restaurants in the country by year-end, with nearly 20,000 in Sao Paulo alone. Will this be enough?

For now, iFood seems to have held Rappi off in food delivery. The good news is that the company is doing a considerably better job in grocery. Rappi counts Brazil as its largest market in the category and claims to be the number one player. GMV has grown 300% year-over-year (YoY), aided by partnerships with large chains and exclusive agreements with high-quality specialty stores.

Success in grocery may give Rappi the foothold it needs in Brazil. Over time, the company will hope it can chip away at iFood’s domination by converting users of its grocery service. It seems a long way off. But Rappi’s team is not one to be underestimated.

Management and culture: Smiling assassins

Though well-respected, there’s an undeniable intensity about Rappi’s culture. Much of that may come from management. While Borrero, Mejia, and Villamarin seem a likable bunch, it would be naive to think they’re anything less than high-performance operators on a mission.

Borrero is the pivotal figure, with one source noting that he is “running the show.” Looking to better understand what makes Borrero tick, we spoke with Colombian serial entrepreneur, Andres Gutierrez. The founder of Tpaga and Tappsi, an Uber competitor, described his contemporary as “humble, hard-working, persistent and with a huge vision.”

Gutierrez added that Borrero “has been smart enough to build a great team and network around him.”

Mejia is the most outward-facing of the founders. He cuts a charismatic, articulate figure, fitting given that his role is to focus on bringing in new business.

Villamarin completes the set, focusing on product and tech. He appears to be the junior partner among the three, both from an experience perspective and in terms of driving Rappi’s direction.

By and large, the trio seems to have forged an admirable culture at Rappi, albeit one with drawbacks. Among its strengths, Rappi appears to have a flat, ego-less culture.

One current employee highlighted this during our discussions, remarking that after joining the company, he was given the personal cellphone numbers of the three founders, and told to text or call them any time with his ideas. Across the company, junior employees seem to be empowered to Whatsapp seniors with questions or suggestions. As this Rappi employee described it, “I never hear anyone say ‘my boss.’ There are leaders, not bosses."

Another of Rappi’s cultural strengths is its “no job too small” mentality. One former office worker noted they had moonlighted as a delivery man when necessary. He shared several stories to this effect, including one that involved the whole local office:

It was a Friday evening at one of our offices and we were having a very fun happy hour, chatting and getting to know each other better…

All of a sudden someone comes by my place and says, 'Hey I think we have 400 orders in progress in just ONE brand, it’s a liquor store.' We had misconfigured a coupon code and a push notification was sent to more people than expected, therefore, more orders were placed.

We had two choices, either cancel those orders or distribute all of us in smaller teams and go to the stores to actually help pack and deliver the orders on time...We picked the latter and everyone from the head of growth at the time, to the country manager, to people that worked in our warehouse operations were all...pack[ing] orders at the stores. We delivered every order, no major issues or cancellations and we were happy, customers were happy, and the merchant made a shit ton of money that night.

Rappi seems to have built a sense of camaraderie and purpose amongst employees, demonstrated by moments like this one.

A final strength worth noting is the modernness of Rappi’s management. Though Latin America has certainly birthed incredible tech companies before Rappi — Mercado Libre and Nubank chief among them — the Colombian creation seems to have benefitted from its connections to Silicon Valley. The same former employee highlighted a few examples of this:

It’s the first company in Latin America that I’ve heard of that gave stock options compensation to its top (and not so top) employees, used OKRs, Slack, and a very modern tech stack.

Overall, Rappi’s culture seems to be a reflection not only of its founders global worldview, but of its deep passion for home markets.

Not everything at Rappi is quite so rosy, of course. As mentioned earlier, Softbank’s investment precipitated a fractious brand of management, with leaders pressuring employees to achieve unrealistic results, without much direction. A former Rappi employee described the culture, thusly:

It’s definitely on the more cutthroat end of the spectrum. It’s an aggressive company, obsessed with growth and a no-matter-how mentality.

When asked where Rappi might be vulnerable, the same employee referred to “Some characters within the internal culture.”

Leadership will have to keep an eye out for destructive "characters" to protect all the good work they have done. More serious issues are likely to come from elsewhere.

The bear case: Controversies and vulnerabilities

Despite the successes mentioned throughout this piece, it is not too hard to construct a bear case for Rappi. Though the company has plenty of room to run, there’s also an uncommon amount of uncertainty for a company its size. Four risks seem particularly worth noting:

Rappi may be doing too much

It may lose Brazil

Profitability may prove difficult

The brand could deteriorate

Rappi’s multi-vertical strategy comes with a catch: it's a lot to manage. While bundling groceries with food delivery adheres to a logistical logic, adding on orthogonal products like banking may prove a misstep. Rappi is taking on a great deal for a young company, particularly given its core business is unprofitable. Can it build a great financial app at the same time as it guides its other divisions?

Not all are convinced. Though Tpaga founder Gutierrez admits he has a bias given his own company’s financial focus, he was skeptical of Rappi’s play:

I don’t see how you can build a mobile bank while you are still building your core business. If you already have a dominant super app, like WeChat you [could do this]. But I think people fail to realize that building a valuable neobank is a lot tougher than it [seems].

The same logic can be applied across Rappi’s operations. Though having multiple product lines has benefits, of course, it also leaves room for Rappi to be unseated by focused, vertical competitors. Cornershop, for example, may steal share in grocery; Nubank, Albo, and Tpaga may seal off the banking space; iFood could further consolidate its food delivery business. The “super app” concept has worked in other markets, but it may not play out quite as smoothly in Latin America.

As we’ve noted, iFood is a particularly concerning competitor given its stranglehold in Brazil — any Rappi bear case is likely to incorporate the possibility of losing the country. Given Brazil makes up 32% of Latin America’s GDP, failure to secure an enduring position would meaningfully reduce the size of the opportunity available. Grocery seems to be going well but iFood offers services in this space, too. It acquired SiteMercado last year to bolster its offering. With a smaller national footprint — operating in just Brazil, Argentina, Colombia, and Mexico — iFood may be better able to focus on its home market.

This is without factoring in other competitors. Daki, the Brazilian subsidiary of grocery/convenience company JOKR, is another player taking the market seriously. LinkedIn data indicates the company has nearly 150 people staffed to this division, and given JOKR’s connections to Softbank — much of leadership hails from the company or previous portfolio companies— it is will have money to spend.

The effect of prolonged fighting in competitive markets may be that Rappi struggles to reach profitability within a decent time frame. This is one of the most commonly cited concerns about Rappi, and though rooted in reasonableness, feels as if it misses some of the company’s core strategy. Borrero has intentionally chosen growth over profitability, and with the exception of the Softbank farrago, that appears to have been the right move. It has allowed Rappi to attract capital from elite financiers, draw top-tier talent to its offices, fortify its product, and expand internationally. Though we can’t be sure without exact numbers, the sounds coming out of the company suggest there’s a line of sight to turning a profit. As we’ve discussed, the dynamics of the market make that far more possible than in many other geographies in which similar bets are paying out.

Still, it should not be discounted, and may nevertheless dissuade public market investors, depending on the valuation Rappi seeks at IPO.

Rappi’s final worry may be a reputational one. For now, it enjoys a stellar brand in the ecosystem — one that apparently wins affection from the everyman and commands cache in tech circles. One ex-employee shared their impression:

People absolutely love the brand...When I was working there it was even cool to work for Rappi. You would tell any friend/acquaintances you worked there and you’d definitely look good, be asked many questions...

Losing that favorable glow is possible. We’ve already discussed the unpalatable elements of Rappi’s culture that could provoke a backlash, but most criticism of working conditions has focused less on office workers, and more on gig laborers. Last year, delivery workers protested against Rappi and its competitors, demanding minimum wages, benefits, and better protections. While the companies in question still have plenty of gig workers, the resentments remain.

This is a complicated matter. While on-demand workers are subject to difficult and dangerous conditions, particularly during the pandemic, Rappi has undoubtedly had a positive economic impact on the countries in which it works. For one thing, gig work has few barriers to entry, something that has proven particularly valuable to the many Venezuelan refugees that have escaped to Colombia and beyond. Rappi and its cohort often represent the fastest way to begin earning a living, and often provide higher pay than other options. One employee noted that working for Rappi as a delivery person brings in 2x the minimum wage. (That figure could not be independently confirmed.)

Despite these benefits, some may believe they are outweighed by the costs, a feeling that could congeal into public animus. Rappi will want to ensure it retains the aura of the friendly local champion from which it has benefitted.

If constructing a bear case for Rappi didn’t require much of a stretch, a bull case takes even less. We need only return to where we began: this is a business with a sincere desire to serve its customers in a market that has barely gotten off the ground. If Borrero has guided Rappi to a $5.25 billion valuation in a Latin American market that has just 11% e-commerce penetration, what can he and his team achieve at 25% or 50%?

While Rappi may not be able to win every space it enters, it does not need to. If it can dominate food and grocery delivery across a handful of major markets, it is positioned to ride a wave that may see it, one day, approach Mercado Libre’s $80 billion market cap. Success in fintech, gaming, or some other endeavor would be a bonus.

It is not in Rappi’s nature to sit and wait. Rappi is the the one who knocks, after all. But if the company's success so far has relied on aggression and initiative, unlocking its true potential may require something different: patience.

The Generalist’s work is provided for informational purposes only and should not be construed as legal, business, investment, or tax advice. You should always do your own research and consult advisors on these subjects. Our work may feature entities in which Generalist Capital, LLC or the author has invested.