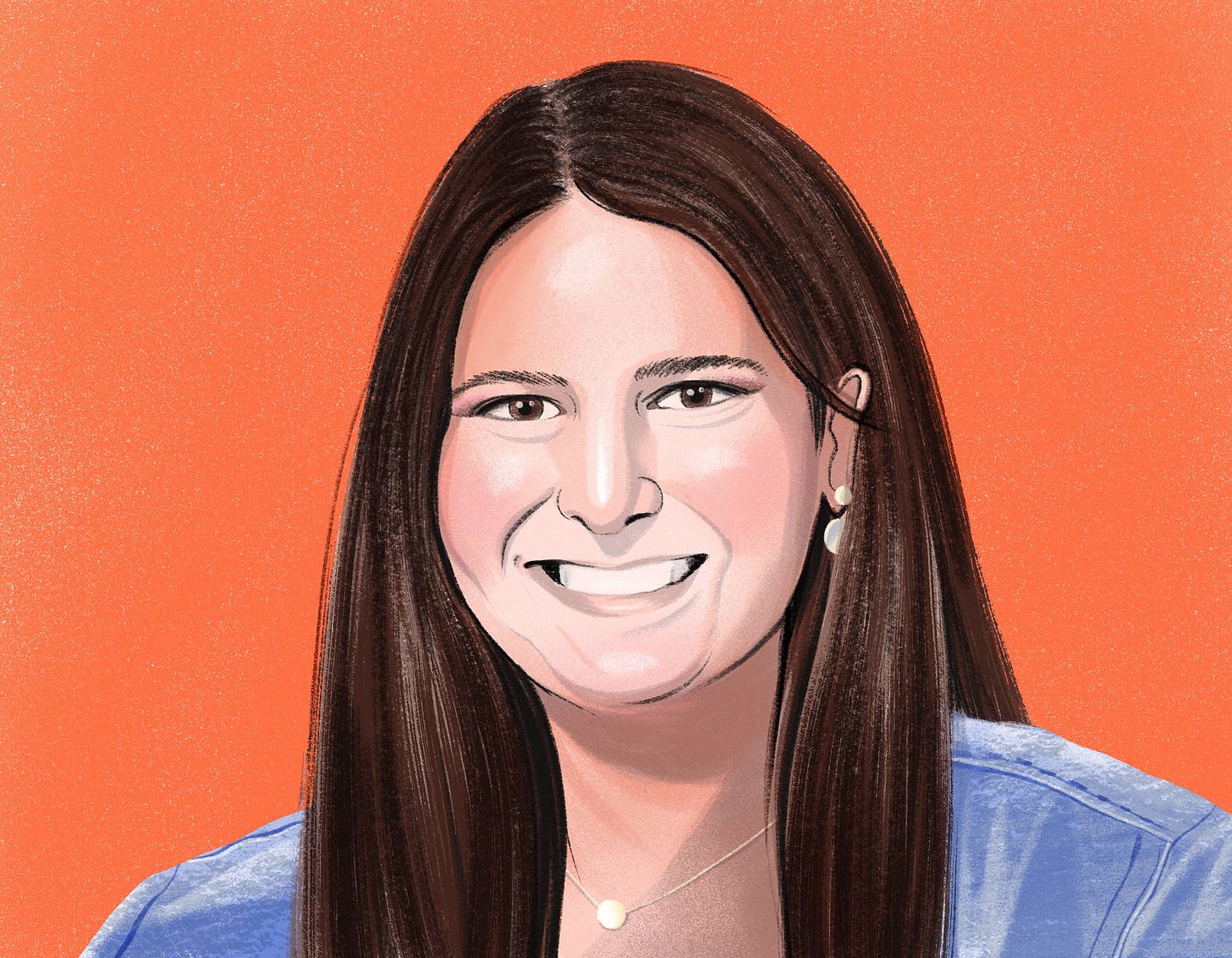

Modern Meditations: Rebecca Kaden

The Union Square Ventures managing partner on stories, ancient structures, and technological salvation.

Brought to you by Masterworks

A Banksy got everyday investors 32% returns?

We know it may sound too good to be true. But thousands of investors have profited, thanks to the fine-art investing platform Masterworks.

That Banksy return isn’t a one-off. Masterworks has built a track record of 16 exits, including net returns of +10.4%, +27.3%, and +35.0%, despite macroeconomic turbulence.

For those skeptical of the value to be found in the art market, here are some compelling figures. Contemporary art prices…

Outpaced the S&P 500 by 131% over the last 26 years

Have the lowest correlation to equities of any asset class, according to Citibank (1985-2020)

Remained stable through the dot-com bubble and 2008 crisis

Eager to diversify your portfolio? The Generalist readers can skip the waitlist with this exclusive link.

Actionable insights

If you only have a few minutes to spare, here’s what investors, operators, and founders should know about Rebecca Kaden’s meditations.

The power of stories. Before entering the world of venture capital, Rebecca Kaden worked as an editor at Narrative magazine. Though investing and publishing may seem like worlds apart, the Union Square Ventures GP sees similarities. Both editors and investors must figure out where a story is going – and help hone it.

The externalities of progress. When Rebecca started working in VC, she considered technology an unqualified good. The last decade has taught her that commercial success is more nuanced than that, creating unforeseen consequences. Rebecca believes the tech industry must take accountability for the negative externalities it introduces into the world.

Move slow, and build things. Rebecca thinks a lot about iconic historical structures. Architectural marvels like the Great Wall took centuries to build – but they endure millennia later. This contrasts with tech entrepreneurship, which prizes speed and rapid prototyping. While pace has its place, it’s worth considering how building something durable and iconic is sometimes best done slowly.

Cherishing character. No one impacted Rebecca’s thinking more than her father. Lewis Kaden had a distinguished career as a legal scholar, political advisor, and businessman. Among his advice was this memorable phrase: “Admire talent but cherish character.” While those with extraordinary gifts naturally attract attention, and are deserving of praise, Kaden Senior’s words remind us to appreciate the more profound traits that comprise someone’s character.

Technology as terror and salvation. We stand at a “pivot point,” Rebecca believes. Technological progress since the Industrial Revolution has left us facing environmental catastrophe. But though technology has contributed to the current catastrophe, it may prove the key to alleviating it. Forthcoming breakthroughs – in clean energy, carbon capture, and beyond – could change humanity’s trajectory and save us from the worst.

One Patagonia vest in obsidian plum. One pair of Allbirds Tree Runners in mist. A favorite table at Sightglass Coffee. A favorite run at Northstar, Tahoe. An Apple Watch, an Oura Ring, an intelligent mattress, a thinking fridge, a faintly conscious cappuccino-frother, a Whoop. A sensible haircut, a close shave, a subscription to Superhuman, spare copies of Shoe Dog and Sapiens, a set of Excel shortcuts coded into the dermis.

This is the caricature of a modern venture capitalist. It is an uncharitable depiction and, usually, an inaccurate one. Is anyone quite so anodyne? Could a person really be so one-dimensional? (The short answer: yes, but rarely.) Every industry has its share of uninspired functionaries and beatific conformists. But this ubiquitous shorthand misunderstands the nature of investing in innovation. At its core, venture capital, especially at the early stages, is a creative endeavor. A rigid checklist, a list of rote questions, a clutch of spreadsheet macros – such tools are of limited use in assessing outlier businesses.

What is needed instead? A gift for reading people. For assessing whether the person across from you is, in some way, unreasonable – and deciphering whether that unreasonableness will produce commercial value. A willingness to avoid things. To avoid conferences, stop reading Twitter, and shut one’s ears to all manner of market noise that clouds and works against conviction. An interest in the fringes of things, in the frayed edges of subcultures and movements. And a willingness to embed oneself in them as an anthropologist and find what is fermenting.

Perhaps most important is an understanding of stories. At the earliest stage, that’s all a startup is: a storyteller and a story. It is a tale about the future, told by someone who believes they can see it. The most visionary investors are those able to distinguish between the many fictions that will remain so and those rare cases in which narrative becomes reality.

Rebecca Kaden is someone with a profound appreciation of stories, their shape, and how to hone them. After graduating from Harvard with a degree in English and American Literature, Rebecca worked as an editor at Narrative Magazine, a publisher dedicated to transitioning readers and writers online. It was an early indication of Rebecca’s ability to understand the story in the market and those on the page. While Amazon had launched its e-reader the prior November, for most Americans, kindle was still something you did to a campfire.

An MBA at Stanford bridged Rebecca’s transition from publishing to investing. After working at Maveron for over five years, she joined Union Square Ventures (USV) as a General Partner in 2017. It seems a particularly felicitous fit for a thinker like Rebecca. Not only is USV one of the most consistently successful venture firms in the industry, it’s notable in its approach. It is an explicitly thesis-driven fund that thinks deeply about the future and invests against its vision. In a sense, USV is a storyteller in its own right, crafting a narrative about where the world is headed and seeking entrepreneurs aligned with that view.

In today’s piece, Rebecca shares her appreciation for stories, discusses the narratives of entrepreneurship, and looks ahead at what the future holds.

What would you be doing if you didn’t work in venture?

I have always been fascinated by stories – reading them, hearing them, telling them, understanding how important they are to processing our world and creating our reality. I love thinking about how something can come to life from nothing except the first spark of an idea, whether that’s a story or a company. In college, I thought I’d be a writer or an editor. Then a journalist. In some ways, venture was a sharp left turn but in others, it’s a variation on a theme – threading ideas together and figuring out where to believe what’s currently only a story. The technology ecosystem is about breathing life into figments of imagination and betting on the outside chance they become fixtures of how we live. I love the constant drive towards creating the new, the necessary belief that change is inevitable, and the puzzle of working through hurdles involved. I like that it’s hard and that optimism is a prerequisite. And I really like that the most important part ultimately isn’t the technology or ideas but the people behind them – the characters and their ambitions, strengths, mindsets, and ability to work together. I think in one way or another, I’d be working in this world, if not as an investor, maybe from the other side as a founder, trying to create that story.

Which current or historical figure has most impacted your thinking?

It is likely a stretch to call my Dad, who passed away a few years ago, a historical figure, but no one has had a bigger impact on my thinking. His professional life spanned categories, finding success and fulfillment in the public sector, law, and business, but the common thread throughout his career was his profound judgment. His roles were defined by being the go-to for advice and sound perspective in difficult moments. He was a deep thinker with low ego and quiet confidence. He felt no need to be the loudest voice in the room but was generally the most heard and valued. He was passionate about developing and betting ahead on people. I think a lot about how he taught me to admire talent but cherish character, and, most importantly, to spot the difference between them. I love that he took great pleasure in the career and life he built – far beyond what he would have imagined to be possible – and made himself open to the unexpected turns that would introduce surprising opportunities. I appreciate how he shared his professional successes and challenges with his kids from early ages and showed us what it felt like to have our opinions valued, even about topics well out of our scope.

He also taught me what it looks like to have a thriving, high achieving, and successful career with competing pressures and a commitment to exploring outside interests and giving back to causes he believed in, but also priorities that are crystal clear – for him, his family and, particularly, his children. Professionally, he was known for sound perspective. Personally, he had a wildly blind and unbending belief in his kids. He made us feel like he was fully in it with us, whatever it was, without question. We were an indestructible team. As a parent, I want my kids to feel exactly that.

What is the most significant thing you’ve changed your mind about over the past decade?

Though technology has driven huge improvements to our lives, it is hard to think of it as an unqualified good. That seems difficult to align with my career as a technology investor, but actually, that evolution in perspective has only strengthened my belief in the importance of new transformational products and the importance of innovation. But it has also increased my conviction that it matters deeply where it comes from.

A decade ago, I was only a couple of years into my venture career. I believed that growth and progress were synonymous – in an industry where scale was the ultimate target, platforms that achieved it were glorified. A decade later, I have learned that success is more nuanced, and we have to take accountability for the outcomes we encourage. New dominant platforms can transform how we live but also present challenges: loss of control of our privacy, loneliness, a free-for-all of data control, and increased inequality. These are often unforeseen at the outset. But I’ve also come to believe that predicting the issues is both in our control and our responsibility. Platforms grow toward incentives built in. As we look toward new platform shifts and opportunities for market dominance, I’m thinking a lot more about technology not just creating scale but, with it, creating the world we want to live in. Who owns our digital lives? Where do data control and privacy fit in? How can we fuel belonging and not only connectivity?

Also, olives. I used to hate olives. But, somewhere in the last decade, I gave them a chance and now I find them often the perfect salty snack.

What craft are you spending a lifetime honing?

Seeing the world through others’ eyes. Deep understanding of someone else’s perspective is at the heart of many things I care most about: parenting and marriage, great friendships, building and investing in the next generation of transformative products and technologies, sustaining and evolving a partnership. It is the unlock to challenging biases, bridging divides, and fostering personal growth. And ultimately, it’s the root of real human connection, which is, I think, what brings me the greatest fulfillment.

What do you consider your greatest achievement so far?

Having a challenging and rewarding start to a career while also building a strong and loving family. My sons are two and five, my marriage is seven years old, and I’m only twelve years into this career (out of what I hope will be many decades.) So each part is somewhere between a toddler and a tween – early days. Balancing all the pieces of the puzzle is as challenging as many warned it would be but also far, far more gratifying. I relish in building my family, building my investing career, and building USV. And I constantly learn how each makes me better at the other. The combination has taught me a lot about prioritization, efficiency, and forgiving myself for mistakes that happen along the way, which has always been hard for me to do. It has taught me a lot about identity, which pieces matter to me, and how. It has brought deep camaraderie with others navigating similar journeys and friendships that matter. I’m proud of all of it and of myself for making it happen, chaos and all.

What is your most contrarian, high-conviction opinion?

Despite the increasing polarization of our society during the past decade, it’s still possible for people with different backgrounds, ideologies, and perspectives to find common ground and ways to work together constructively to build a better world. The tribalism and polarity we are currently living in are troubling and problematic. But I don’t think it’s inevitable or irreversible. I believe greatly in the capacity for understanding, compromise, civility, and forward progress – and think small examples of it, particularly from the right leaders, can go a long way in changing course.

What piece of art can you not stop thinking about?

One of my favorite essays, “Goodbye to All That” by Joan Didion in Slouching Toward Bethlehem, starts with a line I think about all the time: “It is easy to see the beginning of things and harder to see the end.” The whole essay is fantastic. Didion is writing about when she just moved to New York City for the first time in her twenties and it’s about that optimism, naivety, hopefulness, and messiness that comes with beginnings, particularly when you’re young. It’s all glittery and confusing. And then it’s also about the inevitability of the fade, which is quieter and subtle. It applies to so many things – chapters of life and trends, companies and the process of building, relationships. I remember first reading it right after college when I, too, had just moved to a new city, and it really hitting home. But like the best stories and essays, it somehow always seems relevant and written for me.

I also think a lot about the old, iconic structures around the world that have stood the test of time and, in many cases, where we aren’t quite sure of all the details of how they were constructed. Marvels like the Colosseum, Roman aqueducts, or the Great Wall. Incredible architectural feats that were, by necessity, built to last and built slowly – slower than we probably could really imagine today. I think because I spend so much time thinking about the new and the fast, I’m also fascinated by what needed to be slow and where that pace paid off in shaping a world those working on it could not have imagined.

What trait do you value most highly in others?

A drive to continuously seek greater understanding. This insatiable curiosity and genuine desire to comprehend the complexities of the world and the people within it is a quality that fosters growth, empathy, and connection. It opens the door for people to move beyond surface-level judgments and assumptions, allowing for richer, more meaningful interactions. I find people who have this more interesting – they are learners and seekers and believe the future state can be different from the present. And they bring an open-mindedness, compassion, and kindness to each other, which I think is the unlock that will bridge the dramatic polarization we’re currently battling.

What are you obsessed with that others rarely talk about?

Lately, I’ve been somewhat obsessed with the idea of “conviction.” It’s such a cool concept because it’s the ultimate combination of heart and mind. As an investor, I do a lot of work to try and understand an opportunity. By the time we’re digging deep with a team building a company, we’ve done work on a thesis that gives us context to believe it to be aligned with our overall thinking. We do work on the business: the model, product, market. We spend time with the team, understanding how they think, how they are likely to build and lead, and why they might be advantaged. But, then, ultimately, we get to this somewhat stark moment of conviction – a decision without certainty but with some level of instinct and belief. The work you’ve done is a big input, but then, I find there’s something else, too. It’s some combination of understanding, excitement, experience, gut, and fear. And this process repeats throughout our lives in every decision – our personal lives, our views on the broader world. I increasingly believe the weighting of those inputs is the important factor. Rely too much on experience and you close yourself off to the new that doesn’t pattern match the old. Rely too much on understanding and you lose a risk tolerance that brings big upside, whether investing or otherwise. Rely too much on gut and you’re shooting in the dark. So somehow, we navigate the balance, hopefully better and better, and that’s our process of improving. I find that fascinating.

I’m also obsessed with adult friendship. We speak a lot about family life and work life but less so the role of friends. We harp on it with kids. Then, as we get older, somehow it falls off the map. But, for me, friendship is an essential leg of the stool. In many ways, it’s a daily heartbeat, adding important perspective, sanity, camaraderie, and extra fun to all else happening in my life. I think it’s playing a much more powerful role, or at least it can, than is often spoken about.

What contemporary practice will our descendants judge us for most?

I think this list is, unfortunately, long.

What we’ve done and permitted to happen to our planet is maybe the most obvious. They will be baffled by the unsustainable use of natural resources and its impact on the only environment we can ever have. They will be confused as to why it took so long to act on the obvious and why change looked too incremental. But, hopefully, they will also marvel at concrete examples of technology offering massive breakthroughs – individual teams dreaming up and creating huge advances in both adaptation and mitigation technologies that were trajectory-changing and saved us from the worst. Carbon capture, new sources of energy, and products that helped people adapt to new ways of living. If future generations are around to take this history lesson, it’ll be one of optimism, thanks to some of the technologies we are seeing emerge.

They’ll judge us for an education system we’ve allowed to become far too expensive, ineffective, and exclusionary in a world where personalized, cost-efficient, and effective learning is abundantly possible. No one will even be able to make sense of the healthcare system we’ve created. And they’ll wonder why we allowed a society so rich and high potential to become bogged down with tribalism, hatred, and fear in those we don’t understand.

What will the next generation do or use that is unimaginable to us today?

Future generations will eradicate most of the diseases that plague us today through a combination of technology, data, and better forms of governance and policy. Cancer, for example, will not be something we die from. Healthcare will be free, and the default will be a proactive and preemptive approach versus treating the sick. Data will transform treatment – large, rich models will dramatically speed up the quality of care and standardize access to it broadly, driving down pricing. Our norm will be to start interactions with a healthcare provider through software powered by large data sets. It will feel like a no-brainer: faster, safer, more accurate, more private, and cheaper than the current mazy diagnostic system. Healthcare will be patient-centric, not system-centric, so each interaction will recall those that came before, no matter what platform it was on or where you were treated. And mental health treatment, thanks to these changes, will be a de-facto assumption, like taking a baby to the pediatrician.

If you had the power to assign a book for everyone on earth to read and understand, which book would you choose?

Pale Fire by Vladimir Nabokov. It’s a wild, unusual book by an unusual person and author. It’s structured as a fictional 999-line poem and then a fictional line-by-line annotation of it. It requires a lot of choices at every turn – including how to read it (the poem and then the annotation? Flipping back and forth?). So it makes you work for it. But at heart, it’s an incredible work about the relevance of stories, how thin the line is between our reality and the narratives we tell ourselves, and the importance of those narratives for sustenance. It’s also about imagination and creation and that whole worlds can be created by powerful ideas. It asks the reader to constantly figure out what is real and what is not, or to give up and accept the uncomfortable state of not knowing, thereby embracing the story. I love reading across genres, but nothing deepens my thinking and takes my mind to new places like great works of fiction.

How will future historians describe our current era?

The increasing democratization of information alongside growing economic inequality.

The pivot point between a society too divided to prioritize what matters and preserve the world for future generations and one deeply rich with imagination, progress, and technological innovation that had the ability to change course at the most meaningful moment.

Liked this piece? Check out a few of our previous interviews:

Modern Meditations: Reid Hoffman

Modern Meditations: Claire Hughes Johnson

The Generalist’s work is provided for informational purposes only and should not be construed as legal, business, investment, or tax advice. You should always do your own research and consult advisors on these subjects. Our work may feature entities in which Generalist Capital, LLC or the author has invested.

See important disclosures at masterworks.com/cd