🌟 Hey there! This is a subscriber-only edition of our premium newsletter designed to make you a better investor, founder, and technologist. Members get access to the strategies, tactics, and wisdom of exceptional investors and founders. Become a member today.

Friends,

In all of venture capital’s rush to enter investments – to find and jockey and win – it can be easy to forget that you must exit them, too. No matter how long-term your vision, how persevering your commitment to founders, there is a moment when you must part ways and cash out. It is not just a part of the game; it is the point of the game.

Yet, it is rarely discussed. In part, that’s a consequence of venture capital’s time horizon. Ten years is a long time, especially when managers face more pressing problems daily. Another is that exits have historically depended almost entirely on external forces – an IPO or an acquisition. Save for the asset class’s greatest powerbrokers (who can broker alliances and arrange marriages), exits are often perceived as something to be experienced rather than created. You play the cards you are dealt and sit at the felt table until someone else carries your chips to the cashier’s cage.

This vision of venture capital no longer holds. Market and regulatory shifts have altered the category’s complexion and made it more possible – and more vital – for investors to forge exits for themselves through secondary transactions and crypto sales. Both have become essential parts of the savvy VC’s toolkit: mitigating startups’ increasing long lives as private companies and pulling forward returns for LPs.

Understanding how to manage this is now a crucial part of the venture capital craft.

Otherwise

Secondaries are a growing trend. Are we going to be talking about them more or less in the next 5-10 years? Much more. Fund managers need to be aware that this is becoming increasingly common.

– Terrence Rohan

The opacity and complexity of secondary transactions – who they involve and how they occur – make them tricky subjects for investors to master and use to their advantage. Many give them little thought until an opportunity arises. Foresight and planning can make a significant difference.

To deliver that foresight to readers, we’ve spent months researching the space and interviewing a dozen investors with experience buying and selling secondaries. Today’s guide unpacks how these transactions occur, the major players, and the frameworks elite VCs use to time and size their exits.

What to expect

A 9,000+ word breakdown on winning with secondaries

How elite investors size their sales and why

The four reasons to consider selling in the secondary markets

The different transaction types managers encounter

How to manage the process with founders to ensure buy-in

How crypto allows for early liquidity

You can unlock the full guide, and the rest of our premium membership for just $22/month.

Brought to you by Mercury

You can’t look into a crystal ball to gauge a company’s future performance — but you can get clarity with a financial forecast. Building a financial forecast model can give you a picture of a company’s viability and help with fundraising and future decision-making. Mercury’s VP of Finance, Dan Kang, shares why and how to build a financial forecast model, along with his personal template.

Table of contents

1. The rise of secondaries

Market shifts

Regulatory shifts

Competitive shifts

2. The buying landscape

Dedicated firms

Traditional firms

Digital exchanges

3. Transaction types

Who leads?

Strip sales

Continuation funds

Token sales

4. When to sell

You’ve hit your target

It’s a big position

Your fund is winding down

Your LPs want liquidity

The market has greater conviction than you do

5. How to win

Build a framework

Size thoughtfully

Understand price dynamics

Work with founders

1: The rise of secondaries

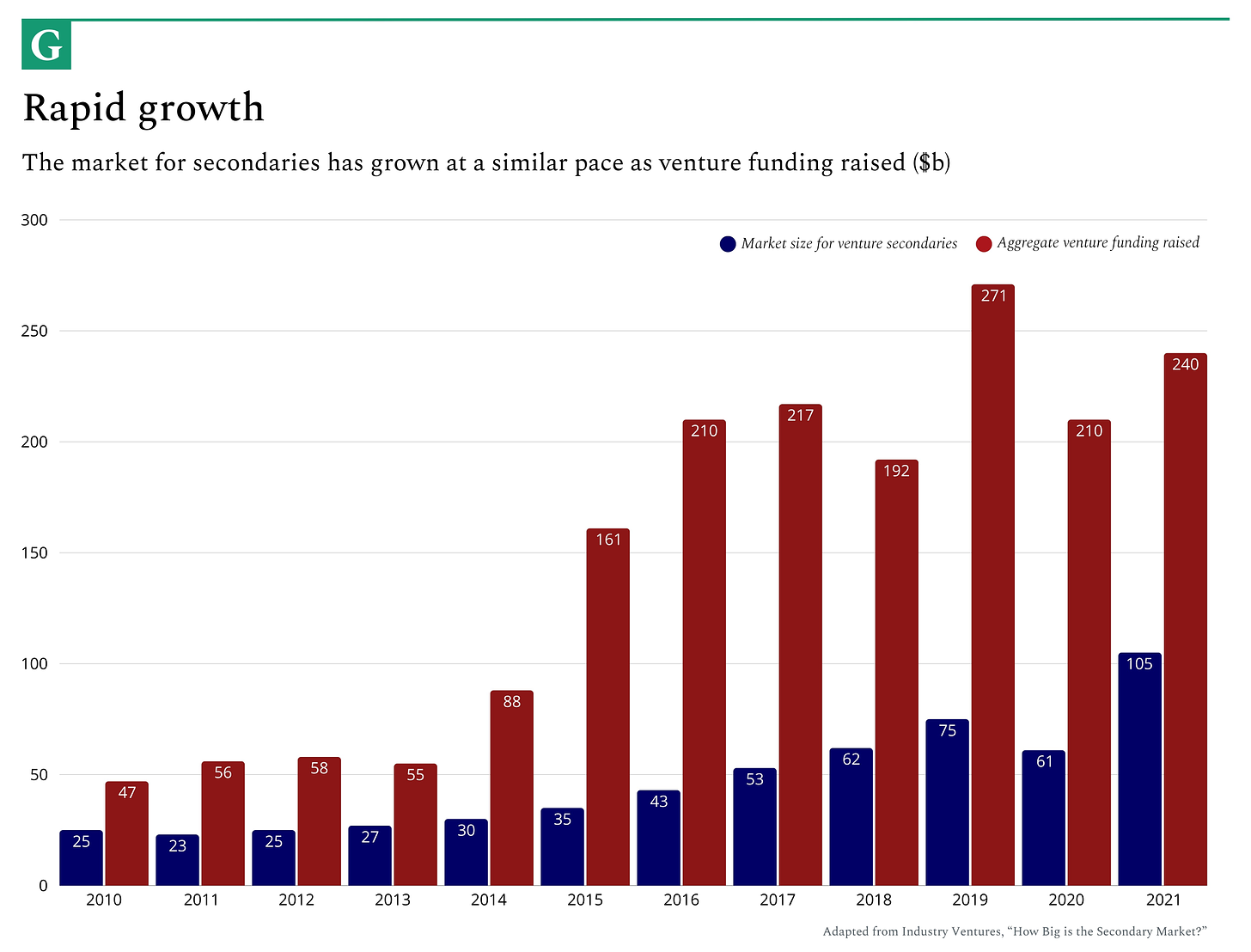

According to Industry Ventures, the global addressable market for secondary transactions in venture was $25 billion in 2012. A decade later, it had hit $105 billion – a 4.2x increase. That quantifies just how rapidly this part of the venture asset class has grown and illustrates the scale of the opportunity for both buyers and sellers.

Market shifts

Market changes have been a critical part of this increase. Between 2012 and 2021, annual capital raised by venture funds grew from $58 billion to $240 billion, approximately a 4.1x jump. With larger coffers, venture firms have been able to capitalize startups at greater rates for longer, extending their stints as private businesses and delaying public market debuts.

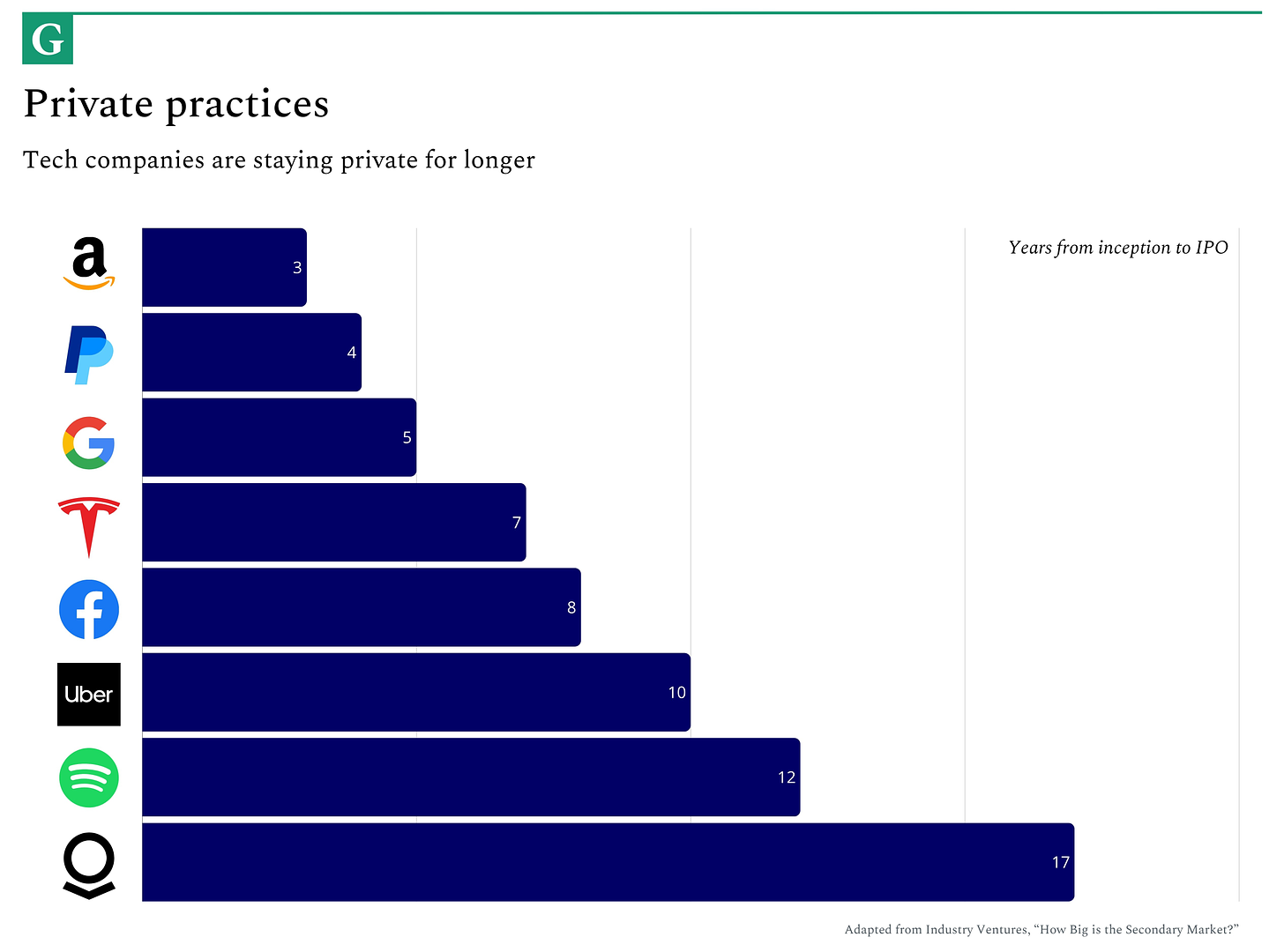

Today, it’s common for a startup to spend over a decade as a private business.

Stripe is 14 years old and Palantir made its IPO at 17. SpaceX is the same age as The Wire, Eminem’s “Lose Yourself,” and the circulation of the Euro – all products of 2002. Giants of the past took a much shorter route to an exit, as Forerunner’s Kirsten Green remarked:

Forerunner

If you go back two decades ago, Amazon was, what, 18 months or 24 months when it went public? That’s not happening now.

You’ve got to be a multibillion-dollar company to have a fighting chance in the public market. For most companies, that means hitting hundreds of millions in revenue. That is not happening overnight. I do not care how crazy or exciting people think Silicon Valley is. You’re thinking a decade-plus.

– Kirsten Green

Amazon, Google, Adobe, Apple, Salesforce, PayPal, and Tesla are all examples of startups that reached the public markets in five years or less.

They entered as much less mature businesses with lower annual revenues. According to Industry Ventures, the average company that went public in 1989 was 6 years old and had $30 million in revenue; by 2021, businesses were 12 years old and had $200 million in revenue.

CRV

Sequoia used to famously say that if you had invested in all of their companies at their IPOs, you would have made more money than if you had invested in all of their funds. What they didn’t say is that many of their biggest hits went public within three or four years of investing – most of the company building happened as public companies.

– Saar Gur

Though the outcomes are larger today, previous generations’ timelines mapped much better to venture capital. Traditionally, funds have 10-year lifespans; the first five are used to deploy capital, and the last five to reap the returns.

CRV

CRV has 19 funds. Historically, most of our winning companies went public in a relatively short time frame – within the life cycle of a fund, give or take a couple of years.

As a result, there was just less secondary activity throughout our history. The idea that there would be these multi-hundred million dollar transactions didn’t exist until a few years ago.

– Saar Gur

Startups’ desire to celebrate their quinceañera in the private markets has forced VCs to look for liquidity elsewhere.

Acrew

Obviously, companies are staying private longer. We want to provide some liquidity back to our LPs, particularly for companies we think will take longer to achieve a full-blown outcome.

– Lauren Kolodny

As Mike Jung explains, the asset class seizes without funds returning to LPs – many of whom are overexposed to venture.

Founders Circle

In 2022, venture had $50 billion of net outflows from LPs to GPs. That means LPs had to write $50 billion in checks, net of distributions.

It gets to a point where, if distributions aren’t returning to LPs, it’s like having no oil in your engine – it seizes the market. Today, we’re seeing more venture investors for different ways they might be able to sell to later-stage folks.

– Mike Jung

Although market changes have played the biggest role in the rise of secondaries, regulations have also had an influence.

Regulatory shifts

The SEC’s “500 Shareholders Threshold” required companies with more than 499 investors to follow reporting requirements similar to those of public companies, pushing startups into faster IPOs. When the rule was relaxed in 2012, allowing 2,000 shareholders, a forcing function was removed.

CRV

The SEC used to have a rule that if you had over 500 external shareholders, you had to go public. If you look at the history of Silicon Valley, many high-growth startups historically went public within a few years of hyper-growth.

In 2004, I was part of a company called Attractive, and we were getting pressured to go public because of these shareholder rules, even though there was no world in which we should have.

Facebook famously lobbied to change the 500 Shareholders rule so it could stay private longer.

Once that rule changed, venture capital did too. It created stories like SpaceX, Palantir, and Stripe – companies that could be around for 12, 14, or 15 years and trade at tens of billions of dollars in value before going public.

– Saar Gur

Competitive shifts

Competitive dynamics and cultural norms have also contributed. As tech has grown, the war on talent has intensified. To stop Big Tech from poaching their employees with bumper pay packages, startups have looked to mitigate their longer paths to liquidity through secondary sales.

Founders Circle

For several reasons, the broader venture ecosystem has become much more accepting of secondary liquidity.

Take a company that’s doing extremely well and is ten years old. If you were a Series A engineering hire, maybe you were 25 when you joined. A decade later, the company still hasn’t gone public. You’re 35, might have a kid or two, and most of your wealth is tied up in a private company’s stock. That gets difficult, especially when you have big incumbent players like Amazon, Google, and Facebook offering very rich packages to recruit people.

Companies have had to figure out how to help employees understand the value of their shares. You started to see the advent of these tender offer processes when companies reached scale, where everybody could participate in selling their shares to some degree. That’s become increasingly commonplace.

– Mike Jung

Whatever the precise causes behind the rise in secondaries, the result is the same: every thinking investor must recognize it as part of their craft. It is your job to drive returns for investors, and as the landscape changes, that necessitates different approaches and strategies.

USV

There’s an underweighted importance placed on the liquidity element of venture. It’s a skill in itself. Getting into great investments is super hard and is the most important thing, of course. But part of the job is understanding how to manage a fund. How do you that across different macro cycles so your fund makes money?

– Rebecca Kaden