Starbucks, a Tech Company

Howard Schultz reformed the coffee chain by turning it into a tech company.

A man took a sip of coffee, and began to speak.

So, what can I do for you?

Salesforce CEO Marc Benioff, a hulking six-foot-two, skewered a piece of cantaloupe and brought it to his lips. He was supposed to be on vacation. After all, that’s why he came to Hawaii in the first place.

But he’d gotten a call.

They day before, on December 23rd, 2007, his friend Michael Dell rang and asked him for a favor: would he speak to Howard Schultz? Yes, that Howard Schultz. He was in Hawaii, too. And he needed help.

It had been a rough few years for the former Starbucks CEO. Since Jim Donald had taken over in 2005, Schultz had noticed a decline in the company’s service that was only now showing up in the numbers. With Starbucks heading towards financial free-fall, Schultz had decided he needed to take back control. But he knew he couldn’t run the same playbook that had grown Starbucks from a small Seattle roaster into a global phenomenon. The world had changed too much. He would need to embrace technology.

During a bike ride along the coast of Hawaii’s Big Island, Schultz confided in Dell, and asked for his advice. After all, Dell himself had just returned as CEO of his company after three years away.

I’ve got an idea, Dell told him. You need to talk to Marc.

Benioff had proven pivotal in Dell’s return, advising the creation of a new web platform designed to solicit customer feedback and suggestions. That might not have sounded like much, but Dell assured Schultz it had made a big impact, bringing Dell Technologies closer to its customers and inspiring a more responsive organization.

So, on the morning of Christmas Eve, Schultz sat down to breakfast with Benioff, and answered the bear of a man’s question.

I want you to help me make a website. Just like the one you did for Michael.

Just months later, in early 2008, Schultz took the wraps off of “My Starbucks Idea,” a digital suggestion box. Benioff had been a vital advisor on the project.

The creation of My Starbucks Idea represented a turning point in Starbucks’s story, a division between one era and the next. If mastery over the physical domain defined Schultz’s first act, his second succeeded by conquering the digital.

Today, Starbucks is a tech company. Other businesses may boast better coffee, tastier food, or more modern ambiances, but none can currently compete with Starbucks’ app, AI engine, or financial features. These sophisticated capabilities arose from the humble roots of that digital suggestion box, the product of a breakfast between two titans of industry.

Starbucks’ technological lead may not last, however. The last four years have seen an infestation of small-format stores sweep Asia, leveraging tech to increase throughput and improve ROI. Meanwhile, robot-operated kiosks have captured the imagination domestically, and gesture towards an even more automated future. To stay ahead, Starbucks will need to reinvent itself yet again.

In today’s piece, we’ll explore:

Starbucks’ evolution from hipster roaster to mainstream sensation

Whether Starbucks is a consumer app, AI platform, or neobank

The chain’s (small) future

The next frontiers of coffee

Short: Seattle to the World

“Starbo”

The Cascades hug America’s Western Coast. Stretching from the Canadian province of British Columbia down to California, the mountain range epitomizes the stark, lucid beauty that makes the continent’s Northwest such a poetic place to live.

Dotting the Cascade range, buried between Mount Shasta and Mount Baker, is the town of Starbo. A humble mining community, Starbo is hard to find on a map, though it’s easy to imagine the wild beauty surrounding it.

That wasn’t why Gordon Bowker liked the name, though. Co-owner of an advertising agency, Bowker had been convinced by his partner that words beginning with “St” possessed a peculiar, evocative strength. And if he and his old college buddies Jerry Baldwin and Zev Siegl were going to make this whole coffee roaster thing real, they needed a good name.

The trio had discovered the pinprick of Starbo poring over an old mining map, considering it an instant upgrade over their previous front-runner, “Cargo House.” Still, it wasn’t quite right, the men thought, though that discomfort didn’t last long.

Almost immediately, Bowker made the phonic leap from “Starbo” to “Starbucks,” the name of the first mate in Moby Dick.

The character had no connection to the company’s mission, but Baldwin and Siegl liked it, too. The Starbucks Coffee Company was born.

It fitted that the naming process that led to “Starbucks” was so haphazard; at first blush, the backgrounds of its founders were equally devoid of logic. What business did a history teacher, an English teacher, and ad man have starting a coffee roaster?

But ever since the University of San Francisco alums had learned how to roast beans from the high-priest of coffee himself, Alfred Peet, they could think of little else. With his blessing, they opened Starbucks, intending to use the Dutch immigrant’s techniques to bring high-quality coffee up the coast. (For the first year of operations, Starbucks bought beans from Peet’s Coffee.)

On March 30, 1971, Starbucks opened its first store at 2000 Western Avenue, along Seattle’s waterfront. It bore little resemblance to the living-room lounges the company would later popularize. Starbucks was not a coffee company; it was a coffee bean company.

It might have stayed that way had Bowker and Co. not met a young man from Brooklyn.

La Vita Bella

The same year that Starbucks was founded, Howard Schultz graduated high school. He’d grown up in Canarsie’s housing projects, the son of a truck driver.

Hoping to walk on to the football team, Schultz attended North Michigan University, leaving with a degree in communications, but no appearances for the Wildcats.

After school, Schultz began a career in sales, first at Xerox, then at Hammarplast, a maker of coffee machines and other appliances. The company sent Schultz to Seattle in 1981, to fill orders for coffee filters. It was on that trip that the eager salesman visited a little roaster along the Seattle shoreline: Starbucks.

Impressed by the quality of the craftsmanship and sensing opportunity, Schultz decided this was where he wanted to work. Within a year, he’d left Hammarplast to become Starbucks’s “director of retail operations and marketing.”

Only in 1983 did Schultz’s vision for the future of coffee materialize.

Like so many before him, Schultz took a trip to Italy and fell in love with the country’s culture. As you might expect, he particularly marveled at the quality of the espresso, and even more importantly, found himself captivated by the “romance” that illuminated Milan’s coffee bars.

This is how coffee should be enjoyed, he thought. This is what Starbucks needed to become.

He returned to Seattle fizzing with inspiration. But when he tried to convince Bowker and the team to turn Starbucks into an Italian-style cafe, he was rebuffed.

No, the founders told him. Starbucks was a roaster and always would be.

It was time for Schultz to go solo.

The Ahab of Starbucks

From 1985 to 1988, Schultz and Starbucks progressed along separate paths.

With a $150,000 investment from Bowker and further seed capital from local investors (he pitched over 240), Schultz launched Il Giornale, the coffee house of his dreams. Along with generous seating, Il Giornale sold gelato and piped opera through its speakers, creating an atmosphere meant to encourage customers to stay.

It seemed to work.

Il Giornale added a second store in Seattle, then one in Vancouver. Soon there were five delightful cafes, bringing a touch of Italian elegance to America’s Northwest.

In a parallel universe, perhaps Il Giornale stores freckle the globe, and Starbucks remains an esoteric local roaster. Schultz certainly started the brand with big ambitions, as shown in an early memo he wrote to employees:

Il Giornale will strive to be the best coffee bar company on earth. We will offer superior coffee and related products that will help our customers start and continue their work day...Our coffee bars will change the way people perceive the beverage.

But back in our dimension, in the Year 1987, a unique opportunity presented itself: Starbucks went up for sale.

The three founders were ready for a new adventure. They’d bought Peet’s Coffee in 1984 and were now prepared to relocate to San Francisco to run the company for which they had such respect. Knowing Schultz’s passion, the founders offered their former protege first dibs: if he could drum up $3.8 million in 60 days, the company, name included, was his.

There was only one problem: Schultz was broke. He’d poured his money into building Il Giornale and reinvested to maintain growth. While he’d built a solid reputation, he’d still only been operating for a little over a year. Raising that much money would be tough.

As Schultz tells it, only thanks to an “angel” did he succeed in his takeover. After 30 days, one of Starbucks’ founders contacted Schultz to see how he was doing and deliver some bad news: Starbucks had received an unsolicited bid for $4 million. Worse yet, the offer had come from one of Il Giornale’s angel investors.

First stunned, then hopeless, Schultz saw his dream slipping away. He recounted his woes to a lawyer friend one evening, who served as the conduit for Schultz’s salvation.

Maybe I can help, the friend said. Come by the firm tomorrow, and I’ll introduce you to the founding partner.

Bill Gates Senior was a titan of a man.

Six foot eight on a good day, the father of Microsoft’s tycoon was also the architect of one of Seattle’s most prestigious firms, Shidler McBroom & Gates.

The next day, Schultz found himself sitting in front of the giant, telling his story. After he’d finished, Gates Sr. asked him two questions:

Is everything you told me true?

Yes, Schultz responded.

Have you left anything out?

No, I haven’t left anything out, Schultz assured him.

Ok. Come back in two hours.

With his heart in his throat, Schultz waited at a nearby coffee shop until the necessary time had passed. When he returned, Gates Sr. said, simply, We’re going to see the man.

Just a few minutes later, Gates loomed over the desk of the investor that had threatened to snipe Schultz’s deal.

You should be ashamed of yourself. You are going to stand down, and this kid is going to realize his dream. Do you understand me?

He did.

Back outside in the crisp Seattle air, Gates uttered the words that brought that dream to life:

You’re going to buy the company, and my son and I are going to help you.

Schultz summarized the episode decades later, emphasizing just how important Gates had been.

Bill Gates saved me, saved Starbucks, was a mentor and an angel with great humility and never told a soul how he helped me.

Schultz was finally captain of the good ship Starbucks.

A store on every corner

What followed over the next decade and a half was one of the most virtuosic executive performances of the last century.

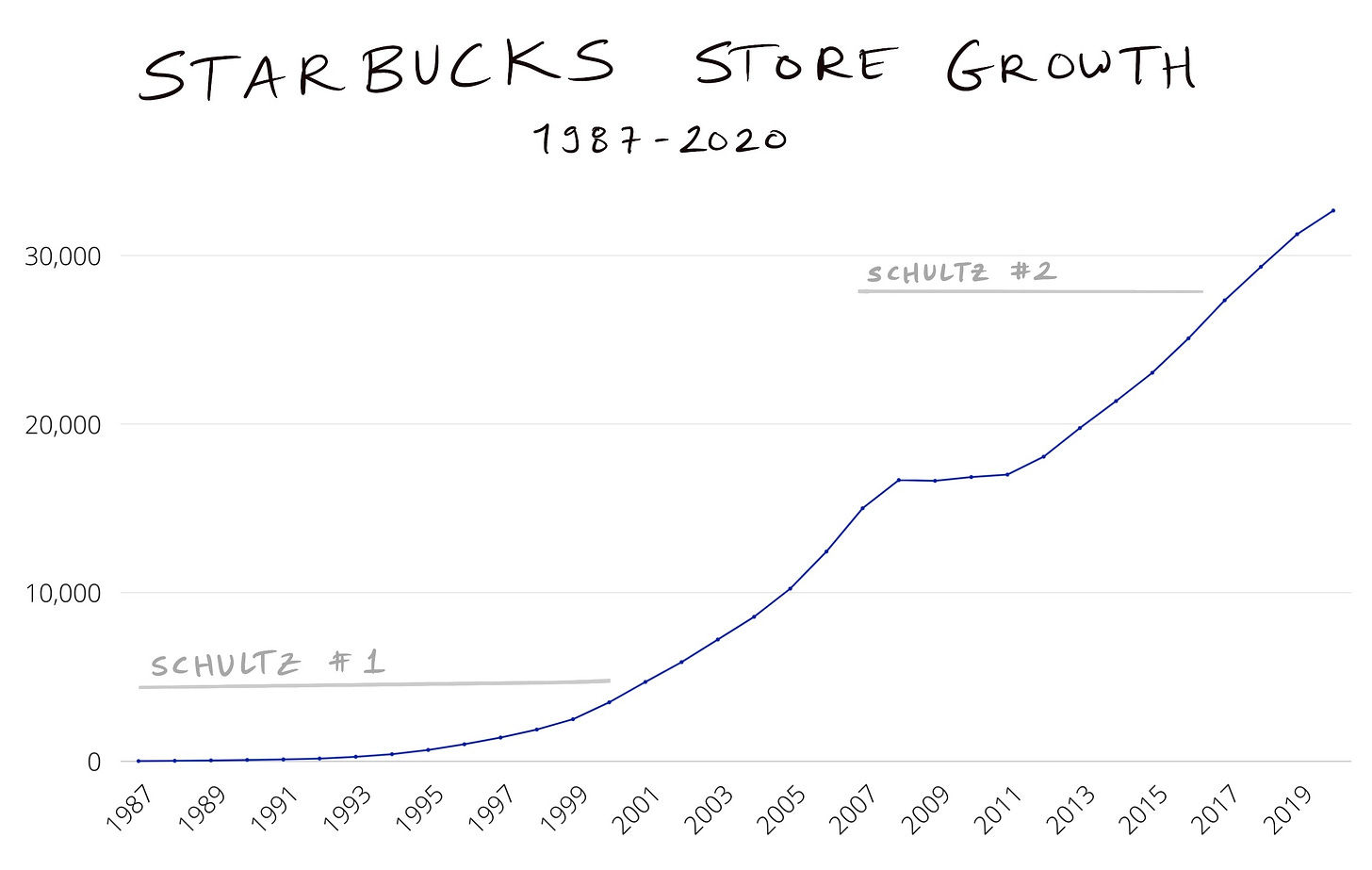

Combined with his newly rebranded Il Giornale stores, Schultz began his tenure as CEO of Starbucks with control of 11 locations. Soon, he was managing 17. By the end of 2000, he would oversee more than 3,500.

That hyper-scale was achieved through a combination of strong customer demand, impressive service, aggressive reinvestment, and shrewd licensing deals.

There’s no doubt that Starbucks benefited from unusually robust product-market fit. Trapped in the low-quality doldrums of Folgers for the last 130 years, America was ready for a higher-caliber cup of joe. This desire coincided with a new curiosity in imported specialty foods (like Starbucks’s arabica beans) and higher per capita income. With the 1980s, and to a lesser extent, the 1990s, defined by excess and conspicuous consumption, a frothy latte represented an affordable luxury that many could enjoy every day.

Under Schultz’s leadership, Starbucks compounded that demand by focusing on exceptional, sincere service. The ethos of genuine care for customers began at the top with Schultz’s treatment of staff. Rather than “employees,” Starbucks had “partners.” That represented more than just a flattering title — nearly everyone in the company, including baristas and store managers, had a share in Starbucks’s success and received benefits like health insurance and educational support. That trickled down to customer interactions with happier, better-supported partners taking extra care to learn locals’ names and remember favorite orders. Schultz cared about every tiny detail of the Starbucks experience, from the “theater” of crafting a beverage to the decor of the stores.

Remarkably, Schultz was able to preserve these essential qualities even as Starbucks took over the world. He primarily financed this growth from the public markets — “SBUX” hit the Nasdaq in 1992 at a share price of $17; a $10K investment at the time would now be worth $4.3 million.

In terms of M&A, Schultz sought to either expand Starbucks’s product line (and subsequently AOV and LTV) or footprint; ideally both. Key pickups included:

1994, The Coffee Connection for $23 million. The 24-store chain was popular in the New England area, not least for its icy treat, the “Frappucino.” The buy insured Starbucks got a strong foothold in the Northeast while adding a popular drink to the menu. By 1996, Starbucks sold $52 million worth of Frappucinos.

1998, The Seattle Coffee Company for $83 million. Despite its name, The Seattle Coffee Company was based in the UK and ran 56 stores. The purchase made Starbucks an overnight player in the country.

1999, Tazo Tea for $8.1 million. Starbucks sold Tazo’s products in its stores and experimented with opening standalone Tazo shops. After acquiring Teavana in 2012, Starbucks shifted focus to the new brand and sold Tazo to Unilever for $384 million. Not a bad profit.

Licensing represented another strategy. Ex cathedra, Schultz was against franchising, unwilling to relinquish control to other parties. But to access specific locations (college campuses, airports), channels (grocery), or geographies, licensing was necessary. Starbucks typically had a minimal role in the operations of these locations and earned a fraction of revenue.

Fittingly, Starbucks’s first licensed store was in Seattle’s Sea-Tac airport. Its first partner to distribute pre-made drinks in supermarkets was Kraft Foods.

By the time Schultz stepped down in 2000, Starbucks was earning more than $2 billion in net revenue and was sold around the world, from China to Australia to Qatar to South Korea to the United Kingdom.

Reclaiming the throne

And so we return to breakfast and Benioff.

If Schultz’s rookie run was exceptional, his comeback was arguably even more so given the challenges Starbucks faced. While predecessor Jim Donald had continued scaling stores and revenue, a loss of operational control eventually manifested in the company’s financials. In Schultz’s first quarter back at the helm in 2008, Starbucks grew revenue by just 1.5%. The year before, the company had logged growth of 20.4%.

Operational deterioration was just one of the issues Schultz had to face. If the ‘80s and ‘90s seemed part of a conspiracy to vault the coffee company into the stratosphere, 2008 appeared dark karmic retribution for an unknown crime. Among Starbuck’s significant problems:

A looming global financial crisis. As the banking sector collapsed, consumer discretionary income thinned, making the purchase of a latte seem less like an earned treat and more like an unsustainable decadence.

Competition from above and below. When Starbucks entered the market, Schultz could, with a straight face, declare the company made the best coffee in the country. As Starbucks went mainstream, local rivals chipped away at the top-end of the market. Meanwhile, Dunkin’ and McDonalds began capturing the bottom with cheaper products.

A less desirable product. A Consumer Reports taste test in 2007 pitted Starbucks against McDonald’s and Dunkin’. McDonald’s won. Starbucks’s uber-bold roast was losing popularity.

Worse atmosphere and service. New coffee machines blocked the “theater” of creation that Schultz held so dear. Worse, inadequate training often meant that baristas and managers neglected the little things like remembering a customer’s name.

To surmount these challenges, Schultz realized he would have to think differently. One morning, before Starbuck’s historic Pike Place opened, Schultz stood in the dark and made himself a promise. He would not blame anyone for Starbuck’s recent failures. Instead, he would take responsibility and rebuild Starbucks not by looking backward, but by looking ahead.

Reinvention

Starbucks’s recovery relied on getting back to basics, accelerating expansion in China and India, and embracing technology. This final point is arguably most profound today, with three key initiatives highlighting how tech came to Starbucks. With My Starbucks Idea (MSI), Starbucks Rewards, and VIA, the global brand exhibited diverse technical capabilities, a customer-driven ethos, and long-term thinking.

As trivial as it sounds, MSI was critical to the turnaround.

Over the eight years spanning Schultz’s second spell, MSI delivered a steady stream of inspiration while also bringing back some of the consumer love that had been squandered. Many improvements suggested on MSI are synonymous with Starbucks today:

Free Wifi in stores.

Free birthday treats.

No receipts for purchases under $25 to save paper.

Online gifting of beverages between friends.

The “skinny” mocha.

Offering sugar-free syrups.

Collaborating with Keurig to create K-Cups.

Sell cake pops.

Introduce a rewards system.

This final idea proved vital. Though the company had sold gift cards since 2001, a more holistic loyalty system was a consistent refrain on MSI. Introduced in 2008, Starbucks Rewards “exploded” once available in the form of a mobile app the following year. Soon, millions of customers had joined the program, and hundreds of millions of dollars were being loaded onto Starbucks Rewards cards.

The success with MSI set the stage for another kind of digital communion: social media. Starting in 2008, Schultz pushed his deputies to execute an aggressive social strategy on Facebook and Twitter. Within months, the company had accumulated 1 million Facebook fans, a figure that would jump to 27 million by 2010. According to Altimeter, in less than a year, Starbucks went from social n00bs to the most “deeply engag[ing]” brand.

Starbucks also brought a significant food technology project to fruition. In 1993, Schultz had hired a cellular biologist obsessed with creating a high-quality instant coffee. Sixteen years later, Starbucks VIA — a water-soluble instant coffee — launched in the United States. In just ten months, VIA grossed $100 million in revenue.

Of course, Schultz also addressed the company’s issues outside the digital realm. That included shaking up the executive team, closing down underperforming stores, and retraining the entire Starbucks staff. The CEO also bolstered the product line through acquisitions (La Boulange, Evolution Juice, and Teavana, chief among them), better penetrated CPG channels, and grew footprint in Asia.

None of these amendments should be overlooked, but all were essentially evolutions, improvements on existing processes. The most significant change was undoubtedly spawned along the coast of Kailua-Kona. Schultz had returned as CEO of a coffee business. He left as CEO of a tech company.

Tall: Starbucks, a tech company

It would be reasonable at this point to be thinking, C’mon, now. Is Starbucks really a tech company?

You’re right that if you asked 100 people what Starbucks does, precisely zero of them would say “AI upselling” or “consumer fintech.”

Allow me to make my case.

Yes, Starbucks sells coffee. That is how it makes its money and were it to stop doing that, the company would cease to exist. Fin.

However, all of the most exciting ways the business seeks to differentiate itself rely on technology. As the coffee sector grows more competitive, pixels and bits will influence buying decisions and open new revenue channels more than the harmony of a specific blend.

Heck, even their CEO is a tech guy: Schultz’s successor, Kevin Johnson, began his career as a developer at IBM, became VP of worldwide sales at Microsoft, and subsequently served as CEO of Juniper Networks, a publicly-traded enterprise software and networking business.

So, Starbucks is a tech company. (At least, to some degree). But what type of tech company is it?

It’s three-in-one: a high-engagement consumer app, an AI platform, and a neobank.

Consumer app

If the law permits, selling a high-margin addictive substance makes for a tidy business. Coffee is just such a miracle substance: legally pristine, largely stigma-free, consumed at least once daily, available in neverending forms and formats, cheap to produce, easy to sell, and habit-forming. Jackpot.

It’s perhaps unsurprising that an app that secures this matitudinal narcotic is similarly well-frequented. That proves to be true of Starbuck’s mobile app.

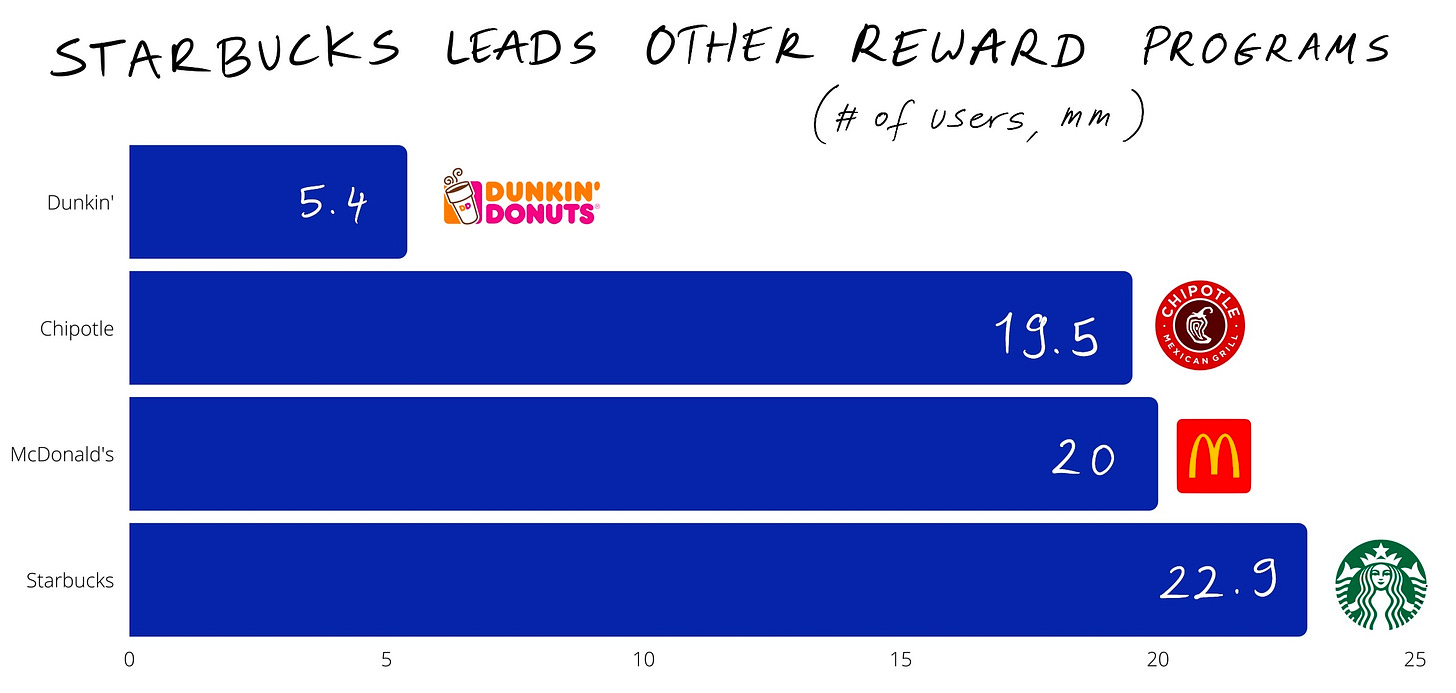

Though simple in function — offering a sleekly designed place to order ahead, earn rewards, and gift drinks — it has proven popular. In the most recent earnings call, Johnson noted that 52% of domestic sales came from Starbucks Rewards members, with mobile orders making up 26%. Starbucks reported 22.9 million “active” Rewards members, an increase of 1 million over the past quarter. During the pandemic, the company picked up 3.5 million members. This has been boosted by the “Stars for Everyone” initiative, which grants anyone who uses the app — even if they don’t preload money — “stars,” which can be redeemed for rewards. Previously, stars were only available to Rewards members that preloaded funds. (There’s some nuance here, which we’ll discuss below.)

That seems to compare favorably with peers, though differing definitions around what constitutes an “active” user make direct comparison difficult. McDonald’s professes to have 20 million active app users, Chipotle claims 19.5 million, and Dunkin’ Donuts lags at 5.4 million.

The scale of Starbucks’ digital user base, and the speed of growth, are both impressive.

The benefits of online ordering extend beyond having a direct, omnipresent customer relationship, impacting operations. When customers order ahead, Starbucks partners are better able to triage production and use free time to delight customers.

Of course, much of the app’s power is down to its ability to influence consumer behavior. For that, Starbucks relies on its secret weapon: Deep Brew.

AI platform

Drip coffee in the morning (+ Southwest Veggie Wrap + Avocado Spread).

Discounted Caramel Frappuccino in the afternoon (+ Marshmallow Dream Bar).

Reward Mint Tranquility tea on the way home (+ bag of Blonde Roast).

This is the dream Starbucks consumer schedule: a finely-tuned, highly personalized string of discounts, upsells, rewards, and expansions.

In its quest to maximize AOV, increase the frequency of customer visits, and optimize throughput, Starbucks relies on a superabundance of data from consumers and the business itself. Its sophisticated AI capabilities parse that information to inform its suggestions. A few examples of how this plays out.

Geographical information. You’re close to home, and it’s 11 am on Saturday. Starbucks uses this information to suggest you get a danish as a weekend treat.

Contextual information. It’s Tuesday, and it’s raining. To coax you out of your office, Starbucks offers a discount on one of its specialty beverages.

Purchase history. You order an almond cappuccino every morning. To bump up AOV, Starbucks suggests you try out the almond croissant or fruit and nut snack.

Interaction history. Because you always order hot drinks, you haven’t explored the “Cold Beverages” part of the menu. Starbucks offers a discount on the Nitro Latte to encourage you to broaden your base.

Store capacity. It’s 9 am on a Monday, and your local store is at maximum capacity. To manage throughput, Starbucks encourages you to get an Americano, which requires much less time to make than a latte.

This is not a fantasy but the impressive reality of Starbucks’ AI abilities.

Increasingly, this level of personalization is managed by Deep Brew, a semi-omniscient AI platform.

Unlike its predecessors, Deep Brew represents a unified system that drives decision-making across the entire organization. Not only does it nudge users to buy a particular type of latte, it influences employee staffing schedules, inventory levels, machine maintenance (thanks to IoT connections), and store expansion. Even more than many tech companies, Starbucks runs itself like a piece of software.

Managing expansion has proven particularly crucial this past year as the company responds to the pandemic. Deep Brew has led the charge in benchmarking how different markets might recover. From Johnson:

We're now using our Deep Brew AI technology to start to monitor and look at the vaccination progress of every country around the world and use predictive analytics to give us a view and correlation to how that's going to pace the recovery and the acceleration of our growth in International business.

Though almost every company is keen to tout its AI and big data capabilities, Starbucks has every reason to be genuinely proud. It has built arguably the most advanced system in its space, and given its extensive reach, has every opportunity to improve through further usage.

Neobank

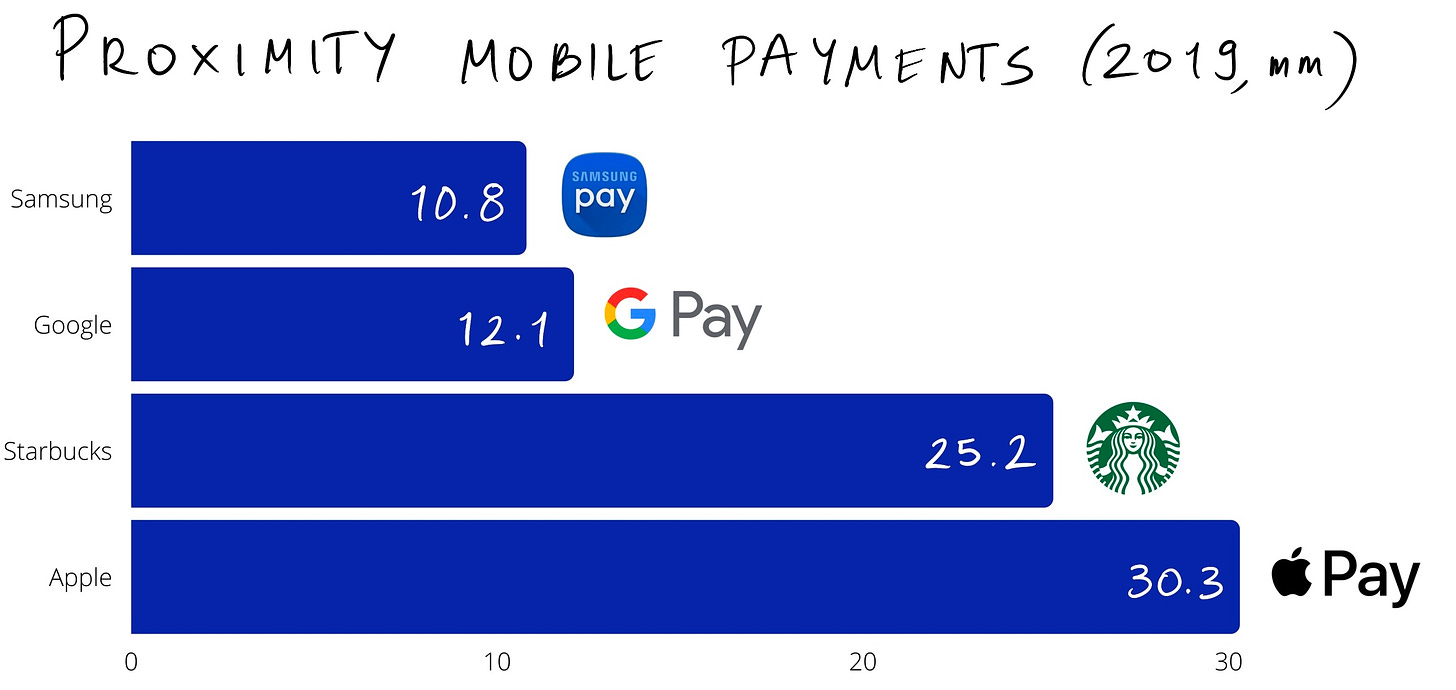

A startling statistic did the rounds in 2018. By number of users, Starbucks was the most popular location-based mobile payment app in the US.

With 23.4 million users (a higher figure for definitional reasons) paying with the app at least every six months, plucky Starbucks beat out Apple Pay (22 million), Google Pay (11.1 million), and Samsung Pay (9.9 million). This was remarkable. By definition, Starbucks’ mobile payment could only be used in the company’s stores, whereas alternatives like Apple Pay were available across retailers.

Apple (30.3 million) has since overhauled the coffee chain according to the same customer intelligence platform’s most recent figures, but Starbucks (25.2 million) still far outstrips Google (12.1 million) and Samsung (10.8 million).

Mobile payments are just one reason Starbucks might be considered a fintech company, and more precisely, a neobank. In addition to facilitating purchases, Starbucks also stores an incredible amount of money.

To understand why this is the case, we need to return to the company’s Rewards program. As mentioned, Starbucks rewards purchases with Stars. Though any payment method earns Stars, customers receive double if they load money onto their Starbucks account.

Why does the company do this? Two primary reasons.

First, it allows Starbucks to receive what is essentially an interest-free loan from its customer base. Starbucks reported holding $1.75 billion in stored value from its loyalty program in its most recent quarter. This was up from $1.56 billion the year prior. Starbucks can, theoretically, earn interest on this capital. At this scale, Starbucks is roughly the scale of a midsize bank in terms of AUM.

Second, because you might forget to spend it. You might add $100 to your account, and then...stop going to Starbucks. The company refers to this as “breakage,” and it’s essentially free money. In 2020, Starbucks recognized $145 million in breakage, up from $141 million. Given that Starbucks brought in nearly $20 billion in revenue, that doesn’t move the needle meaningfully, but it still represents a nice profit worthy of nurturing.

In light of Starbucks’ technological capabilities, it’s tempting to fantasize about the probably-dumb-maybe-brilliant ways the company could leverage its existing platform to extend its lead. Could it bring P2P payments into the app to increase usage? Should you be able to pay with the Starbucks app in different stores? What about buying products from other retailers in the same place you order your coffee? Would it make sense to whitelabel Deep Brew for other businesses, providing they’re not competitive?

No doubt Starbucks has considered all of these things. But when looking at the path the company is charting, Johnson appears to be undertaking a strategy of focused renewal rather than wild imagination.

Grande: Johnson’s Growth Plan

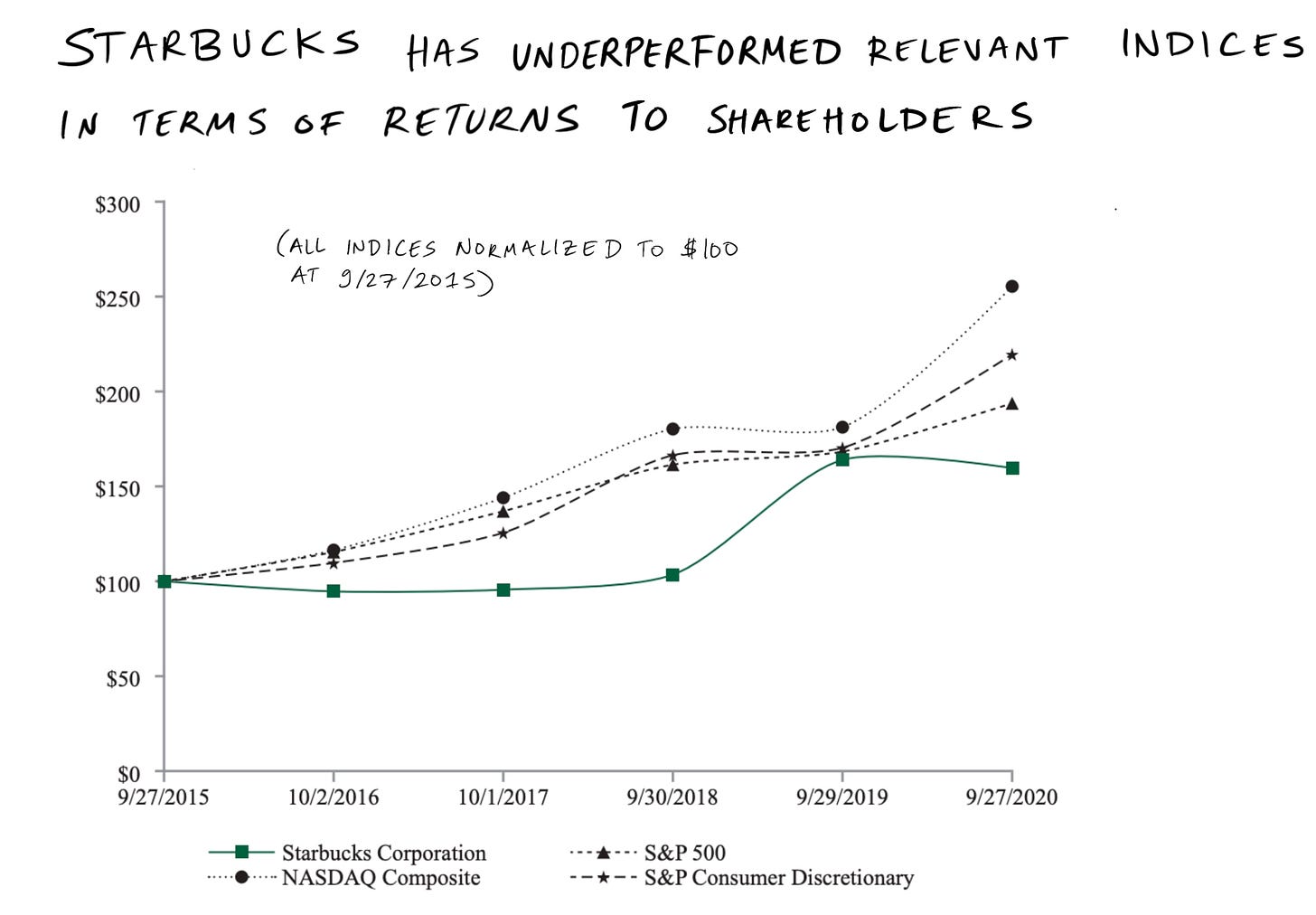

Digging into Starbucks’ financials and recent earnings transcripts gives us a sense of where the company is headed. Though Johnson has succeeded in growing revenue (barring an unavoidable covid-induced slump), a revamp is arriving not a minute too late. Compared to several indices over the last five years, Starbucks has underperformed, despite its stock rising to all-time highs.

Accelerated by the pandemic, Johnson is leading a campaign to alter Starbuck’s retail footprint and production process while growing the company’s position in China.

Pickup

There’s a certain irony in Starbucks’ next incarnation.

Nearly forty years ago, Howard Schultz pushed Starbucks’ owners to change their store so customers could sit down and stay awhile; now, Starbucks wants you to get in and out as fast as possible.

In June of 2020, Johnson announced the company was closing 400 stores and initiating a revamp designed to make it easier to grab a coffee with minimal interaction. Of course, that made sense given the constraints imposed by the coronavirus, but the extent of Starbucks’ investment indicates that leadership sees off-premise locations as a critical component for the future. Indeed, in March of this year, as lockdowns eased, Johnson expanded the plan. Eight hundred stores will now be closed, with 760 of them undergoing renovation to allow for faster service.

In particular, Starbucks is pushing three formats:

Pickup. Customers order and pay ahead, grab their drink from the store, and walk out.

Curbside. Customers order and pay ahead but have their drink delivered to their waiting car.

Drive-through. Customers pull up to a window, order their drink, and pick it up at the next window.

These formats achieve the same end (higher throughput, minimum contact) but are suited to different environments.

Pickup locations are ideal for crowded urban spaces, while curbside and drive-through are suited to suburbs and rural areas. Critically, they offer a higher ROI since Starbucks can save on real estate costs but serve just as many, if not more, customers. Over time and at scale, this may lead to a permanent margin expansion for the business.

Remarkably, in Q2 of 2020, 50% of net sales came from “out the window” orders, a 10% increase from pre-pandemic levels. Clearly, even as stay-at-home softened, a large number of customers preferred this more efficient avenue.

To the extent this mass-refurb proves a sustainable success, Starbucks may look increasingly different than the “third place” Schultz envisioned.

Dark kitchens and delivery

After working with Postmates on delivery for four years, Starbucks jumped to Uber Eats in 2019. That seems to have been the right move with a pilot in Miami extended domestically and internationally, to Japan. (Starbucks is working with Ele.Me, a subsidiary of Alibaba, in China.)

Along with initiatives like Starbucks Pickup, delivery is part of the company’s desire to provide an “effortless” experience.

There are issues with delivering coffee, though particularly concerning temperature and the integrity of foam. There are also opportunities — perhaps the most interesting concerns production.

Rather than operating a store (even a Pickup location), Starbucks can leverage ghost kitchens to make its coffees — production-only facilities not open to the public. Again, this would represent a significant departure from the experiential ethos with which Schultz was so enamored, but as consumers grow accustomed to convenience, moving production to the “cloud” may make sense.

Starbucks has experimented with ghost kitchens in China as part of its partnership with Alibaba. This is notable given that management often uses the Chinese market as something of a testing ground. In 2019, then Chief Financial Officer Patrick Grismer discussed the ghost kitchen pilot, noting:

We're learning from the experience to understand how we might bring a similar model to life in the U.S., particularly in large metro markets like New York.

China

Twelve years after opening its first store in the country, Starbucks is finally giving the Chinese market its deserved focus.

Some of that will have been influenced by the unsustainable blitz campaign coordinated by Luckin, a Chinese coffee chain, since its 2017 founding. Though revealed to be fraudulent last year with the native firm admitting it had juiced 2019 results by at least $310 million, the rapid expansion created a sense of urgency. Indeed, at one point, Luckin surpassed Starbucks to become the largest coffee retailer in the country, mere months before its defenestration.

Starbucks has risen to the occasion and is continuing to double down, even as Luckin falters. Johnson explained the firm’s focus in the most recent earnings call:

China is currently our fastest-growing market, our second largest market overall and 100% company-owned.

In 2020, the US brought in 16.88 billion in net revenue, while China provided $2.58 billion. All other geographies brought in $4.05 billion.

As Johnson noted, Starbucks is in total control of its Chinese operations, which was not always the case. At the end of 2017, Starbucks bought back the outstanding 50% stake in the firm’s “East China” JV from President Chain Store, the owner of 7-Eleven, for $1.4 billion. This matters because it gives Starbucks the chance to earn significantly more revenue. Though about half of Starbucks’ +32,000 stores are licensed, they account for just 10% of total net revenues.

Interestingly, Starbucks’s move to regain operations in China runs counter to moves made elsewhere, further emphasizing the region’s importance. At the same time that Starbucks bought back its China interest, it sold the rights to its Taiwan business. The following year, it did the same in Brazil, and in 2019, it unloaded Thailand, France, and the Netherlands.

Though Starbucks now runs over 5,000 stores in China, it has plans to build many more, with a 14% uptick in locations over the last year, despite lockdown. Just as critically, the company is looking to make its wares available online, even more expansively than in the US.

Seventy-two percent of sales in China were conducted by Rewards members, of which Starbucks now has 16.3 million in the country. In addition to the Starbucks app, consumers can also order via WeChat, JD.com, and Alibaba’s ecosystem.

With Starbuck’s Chinese operations now a forerunner for those in the US, domestic consumers can reasonably expect a very different experience from the coffee company over the next decade.

Venti: Coffee’s frontier

Who is the next Starbucks?

That question was asked on Twitter in response to a post about the company. As suggested by one commentator, perhaps Starbucks is the next Starbucks, as the company disrupts itself from within.

Others will disagree. A new crop of competitors has emerged over the last five years, challenging the incumbent by beginning with tech. These businesses flip traditional unit economics by focusing on small-format stores, reduce costs by abstracting human labor, and may seek to press their connection with consumers into a more durable advantage.

Small format

Six months before Luckin got off the ground, Edward Tirtanata, James Prananto, and Cynthia Chaerunnisa founded Kopi Kenangan. The trio sought to bring small-format, tech-forward coffee shops to their native Indonesia. Rather than taking over an expensive lease for a large space, Kopi operates out of small shops and accepts a high portion of its orders digitally. It also offers delivery through partners Grab and Gojek.

That playbook, when operated sustainably, has proven to be a hit. It allows for capital-efficient expansion, smoother operations, and produces higher ROI.

Kopi has become the “fastest-growing non-franchise coffee chain in ASEAN,” expanding to more than 450 locations. In the process, the company has attracted $237 million in venture funding, with Sequoia India leading both the Series A and B.

In doing so, Kopi seems to have stolen a march on another Indonesian player with a similar strategy: Fore Coffee. Incubated by East Ventures in 2018, Fore has collected just south of $40 million in funding. Like Luckin, Fore has relied on discounting and deals to attract consumer interest, a practice that failed to sustainably bear fruit in Luckin’s case.

Flash Coffee seeks to provide further regional competition. Funded by relentless copycats Rocket Internet, Flash has raised $15 million to expand beyond its Singaporean roots to a reported 10 APAC markets.

Startups are attempting similar plays in the US. Bandit Coffee, launched by a former Uber employee, raised a round in 2020 and runs two Austin locations.

Blank Street, founded in the middle of a pandemic, leverages the small-format store with a twist. Rather than leasing small storefronts like Kopi, Blank Street operates a mix of kiosks and food trucks across New York. Its trucks run on electric power, and Blank Street actively purchases carbon credits in pursuit of its goal to be “the most sustainable coffee brand on the planet.” The mobility of Blank Street’s units provides an added benefit — as demand changes, the company can easily adjust capacity with limited permanent investment.

As with the others mentioned, Blank Street incentivizes ordering through its mobile app, offering rewards. Already, Blank Street has expanded to 5 locations, with founder Issam Freiha noting that further expansion is imminent. Freiha also remarked that despite the coronavirus, “Blank Street’s locations are profitable and growing quickly.”

Robotics

Other startups seek to reduce costs by taking up less space and reducing the need for human labor.

Cafe X has raised $14.5 million to power the production of its “automated cafe system.” Robotic arms place cups beneath espresso machines and foamers before delivering the finished product to the customer. At present, Cafe X appears to operate two locations, both in airports. In addition to running its own shops, the company also accepts inquiries to buy its robotic system, allowing anyone to run a mechanized store.

Truebird seems to be pursuing the same end — removing manual labor — with a more humane touch. If Cafe X’s robotic arms evoke an unwanted medical procedure, Truebird’s magnetic guidance system seems almost like a dance. Mechanical elements are sidelined in favor of a minimalist design. The company was incubated at AlleyCorp and raised $6.6 million from Torch Capital, FJ Labs, and others.

These innovations may compete more directly with brackish coffee vending machines than cafes, but given Starbucks’s interest in small, automated locations, the distance between the two is narrowing.

Consumer app to Super App?

Earlier, I suggested that were Starbucks to enter a more playfully unhinged frame of mind, it might see its way toward providing a venue to purchase other companies’ products, in-app, or offering P2P payments.

Either of those would represent the first step towards the creation of a super app. At first blush, a coffee ordering app doesn’t seem like the right vector through which to build a broader ecosystem. But look a little closer, and there’s a kind of logic to it.

As we’ve established, coffee is a high-frequency purchase, meaning customers open the app multiple times a day. Super apps are built on this kind of repetition. Just as importantly, payments are enabled, and the default behavior is to buy something. Both are, of course, useful in promoting digital commerce.

Of the insurgents mentioned, Kopi seems to be furthest in exploring this strategy. In March of this year, Kopi’s founders reported raising a fund to invest in Indonesian startups. Its first three investments included a podcasting platform, an automobile maintenance business, and an online grocery startup. While the company’s founders refer to the fund as “just a passion project,” high-caliber founders are rarely so uncalculated.

In the next few years, will customers of Kopi be able to buy groceries at the same time that they order a latte? Will consumers order an espresso for delivery, bundled alongside a breakfast order from a local restaurant? Perhaps Kopi Kenangan Fund truly will end up being nothing more than a hobby, but those interested in the space may wish to keep a close eye on its portfolio.

Sitting with Marc Benioff on that balmy Hawaiian day, Howard Schultz knew Starbucks needed to embrace the digital revolution. But he would have been hard-pressed to have imagined the extent to which his dream business would become a tech company. Upon his return, Schultz set in motion a second act that saw Starbucks transform from a coffee house into a consumer app, AI platform, and neobank.

As it looks toward the future in which small-format shops, robotic workers, and super-app style buying habits could reign, Starbucks must attempt to reinvent itself once more. This time, it will need to succeed without Schultz.

The Generalist’s work is provided for informational purposes only and should not be construed as legal, business, investment, or tax advice. You should always do your own research and consult advisors on these subjects. Our work may feature entities in which Generalist Capital, LLC or the author has invested.