Team

Read between the lines.

An uphill battle.

Low-hanging fruit.

Few things muddy the mind quite so effectively as the cliche. In its jaunty assuredness and painful banality, the cliche is like the most onerous of dinner guests: sure of its welcome and yet tedious in the extreme. These soulless words disrupt our speech, invade our thoughts, and impede our understanding. It was political theorist Hannah Arendt that best encapsulated that final point:

Clichés, stock phrases, adherence to conventional, standardized codes of expression and conduct have the socially recognized function of protecting us against reality, that is, against the claim on our thinking attention that all events and facts make by virtue of their existence.

If love and romance are the most common hatchery for cliche — “The first man who compared woman to a rose was a poet, the second, an imbecile" — the topic of “Africa” is not far behind.

In How to Write About Africa, Binyavanga Wainaina satirizes this point and the brainless writing it creates:

In your text, treat Africa as if it were one country. It is hot and dusty with rolling grasslands and huge herds of animals, and tall, thin people who are starving. Or it is hot and steamy with very short people who eat primates.

Unlike any other landmass, Africa seems to reduce writers to semi-poetic nonsense, vague allusion, and cliche. Though most exaggerated in travelogues and breathy film scripts, mainstream business writing on the continent (from beyond the continent) often does the same, in a minor key. Analysis is freighted with presumptions — Africa as a uniformity, the ubiquity of corruption, the totality of governmental incompetence — that block comprehension. Some of these things are true, of course. But in the trite, one-note delivery — cliched in thought if not word — they remove the reader from the reality on the ground.

If there is one thing we hope to achieve in this piece, it is to offer a view of Africa’s tech scene beyond those usual cliches. We will fail at several points; it is impossible to analyze such a massive topic in such a finite space without doing so. But by assembling a team of deep practitioners from distinct geographies and backgrounds, we hope we can bring more nuance to our discussion. On that front, we’ll cover:

Africa’s demographic tailwinds

The continent’s key markets

The power brokers that define its tech scene

Regulators and their tech playbooks

How to manage expansion (or not)

The influx of Chinese and US capital

Misconceptions of the ecosystem

Opportunities in the years to come

We will do our best to read between the lines, discuss the uphill battles entrepreneurs face, and highlight the low-hanging fruit for potential investors. Let’s begin.

Sign up to learn about the next generation of disruptors. Our work exists to help you understand the businesses of the future and to capitalize on change.

Demographics

After an introduction arguing against analyzing Africa as a uniformity, it is unfortunate that it makes most sense to begin by doing precisely that. Though far from the most nuanced view, we must work our way down, and start at a high altitude.

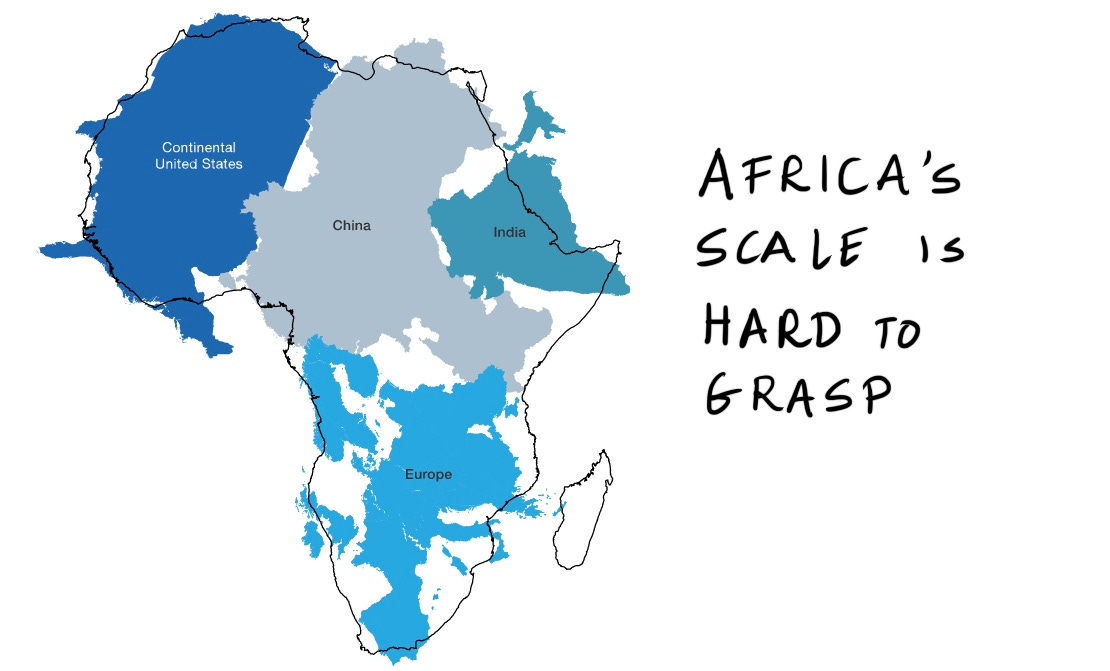

The truth is that for all of the world’s discussion of African vastness, it’s scale is often underplayed. This is not a continent equivalent in size to Europe or the United States; it’s larger than both of those combined, with enough room remaining to accommodate China and India. It is a territory entirely mind-boggling in its expanse.

So far, so cliched. But to add some (prosaic) shade and subtlety to our portrait, this massiveness is not just geographical, but cultural. If Africa’s far-flung borders give it the sense of terranean, external endlessness, the continent is also nearly internally infinite. It is home to more than 1.2 billion people — not far shy of China’s populace — that speak upwards of 2,000 languages. By comparison, Europe houses a little over 200 argots and dialects.

That linguistic multiplicity is coupled with an ethnic one. Across its 54 nations, fully 3,000 different indigenous groups live, including Berbers and Zulus, Yorubas and Igbos, Fulanis and Kikuyus, and, of course, many, many more. These cultures carry traditions that far predate Portuguese, French, Dutch, German, and British colonial occupations.

While those native traditions speak to Africa’s past, those that build and invest in tech companies on the continent spend most of their time thinking about the future. Many may have become convinced of the “African opportunity” by observing the demographic zephyrs powering the continent into the coming decades. No other region on earth is poised to undergo such explosive growth across so many dimensions. Though readers may know the contours of these trends, it’s worth alighting on them further to emphasize their importance.

In particular, we’ll discuss:

A rapidly expanding population

A young, urban citizenry entering the workforce

A rising middle class

Growing connectivity

Population growth

If Africa’s population is close to China’s in size, it will soon dwarf it. Over the next 30 years, the continent’s population is expected to double, reaching 2.4 billion. The effect of this increase on a proportional basis is particularly interesting. Today, Africans make up 16% of the global population; by 2050, they will comprise 25%. That hints at the potential for serious earthly influence.

As is perhaps to be expected, this growth is likely to be concentrated. Consider this the beginning of a leitmotif that will reappear throughout this piece — when looking at growth and opportunity, the same handful of markets often receive mention. With regards to population, half of the expected 2.4 billion will live in five countries: Nigeria (411 million), Ethiopia (191 million), Egypt (153 million), the Democratic Republic of Congo (197 million), and Tanzania (138 million).

Of those, Nigeria and Egypt already represent budding and flourishing tech economies.

Youth and urbanization

What happens when a population rapidly expands? The average age of its citizens declines.

It feels almost a little silly to point this out, and to spend the time referencing the incoming swell of African youth given the measures shared above. But it's a point worth making for its impact on the world of work. Yes, Africa’s growth will mean it is a young continent. It also means it will supply a disproportionate percentage of the world’s working age people, with roughly half of the 2.4 billion expected to be younger than 25 years old. Indeed, over a fifty year timescale, there will likely be more people in that cohort than? in every other G20 country combined.

At a time when many advanced economies are seeing population growth stagnate, this is profound. Organizations in need of employees will find the largest pool available in Africa. As we’ll discuss later, one of tech’s greatest opportunities is in ensuring that young Africans have the skills and training necessary to meet the labor demands of the future.

As is to be expected, these new generations will predominantly cluster in cities, creating economic powerhouses with relatively small footprints but considerable spending power. A frankly staggering 80% of population growth will accrue to urban centers, creating the world’s largest metropolitan areas. By 2050, ten of the biggest 50 cities will be Africa. In just the next ten years, a collection of Africa’s biggest 18 cities will reach $1.3 trillion in spending. That’s the kind of commercial scale that can support and galvanize new ventures.

With as many Africa cities with more than 1 million inhabitants as North America already, the truth is that the shift is already well underway.

Rising middle class

Just as with the prior section, a certain amount of deduction can be used to reach the conclusions proposed in this next section. As Africa grows and urbanizes, spending power is expected to increase. In particular, the continent will see a rising middle class, expected to reach 580 million by 2030, with an upper class of an additional 116 million.

For context, that’s more than double the current US population. Though such figures suggest a tidal wave of prosperity, some gradation and distinction is required. Yes, the size of Africa’s middle and upper classes will be enormous; but its spending power isn’t equivalent.

That’s because what constitutes the middle class in one country is not the same as in another. Though reasonable studies may set benchmarks differently, it’s inarguable that the average middle class citizen in America makes considerably more than an African counterpart. A Pew Research study set median US household income at $74,000 or roughly $200 per day. A Brookings report on Africa’s middle class study set the lower boundary at just $2 per day. The same report argued that to be a part of the upper class, African residents would need to bring in more than $20 per day. Orders of magnitude separate the delineation in one country to those on the continent.

This isn’t to say that the absolute numbers are not impressive or worthy of note. By 2025, African consumer spending is slated to reach $2.1 trillion, rising to $2.5 trillion by 2030. While US consumer spending tops $12 trillion, India’s comes in closer to $1 trillion. Clearly, the latter country has been able to develop an extraordinary, prosperous tech scene, even if there remains plenty of room left to run. In time, Africa’s ecosystem may look similarly rich, with a burgeoning middle class partially to thank.

Growing connectivity

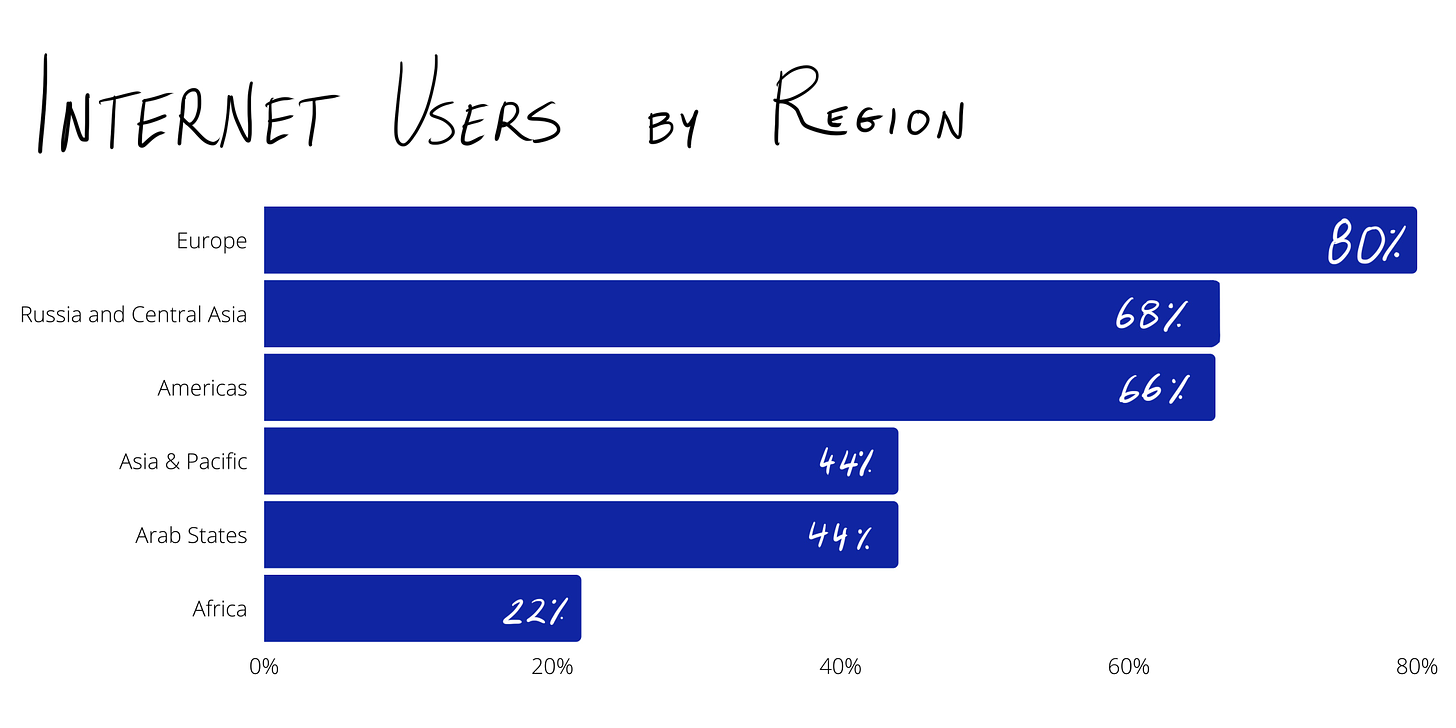

For all the discussion of developing countries “leapfrogging” the developed, Africa still lags when it comes to internet connectivity and mobile phone penetration. Obviously, those represent rather critical ingredients in the construction of a thriving tech market. As things stand, just 22% of Africans have internet access, far below the 80% of Europeans, 68% of Russians and Central Asians, and 44% of those in the Asia Pacific region.

Though better, the proportion of the population that uses a mobile phone is also low. In Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), for example, 45% have a device, or 477 million people. These are large absolute numbers, but of course there’s still considerable room to run. As with so much in the world of African innovation, what oftens seems to be a deficiency can quickly be reframed as an opportunity. Certainly, connectivity is comparatively low, but it’s grown at a remarkable clip. In 2005, just 2% of Africans could access the internet. Two percent! By that point in the US, 68% already had their modems fired up and were patiently waiting 30 minutes to download a JPEG. Viewed through that lens, figures look rather rosier.

More is to come. Again, returning to mobile phones in SSA, an expected $52 billion in infrastructure investments should increase penetration over the next four years. In that time alone, the percentage of the population with access will reach 65%, with a full 475 million receiving mobile internet access.

In a matter of years, African connectivity will look less like a question of potential, and more like a firm reality. That will serve to bolster the crescive venture beginning to flower.

Key markets

Now we can begin our delineation in earnest. VCs do not invest “in Africa.” Rather they back companies in specific countries and markets. Each of these has unique complexions with different sectoral specializations and modes of operating.

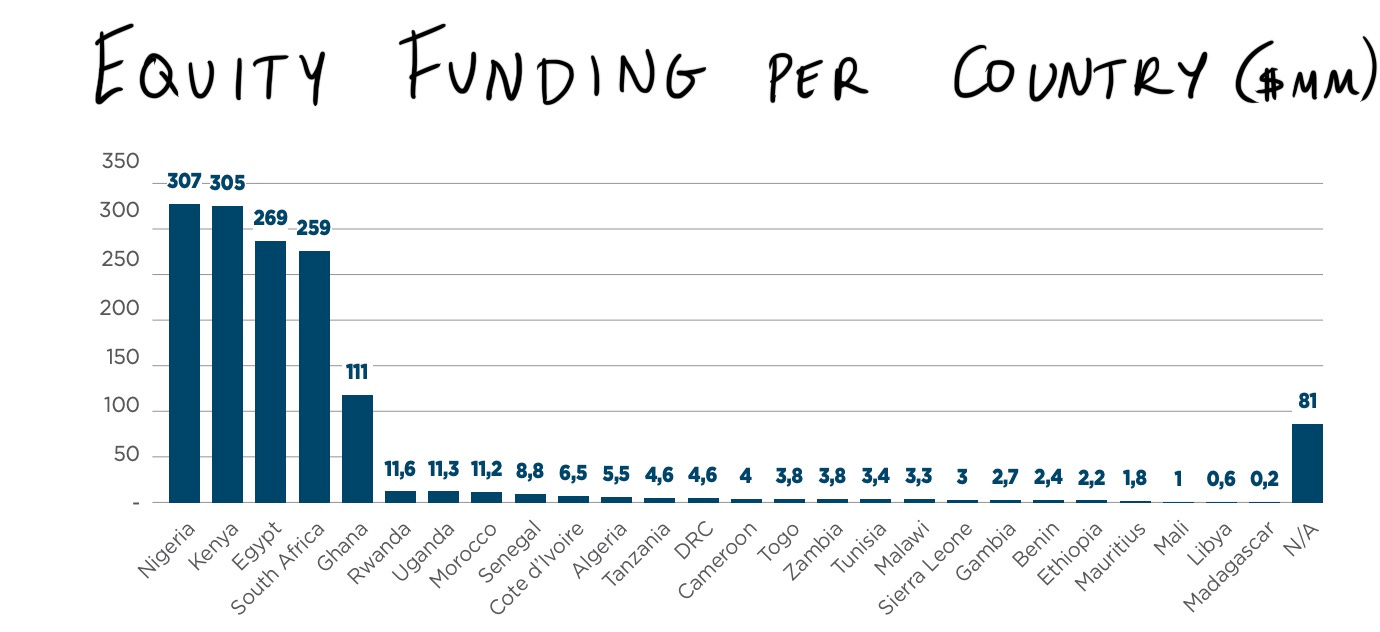

First a look at the high level figures: per Partech’s 2020 report, 26 African countries attracted venture capital funding in 2020, for a total of $1.43 billion. This sum might seem small on a global scale. Indeed, it represents less than 0.5% of the estimated $300 billion in VC raised last year. But it’s really an illustration of the region’s advancement. Ten years ago, the African startup and venture capital ecosystem was virtually nonexistent, and since 2015, the continent has seen over 40% in annual VC capital growth. That’s a startling trajectory.

As you’d expect, the distribution of this capital is far from equal. Just as Silicon Valley attracts more money than other US geographies, or the UK entices larger contributions than Estonia, Africa’s ecosystem is concentrated. The degree of this consolidation is indicative of the scene’s relative immaturity: 80% of total funding going to just four countries — Nigeria, Kenya, Egypt, and South Africa.

While each market deserves considerably more attention, for the purposes of this piece, we’ll touch on just these four power players for the time being, to give a flavor for their particular national dynamics.

Nigeria is perhaps the best single national market. It has many of the ingredients to support venture scale businesses, including a 200 million population, strong tech talent, robust angel networks, and impressive insurgents with Flutterwave and Interswitch based in Lagos. As those two businesses suggest, Nigeria is particularly renowned for its fintech scene, which continues to grow. It’s perhaps no wonder, then, that the country retained its title as the “#1 destination” for investment, receiving 21% of funding.

Not far behind Nigeria from an investment perspective is Kenya. Though the country has a smaller population of roughly 50 million, it’s become a hub for agricultural tech. Remarkably, of funding in this sector, a full 79% went to Kenyan startups. A significant influence on this figure was the $85 million Gro Intelligence picked up in 2020. Beyond this space, Kenya also has deep roots in fintech. Indeed, much of the country’s success as a tech center can be traced back to Safaricom, owner of money transfer provider M-Pesa. That service has enabled entrepreneurship in a manner few other products have.

Egypt was the busiest nation in terms of the number of deals conducted over the last year, with 24% occurring in the North African country. It was also the fastest-growing market among the top four with an annual increase of 28% in invested capital. That comes from both local and foreign investors. Even famed firm Sequoia is getting into action, recently leading a $5 million investment in Egyptian neobank, Telda. Much of Egypt’s allure comes from its network of skilled founders and operators. The successful exits of Careem (sold to Uber) and Fawry (publicly traded) have birthed a stratum of financially successful tech workers ready to build again, or invest in the next great Egyptian startup. As the Telda round suggests, Egypt attracts interest in fintech, while also dominating in logistics, mobility, and edtech.

Our journey southwards (by way of Cairo) culminates in South Africa. The richest country on the list by a GDP per capita basis, the tip of the continent is home to a thriving financial sector, even if it does not boast the financial tech clout of Nigeria. South Africa is also home to media heavyweights like Naspers, a global player with a strong center of gravity. The country is particularly dominant in the enterprise software space, attracting almost half of all funding.

Beyond these four nations, there are a plenitude of ways one might choose to carve and limn Africa’s VC ecosystem. Should North be compared to South? East to West? Urban to rural? Landlocked to coastal?

Each attempt might bring out intriguing narratives, but one of the most apparent distinctions can be found when cleaving along linguist lines. Specifically, there is a huge gulf between the funding Anglophone and Francophone countries receive. In 2019, just $54 million went to French speaking nations. This past year, Morocco led these countries in funding with just $11.2 million, barely an appetizer on Sand Hill Road.

(The wise will recognize the clear opportunity here. Francophone Africa is home to 430 million people, with a shared currency covering 200 million of those. Moreover, the region is expected to comprise 62.5% of Africa’s growth over the next several years, according to the World Bank. Intriguing.)

We began this section by reframing the total dollars invested in Africa as a growth story. Yes, the numbers might seem small, but look how far they’ve come, we told you. That is one narrative — may we offer you another?

These numbers are insane. Perhaps our morning caffeination has caught up with us — Seize the day! Do the things! Eat the world! — but let’s return to the absolute figures here. Nigeria — as in that massive, populous, vibrant nation — received just $307 million in funding. That’s less than virtual event platform Hopin’s Series C, less than GoPuff’s Series F, less than crypto hardware Ledger’s latest, a sneeze more than vertical farming company, Bowery.

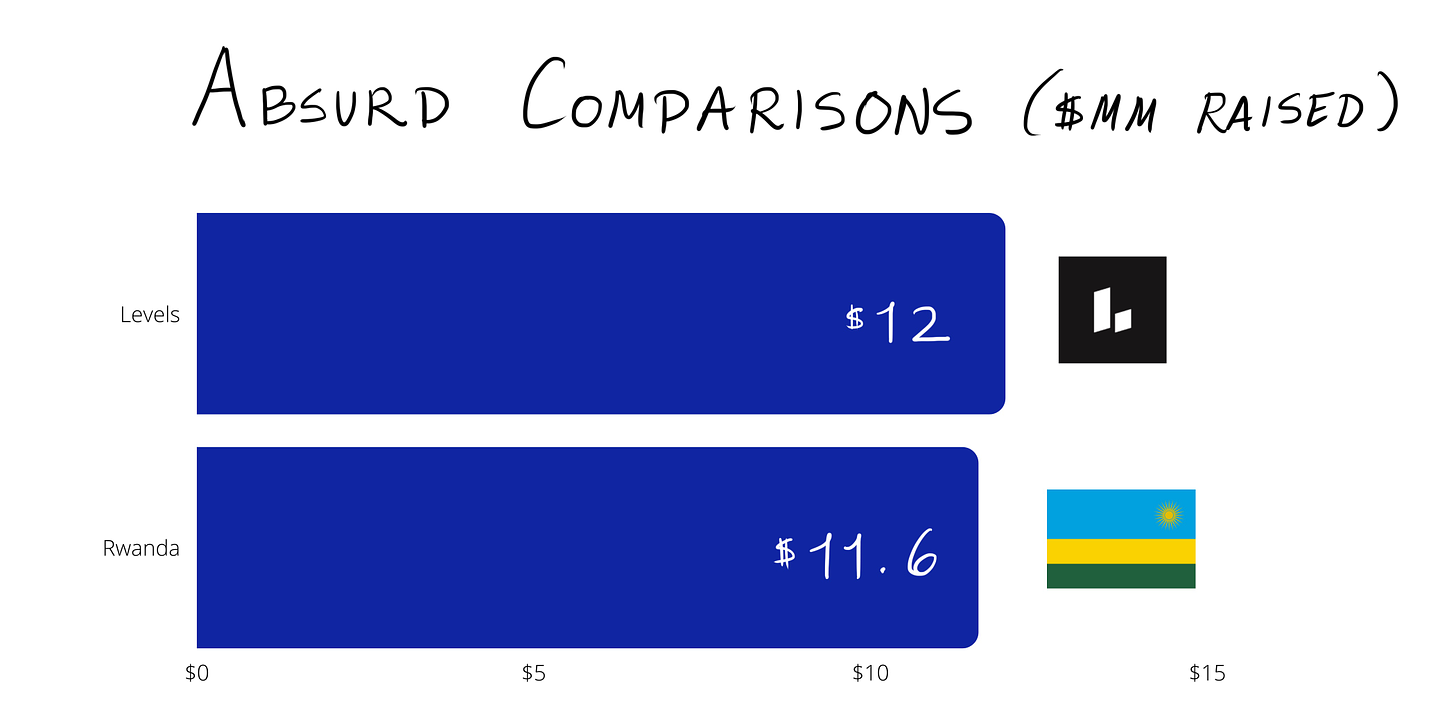

Rwanda raised just $11.6 million in VC money. Levels, a company that sells a biometric patch that tells you oatmeal spikes your blood sugar, raised $12 million for its seed round.

With all due respect...are you f**cking kidding me? This isn’t a slight on the companies that have astutely picked up cheap capital, but on the uninventive VCs lemminging into the same handful of Western entities. Purely pragmatically, should we really believe there’s greater upside to be found in backing the truck up into some single US company than in funding dozens, perhaps hundreds, of potential entrepreneurs in Lagos, Cape Town, or Cairo?

Framing Africa’s VC scene in these terms shows just how much more room there is to grow. Reasonably, external investors may feel they lack the competence to evaluate companies in the ecosystem (though, VCs don’t usually lack confidence), but with Western valuations skyrocketing and national markets radically under-addressed, they may want to catch up.

Understand the world's most consequential tech companies before they IPO. Don't miss our next email.

Key players

If a Martian landed on earth and wanted a breakdown on US tech, where would you begin?

Ok, that’s actually pretty easy. Elon, the Man of Mars himself.

After that would come a string of words and names and companies:

Remote work, Zuckerberg, App Store tax, Google(plex), Epic flex; former-husband Bill Gates, TechCrunch, fundraising lunch, another string of vest dates; YC orange, Airbnb pink, Twitter blue, Twitter threads, “There’s someone in your Zoom waiting room;” Sequoia advances, Tiger preemptions, WeWork’s redemption, Clubhouse’s declension; “Stripe is undervalued,” “Figma is undervalued,” “Microsoft Clippy is undervalued”; Mary Meeker, bubbles, froth, foam, phones, Chamath’s abs, $80 million pre (product), return to normalcy, “$200 million? Normal C”; mmhmm, “can you hear me? I think you’re muted”; Sundar, Satya, Sahil, rolling funds, Gurley, Kalanick, class panic; “a16z is a media company,” Substack usurps the Medium Company, NFTs, creator economy; Fast hoodies (pace slows), checkout wars, former-husband Jeff Bezos.

(We don’t have to tell the Martian about Founders Fund. He deserves to be happy.)

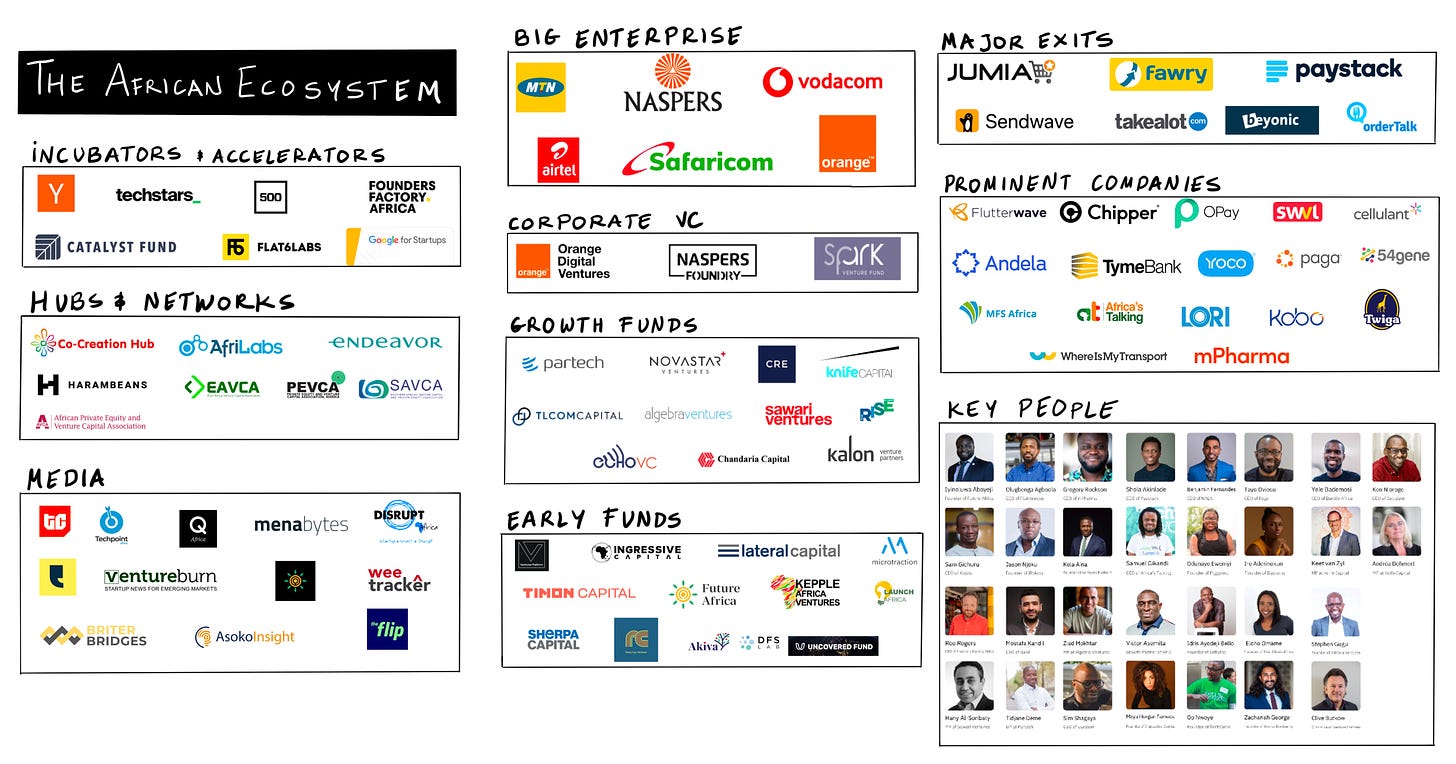

Consider this next section our attempt to do the same. It is a lightning ring-a-round of the African ecosystem which may, at times, read like a word salad. The hope is that for those that want to go deeper this provides a good overview of the main players. Though we’ve tried to be comprehensive, it is by no means definitive.

Let’s take a look at the continent’s leading accelerators, venture firms, leading entrepreneurs, and other power brokers.

Accelerators

Accelerators serve a crucial function in startup ecosystems. They train entrepreneurs, create social capital through cohorts, and connect companies with funding sources. Though comparatively underdeveloped, African startups do still have options, both at home and abroad.

Even though it's based in the US, Y Combinator plays a real role. Since 2015, the accelerator has admitted 49 African startups, including Flutterwave and Paystack. Those wins seem to have intensified the accelerator’s resolve, while also encouraging more African founders to apply. Other notable YC companies include 54Gene, Kobo360, Helium Health, and BuyCoins. Collectively, the African portfolio has raised more than $500 million in follow-on funding. Given the numbers shared in the section above, it’s clear how much easier companies that receive the Great Orange Benediction can raise additional capital.

Other prominent US organizations also play a role, including 500 Startups and Techstars. When Dave McClure took a trip to Africa in 2017, 500 Startups had made around ten investments on the continent. Just four years later, that figure stands at over 74, a major increase. Techstars has opened up various local chapters over its history, often in conjunction with corporate partners. For example, in 2016, the incubator launched a Cape Town location with Barclays. Techstars regional investments include Eversend, Max.ng, MDaaS Global, and OnePipe.

The Founders Factory, based in the UK, took a similar approach, setting up its African arm in Johannesburg. The startup builder partnered with South Africa's Standard Bank Group, the largest bank in Africa as of 2020. That’s proven to be a fruitful formula with Founders Factory Africa backing more than 20 companies since inception.

Catalyst Fund, managed by BFA Global, supports early-stage fintech entrepreneurs across emerging markets. In pursuit of that mission, Catalyst has focused on Africa, with 29 of its 45 portfolio companies coming from the region. Their portfolio has collectively raised more than $226 million in follow-on funding, another promising sign.

Village Capital is similarly global in scope with offices in Mexico, India, Colombia, the UK, the US, and Kenya. The accelerator invests across agtech, fintech and the future of work and has backed more than 100 entrepreneurs on the continent. Village has also used its curriculum to train 64 entrepreneur support organizations in Africa's Anglophone, Francophone, and Lusophone countries. As alluded to earlier, this badly is needed.

In North Africa, companies will often seek out Flat6Labs. The firm has extensive experience supporting companies across the region with offices in Egypt and Tunisia. In May 2021, Flat6Labs announced the second close of its Egypt fund. The fund had targeted ~$3.2 million but brought in $13 million, a sign of the trust the incubator has earned, and the opportunity ahead. Flat6Labs’s portfolio includes Accel-backed Instabug.

Lastly, Google is also in on the action. Via its Startups Accelerator Africa, the company, has worked with up to 50 startups across 17 African countries. The program seems to be picking up pace — almost half of those participants arrived in 2020 alone.

Corporates

Although it's usually enjoyable to poke fun at big business (at least from the floating lily pad of startup world), large enterprises can galvanize entrepreneurship. Critically, they can serve as anchor customers, sources of talent, and providers of funding through corporate VC arms. Of course, they can also crush it, rolling out competitive products, lowering their prices, or reorganizing themselves to capture a new share of the market.

Banks and mobile network operators (MNOs) are the megalodon’s swimming beneath the surface in the African tech scene. The biggest beasts include MTN Group, Airtel Africa, Safaricom, Vodacom, and Orange Group. Many of these companies have either explicit or implicit backing from native governments and are considered “national champions.”

In addition to being dominant players in the ecosystem, these MNOs also serve as gatekeepers to crucial industries. If they want to, they can make it very difficult for insurgents to enter the market, particularly if they sense a threat. Unfortunately, they have a history of being cagey and defensive in their relationships with the startups. A case in point is the ongoing dispute in Senegal between the startup Wave and the incumbent Orange. Wave grew thanks, in part, to its innovative, low-cost business model; when Orange sensed they might be losing ground they both drastically lowered their prices on competing features, and shut off access to Wave on their telecom networks.

These MNOs are also savvy enough to realize when they should reorganize themselves to maximize value. MTN and Airtel are spinning off their mobile money units to position these subsidiaries as pure-play fintech, unlocking higher multiples. MTN’s Mobile Money unit is valued at an estimated $5 billion, while Airtel’s is at $2.65 billion. Again, this can be seen as a maneuver clearly influenced by bottom-up competition. As fintech insurgents have begun to challenge their supremacy, the MNOs have decided to act.

Of course, the MNOs also play nicely with startups when it suits their purposes. Several of Africa’s biggest companies (including one non-MNO organization) have leveraged their positions to create thriving corporate VC funds.

MTN Group is one such player. The company operates in 15 African countries with 22.2 million mobile money subscribers, and has boasted a thriving venture and incubation practice for years. Indeed, MTN Group joined Rocket Internet and Millicom in setting up “Africa Internet Holding,” which later became Jumia Group in 2013. That proved to be a good bet: estimates indicate that MTN made at least $160 million in profits on its work on Jumia. MTN has continued to invest strategically over time.

Despite the brutality of their engagement with Wave, Orange Group is another company with venture ambitions. The telecom and fintech business — which includes Orange Money alongside a more richly featured digital bank — has a particularly strong hold in West Africa. Their fund, Orange Ventures, manages assets of €350 million and invests in Africa, Europe, North America, and the Middle East.

Safaricom, the owner of M-Pesa that we discussed earlier, dominates Kenya’s telecom industry, with an estimated 63.6% market share. In 2020, the company announced a partnership with the Nairobi Securities Exchange through which it would allocate a further $5 million to its Safaricom Spark Fund.

Finally, we couldn’t talk about corporate investors without touching on Naspers of South Africa. Founded in 1915, the company has tentacles in several different business lines, including media, fintech, and food delivery. In addition to its core operations, Naspers has a prosperous venture arm with a sterling track record. Indeed, the company is one of the largest investors in Tencent, having purchased a third of the company in 2001. That turned out to be one of the greatest investments of all time. In 2019, the company launched Naspers Foundry, a $100 million fund focused on the country’s startups.

Notable startups and exits

Every ecosystem needs a win.

One of the reasons tech scenes become stronger over time is that the winnings from significant exits — both talent and capital — are reinvested. When a company like Airbnb goes public, employees receive a payday which they can use to found a business or angel invest.

Less tangibly, big exits (and large raises) have considerable psychological impacts on future founders. Seeing that others can succeed in similar circumstances can persuade more talented individuals to give entrepreneurship a shot.

Africa needs more winners. Though a few companies have broken out and achieved significant exits, they are few and far between.

One exception is Pan-African e-commerce company Jumia, which went public on the NYSE in April 2019. In doing so, Jumia became the first startup from Africa to list on a major global exchange. While the company has struggled since its debut — closing markets and losing money — it nevertheless represented a landmark. In August of the same year, Fawry, an Egyptian payments fintech, also went public on the Egyptian Stock Exchange at a $1 billion market cap. Thankfully, Fawry has moved in the opposite direction, doubling in value.

Again, though relatively sparse, Africa has seen some notable M&A activity. Last year, payments company Stripe acquired Paystack for $200 million. The Nigerian company had taken in just over $10 million in venture funding, locking in a big win for investors. Similarly, WorldRemit, a UK online money transfer company, acquired Africa-focused remittance firm Sendwave, also in 2020. Though that deal got less buzz in mainstream Western tech circles, it was the larger transaction, valued at $500 million.

There have been smaller transactions, too. In 2017, after making several investments into the company, Naspers acquired South Africa’s largest e-commerce retailer, Takealot; they bought out Tiger in the process. In 2018, UberEats acquired OrderTalk from Knife Capital. Finally, in 2020, mobile money gateway MFS Africa acquired Ugandan player, Beyonic.

A good, if imperfect, proxy for future exits is the number of growth rounds a region sees. In that respect, Africa is trending in the right direction with an increasing count of financings above $100 million. Companies that receive these mega-rounds are often marked out as regional winners, attracting further interest from large foreign investors.

In March 2021, New York-based private investment firm Avenir Growth Capital and Tiger led a $170 million round into African payments company Flutterwave, valuing it at over $1 billion. In total, Flutterwave has raised $225 million and is one of the few African startups to have secured more than $200 million in funding. Chipper Cash, a three-year-old startup that facilitates cross-border payment across Africa, also closed a $100 million Series C in May.

OPay is an influential insurgent with a different composition. Owned by Chinese investors, the company was reported to be raising $400 million to fuel further expansion. OPay raised two large rounds in 2019 — $50 million in June and a further $120 million Series B in November. The same year, developer outsourcing company Andela raised a $100 million Series D led by Generation Investment Management—a firm co-founded by former US vice president Al Gore.

If you’re noticing a fintech-focused theme (with the exception of Andela), the final highlighted startup will confirm your suspicions. Also in 2021, South African digital bank, TymeBank, secured a ~$109 million investment. The neobank offers a low cost bank account and savings product. At the time of the announcement, TymeBank revealed it had about 2.8 million customers.

There are several dozen other companies worthy of discussion. Other well-funded African startups include Yoco, Cellulant, Paga, Swvl, MFS Africa, Africa’s Talking, Lori Systems, 54Gene, Kobo360, WhereIsMyTransport, Twiga Foods, and mPharma.

Notable startups that have raised in 2021 include Kuda (Series A, $25M), LifeQ (Series A, $47M), Mozart (Series A, $15M), Telda (Pre-Seed, $5M) led by Sequoia Capital. Bosta (Series A, $6.7M), Carry1st (Series A, $6M) led by Riot Games (developer of League of Legends), Expensya (Series B, $20M), Appzone (Series A, $10M), PayMob (Series A, $18.5M), Si-Ware Systems ($9M).

Hubs and networks

What is a “hub”?

While it’s tempting to lump all manner of companies into the “accelerators” category, key players often don’t fit that mould. Rather these “hubs” or “networks” operate more similarly to a co-working space, but provide the social fabric for startups to flourish and the ecosystem to grow.

The most well-known hub across the continent is Nigeria’s Co-creation Hub (CcHub). Based in Yaba, Lagos, and founded in 2011 by Bosun Tijani, some of Nigeria’s most prominent startup founders trace their beginnings to CcHub. It’s also become something of a pilgrimage for foreign tech celebrities: when Mark Zuckerberg visited Nigeria his first stop was at Cc. Other notable tech figures that have visited include Jack Dorsey and Nat Friedman, CEO of GitHub.

Since its founding, Cc has expanded beyond Nigeria to East Africa by acquiring another well-known player, iHub. On top of other services it offers to startups, CcHub runs an investment vehicle called Growth Capital Fund. AfriLabs is another provider of tech hubs, with locations across the continent.

The Harambean network offers something a little different. More of a membership club, Harambean has nevertheless attracted an impressive coterie of founders and builders to its network. Over the last decade, the group has helped spawn unicorns such as Andela, Flutterwave, and Yoco, which have collectively raised over $700 million.

Perhaps surprisingly, global entity Endeavor has developed real influence on the continent. Its “entrepreneurs network” now has over 80 African members. Endeavor invests and supports its founders like a traditional fund, but also runs extensive social programming so that it’s community can coalesce.

Finally, the continent also has associations that bring together venture capitalists and private equity investors at a regional level — East, West, and South — and the continent as a whole. The African Private Equity and Venture Capital Association is the pan-African industry body promoting and enabling venture capital and private investment.

Venture Capital

As we touched, Africa’s VC scene is small, but growing.

If the continent has a Sequoia equivalent, it's arguably Partech. The French firm has been operating in the ecosystem for some time and continues to scale up its involvement. Partech announced the final closing of a new €125 million vehicle in January 2019 — not that large by US fund standards, but equivalent to nearly 10% of all capital deployed this year. (Forgive these constant comparisons, but it is easy to lose track of the differences in scale.) Partech has managed to woo more than 40 different LPs, including the European Investment Bank, the IFC, KfW, the German Development Bank, FMO, and the African Development Bank Group.

Novastar Ventures, a Nairobi and Lagos-based investment firm, announced the closing of $108 million in commitments to launch its Fund II (NVAFII), bringing its total capital to $200 million. The amount was a 35% uplift on Novastar’s maiden fund, with sizable final closings held amid the pandemic, another signal of strong investor trust. Like Partech, Novastar has received backing from several of Europe’s most prominent development finance institutions.

We’ve already touched upon the thrillingly-monikered Knife Capital. The Cape Town based fund is raising a $50 million vehicle to back startups at Series B and beyond. Interestingly, Knife began as a PE fund, shifting to a more traditional venture playbook over time. Significant exits include Visa’s acquisition of fintech Fundamo and Uber’s orderTalk’s buy mentioned earlier.

Other notable growth stage VCs include TLcom Capital, EchoVC, CRE Ventures, Kalon Venture Partners, Algebra Ventures, Sawari Ventures, TPG, and Chandria Capital.

While the funds above tend to invest in more mature companies, Africa is developing an early-stage venture market.

For example, Paystack was backed by Ingressive Capital and Ventures Platform, both firms that invest at the pre-seed and seed stage. Another firm that plays at this stage is Future Africa, led by Iyinoluwa Aboyeji, one of the analysts on this piece. The same is true of Lateral Capital, run by Steven Grin, also a contributor.

Other pre-seed and seed-stage investors across Africa include Kepple Africa Ventures, Launch Africa, Sherpa Ventures (a contributor), Rally Cap Ventures (ditto), Timon Capital (of course), Akiva Ventures (yes), Uncovered Fund, DFS Lab, and Microtraction.

We hope many more will come into the market at every stage.

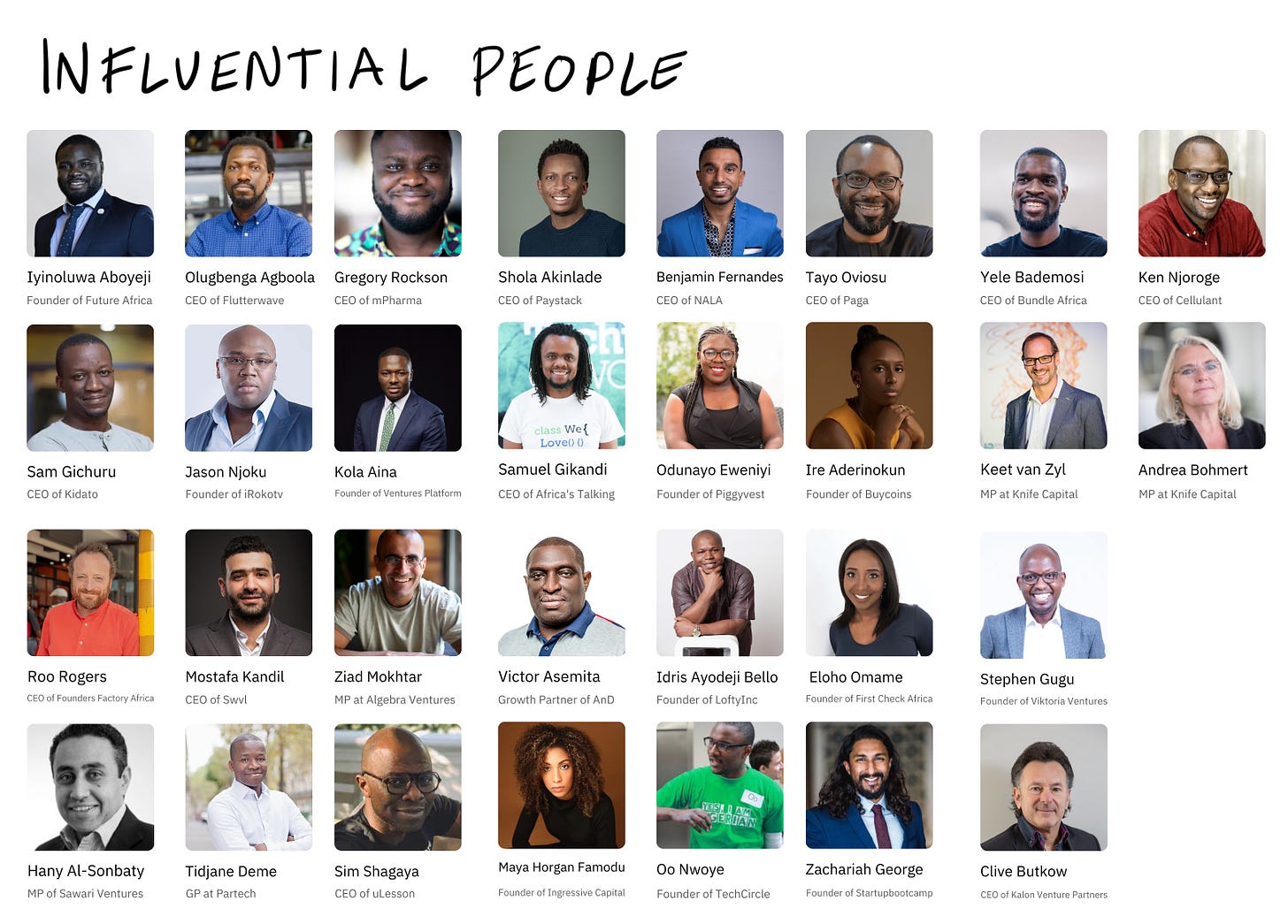

Individuals

Like a couple putting together their list of potential wedding invites, we are certain we’ve missed several important people in this next section. With that caveat, let’s survey some of Africa’s tech power brokers — the movers and shakers and deal-makers.

We’ll start with Nigeria. One of the most recognizable figures is someone we’ve already mentioned: Iyinoluwa Aboyeji. As a co-founder of Andela and Flutterwave and General Partner of Future Africa, Aboyeji’s name is synonymous with startups and venture capital in Africa. We promise he didn’t write this section.

Fellow Flutterwave co-founder Olugbenga Agboola has similar sway. “GB,” as he’s often known, has scaled the payments company to unicorn status, while kicking off an angel investing practice. With mPharma founder and CEO Gregory Rockson, GB invested in Kenyan startup Kibanda Topup.

Jason Njoku was among the first group of founders that raised significant venture capital in Africa. His company, iRokotv, a subscription on-demand video platform for Nigerian films, brought in more than $40 million from Tiger, Kinnevik AB, and Canal+. The French firm acquired iRokotv’s ROK in 2019. Jason is an active angel investor, having backed Paystack. Through his blog, Jason documents lessons learned as an entrepreneur and investor — a favorite resource for many builders in the country.

Kola Aina was a coinvestor of Njoku’s on Paystack, via his firm Ventures Platform. PiggyVest, Migo, MDaaS, and Kudi are also among his portfolio. Kola’s been active in the ecosystem for at least five years.

Bosun Tijani, the founder of CcHub mentioned earlier, also ranks among the top figures in Nigeria. And notably, Paystack co-founder Shola Akinlade often helps African startups looking to join YC.

In Kenya, Y Combinator alumni Sam Gichuru is a prominent figure. He’s the founder of Kidato, an online school for K-12 students in Africa, which took part in YC’s W21 batch. It’s worth noting that Sam is also the founder and former CEO of Nailab, a start-up hub and incubator. When Jack Ma announced his plans to grant $10 million to African startups in 2018, Sam and Nailab were selected to lead the efforts.

In Tanzania, Benjamin Fernandes is something of a power-broker. A YC alumni and co-founder of the Accel-backed NALA, Fernandes organizes monthly “Build Our Africa” sessions interviewing other African founders. Tayo Oviosu, Samuel Gikandi, Odunayo Eweniyi, Ire Aderinokun, and Yele Bademosi have all joined.

In Kenya, Cellulant co-founder and former CEO Ken Njoroge stands out. He co-founded the company in 2004 and raised a hefty round from TPG’s The Rise Fund. Stephen Gugu, founder and director of Viktoria Ventures, is another notable figure.

South Africa’s Keet van Zyl is a veteran of the VC industry. Together with Andrea Bohmert, he serves as the managing partner of Knife Capital. Clive Butkow from Kalon Venture Partners and Founders Factory Africa’s CEO Roo Rogers have also built conspicuous careers.

In Egypt, Mostafa Kandil possesses considerable clout. CEO and co-founder of Swvl, Mostafa previously worked as a Market Launcher at Careem, which Uber acquired in 2019 for $3.1 billion. Other notable figures in Egypt include Ziad Mokhtar, the managing partner of Algebra Ventures, and Hany Al-Sonbaty, the managing partner of Sawari Ventures.

Other key figures include Tidjane Deme from Partech, uLesson CEO Sim Shagaya, angel investor Idris Ayodeji Bello, former Director of Endeavor in Nigeria and now co-founder of First Check Africa, Eloho Omame, Ingressive Capital founder Maya Horgan Famodu, Growth Partner of AnD Ventures, Victor Asemota, TechCircle founder Oo Nwoye, and Startupbootcamp founder Zachariah George.

Media

This has already been a rather lengthy section, so we’ll keep this final point brief: Africa’s tech media system remains inchoate. Though there are some dedicated outlets, there’s room for significantly more players and deeper commentary.

Those interested in digging deeper might enjoy (virtually) paging through TechCabal, TechPoint, Menabytes, Disrupt Africa, Ventureburn, Briter Bridges, WeeTracker, Asoko Insight, The Subtxt, and Quartz Africa. The Flip and Invest in the Future podcasts are great listens and host many of the luminaries listed above.

To help get you started, we’ve linked to a few favorite readings and resources at the end of this piece.

Regulation

Remember at the beginning of this piece when we mentioned how writing about Africa often slips into sluggish characterizations of kleptocrats and bureaucratic sloth?

Though there’s plenty of variation and nuance to be disentangled, that is partially true. Navigating governments and regulatory issues in Africa is thorny, and personal relationships do seem to matter more than in many other parts of the world. Regulatory capture is a real threat, and partially because of this, unrest has roiled the continent at different times. Many such dissensions take place along generational lines: young people from Nigeria to Kenya to Egypt are pushing for change, protesting against geriatric governments.

This tension adds risk for investors.

One anecdote: a senior investment banker that helps African companies list on Western exchanges noted it was virtually impossible to sell the story of an enterprise concentrated in just one country. The potential for political risk makes it too unattractive. Instead, investors are typically only interested in businesses that spread regulatory risk across multiple national markets.

Below, we’ll explore the dimensions of this risk, and how the public sector influences the tech ecosystem. In particular, we’ll highlight three regulatory practices that impede entrepreneurship:

Banning then learning

Moving slow

Succumbing to tradition

Banning new technologies

One of the most delightful, capering episodes of the current decline of the American Empire was Sundar Pichai’s hearing in front of congress. Perhaps because the Google CEO is a soft-spoken figure, his energy seemed particularly at odds with the hilarious, artless bombast of our elected representatives.

In one particularly enjoyable sequence, California Representative Zoe Lofgren tried to wrap her head around how Google generated the results for its Image search. Why, she wondered, did Donald Trump appear when she typed the word “idiot” into the search bar?

Sundar tried his best to explain, but Lofgren wasn’t entirely convinced. Just to make sure she understood, she asked the CEO to confirm that it wasn’t just “some little man sitting behind a curtain figuring out what we’re going to show the user.” Right?

Right, Pichai assented, bashful smile just about curbed.

Dozens of other gleefully bungling interludes could be picked, likely from countries around the world. Politicians have proven to be especially, almost virtuosically inept at grasping the basics of technology. In that respect, Africa’s regulators are no different. The action they tend to take when faced with incomprehension, however, absolutely is.

If America’s strategy has been to do nothing, declare a catastrophe has occurred, then continue to do nothing, African governments usually ban first, ask questions later.

Neither approach is perfect, though the former does have the benefit of empowering innovation — even as it has permitted social media giants to carjack our cognitive functions. (🎵“It’s the remix to cognition/Think my left eye is twitching/Momma I’m trolling somebody/Now I’ll do some catfishing.”🎵) The other approach stops startups dead in their tracks.

For example, in just the last 18 months, Nigeria’s regulators have acted such that numerous startups have been forced to duck-and-weave their way to safety. We can look at four examples, covering crypto, equity trading, on-demand taxis, and Twitter.

Earlier this year, Nigeria’s Central Bank (CBN) forbade financial institutions from holding, trading, or transacting with cryptocurrency. That move came in response to a huge uptick in crypto trading volume in the country last year, with regional exchanges like Yellow Card growing volume by 1,840%. The platform is often used for remittances, and 50% of its user base is Nigerian. Global exchanges like Binance also saw volume soar.

On one level, the CBN’s maneuver made some sense. It was, in effect, an attempt to maintain sovereignty and keep control of the financial sector, particularly the traditional practice of banks converting deposits into government debt.

But that self-interested pragmatism also discourages innovation in a space in which Nigeria is a genuine global leader. As a percentage of the total population, more people hold crypto in Nigeria than in any other country on earth. Thirty-one percent of Nigerians HODL, compared to just 6% in the US. Rather than shutting it down, leaning in is probably the smarter long-term move.

(To their credit: the Nigerian government has been engaging stakeholders from founders to investors and bankers to revise its position. Let’s see what happens.)

Regulators’ distrust of investing isn’t limited to crypto. Regular old equities aka Boring Crypto, also received their fair share of ire. In April, Nigeria’s SEC issued a terse statement instructing personal trading platforms like Bamboo, Trove, Rise, and Chaka to stop allowing the purchase of foreign securities not listed on exchanges registered domestically. Though these platforms aren’t doing anything illegal, it was a way for regulators to gum up their wheels and buy time.

If the two examples above were limited to the digital world, the next had direct, physical consequences for citizens. At the start of 2020, Lagos’s state regulators decided to ban the use of commercial motorcycle taxis, stranding passengers across the city and crushing on-demand platforms like Okada, Pride, Gokada, and Keke.

For lesser entrepreneurs, this might have been a killing blow — a testament to the ingenuity of the founders is that some successfully pivoted. Gokada, for example, reacted to the ban by moving into delivery, allowing them to continue partial utilization of their fleet.

Finally, in early June, the Nigerian government banned Twitter...on Twitter. Quite a power move. Thirty-nine million national users were locked out of their accounts.

While machinations like this often look like old men grasping at straws, there are signs that African governments are progressing. Pre-pandemic, no bureaucrat would have dared to take a virtual meeting. Now, many use Zoom. Meanwhile, the government of Rwanda has renovated its communication with citizens via Irembo, a “one-stop” digital portal for public services that powers over 100 agencies and parastatals.

These are relatively small blessings, but hopefully others follow suit.

Waiting on regulators

In the musical, 1776, covering the American Revolution, John Adam says:

I have come to the conclusion that one useless man is a disgrace, that two become a law firm, and that three or more become a congress.

Government’s are not usually known for their speed, and African countries are particularly hampered by operational lassitude. As mentioned, they’re also marked by a degree of cronyism — to get something done; you may need to know someone on the inside.

In Nigeria, for example, if you wished to found a fintech platform in the savings space, you might be forced to wait several years to receive governmental permission, spending millions of dollars in the process. We’ve seen insurtech startups try for upwards of four years to get regulatory sign-off. Even though they had mature platforms, these companies still couldn’t get the requisite paperwork.

To succeed, then, founders have to gamble. Rather than waiting, entrepreneurs partner with commercial institutions like banks, leveraging their regulatory cover to build. The implicit wager made is that the startup can accumulate enough traction, money, and influence under-the-radar before regulators demand they get further licenses.

You see this play in fintech most often. African neobanks get off the ground by securing a “super agent license” and other support from partner banks. Typically, it’s only after raising capital that these startups attain a standalone “microfinance bank” license, granting broader ability to operate.

The lesson? For entrepreneurs and investors in Africa, eight times out of ten, it’s better to beg forgiveness than ask permission.

Regulatory capture

As countries develop, the number of industries that meaningfully contribute to the economy tends to increase, resulting in a more democratic representation of power. Before that point, however, power structures are often oligarchic, with leaders from dominant sectors wielding outsized influence. This is the case across much of Africa.

Let’s use fintech as an example, again. Despite attracting considerable attention and investment, fintech businesses nevertheless have to navigate traditional stakeholders.

In East Africa, telecommunications firms hold much of the power. (Remember what we said about MNOs?)

Safaricom’s M-Pesa mobile money network processes more than half of Kenya’s GDP. Oh, and the company is partially owned by the government, which holds a 35% stake. This is wild, almost as if America’s government owned a third of some ungodly AT&T-PayPal chimera. What kind of power would that hybrid possess?

MTN Group has similar, though less formalized power in neighboring Uganda, processing 80% of the $20B that flows via mobile. To create a fintech business in either country requires not only entrepreneurial skill but political savvy.

In West Africa, traditional banks are king. These institutions have long-standing relationships with governments tied to exports and currency policy. In a Godzilla versus Kong dynamic, these entities are so powerful they can even thwart other titanic businesses.

MTN Group is one of the largest financial businesses on the continent. And yet, it cannot operate a payments network in Nigeria.

Why?

Because local banks don’t want that to happen. They’ve fiercely resisted the incursion and levied their governmental influence to keep MTN out. If corporations like MTN find their ambitions curbed, it’s easy to imagine the sway such stakeholders have over the fate of startups.

Managing Expansion

Something American investors rarely have to think about is national expansion. A company that succeeds in the US is plenty big. That makes extension beyond domestic borders a secondary concern. Companies in India and China may have the same luxury, but in much of the world, national expansion is a strategic concern from day 1.

Most African markets are not large enough to sustain venture-sized businesses. (This is, by the way, the counter to our little diatribe about funding differences between the US and African nations.) That requires founders to have a broader mindset and lock in a coherent expansion narrative.

In the section below, we’ll talk about the single markets, some common maneuvers companies use to grow, infrastructural limitations, and common expansion mistakes.

Single markets

In The Generalist’s coverage of Nubank and Mercado Libre, we discussed how tricky Latin American companies find the transition from a single market to continental dominance. Differences in language, regulatory bodies, and cultural norms mean that running a neobank in São Paulo is very different from doing so in Mexico City.

Africa is this, multiplied by 100x. (Or more).

As we’ve shared, there are many countries, languages, nationalities, and cultures. Furthermore, a lack of data on different markets makes strategizing a market opening even harder.

Because of that, investors tend to exhibit a bias towards startups with a large home market. A survey of 30 African startups conducted by Sherpa Ventures illustrated that companies in South Africa and Nigeria were almost twice as likely to raise capital without additional operational markets compared to similar entities in Ghana and Rwanda.

Earlier, we talked about the countries that monopolize venture investment: Nigeria, Kenya, Egypt, and South Africa. The same quartet are best able to support a single market strategy, with Nigeria the most obvious example for the reasons described earlier. But even companies from these nations often have to position themselves as attacking a broader area.

For example, Egyptian decks usually position the home market as a launching point into other parts of North Africa and the Gulf. It’s much less common, for example, to see Egyptian companies present a plan to extend southwards into Nigeria, South Africa, and Kenya. This is likely because of the significant differences between the Egyptian market and Sub-Saharan Africa. Similarly, Kenyan startups often look to loop in Uganda, Tanzania, and Rwanda as they grow.

Trying to move in the opposite direction is much harder. Founders launching from smaller markets like Uganda (44 million people) or Rwanda (13 million) face an uphill battle (😉). Their home markets are usually too small to bear a venture play, and localization into larger markets means competing with Nigerians in Nigeria, Kenyans in Kenya, and so forth. We’ve seen exceptions — notably, Chipper Cash, which started in Uganda — but these are dwarfed in number by those that have struggled to break out.

Customer-led

According to Sherpa’s study, companies usually expand to increase revenue. Seventy-nine percent of surveyed entrepreneurs noted that generating more cash was the primary driver of expansion, with diversification second. (This is interesting so much as investors are often looking for diversification, first.)

If revenue is the goal, it’s logical that many startups expand by following their customers. This is particularly the case with B2B startups. Companies that are lucky enough to have large corporates as clients derisk expansion by serving the same company in new locales. These multinationals ensure some revenue comes through the door and serve as a vital educator and facilitator.

One startup that has leveraged this approach is Lori. An e-logistics business offering trucking services, Lori counted the World Food Programme as an anchor customer in Kenya. The Timon Capital-backed company recognized that it could extend that relationship if it operated in Uganda and South Sudan. The company seized the opportunity and entered both markets.

Available infrastructure

Of course, expansion is constrained by available infrastructure. Budding fintech companies often build on the back of payment providers like Paystack and Flutterwave. If those products aren’t available, it’s orders of magnitude harder to launch.

Other companies rely on modern mobile money providers. Bboxx, a solar energy business, needs to collect payment for its services. Without the necessary infrastructure, operationalizing cash collection would be untenable. This might all sound like it's a little in the weeds, but the upshot is that even companies unrelated to fintech find their path determined by core providers.

Failed expansion

Moving into a new market doesn’t always pay off. Sherpa’s survey found that 13% of companies had to shut down a secondary market, with the biggest challenges identified as navigating regulations and hiring local talent. Remarkably, one out of three startups move into a market without making any local hires; either by choice or necessity.

Other factors that influence the success of an expansion are timing and competition.

Of those surveyed, more than 50% noted that they had chosen to launch a new market within their first two years of operation, a rather quick clip. It’s easy to understand why this is the case, given the desire to de-risk (and earn more cheddar). But many do so before they have achieved product-market fit in their first geography.

Moving into a new market also means engaging with competitors that may have the context and connections to outmaneuver larger interlopers. Rwandan companies start by building for the Rwandan reality. The same is true in Egypt, Kenya, and South Africa. These are very different places. As one analyst recalls:

My first trip to Africa was to AfricaCom, a large telco-centric conference in Cape Town...while there, I had several South Africans ask me, “so are you planning to visit Africa on this trip?”

Questions like this reveal the immense cultural and racial divides — both overt and implicit — that separate geographies. That native knowledge can create enduring defensibility.

Stay one step ahead of the most important trends shaping the future. Our work is designed to help you think better and capitalize on change.

Foreign Capital

Venture capital used to be a localized trade. Silicon Valley became a technical hub because people like Arthur Rock identified and backed talent in the region. Those that did well, often went on to do the same, who went on to do the same, who went on to do the same, ad (almost) infinitum.

The last two decades have seen a shift away from this model as investors have learned to evaluate target companies and provide post-investment advice remotely. Covid has turbocharged this trend, underlining that the range of one’s Tesla’s probably isn’t the most useful way to circumscribe an investment territory. More investors recognize great companies are being built everywhere, but capital is unequally distributed.

That’s sparked a surge of interest in African tech. Foreign investors first started sniffing around the ecosystem in 2015, but the last year has seen a jarring shift. You now hear Patagonia-vested types talk about their fund’s “Africa strategy” on Sand Hill Road.

To understand this movement and its roots, we’ll dig into four categories of foreign capital:

Opportunistic capital

Impact capital

Policy capital

Soft-power capital

We’ll also touch on the government’s role in attracting financing.

Opportunistic Capital

Institutional quality venture funds (both local and foreign) began to hone in on Africa in 2016. These investors were fundamentally opportunistic, moving into markets they found promising without additional motivation. This coincided with YC and 500 Startups accepting an increasing number of African startups into their programs.

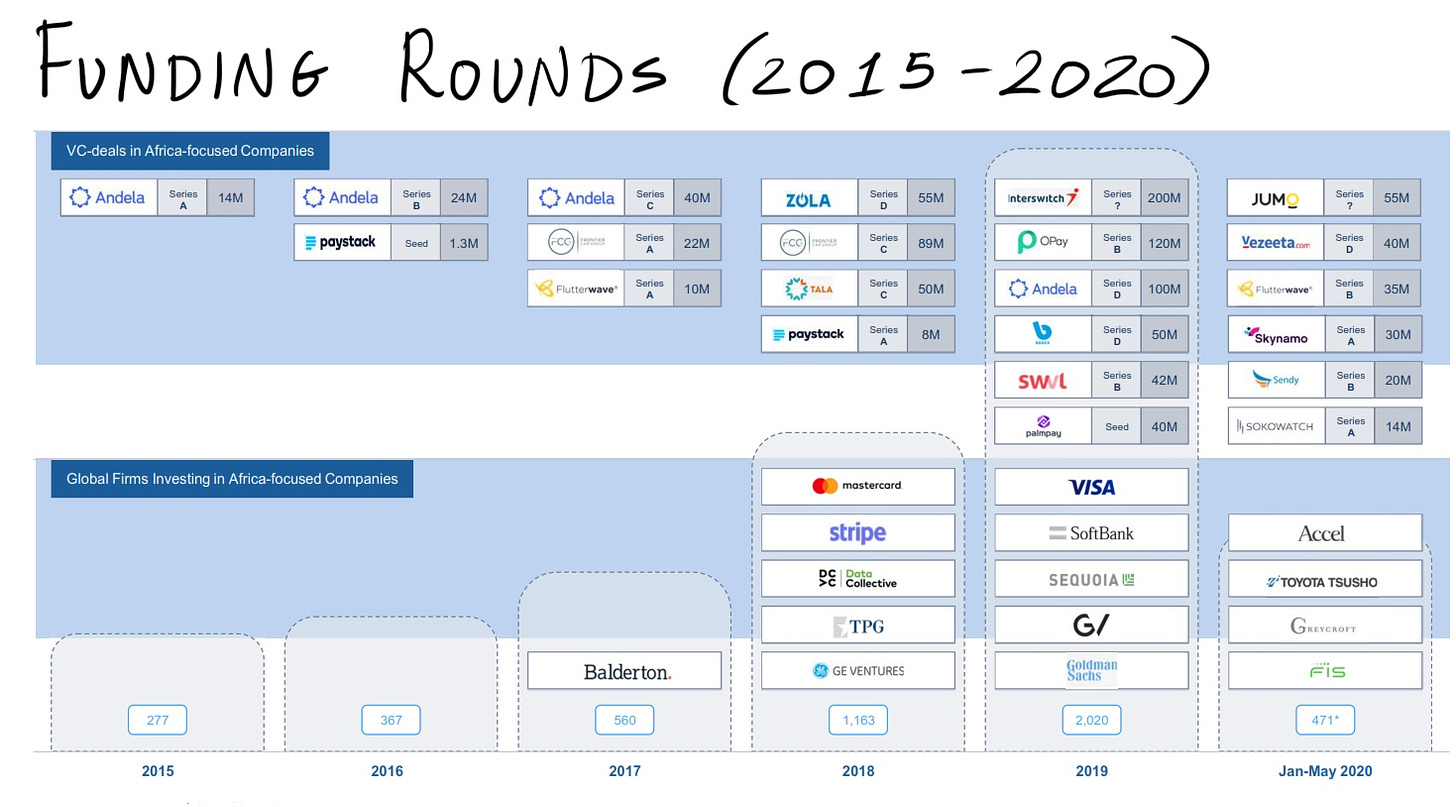

That interest has shown no signs of abating. Since then, TPG, Softbank, GV, Greycroft, and Sequoia have all shown an interest in the geography, and investment in Africa has grown 6x since 2017. The chart below illustrates this proliferation on a deal-by-deal basis.

Policy Capital

If opportunistic funds are the newcomers, policy capitalists are old hat. Historically, financial institutions tied to development have been the most conspicuous private-sector backers. This is true across emerging markets but is especially so in Africa.

Key players include the International Finance Corporation (IFC), a sister of the World Bank. Associated organizations include the UK’s CDC Group and France’s Proparco. These entities have traditionally represented between 50-70% of the LP base for private equity and venture capital funds in emerging markets.

As the market has begun to heat up, these institutions have followed the playbook of other large capital allocators, moving down the stack. Though they’re late to the party (and on another timescale, extremely early), they’ve begun to look at VC as an asset class worthy of direct focus. Now piqued, we expect this interest to grow.

Impact Capital

Impact investing aims to invest in socially responsible investments, which promote social good and generate revenue. Africa has become a major recipient.

The adoption of the Sustainable Development Goals has guided conversations around impact investing, acting as a framework. According to a survey from the Global Impact Investing Network (GIIN), 59% of impact investors have assets allocated in emerging markets, with most capital (21%) targeting Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA). Further, 52% of these investors are looking to grow their allocations to SSA over the next five years. This cohort may prove critical in fortifying the ecosystem, investing in business propositions that don’t appeal to opportunistic capitalists but may serve a critical purpose.

Soft-Power

Much has been made about China’s desire to access and control foreign markets asymmetrically. In Africa, the CCP wants to grab resources and dictate standards so that it might better dominate industries built on top of them, from fintech to social media. This is, in effect, soft power manifested via investing.

While many have heard about the Belt and Road initiative (BRI), in 2015, China began to discuss the Digital Silk Road (DSR) openly. DSR funding has mainly gone towards infrastructure investments in IT, communications, artificial intelligence, cloud computing, mobile payment systems, and surveillance technology via companies like Huawei.

(Who built 70% of Africa’s 4G network? Huawei.)

China already provides more financing for African IT and communications than all multilateral agencies and leading democracies combined.

China has always been an important partner to Africa, serving as the continent’s largest trading partner for ten consecutive years. In 2019, trade between China and Africa recorded $204.2 billion, up 20% from the year prior. The same year saw more than 3,700 Chinese enterprises operating in Africa, total Chinese investments of $46 billion, and more than 1 million Chinese people living on the continent. China sees Africa as a critical ally and key geography.

Beijing’s interest has been accelerated by its deteriorating relationship with the US. The trade war between the two countries and America’s rising anti-China sentiment made it more attractive to invest in Africa, rather than fight the uphill battle of deploying in the States or its allies. This froideur has, of course, arrived at a time of burgeoning wealth in China; in 2017, the BBC reported the country was creating two new billionaires a week, while in 2021, Beijing became the city with the highest number of billionaires in the world.

African tech has profited.

Starting in 2015, Tencent has invested in a number of African tech startups including Flutterwave, Paystack, and Helium Health. Beginning in 2019, Chinese VCs joined the party. PalmPay, OPay and Lori Systems collectively raised $248.7 million from different Chinese investors including Hillhouse Capital, Crystal Stream, Transsion, Meituan-Dianping and Sequoia China. Staking further claim, Transsion Holdings — a Chinese company that produces ~43% of the smartphones sold across the African continent — founded Future Hub, an incubator and accelerator backing African startups.

Interestingly, Chinese investors tend to take a different approach from US ones, in our experience. Rather than taking a minority share and sitting back (comparatively speaking), Chinese VCs often want to play a significant role in running the business. Sometimes that means taking an entire round or setting up a new entity from scratch.

This is another mark of a soft power approach; control is paramount. Forfeiting this control carries risks for the domestic ecosystem. OPay provides one example of how this can play out.

A subsidiary of Opera, a Norweigan browser company owned by Chinese investors, OPay has received significant financing from Chinese financiers, including Meituan-Dianping, GaoRong, and Sequoia China. While local competitors like Paga, Crowdforce, and Bankly have grown their fintech footprint steadily over years of hard work, OPay has expanded rapidly, using its hundreds of millions in funding. The result is that a critical part of the mobile internet space — mobile money — is accruing to a foreign entity that is disrupting endemic players. Unlike the rush they showed to shut down Twitter, Nigerian regulators have acted slowly, providing little protection. They’ve limited access to some licenses and forced collaboration with domestic players, but have otherwise sat back.

Will a more protectionist bent emerge over time?

India, another popular destination for Chinese capital, offers an interesting example. Since 2016, Chinese investments have increased 12x, with 18 out of 30 Indian unicorns registering Chinese entities on their cap tables.

While this foreign money almost certainly aided the ecosystem’s maturation, the Indian government has grown savvy to its perils. New regulation seeks to limit Chinese investors’ control in Indian companies; last summer saw 59 Chinese apps banned with authorities citing national security concerns. Though such interventions are somewhat geopolitically motivated, they’re also reasonable — a report from the Indian Council on Global Relations found that Chinese companies and VCs look to gather data from Indian companies to further the Chinese government’s agenda.

Only time will tell what China’s Africa legacy will be. We hope that President Xi Jinping’s comments from a 2015 summit prove sincere:

China-Africa relations have today reached a stage of growth unmatched in history. We should scale the heights, look afar and take bold steps. Let us join hands, pool the vision and strength of the 2.4 billion Chinese and Africans, and open a new era of China-Africa win-win cooperation and common development.

Creating Startup Nations

Beyond providing protection, governments have an essential role to play in attracting foreign capital and catalyzing the local VC industry.

Perhaps no country has been more successful at building a “Start-up Nation” than Israel. That triumph brings its own challenges. For instance, Israeli companies are disproportionately involved in acquisitions or mergers. As a result, local entrepreneurial talent often moves abroad, adversely affecting local employment and economic growth. This is the opposite of what local ecosystems need: the recycling of expertise from successful founders to insurgent entrepreneurs. Both the Canadian and Israeli governments have specifically enacted programs and policies to counteract this adverse effect.

African governments have a long way to go before they approach the efficacy of Israel’s entrepreneurial policies, but there are promising signs. In 2018, Tunisia passed a “startup act” designed to encourage entrepreneurship. This policy clarified investing standards, subsidized entrepreneurs’ salaries, and provided tax benefits to designated companies. Since its passage, Senegal has followed suit, while Ghana, Mali, and other countries consider versions of their own.

Ultimately, Africa will need many capital sources to fund its next age of growth. The continent faces a multibillion-dollar infrastructure gap that will only be fixed with a combination of homegrown brilliance and both local and foreign financing. What entrepreneurs will have to recognize is that different sources of capital come with differing conditions. Many will hope governments and citizens can work together to forge mutually beneficial frameworks, rather than founders surrendering control of their data and infrastructure to foreign entities.

Misconceptions

For a long time, investing in African tech was seen as a rather unusual vocation. As foreign investment in Africa has increased, an increasing number of traditional VCs have reached out to the analysts on this piece to understand the market. While it’s encouraging to see growing enthusiasm, newcomers reasonably enter the space with distorted views. In particular, we find these three misconceptions to be most prominent:

Misconception 1: Africa is a unified market

Misconception 2: All the startups are “X for Africa”

Misconception 3: You can use the same multiples to value African startups

Let’s do some debunking.

Africa is not a unified market

Analysts on this piece recently came across an investment memo for a large African fintech, written by a prominent Silicon Valley firm. While the analysis had merit, there was a clear shibboleth: the report’s writer equated India’s population to Africa’s.

Anyone with knowledge about African tech knows this is a dead giveaway. Superficially, yes, India’s population (1.4 billion) and Africa’s (1.3 billion) are comparable. But there are critical differences, not least the presence of Unified Payment Interface, demonetization policies, and per capita income trends.

More than any of these specific discrepancies is the fundamentally flawed comparison between a country and a region. As we hope we’ve hammered home already, Africa is a highly fragmented, diverse continent. While India certainly has extraordinary cultural and linguistic diversity, there’s nevertheless a meaningful difference between a landmass of 54 distinct nations and a family of federated states.

Trying to use India or China as an analogy misses the reality of investing in Africa: it’s not a unified market, it’s a region. Companies do not operate “across Africa,” they win share in specific national markets. Trying to extrapolate trends for consumer app adoption across the continent based on either country will necessarily represent a dangerous conflation.

Of course, it’s understandable that many begin with this kind of framing, particularly if they have more experience in other regions. It doesn’t help that venture investors are also seduced by large total addressable markets (TAM) and knowing that, founders craft continental fairytales to inflate the size of their opportunity. Rather than positioning themselves as a “Rwandan fintech,” startups often frame themselves as pan-African.

The result is a disconnect: VCs think they’re investing in a company chasing a huge TAM, when the reality is usually much more modest.

One of the analysts on this piece recently caught up with an established fintech founder. The entrepreneur has raised more than $10 million in funding for a Nigerian venture. In conversation, the founder noted that “we raised on the idea that our TAM was 200 million people...but three years in, we figure it’s closer to 4 million.”

If TAM math can become this distorted even within a single country, how muddled might it become when extrapolated across the continent?

It’s worth noting that while African founders may tell a tale of transcontinental TAMs, foreign founders often spin even more expansive stories. This is a double-standard. Branch and Tala, run by US CEOs and backed by US VCs, started in East Africa and told a global story from day one. African founders, meanwhile, are often met with skepticism when they discuss moving into Mexico, Pakistan, or other large emerging economies.

Of course, this doesn’t make executing such a playbook any easier, whether by foreign or local founders. Branch and Tala have largely struggled to localize their credit scoring model to new, non-M-Pesa markets. FlexClub (South Africa to Mexico), Migo (Nigeria to Brazil), Paga (Nigeria to Mexico), Jumo (South Africa to Pakistan) have faced similar issues.

The irony here is that the category of error between investors and founders discussed above is the same: over-generalization. Just as entrepreneurs discover the demand for their product may not extend across emerging markets, VCs must note that the businesses they look at from one market can’t be easily compared to those in Africa, and that most will remain regional, rather than extending from sea to sea.

A good rule of thumb for investing in Africa: never trust the TAM.

Africa has a unique ecosystem

As discussed in a previous piece, Sequoia decided to pull out of Brazil in 2013 because the firm found that the preponderance of startups was essentially “X for Latin America.” That lack of creativity was taken as a sign of an immature tech ecosystem.

Many hold similar opinions of African companies today, but it's a misconception. Though startups on the continent have been influenced by both Eastern and Western counterparts, there’s an endemic movement to build the necessary infrastructure that feels divorced from venture “trends.” Broadly speaking, the ecosystem has developed in three waves.

The first wave saw African startups enter e-commerce, emulating businesses like Amazon. These companies modified themselves to suit the local environment, but in many cases, the demands of that environment broke the business model — payment rails and financial access weren’t there; customers were used to paying upon delivery; logistical infrastructure was weak.

This era, spurred on by the caricature capital of Rocket Internet, resulted in creating facsimiles for Booking, Amazon, Carvana, and other Western businesses. As characterized by Derin Adebayo in an excellent piece, this age can be summed up by the strategy of, “Hey, let’s throw a .ng onto successful .coms.”

The second wave saw entrepreneurs draw inspiration from Asia. Winning startups from the region had succeeded despite inadequate infrastructure and lower discretionary income levels—challenges that African companies faced. Many flourished by providing a high-frequency product (messaging or payments) and then layering on higher-value services (e-commerce, lending, investments). This super-app playbook is the same one that propelled Gojek, Grab, and many others into the limelight. As mentioned earlier, companies like OPay have been executing this approach in Africa. There may still be considerable room left to run here.

We have entered a third wave. Rather than modeling itself on other ecosystems, an increasing proportion of African startups seek to respond to the realities and requirements of local environments. The companies are building market-enabling technologies that allow companies to create consumption out of non-consumption and reorganize patterns of economic behavior. In many cases, that manifests in infrastructural plays like Flutterwave, Paystack, Paymob, MFS Africa, and DPO.

You can also see it more subtly in businesses like Sokowatch. The platform provides financing to informal retailers — basically helping small stores access credit. To do that, the company has built out a 1PL logistical network that delivers merchandise. Then, using the store’s purchasing history on the platform, Sokowatch can reliably supply merchant credit. Fascinatingly, this credit is often supplied in the form of goods, not money. That’s the kind of play that works in Africa but likely wouldn’t in many other geographies.

We seem to be at the beginning of a larger trend here, with more entrepreneurs building B2B APIs that will power succeeding generations. In addition to the payment processors above, we see the emergence of APIs for communications (Termii) and unified financial data (Pngme, Mono, Stitch). While it’s tempting to refer to Termii as “Twilio for Africa '' or Mono as “Plaid for Africa,” that would be a disservice to the organic, bottoms-up innovation happening, distinct from the parachute-in process of Rocket.

Of course, there’s plenty of infrastructure still to build, with much more robust tech needed in the cash-in/-out (CICO), eKYC, fraud management spaces. It is the position of some of the investors that contributed to this piece that API architectural plays will prove particularly exciting, offering the clearest pathway to exit as well as providing a data-rich view of local fintech.

Though they’ve succeeded in raising richly, the age of durable consumer app winners may have to wait.

Valuation is different

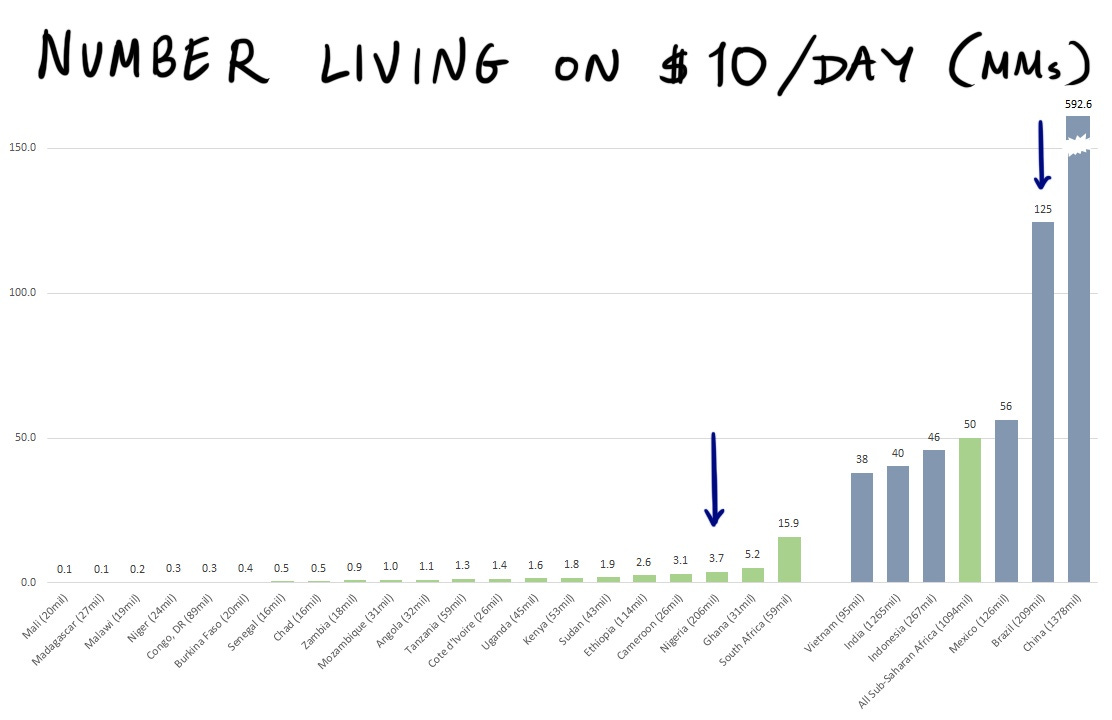

For the most part, valuing startups based in Africa requires foreign investors to recalibrate their expectations. The economic realities are that there are many fewer African consumers with meaningful discretionary income. For example, even though Nigeria (206 million) and Brazil (209 million) have similar-sized total populations, there are ~34x more Brazilians spending more than $10 per day.

This means that some of the fundamental math doesn’t work the same way in Africa as it might in other geographies. Assumptions that might seem reasonable to make around LTV and CAC are often wildly offbase.

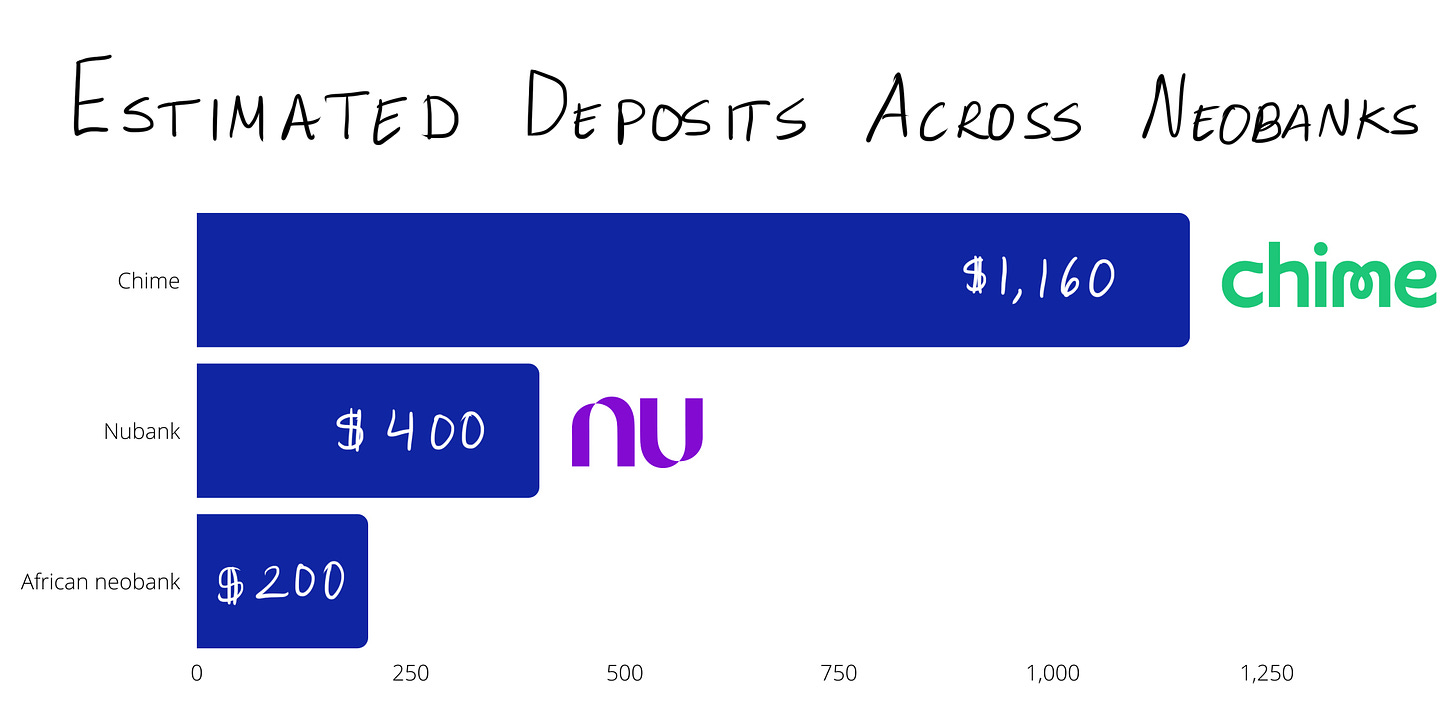

Let’s take the example of neobanks. Market leaders in Africa often see considerably lower deposits per customer than elsewhere in the world. In our experience, the average customer of an African neobank puts ~$200 onto the platform.

By comparison, data from 2019 indicates that US platforms like Chime see deposits of roughly $1,160 per user. Some back-of-the-envelope math on Nubank suggests the company likely sees deposits in the $350-$400 per customer.

Western investors may have preconceived notions that a business model they know in other geographies will see the valuation multiple expand a certain way as the company scales. They might not factor in the quality of the current revenue or do the work to understand it. For example, the company in question may be generating significant cash based on discrepancies between official exchange rates and actual market rates; but those may be likely to get adjusted or competed out over time.

Yet, African deals are being valued at all-time highs. Investors seem increasingly willing to back up their cash trucks to compete with the giant coffers and the existing distribution of incumbent banks and telcos. Often these deals value African neobanks as if customers store similar assets as in other geographies.

This capital influx benefits consumers, with venture dollars subsidizing payments, top-ups, bill pays, and credit, but inflates CAC, too. As acquisition costs increase, will churn and LTV keep pace?

Fundamentally, many foreign financiers value startups in African countries in a manner disconnected from the TAM and CAC: LTV truth. (Arguably, this is an issue plaguing the global asset class, even if it appears particularly severe in Africa). Over time, we hope a more detailed method of appraisal wins out.

Opportunities

Africa is home to some of the biggest challenges. However, as the past decade has shown, these also represent tangible opportunities. From education to SMEs, healthcare to fintech, Africa needs radical and innovative solutions to its biggest problems.

Education

There is a huge opportunity to leverage scalable technology and offer affordable education across Africa.

Across the continent, classrooms are overcrowded, and since Covid, schools in much of SSA have closed to stop its spread. Workarounds proposed by governments like schooling via TV and radio are inadequate replacements for in-person classes. Other alternatives, including online courses, have a limited scale due to the lack of access to the internet discussed earlier.

Because of the demographic trends we cited, Africa desperately needs a better education system. By 2050, Africa will be the only region globally with a growing working-age population, but a large cluster of African countries don’t have the capabilities to train this influx. Many teachers don't have the training or qualifications needed to deliver quality education — 85% of primary school teachers globally have been adequately trained; in SSA it's just 64%.