The Future of Solo Capitalists

Solitary general partners now manage more than many multi-person venture funds. What are the limits of a one-man band? And how should legacy firms counter?

In collaboration with Clay...

I’ve known the Clay team since the beginning, and I’m hyped to share more of their story with you soon. Clay brings data sources together to help people find information and build (sometimes mind-blowing) automations. It’s pretty cool to see how companies are using Clay to superpower their growth, sales and recruiting teams. Here are a few neat examples:

Growth: You can stream in email signups from Hubspot, add data from LinkedIn (things like title, company, etc.), and see if those companies are hiring for certain jobs or what their tech stack looks like.

Sales: You could start by searching LinkedIn, add emails and phone numbers from sources like Clearbit, and sync back to your CRM or marketing platform.

Recruiting: I didn’t know recruiting was this high-tech these days, but apparently you can stream in Twitter followers (or even threads and DMs!) and Github stargazers to a table, filter the bios for keywords like engineer or iOS, match to LinkedIn profiles, and then connect to Lever or your email client.

If you’d like to join me and companies like Mainstreet, Pave and Newfront — click this Generalist link to get a month on the Pro plan for free. And check them out on Product Hunt this Tuesday!

Actionable insights

If you only have a couple of minutes to spare, here's what investors, operators, and founders should know about solo capitalists.

Leading “solo capitalists” manage more money than many funds. Oren Zeev manages more than $1 billion without additional investment support. Elad Gil, Josh Buckley, Harry Stebbings and Lachy Groom manage funds in the hundreds of millions with similarly lean structures.

They win through speed, empathy, and expertise. By avoiding firm politics, solo investors can move more quickly, committing to a round in hours or days. Many are current or previous operators, giving them empathy for founders’ journeys. Some bring unique expertise to the table, too.

Creators lead the way. Many members of this movement built their reputation as creators, amassing large audiences in the process. This influence has been translated into securing allocation in competitive rounds. Those that tell powerful stories about their portfolio businesses can drive remarkable results.

Established institutional LPs have backed solo GPs. University endowments and other institutional investors have funded several top managers. In doing so, these LPs seem to have made peace with the model’s structural risks.

Venture firms should aggressively ally with these disruptors. While tier 1 funds will worry more about Tiger Global, solo investors have changed the market’s dynamics. Proactive firms will adapt, empowering these managers and benefiting from their favorable brand and impressive reach.

Learn how the best businesses and investors win. Every Sunday, we send a free email that explains the business world’s most important innovations and the stories behind them. It’s high quality business analysis, delivered at no cost to you.

There is only one place to begin. On Thursday of this week, TechCrunch reporter Natasha Mascarenhas tweeted a link to an SEC filing. The Form D noted that Buckley Ventures III, LP intended to raise a $500 million investment vehicle.

If you’ve never heard of the fund before, that news might not mean much. Venture firms seem to be raising at an unprecedented clip with Kleiner Perkins, Andreessen Horowitz, and Paradigm all announcing mega-funds in 2022.

The difference is that Buckley Ventures is managed by a single individual: Joshua Buckley. Not only is the sole general partner (GP), on track to manage more money than many partnerships, he also serves as the co-founder of Prologue, a holding company that manages Product Hunt and its affiliated accelerator, Hyper. In this breadth, Buckley is an unusual case. But he is not alone in managing considerable capital as a solitary fund manager.

As brilliantly articulated by Nikhil Basu Trivedi in his canonical piece, “The Rise of the Solo Capitalists,” a new wave of investors has emerged that manage large capital bases and win allocation over storied funds. Conventional wisdom suggests that these solitary operators succeed primarily by better empathizing with founders and moving more quickly – venture capital’s nimble, darting speed boats carving circles around incumbents’ slow-moving frigates.

Since he published his piece 18 months ago, the trends Basu Trivedi observed have accelerated. Players like Josh Buckley, Oren Zeev, Brianne Kimmel, Lachy Groom, Shruti Gandhi, and Elad Gil are managing significantly more money, while newcomers like Packy McCormick and Harry Stebbings have translated large, engaged audiences into fresh venture vehicles. Many others are quietly thriving and insurgents are bubbling up behind this emergent class.

What should we make of this movement and where is it headed? In today’s piece, we’ll attempt to answer these questions, while digging deeper into the following topics:

Definitions. Basu Trivedi offered a concise definition of “solo capitalists.” Since his piece, its meaning has taken on a life of its own.

Catalysts. Though Silicon Valley has always had its angels, societal and sectoral shifts have galvanized this cohort.

Players. Some institutional managers have begun aggressively seeding solo GPs. We’ll talk through who provides the firepower and where it ends up.

Playbooks. With fewer resources and less time, solo investors should theoretically struggle. Instead, they’re thriving.

Challenges. Playing the solo investor game isn’t easy. The model’s strengths come with drawbacks and some of the cadre’s allure may not last forever.

Countermoves. Top-tier funds won’t be overly worried – at least for now. Marginal players, however, are seeing allocations move elsewhere. To survive, they must adapt.

Let’s go solo.

A definition

In Basu Trivedi’s article, he highlighted five characteristics that define the solo capitalist, printed below:

They are the sole general partner (GP) of their funds.

The solo capitalist is the only member of the investment team.

The brand of the fund = the brand of the individual.

They are typically raising larger funds and writing larger checks than super angels - i.e. $50M+ funds, and able to invest $5M+ in rounds.

They are competing to lead Seed, Series A, and later stage rounds, against traditional venture capital firms.

Perhaps as a consequence of its cultural impact, the term seems to be more liberally used today. Rather than referring only to those leading deals and managing funds larger than $50 million, the “solo capitalist” characterization is often loaned to investors we might once have considered “solo GPs” or, “super angels.” When I asked who the best representations of the “solo capitalist” movement were on Twitter, I received a range of responses – angels intermingling with fund and syndicate managers.

Twitter is not the place to look for a definitive definition but it gives a sense of how those in tech think of the phrase. In common parlance, it seems to have moved from species to genus, referring to a collection of differently complected participants.

As Andreas Klinger, founder of Remote First Capital, remarked, “Angels and solo capitalists are blending into each other… I think of them as the same thing unless they have a large team somehow.”

In researching this piece, I got to connect with many that are a part of this movement. I found there to be a dizzying range of strategies and structures at play, as well as plenty of common ground. For clarity’s sake, we’ll favor the term “solo investor” when speaking of the general movement, saving the “solo capitalist” moniker for those that meet the five characteristics Basu Trivedi identified. We’ll also attempt to differentiate this group with “solo GPs” and “super angels” while avoiding a semantic morass.

The emergence

If Silicon Valley has an “unmoved mover” it is Arthur Rock. As described in an earlier piece, the man that financed Fairchild Semiconductor, Intel and Apple operated for much of his career as a lone wolf, a proto-solo capitalist. The existence of such investors is not new, then, but the last few years have elevated their presence.

What explains the rise of the solo investor? A handful of factors seem particularly critical, though it’s worth noting that no trend of such altitude operates discreetly. Rather, they mingle, influencing each other. Here are the five I find most critical:

Individuals can amass distribution power directly.

Venture capital has grown as an asset class.

Knowledge has formalized and best practices have emerged.

Tech and investing have hit the mainstream.

Infrastructure has made going solo simpler.

Shift 1: Individuals can amass distribution power

The advent of social media disrupted the creative supply chain, displacing traditional tastemakers. Rather than needing to have a story accepted by one’s local paper to get a certain message out, individuals were free to publish their thoughts online.

This movement was not limited only to social media, of course. Internet platforms have enabled blogs, newsletters, podcasts, and other creative endeavors to flourish. Each of these activities can attract significant audiences.

Of course, a consequence of this shift is that individuals became media companies, presented at the same level as legacy publishers. In a flattened information stream, the most active and successful built large followings and earned consumer trust. In and of itself, this redistributed power. While much of it went to the platforms enabling this behavior, individual creators benefited, too.

Many solo GPs have emerged from this shift. Creators like Packy McCormick, Lenny Rachitsky, Nik Milanović, Turner Novak, and Harry Stebbings use large audiences to secure allocations into competitive funding rounds. Once these creators establish an ability to secure unique access, it’s natural to raise a fund to execute that strategy with orders of magnitude more capital than an individual can personally deploy.

Shift 2: Venture capital has grown as an asset class

In 2012, venture capitalists invested roughly $60 billion. In 2021, that figure reached $643 billion. From 2020 to 2021, the amount of money deployed by the asset class nearly doubled, increasing by 92%.

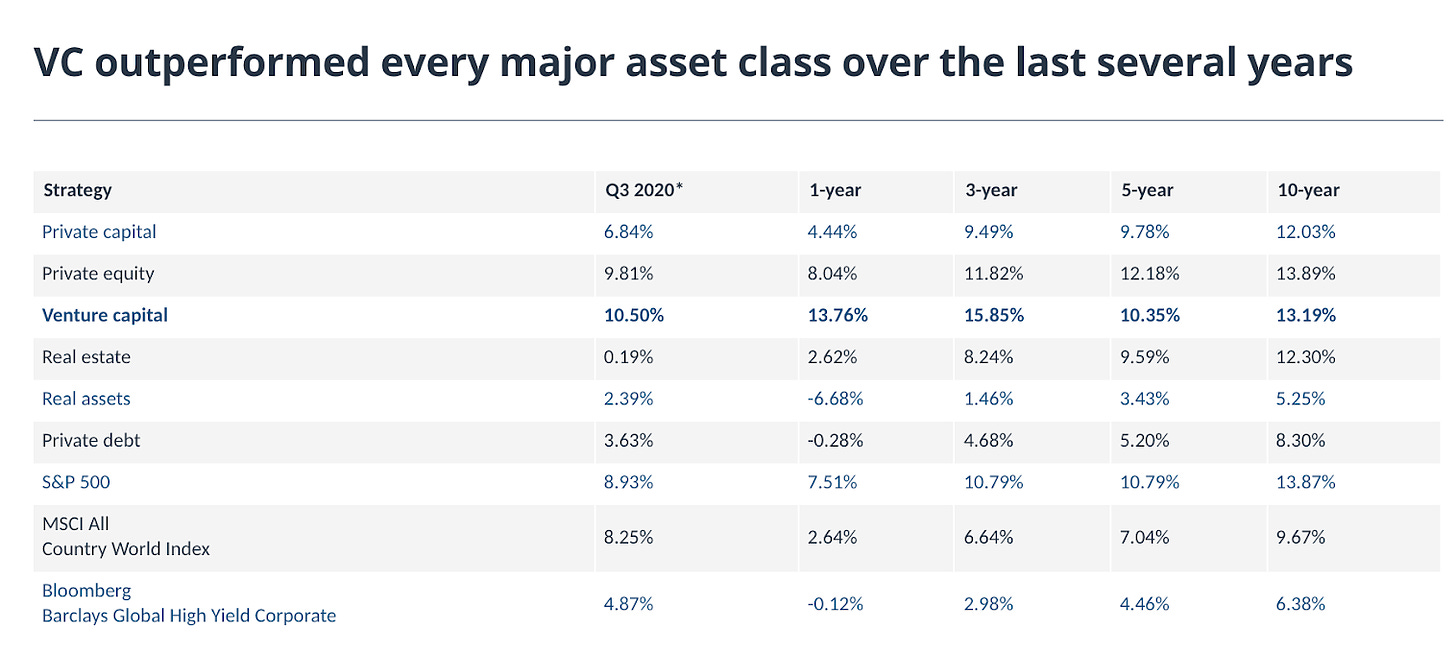

Such an increase has been merited by venture capital’s performance in recent years. According to Pitchbook, in the three years prior to 2021, venture outperformed every major asset class with 15.85% annual returns.

Such figures have tempted limited partners (LPs) to increase their allocation to existing funds and dabble in newer vehicles. The latter can be both a strategic choice and a necessity. For one thing, emerging managers often outperform established ones. Perhaps more importantly, marquee funds are oversaturated. GPs of large firms have noted they are often unable to put as much capital to work as an LP might want. New investors, even if operating solo, benefit by giving these LPs a place to deploy.

While the proliferation of capital has helped put many solo GPs into business, it has also tilted the board in their favor. Speed matters much more now. Whereas in previous eras, venture capitalists could afford to take weeks or longer to get to know a management team, today’s allocators need to move faster, sometimes in a matter of hours.

Few traditional funds are set up for this cadence. Considerable research may be necessary to reach conviction and investment committee meetings are often held once a week. By the time a decision has been made, the opportunity may be gone.

By contrast, solo GPs thrive in this blitz-version of the game. When speed becomes a primary variable, the single decision maker has an advantage. These new dynamics have helped individual investors win access to competitive rounds, raising their status and attracting further capital.

Shift 3: Knowledge has formalized and best practices have emerged

It is never easy to build a startup – but it has undoubtedly gotten easier. In part, that’s thanks to the formalization of best practices and dissemination of knowledge. In Silicon Valley’s early days, few knew how to create and run a high-growth business. Now, the world is dotted with entrepreneurs and operators that have been a part of both successes and failures, each with corresponding lessons.

Media extends this once recondite information to those that have yet to experience tech entrepreneurship for themselves. A teenager in Indonesia with an internet connection can read Paul Graham’s essay on “doing things that don’t scale” and immediately get some sense of what it takes to get a new project off the ground.

Obliquely, this has supported the success of solo investors. Once upon a time, venture capitalists were holders of such treasured information. Almost no one else had the privilege of seeing dozens of startup stories play out across eras with access to inside information. In an immature ecosystem, founders relied on this wisdom and had few places to find it.

The market has moved on since then, eroding an advantage of traditional firms. While institutional knowledge is still valuable, many best practices are now public. As a result, contemporary entrepreneurs may need the old guard less than they used to. In removing that traditional strength, solo investors are comparatively advantaged.

Shift 4: Tech and investing hit the mainstream

I had already graduated college by the time I first heard the term “venture capital.” A friend and I were talking about what we hoped to do now that we’d finished our schooling and off-handedly they expressed an interest in the field. It would take another couple of years for me to learn what this “venture” world actually entailed.

It seems unlikely that I could be quite so insulated from the industry were I an undergraduate today. Technology is the story of our era – it permeates everything from business to politics to art. As that has happened, the backers of this age’s biggest technological winners have risen in prominence. In the next few months alone, screens big and small will be visited by stories of Adam Neumann, Travis Kalanick, Benchmark, and SoftBank.

This increased awareness seems to have translated into greater interest in joining the sector. Venture capital draws applicants from startups, big tech, banking, consulting, and journalism, among other fields. Though traditional firms may not be able to digest as much capital as massive LPs would like, they are still extremely efficient from a headcount perspective. A handful of investors can manage hundreds of millions or more relatively simply. That means that even as the industry has grown, it can’t keep up with candidate demand.

Many of the solo investors I spoke with said that they started their own funds because they didn’t have a clear other option. Some did so because they felt no other firm was capitalizing on the opportunity they saw. Ariana Thacker of Conscience described her journey:

I am specifically passionate about partnering with early-stage founders innovating at the intersection of consumer and science. I saw becoming a solo-GP as a way to fully execute on my vision to pioneer and support founders operating at this intersection. There was no other firm like Conscience when I started, and hence I took the initiative to build and make it happen.

The increase of interest in venture capital investing has not been absorbed by existing players. At the same time, it has sparked new observations that traditional funds might have missed. Both have supported the rise of the solo GP.

Shift 5: Infrastructure has made going solo simpler

Beyond more general technological improvements, there have been sharp upgrades in the fund management space. Ten years ago, Carta had not been founded. AngelList was only two years old. Both are now core pieces of infrastructure for fund managers large and small, used to manage cap tables, track investments, raise money, and handle fund administration.

It once took weeks or longer to set up a new fund. That process is much simpler now, as is staying on top of changes to a portfolio. While solo investors existed before the advent of such infrastructure, it has no doubt made the model more efficient and allowed those with existing professional commitments to enter the fray.

Don't miss our next briefing. Our work is designed to help you understand the most important trends shaping the future, and to capitalize on change. Join 64,000 others today.

The players

With a definition set and the catalysts identified, it’s time to meet the players that compose this scene. I’ll do my best to differentiate between “solo capitalists” as per Basu Trivedi’s definition and those that may sit outside that characterization but feel spiritually aligned with it. We’ll also highlight the funds getting in on the action and talk through the path to going solo.

Solo capitalists

If we limit ourselves to those with funds over $50 million that lead rounds and have no other investors on the team, the pool of solo capitalists is rather small.

Oren Zeev is perhaps the most established example that fits this bill. After serving as a GP at Apax, a private equity firm, Zeev began investing independently, starting in 2007. Today, he reportedly manages more than $1 billion in assets under management (AUM) and frequently leads rounds, even at the later stage. Zeev led the $110 million Series D into the creative community, Domestika, announced last week.

Formerly the CEO of Color Genomics, Elad Gil seems to operate at a similar level. In August of 2021, he was rumored to be in the midst of raising a $620 million fund and recently led management platform Lattice’s Series F.

Shana Fisher, founder of Third Kind was an early mover in this space. Since beginning to invest in 2010, the former Microsoft executive has closed at least two funds. Her 2019 vintage is pegged at $65 million. Fisher also leads rounds, though they seem to be concentrated at the earlier stage, such as Third Kind’s backing of creator platform Bubblehouse.

Of course, as mentioned, Josh Buckley adheres to the original definition. He already manages hundreds of millions of dollars, and has led rounds into companies like gaming startup Playco and Pakistani freight marketplace, Bridgelinx.

Formerly of Stripe, Lachy Groom is another player in this space. In July of last year, Groom reportedly raised a $250 million Fund III and has led investments into companies like Stark Bank, Ethyca, and ContainIQ.

Array Ventures’ Shruti Gandhi raised a new $56 million fund in December and has led several rounds including a recent investment into product management tool, Chisel. Like Third Kind, Array is focused on early-stage investments and in that respect perhaps represents a slight deviation from the original definition.

After angel investing for several years, Zach Coelius announced a firm in mid-2020. His inaugural fund totaled $45 million and had a sole LP, Industry Ventures. At that scale, he is just a tick below Basu Trivedi's benchmark, but worth including. Per Crunchbase, Coelius Capital has led one round to date, a seed investment into insurance company Billy.

This is not intended to be an exhaustive list and as we’ve already discussed, the boundaries of this definition are hazy. Nevertheless, the seven individuals highlighted embody the term’s original definition.

Solo GPs

If there are comparatively few true “solo capitalists” there is a much larger pool of “solo GPs.” These investors differ from those mentioned in that they may operate smaller funds or are yet to lead rounds.

Players I’ve been alerted to in this space include Bri Kimmel of Work Life Ventures, Packy McCormick of Not Boring Capital, Monique Woodard of Cake Ventures, Vaibhav Domkundwar of Better Capital, Peter Boyce II of Stellation Capital, Harry Stebbings of 20VC Fund, Andreas Klinger of Remote First Capital, Soona Amhaz of Volt Capital, Nico Wittenborn of Adjacent, Alice Lloyd George of Rogue, Nik Milanović of The Fintech Fund, Turner Novak of Banana Capital and Ian Rountree of Cantos. Some, like Stebbings, manage large funds, with at least $140 million in AUM.

This group differs from super angels in that they seem to have raised institutional capital of some kind. Of course, these categories are fluid – a “solo GP” today may become a “solo capitalist” by tomorrow.

Super angels

Intermingling with this group are a cohort we might term “super angels.” Rather than allocate institutional money, these individuals invest their own, or perhaps manage some on behalf of friendly individuals. Some may have equivalently large assets under management and can have as profound an effect on a cap table.

Someone like Lenny Rachitsky seems to fit in this category, though his range of activities defies easy classification. In addition to serving as a scout for traditional funds, Rachitsky also helps manage AirAngels, and invests his own capital. He has done so extremely successfully with a recent AngelList piece highlighting him as one of the platform’s twenty top “external co-investors.” In our interaction, Rachitsky was kind enough to elaborate on this performance:

If you look at the money I’ve put in, and the current value of all of my angel activity (including carry on scouts and syndicate deals), I’m up 25x overall. It’s not a fair stat, because carry is free upside, but it does end up being very real, and it shows the leverage you can get as an angel investor.

The AngelList piece lists Rachitsky alongside Elad Gil, Josh Buckley, Harry Stebbings, Naval Ravikant, James Beshara, and Jack Altman. The final three of that list may also fit the “super angel description,” though it’s possible some of the money they invest comes from outside parties. Another frequently mentioned player is Gokul Rajaram, formerly of Facebook and DoorDash.

We might reasonably add the many investors that run “Rolling Funds” in the definition. Though these individuals do manage outside capital, the method of raising it feels more aligned with the bottom-up ethos of angel investors. Some of those highlighted by AngelList include Julian Shapiro, Shaan Puri, Sahil Lavingia of SHL Capital, Cindy Bi’s CapitalX, and many others.

Whatever definition given, each of the individuals mentioned in the three categories above act as solo investors, have made significant impacts on the ecosystem, and are changing how the game is played.

Limited partners

Few businesses are vulnerable to “key person risk” more than venture capital. The small size of firms means that the loss of even a single rainmaker can meaningfully dent a firm. Firms founded by solo investors amplify this vulnerability to its logical maximum.

Monique Woodard noted that this risk has surfaced in discussions with LPs:

I’ve spent time with some institutions who are still trying to wrap their heads around the solo capitalist movement and decide if they should invest in solo GP funds. Some of them see operational risk, some of them see “hit by a bus” risk, but I believe that we are in an era where solo capitalists have the resources to be just as operationally excellent as a firm that has two partners. And frankly, any one of us can get hit by a bus.

While this risk may be too much for some LPs, others take a different view of matters. One source that previously worked at an institutional LP argued it shouldn’t matter much:

[B]ecause VC investing is minority investing, if the GP dissolves, the underlying investments aren’t hurt much...[Compare that] to buyout investing, where if a GP dissolves, the manager of the underlying companies dissolves.

Another obvious difference between solo and team models is that the former, by definition, has an expiry date, a twist on “key person risk.” While teams can ride out the retirement of one partner and may be more resilient to generational change, solo funds end when the GP wants or needs to.

The same source highlighted that this might be a particular concern with solo investors. If GPs don’t succeed in raising large funds, management fees may not be enough to sustain them over the long term. If they do, the economics can become so favorable that they may choose to transform their practice into a family office or move onto leisure activities.

Again, while some LPs prefer to align themselves with funds that have the ability to compound over generations, others are excited by the chance to work with a new manager that has no goals to build an empire. As funds grow AUM, returns can often suffer, and every new investment management team must be underwritten. Planned obsolescence may actually be an enticement to some. In conversation, Basu Trivedi raised this point, saying “At some point you have to shut the lights down…I think some institutions view [an expiration date] as a feature, not a bug.”

Large endowments are getting into the mix. While Yale’s famed team has steered clear of solo investors, apparently expressing a preference for investment teams, Harvard has shown no such shyness. One source I spoke with suggested that Groom, Buckley, Boyce and others have all raised from the Cambridge school’s endowment. MITIMCo, affiliated with MIT, has an established “emerging managers” program and Notre Dame was also mentioned as being in the mix.

Fund of funds Horsley Bridge Partners is also rumoured to be a backer of solo investors, including Wittenborn at Adjacent. The firm has the benefit of experience in this regard, having funded an early generation of solo investors in Roger Ehrenberg of IA and Steve Anderson of Baseline. Other frequently mentioned LPs include Industry Ventures, Truebridge-Kauffman, and Cendana Capital. The latter narrowly focuses on managers investing at the early stages.

The solo pipeline

How do you become a solo investor? By definition, those in this field follow an unfurrowed path. Still, though every story is different, a few “solo investor” pipelines have emerged:

Build an audience.

Spin out from a fund.

Start a company.

Find an overlooked niche.

Leverage a mafia.

Build an audience

Several of the solo investors mentioned began as creators. Rachitsky, McCormick, and Milanović all write newsletters, Stebbings and Beshara run podcasts, and Turner Novak is one of VC’s meme kings. Lit, the pseudonymous founder of Litquidity, a media business, is another member of this group. They highlighted the power of an audience to hone thinking and see new deals:

Investors can build their own audiences, distribution, and get their ideas out to a niche group that allows them to see differentiated deal flow at a more personal level.

While attention and affinity can be well translated into deal access, capitalizing fully often requires outside firepower. Milanović described his journey to raising a fund after realizing he was leaving allocation on the table:

I had been [investing] informally by managing an angel syndicate. At the ~1 year mark, I took a look at what had been going well vs. poorly. What had been going well was that we had a great group of sophisticated fintech people in the syndicate and we were getting into super competitive deals. But we were not saturating the allocation we were offered, which was really the genesis for starting the fund…

Spin out from a fund

Though less common, some solo investors have previously worked at traditional funds. Before starting Stellation, Boyce was a partner at General Catalyst while Lloyd George worked at RRE. Gandhi worked at True Ventures and advised Bullpen Capital. She also currently serves as a commissioner for SFERS, the $25 billion pension plan for San Francisco’s workers. Those that arrive from this route benefit from having cultivated an investing style, developed a track record, and fostered a network of fellow investors, entrepreneurs, and limited partners.

Start a company

Current and former entrepreneurs bring operational expertise to the table that even tenured investors may not have. Naval Ravikant, Jack Altman, and Josh Buckley are all high profile examples here. While these investors must juggle multiple responsibilities, they have the benefit of having played the game at a high-level. Founders that ally with them bring aboard a mentor that may be able to provide much higher fidelity advice than those that have spent their careers in more traditional industries.

One former large fund manager and LP in solo GP funds suggested this might be the optimal profile:

I tend to think the best performing solo-GPs over the longer run will be operators, either founders or highly visible execs at the top 1% of companies (Stripe, Slack, Airbnb) where they know defecting, amazing talent, from the early build years of the company, or they just have the absolute best purview on a specific market.

As we’ll note shortly, owning a company mafia can also provide access to this network.

Specialize

Some solo investors succeed by carving out a niche that other funds are overlooking. For example, Ian Rountree of Cantos has built a reputation in early-stage deep tech while Soona Amhaz’s Volt Capital is crypto-focused. Amhaz highlighted this as part of her edge:

I’ve invested through multiple boom-bust cycles so have a longer term view of the space as opposed to the VCs that are just now getting into crypto. Additionally, I’m able to provide relevant insights that are unique to our industry.

Specialization does not have to be limited to new technologies. For example, Andreas Klinger started Remote First Capital to capitalize on the global trend:

I tried convincing VC friends to invest in companies I believed in and struggled. So I raised money from a few people who also believed in remote work and started investing on my own. After covid, the whole world saw its potential.

Woodard invests in different cultural trends, focused on “companies that touch areas of demographic change,” including aging populations, female consumers, and the “New Majority,” the trend of America becoming primarily composed of formerly “minority” groups. Woodard felt her focus on these areas didn’t line up with a traditional venture job, but could prove invaluable to founders:

After investing at a firm, I knew that I had a clear point of view and thesis that didn’t really lend itself to taking a role inside an existing venture firm. I’ve always been a builder and an entrepreneur, so I applied that entrepreneurial focus to starting a venture firm.

Founders often want to work with me because they know that I have a point of view and an understanding of demographic categories that other firms probably haven’t gone as deep on. Ultimately, I think it’s been my ability to show expertise in categories like aging that has resonated most strongly with founders.

Some solo investors experiment with structure. Fern Gouveia, a former founder in the middle of raising a solo fund, discussed how he hoped to tailor his firm to the crypto space:

I believe that the traditional org structure of a VC will not work in crypto given everything happening with DAOs, community raises, NFT mints…the best funds will be a mix of VC and hedge fund. I approached smaller players who are open to letting me play with this idea and are more open to having a flexible mandate.

Belong to a mafia

Several of the solo investors mentioned emerged after working at a generational business. Rachitsky spent seven years at Airbnb, Groom spent the same at Stripe and Rajaram worked at Google, Facebook, and Doordash. Each of these ecosystems is rich with talent that may start businesses of their own or can be well-directed to portfolio companies. Rachitsky mentioned that this is part of his pitch:

When I talk to founders, I also pitch them on the value of bringing in the Airbnb alumni network (as a hiring pool, a source of advice, and distribution), which resonates powerfully with a lot of founders.

While these different pipelines may go some way to explaining how solo investors emerge, we’ve yet to fully unpack how they win.

Winning solo

Above all, the triumph of solo investors is a feat of counterpositioning. While traditional venture firms are stereotyped as slow-moving and extractive, this solitary breed wins by speedrunning the process and operating as a trusted confidant.

Though each investor has their own strengths and weaknesses, there is something approaching a baseline playbook. Almost all the solo investors and other sources I spoke to highlighted one or more of the following dictums:

Move fast

Be responsive

Be empathetic

Offer mastery

Provide distribution

Move fast

Every venture capital firm needs a version of the Domino’s pizza tracker. Where is your deal? Are you at the “diligence” phase or is it decision time? Should you buckle up for another month or could you get an answer by the end of the week?

The variation and opacity of the traditional fundraising process is one of venture capital’s great self-inflicted injuries. Unfortunately, it is a tricky one to heal. The myriad moving pieces – deals, partners, portfolio companies, board meetings, investment committees – conspire to thwart a reliably timely process.

Solo investors keep it simple. Thanks to their unilateral position, they’re able to make investment decisions rapidly, winning allocation by being decisive. Shruti Gandhi of Array Ventures noted that “We usually decide on the call and spend more time with additional diligence, negotiating terms, etc.”

Soona Amhaz from Volt also mentioned her rapid turnaround: “My investment process typically takes a few days. I can move fast since there’s less red tape to get through to finalize the decision.”

This cycle seems to be common among solo investors and represents a considerable shift from traditional dynamics.

Be responsive

Such speed persists once an investment has been made. Several solo investors I spoke with remarked that part of their value was responsiveness. Nik Milanović, for example, said “You can ask any founder I invested in, I respond almost immediately.”

Lenny Rachitsky elaborated on this theme:

I tell [founders] they can ping me anytime, and many do. I often give them my number, and always respond immediately whenever a founder reaches out. Some founders SMS me once a week, some never want to chat again. It really depends on what they need, and what their biggest bottlenecks are at the time. At this scale, I rarely proactively reach out and ask if I can help, but I respond to every investor update and pitch in on every ask that I can help with.

While some traditional investors certainly shine in this respect, solo investors seem to stand out. That may be because many are entrepreneurs themselves, and as such, operate on more similar timelines.

Be empathetic

Solo investors are founders. In some cases that’s true several times over–many of those mentioned run startups in addition to investing. But even without this being the case, the act of formalizing a solitary investment practice is entrepreneurial. It is not easy to start a firm; those that do so are often more aligned with founders than traditional VCs. As Ian Rountree of Cantos put it, “Solo GPs are founders themselves.” Ariana Thacker of Conscience also described this alignment:

Birthing Conscience has allowed me to emotionally and intellectually relate to founders with far more depth, empathy, and understanding. I feel we are kindred spirits and underdogs, working alongside each other to do the “impossible” aligned with our respective missions…I know I’m not alone in this journey, most of my solo capitalist peers are working 60-80+ hour weeks, and we are jumping through the same high-flying hoops to just make it.

Sharing the experience of the builders it finances gives solo capitalists empathy that lifelong investors may lack. It can translate into big things and little ones. For example, Thacker noted that she gives every founder she invests in access to a Calendly link so that they can book time with her without needing coordination. It might seem like a small kindness, but it’s an indication of a certain understanding.

As one solo investor described their sell to me: “I am your friend first…No distractions, it’s me and you. Let’s go.”

Offer mastery

Some solo investors appeal simply through their excellence or mastery over a certain domain that holds tangible value. As Julian Shapiro noted, “Being solo is not significant. What’s interesting is being an operator investor.” Those that fit that bill carry with them the empathy noted earlier as well as valuable expertise.

For example, someone like Lachy Groom has contributed to the creation of an exceptionally high-performance financial business in Stripe. Such experience is rare and likely to be valuable to a range of startups. Lenny Rachitsky is an eminent product and growth craftsperson – both are essential components of any business.

A more unusual example of this comes in the form of someone like Galileo Russell. The investment YouTuber who goes by “Gali” runs an active syndicate practice called HyperGuap that has invested in startups like Rainbow. He is well-known for championing a bull-thesis in Tesla. His expertise in the space contributed to Gali landing a seat on the board of Arcimoto, another publicly-traded electric vehicle company. As new players crop up in that ecosystem, Gali is likely to be an attractive capital partner to many.

Ultimately, Andreas Klinger summarized this element of the solo investor appeal succinctly:

Founders need a support system around them at the early stages – that’s very specific to each founder and company. Most angels and micro-funds are known for a certain expertise, skill, support, brand or network.

The most successful solo investors bring a form of mastery to the table whether that’s through a well-honed craft or a wealth of relevant experience.

Provide distribution

Social media advertising has reached a saturation point, making it increasingly difficult to stand out. Such congestion has made reliable distribution more valuable than ever. Few traditional venture firms offer meaningful support in this area. Certainly, many can connect their portfolio CEOs to PR firms or help them hire in-house marketers and creators. But in terms of telling a company’s story directly, founders usually must look beyond their capital partners.

Creator investors are stepping into the breach. With large, relevant audiences already established, these capitalists can accelerate a company’s visibility and acquisition. In that respect, they act as a marketing alternative.

For example, Gali noted that part of his sell to companies is to explicitly demonstrate his contribution on this front. “I’m like let’s do a podcast or let me tweet about you,” he said. “You’ll see my value.” Often, traditional investors over-promise and under-deliver; creators can tangibly make a difference and demonstrate their reach from day one.

Such distribution is likely to work best if allied with exceptional storytelling abilities. While raising attention on social media is beneficial, creating narratives for businesses through podcasts and written work may be more enduringly valuable. One of the best at this is Packy McCormick via Not Boring. Will Manidis, founder of ScienceIO, highlighted the impact a Not Boring piece had on his business:

This is extraordinary, almost insane. Any traditional fund that hit half of these numbers would be doing remarkable work – that it came from one person writing one piece shows the power of a compelling narrative, shared with the right audience. While working with a solo investor might not guarantee coverage, it’s likely to help. Someone of McCormick’s calibre undoubtedly has much more inbound interest than he can fill; the easiest filter is companies you know well and explicitly believe in.

To reframe one of the points made above, a McCormick story effectively cut ScienceIO’s CAC by roughly half. While its impact might tail off over time, it is still likely to be a source of some inbound and a valuable conversion tool. This is the sneaky power of this approach – by aligning with leading creators, companies can radically reduce their CAC, and improve recruiting – perhaps permanently.

One former investor at a large LP, who wished to remain anonymous, highlighted this power:

Any brand association with a Packy/Mario or the like just reconfirms to the market that this company is a standout. In the early days being known in a category helps you compound your mini-brand faster. Then you have a cheaper cost to acquire not only customers, but talent, partners and further awareness.

(Aside: it would be remiss not to mention that of course I would believe this. Not only is it extremely beneficial for me, it’s also one of the primary themes of this newsletter. By championing this argument, however sincere, I indirectly elevate the importance of my work. You should feel free to challenge that bias 😉.)

Challenges

It’s not easy to operate a fund alone. From the outside it might look like writing checks and sending tweets, but under the hood there are complicated operations, real struggles, and clear tradeoffs. As Thacker remarked:

Being a solo GP is an incredibly intense and unique job from a time commitment, pace of execution, and breadth / depth of skill set required. It’s not just about knowing how to invest and source, but you also must handle all of the operations, fundraising, brand building, and scaling that comes with running a successful firm for the long-term.

Solo investors face challenges at every stage of the investing process, and several outside it.

Sourcing

As the size of the startup ecosystem has grown, the number of viable companies has proliferated with it. This has made sourcing an increasingly important part of the VC job. While this might be most pronounced for sub-Tier 1 firms that have fewer good companies knocking on their door, it impacts everyone. Teams of analysts and associates are tasked with hunting down the next big thing and getting there first.

Solo investors may struggle on this front. It’s close to impossible to achieve equivalent coverage as an individual, particularly if balancing other major commitments.

While some solo investors I spoke with mentioned that they see deals before another investor has committed, many rely on referrals from other firms. As long as a solo investor doesn’t take too large an allocation, it is accretive for incumbent funds to loop in individuals that have something concrete to add and that may infer a certain cache. This relationship becomes more complicated as solo investors raise larger funds – as one anonymous source put it, by growing AUM these individuals may “crowd out their access point.” To thrive with larger check sizes, solo investors need to have sourcing channels distinct from competitive funds.

For investors like Groom, that may come from his Stripe network. Someone like Buckley can leverage the power of Product Hunt’s reach and his visibility into Hyper’s burgeoning portfolio. Creators and community builders may be able to leverage their audiences. Lit noted that they have “an audience of 1M+ individuals and have established a network that allows [them] access to deal flow.” Milanović mentioned that more than 90% of his deals come through “warm referrals,” which included community members and readers. Amhaz pointed to events like P2P Miami, a crypto get together, as a valuable sourcing channel.

Interestingly, Rachitsky was frank in stating that his audience and community had proved more useful for gaining access than discovering deals:

One of my biggest surprises with the newsletter’s success is that it more helps me get into deals, vs. creating a ton of deal flow from readers.

While most solo investors can happily stay at a size small enough to collaborate with big firms, reducing the importance of broad sourcing, a few must rely on other strategies.

Diligence

Solo investors often don’t have the bandwidth to thoroughly diligence the companies they evaluate. As part of their core appeal is speed, even if they have no other engagements, deep understanding usually takes longer than a few days. It’s worth noting that this isn’t always the case, with some investors taking a more deliberate approach, though it’s less common.

To gain conviction, solo investors rely on others in their network. For example, Neil Murray, who runs The Nordic Web Ventures alongside his full-time role as CEO of Playmaker mentioned that he often outsources diligence to his limited partners or others with relevant expertise. Several others noted that once a lead is in place, they conduct relatively little diligence.

The interesting thing about this trend is that it effectively segments venture capital: one party may be responsible for winning a deal but divorced from the analysis process. While this happens in traditional firms, the version suggested here is much more pronounced and may presage further shifts. Perhaps in the future, firms will distinguish between “front-end” dealmakers tasked with wooing entrepreneurs and “back-end” analysts, forming the investment rationale.

From one vantage, this is an entirely rational approach. Solo investors almost certainly can’t approximate the same depth of diligence as a large fund (at least not with equivalent breadth) so why not trust their judgement? Just as “nobody ever got fired for buying IBM,” few solo investors are going to attract ire for following Sequoia into a round.

However, if investors apply this logic too liberally, they may end up with a haphazard portfolio. The former manager of a large fund who has backed solo investors commented, saying “I would not be comfortable with a [solo manager] “YOLO’ing” into a round with over $1M without extensive work, but I see this happening all the time.” The lone wolf investor must surf social signals and try to make educated decisions on limited information.

Support

“It’s basically impossible to be a lead investor in 100 companies,” Basu Trivedi noted. In part, that’s because venture firms have taken on new responsibilities over the past decade. Rather than simply providing advice – time-intensive in and of itself – many funds now run dedicated recruiting, marketing, and operational practices.

Solo investors typically don’t have bandwidth to offer comparable services. Murray noted that there are many initiatives he might want to undertake on behalf of his founders but can’t quite fit in:

Even if it is your full-time job then this is still an issue, as you want to focus on the things that truly move the needle, finding new investments and helping existing, however there are plenty of other things operationally that you know would add value (arranging in-person events, maintaining an engaging Slack channel with all your founders and LPs, talks from good people for your founders) that you can struggle to find time for as one person doing it all.

Perhaps the salient question is: do entrepreneurs want these added services? Do they expect them?

Some certainly do. Andreeseen Horowitz may be the most advanced firm in terms of portfolio support, offering a range of services. For founders like Sam Corcos of Levels, that’s been a massive boon. In October of last year, he tweeted out how valuable the firm had been:

How can a solo investor compete with the work and expertise of 94 people, not to mention the many that enable those Corcos interacted with?

For someone like Corcos, replacing a16z with a solo investor almost certainly wouldn’t have been the right move. He has clearly found a way to leverage the model to its full potential. However, Corcos is also an unusual case. As I discussed in our piece on Levels, he is a genuinely singular executive with superpowers around productivity and networking. It is not altogether surprising that a man who maintains a spreadsheet of 1,000 people to stay in touch with might maximize this value.

Other founders may prefer a more personal relationship with a single point of contact. While a solo investor may not be able to do everything, they can fulfill this need better than a firm. In some cases, they may have expertise or access that literally does not exist anywhere else, making them the rarest of commodities.

Finally, it’s worth returning to the McCormick example mentioned earlier. Solo investors do not need to solve every problem, especially if they are not leading rounds. It’s a startup trope that entrepreneurs should be “T-Shaped,” capable of applying their skills across scenarios, but deeply knowledgeable about a specific sector. The solo trend favors “T-Shaped” investors – those intelligent enough to analyze different businesses but gifted enough to add outsize value in one domain.

Administrative work

Though the state of the art has improved significantly, solo investors face many administrative challenges. To succeed, many hire additional support. Several of the large name solo capitalists mentioned apparently leverage Chief of Staffs to handle operational matters, while others have begun building a back office team. Soona Amhaz remarked on this, stating:

[The solo capitalist term] is a misnomer in that many solo capitalists are not running a one-person operation. The investor may be the name or brand or only GP but [they] usually have a team to support with ops, finance, portco support, admin, backoffice, and sourcing/diligence. For instance, at Volt Capital we’ve brought on a CFO, analysts, and venture partners.

While some investors add headcount, others keep their eyes open for new tooling. Fern Gouveia noted that creating a hybrid venture/hedge fund has opened his eyes to missing infrastructure:

With this structure of hedge fund and VC, I am using multiple tools to track allocations and positions. [It would] be great to have a tool where I can view positions in liquid tokens and startups that are then linked to the back office requirements I need for audits, LP updates, accounting, [and so on].

As investing continues to move into mainstream consciousness, bringing new managers with it, we should expect to see products emerge to serve increasingly sophisticated use cases.

Sizing up

Most of the solo investors we’ve mentioned run funds in the tens, rather than hundreds, of millions. In many cases, that means they may be unable to take full advantage of pro-rata rights. This clause gives investors the chance to invest in future rounds to maintain their stake in a business. If you choose not to exercise your pro rata, subsequent financing rounds dilute the size of your position.

For many, failing to appropriately size up a position can be the difference between incredible mark ups and real money distributed. There doesn’t seem to be a perfect solution here.

A common solution is to spin up special purpose vehicles (SPVs) to fill pro-rata allocation. Rather than that money coming from the solo investor’s fund, it comes from LPs, other founders, and members of a community. Amhaz spoke about this:

Typically, I can get more allocation in follow-on rounds than I have allotted for reserves – in that instance, I spin up SPVs to maximize exposure. Volt Capital LPs will typically get first preference and fill out the SPVs.

Julian Shapiro noted that he follows a similar playbook and prefers working with LPs that want to invest in his fund’s breakout stars. “I want there to be this mutual fit where they get value from me, so that I'm not a commodity to them,” he said.

Not all find SPVs effective. Andreas Klinger remarked that they “tend to be too slow.” It can be difficult to round up interest, particularly if a company isn’t sufficiently well-known. “Once it’s hot,” he added, “it’s basically too late.”

To simplify matters, some solo investors simply pass on pro-rata to large LPs, removing the stress of running an open syndicate. Many of these LPs may be GPs in larger funds. While some of the relationships involve shared economics, in other instances, it may act as a kind of payback for backing the solo manager’s vehicle. The anonymous former institutional LP noted:

Many are giving away to larger GPs and LPs that co-invest. Even if they want to invest in pro rata, it takes time that they don’t have to [due diligence].

The former manager of a large fund made a similar claim:

Many [solo GPs] I've backed have taken large LP checks from a16z/Thrive/TPG and others. Those funds tend to get exclusive rights to pro-rata and follow on rounds...again this will knee cap returns. It is certainly appealing to get that money in the door but it limits future growth and ability to show institutional LPs a track record worthy of a bigger fund II.

Solo investors have the choice of either increasing their AUM, adding to their work by running SPVs, or giving away later rounds. Each has its drawbacks.

Identity

A more esoteric challenge is the matter of identity. As mentioned by Jackson Dahl in our “What to Watch in Crypto in 2022” piece, pseudonymous influencers have risen in prominence over recent years. This seems to be particularly true in the crypto world where people like Gmoney, 0xMaki, and various CryptoPunk avatars have amassed large, influential audiences. At some point, many of these builders may want to more actively invest, if they are not doing so already.

How do they handle the matter of identity? After all, investing relationships are typically personal. I asked Lit from Litquidity how they handled sharing their identity, responding that they only do so under NDA. They added, “The relationship is built on trust. People who want me on the cap table know what the Litquidity brand is and know that there is a trustworthy person behind it.”

While Lit seems to have found a solution, it’s unclear whether that will work for all companies. New tooling may need to emerge to better handle this class of solo investor.

Move and countermove

Should traditional venture firms worry about solo investors? For leading firms, this movement has likely not caused significant disruption. When I asked Basu Trivedi for his thoughts on solo capitalists’ success rate, he responded, “Do I think they have a majority win rate against the big firms? I don’t think so.” He stressed that competitiveness almost certainly varies significantly among practitioners.

While leading firms are probably more worried about Tiger Global than solo capitalists, they may want to act proactively. Moreover, any fund beneath the top few tiers has almost certainly felt the impact of these rogue agents. Given the tangible value that so many provide, along with the improved service, it can be something of a no-brainer for an entrepreneur to ease out a second-rate fund in favor of a first class individual. It’s time for venture firms to react and counterpunch.

Make solos seem more like firms

The “solo capitalist” moniker has created a cache that isn’t altogether logical. It’s true that there are structural advantages to maintaining a small team. As we’ve mentioned, that enables fast decision making and closer relationships.

But is a firm with one GP really so different from one with two? What about three? Is a solo investor really that much faster? That much more personal?

Solo investors automatically get the perceived benefits of being solo without the baggage. They are compared to VCs on favorable dimensions but almost never on unfavorable ones. As Gouveia noted, “VCs don't always get a good rep so being viewed as an individual instead of a firm also humanizes us in the eyes of the founder.”

If I were a scheming old school venture capitalist, I would want to disrupt this narrative. This is much easier said than done, of course. It is a bad look for Goliath to pick on David, even if David is now of a similar size. The underdog status of solo investors may protect them from meaningful criticism, at least for a time. At some point, though, the model will be questioned more seriously. As Ian Rountree said:

There’s always a pendulum swinging somewhere. Founders in a few years may say they’re not getting enough support from solo-capitalists spread too thin and some of us may join forces…

Make firms more like solos

Undercutting solo investors is a dangerous game – borrowing from them is much savvier. Rather than trying to encourage solo-led firms to be judged like other funds, traditional vehicles need to embrace the service, personality, and empathy of this new wave. Perhaps the most obvious way to do so is by elevating the brands of individual partners. Julian Shapiro suggested that venture partners should “be on YouTube” or “writing longform blog posts.”

Failing that, firms could also attempt to woo solo investors to join them. Some will wish to retain their independence but adding robust back office support and more stability could prove attractive to many. This might be a particularly sharp move for creator investors in so much as they address the weak distribution of many existing firms.

While this would build some distribution power, firms should also invest in creating firm-level media properties. A16z is the clear leader in this regard, boasting a collection of podcasts. It’s too early to judge the success of Future, it’s online publication, but the attempt demonstrates an understanding of the changes to the ecosystem.

Redpoint seems to be taking a similar tack, hiring a team of creators and budgeting $1 million to a property named “Start.” The new in-house media brand is expected to include videos, written pieces, and TikTok clips.

The fact that so few other funds have followed in a16z and Redpoint’s footsteps suggests that incumbents are either asleep to these new dynamics or feel unable to develop a new competency. Those that want to remain relevant should wake up and begin to expand their skill set.

Formalize LP investments

Incumbent GPs often write the first checks to funds managed by solo investors. Not only is this a way to promote the industry’s next wave, it offers visibility into new deals. Incumbent funds should formalize this practice. They could set aside a fixed amount each year to invest in emerging managers or give funding to GPs, allocated at their discretion. Some could build educational resources for emerging managers, or create a platform that makes it easy for this group to leverage a firm’s infrastructure.

For example, what if every year Index picked five new managers to seed with $10 million. These solo investors would be free to raise additional funds but would, at least, have enough to go full-time. As part of the program, Index could provide mentorship, access to SOPs, and use of fund resources. In exchange, solo investors opened up their pipeline and brought Index in on breakout investments, sharing the economics. Index, or any sponsoring firm, could set a timeline for this arrangement: two years would be long enough to develop real rapport and reap the benefits.

This kind of arrangement seems like a clear win-win. Large venture funds could put slightly more money to work in a small fund of funds strategy, would get the halo effect of sponsoring new managers, build deep relationships with the next generation, and gain visibility into different businesses. Solo investors would have their work significantly de-risked, benefit from an established brand, learn from tenured investors, and capture some of the upside of their best investments.

Every Sunday, we unpack the trends, businesses, and leaders shaping the future. Join us today.

Future

Will the solo investor trend last? Will we see relatively more AUM managed by this group, or less? While many of the members of this cadre were optimistic about the future (unsurprisingly), those outside it seem to think it has legs, too. The former fund manager mentioned earlier said:

I strongly believe the [solo GP] model will be a big wave of change in VC, be it at scale $75M+ funds, or on the subscale side.

Let’s think through how contemporary solo investors might develop their practice in time.

Scaling out

Operating alone doesn’t have to be a permanent state of affairs. For many, it was more of a quirk of circumstance rather than an indication of a clear preference. Monique Woodard said:

Starting a firm with someone is a lot like getting married and there was a finite number of people that I would have done that with. Rather than have a shotgun wedding, I felt confident enough to just start building Cake as a solo GP.

At some point, those content to operate stag may find their forever business partner. We’ve seen that happen many times over the years. Jeff Morris, Jr. was a prominent solo GP but has since added investors to the fund he founded, Chapter One. Xuezhao Lan of Basis Set is another example. Lan outlined Basis Set’s maturation:

I started solo (we were the largest early stage fund raised by a solo woman at the time in 2017) and now manage $300M+ across 2 funds and have a team of investors and engineers like a tech company (more engineers than investors). Most LPs are nonprofit endowments & foundations.

Others may follow Lan’s lead, “scaling out” of their solo investment status and building funds with multiple partners at the helm.

Forming collectives

One alternative to adding headcount could be in creating collectives. The venture capital world is already governed by different alliances built on information and deal sharing. Solo GPs could band together to approximate the portfolio support offered by larger funds. One solo investor expressed interest in this approach:

Maybe there could be a network alliance for solo capitalists to enable each other’s “platforms”. My BD, Packy/Mario’s writing/research, Ryan [Hoover]’s product chops, Shrug’s influencer relationships, so on and so forth.

While alliances may form among existing players, structures built expressly for this purpose could thrive. An example is GTMfund, a network of go-to-market specialists that invest together. Collectives like this offer legible value and access to other operators. Depending on their decision-making structure, these groups may be able to make decisions quickly, though it’s hard to imagine they could be as fast as solo capitalists.

Ultimately, investors may find new, mutually-beneficial ways to collaborate and increase their bandwidth.

Improving equity

Women and minority groups remain extremely underrepresented in venture capital. The industry’s problems seem to exist in the solo investing cohort, too. As part of the solo capitalist movement’s maturation, these marginalized groups will hopefully receive further backing. Shruti Gandhi noted that there was “no diversity” among solo GPs and that “fewer trust solo women.”

Woodard elaborated on that topic, noting that the backing of diverse solo GPs can lead to the empowerment of often overlooked founders, sectors, and geographies:

There still isn’t enough capital going to women entrepreneurs, Black and Latino founders, founders working on really hard tech, entrepreneurs building outside of the coasts, emerging market entrepreneurs, and so on. I don’t think that solo capitalists alone solve for this, but I do believe that more capital managed by a wider variety of investors starts to move us in the right direction.

By now, the tech and venture ecosystems should be aware of these dynamics and must work to correct them. As this movement grows, it must become more representative, ensuring that innovation is not built only to accommodate existing paradigms.

As the old Jim Barker chestnut goes, there are only two ways to make money: bundling and unbundling. Which is to say that where venture capital began, perhaps it is returning. An industry founded by solo virtuosos like Arthur Rock developed into a team sport as it matured. Firms grew and established themselves, thriving thanks to their unique expertise, better information, and rich set of offerings. The new cadre of solo investors challenges this norm. Rather than indexing on research and portfolio services, these rogues win through speed, empathy, and by treating the venture asset class like any other – capable of being refined and disrupted. It represents a great unbundling, one that seems to have only just begun.

The Generalist’s work is provided for informational purposes only and should not be construed as legal, business, investment, or tax advice. You should always do your own research and consult advisors on these subjects. Our work may feature entities in which Generalist Capital, LLC or the author has invested.