If you missed last week's message, you can check out the story of how Zach and I met, here. Without further delay, I'll turn it over to Zach, founder, and CEO of Ro, and one of the most remarkable people I've ever met.

Brief

Rabbis in Cuba

The six businesses that prefaced Ro

Meeting Bloomberg, fixing showers, and cooking burritos

The problem with “hustle porn”

Embracing Kobe’s #mambamentality

The magic of Joan Didion

The moment Zach realized Ro had product/market fit

Origins

When he realized he wanted to be an entrepreneur

It sounds cheesy, but it really arose from a love of solving problems. My parents were always of the mindset that the best way to complain is to build something better or fix it yourself.

I started out by solving my own problems, ones that I experienced personally. That just felt like so much fun, you know? To solve the problems I felt in my own life and have this positive feedback loop where you actually see it work. It’s kind of intoxicating in that way.

On heroes

My entrepreneurial hero is my dad.

When I think about what we’re building at Ro, a lot of it is that we’re trying to recreate my dad with software. Our mission is to be a patient's first call. And my dad was always the first call for both me, my family, and my friends. Our home was a pharmacy, and if you had a question — whether that was about diabetes, heart disease, or an STD — the closet in our house could help. He’s saved each person in my family's life at some point.

The times when he couldn’t, when you might be served better by another doctor, he’d help you find that person and follow up. So he could either handle something himself, guiding you from beginning to end, or help you find the best person possible. Ultimately, that’s what we’re trying to do here at Ro.

Learning to break the rules

In terms of my development as an entrepreneur, there are two things my dad did that were amazing and really helped me build businesses.

The first lesson is this: strong opinions, loosely held. That’s not something he enforced explicitly but through practice. He was a big proponent of debate as a way to learn. As a highly-opinionated nine-year-old, I would argue whatever side I believed in ferociously, but then, just as I felt I had lost the argument, he’d have me switch sides. He’d show me how I could have argued my point another way, or thought of something differently. Over time, I learned to empathize with other points of view and beat up the opinions that I held. You can’t be so confident in your opinions that you don’t think there could be another option, another solution.

The second lesson was to understand when it’s ok to break the rules. Some parents are ok with their kids breaking the rules; others help their kids break the rules. There had to be a good reason, of course — but when he agreed that the rules were unfair or unjust he’d help me find ways around them.

Rabbis in Cuba

One example of that happened when I was getting ready to leave high school. I’d already gotten into Columbia and had another 6 months to go before graduating. I’d read this article in the New York Times saying there was no permanent rabbi in Cuba, and I’d become fascinated by it. My Dad knew that and said, “If you want to go to Cuba for a few months, I’ll help you make it happen.” And he did. I put a proposal together for my school, but it wouldn’t have happened without him convincing my headmaster. So as a 17-year-old, I spent three months living in Cuba on a religious and humanitarian license. It’s hard to describe how much I learned during that time, certainly more than I might have back at school.

When I think back on those lessons from the vantage of an entrepreneur, I realize how important they were to me. The first taught me to constantly keep learning, to look for new perspectives and opinions, never being fixed on your own. And the second lesson...look, the phrase “this is how it’s always been done” is kryptonite to a startup. He’s the one who helped me look at life and realize that just because something’s been done a certain way in the past, doesn’t mean it has to stay that way in the future.

In the arena

The first business: a medical device

The first company I started was in high school. We made tips for canes, initially as a solution to a problem my parents faced. Both of them had had strokes and needed canes to get around, but they kept experiencing pain in their wrist, elbows, and shoulder. The problem was the bottom of the cane.

So I worked with engineers to make something that I thought could help them and other people with the same issue. It was a tip that you could add to any cane, even one you bought at CVS, and it would help absorb the shock, reduce vibration, and increase the surface area to better suit your gait. It really worked for my parents, and we actually had a patent-pending at the time.

I learned a lot from that first experience. I wasn’t an engineer, but I found that I had a lot of motivation to read and obsess over problems like this and carry it through to an actual solution. It also taught me that I didn’t have to be an expert to solve a particular problem.

The second business: a marketplace for parking spaces

I took Brendan O’Flaherty’s urban economics class in college, it must have been in 2010 or 2011. This was a time when Zipcar and Uber were becoming really popular, though Zipcar was a much bigger deal at that point. It’s funny to think back now, but people really thought the future of transportation would be car sharing.

One of the big problems in New York City is parking — and so with my close friend Mason Silber, an engineer, we built an app to buy and sell parking spots. For $5, $10, $15, $20 you could post the parking spot you were in and sell it to someone who needed it. It also had a really strong single-player mode: we told users when they needed to move their car because of street cleanings, or gave them a warning when they were about to park in an illegal spot.

We actually won New York City’s Big Apps Award and got to meet Bloomberg, who was mayor at the time. But then I went to Booz to do consulting that summer and my co-founder went to Twitter.

The third business: a super-app for college students

The next year, my friends and I built something called Swap College. It was that classic college student startup where you try to jam six apps into one. We had online whiteboarding features, a messaging board, forums — just a whole mess of stuff.

What we missed was that one of the features was much more popular than the others: file sharing. We really should have doubled down on it. Students were uploading these incredible study guides and example papers that would get downloaded thousands of times, but we didn’t really know that was happening. It was only after I graduated that I saw the server costs and realized that I was paying hundreds of dollars a year for it.

In the end, it was an important lesson: listen to customers, and nail one thing.

The fourth business: the YC company

At the age of 22, I got into Y-Combinator. Shout was a real-time classifieds app focused on community. You could buy and sell tickets, reservations, or other services. It was also a safe place for users to be creative — we had actors offering to do things like delivering a rose while reciting Shakespeare. You could spin up your own marketplaces, too. So for example, users could create a “stream” for a specific group — like your college — and have a Shout instance run in that context.

We raised money from Accel, Index, Box, Slow, and a few other people. We ran the business for about two years but I had to shut it down when my sister got sick. We returned about 80% of capital back to investors, and I spent the next 6 months looking after her.

Coming to terms with the failure of Shout was hard. I had so closely linked the business to my self-worth that it was hard to extricate the two. Going through YC and raising millions of dollars at that age, I really felt like I was on top of the world — that this was how life was supposed to work. Then when things don’t work out, it rattles you, or it rattled me, at least. I was lucky that I had a partner, Cleo, that didn’t love me for the business I was building, but loved me for me. She slept in an apartment with no windows and rats, when I was making no money, and was always there for me, making me feel loved. I think it would have been much, much harder to handle that failure without her.

The fifth business: the pop-up burrito restaurant

Then, we ran a burrito restaurant. Boom Burritos was important to me because it got me back on the bike, and was just pure fun. It was also ridiculous. We were handing burritos and mason jars full of guacamole through the window of my apartment to Uber Eats couriers, cooking from a string of grills in the middle of the living room.

It was great to get back into the swing of things, but I knew it wasn’t what I wanted to do for the rest of my life. I was talking to friends about this recently — an interesting lens to apply to a new startup idea is “would I still be happy to have done it if it failed?”

That was one of the lessons of Boom. Food is such an amazing space to be in — it’s an art, feeding people. So of course the idea of succeeding in the space sounds amazing. I’d be thrilled to run a successful burrito restaurant like Chipotle. But would I be happy to run one that failed?

With both Shout and Boom, I realized these were ideas I really wanted to be successful, but I didn’t want to fail with them. With Ro, it was clear from the start: whatever happens, I want to have tried at this. Of course if we fail I would be devastated, but whatever the outcome, I know that the effort would be worth it to me.

The sixth business: the Airbnb of the future

I wasn’t making much money, so I started Airbnb’ing out my apartment part-time to cover my rent. I was lucky because my best friend Greg Rosen let me crash on his couch. He really was an amazing friend during that time — he basically fed and housed me.

One of the first guests I had in my apartment noticed that I had an Amazon Alexa and was really excited about that. At the time, they were still pretty new.

That gave Greg and me an idea: even if I couldn’t change the basics of the apartment — things like the location and square footage — maybe people would pay more if they got to interact with modern products, modern amenities. So we emailed like 20 startups and within a matter of days we’d gotten $25K worth of free stuff to showcase. We got a new bed, a couch, screens, a Boosted Board, Harry’s razors, a fridge full of Soylent; you name it, we had it.

We spent weeks integrating the different devices and building a personalized system for guests. Before you arrived you’d get a form from “Future BNB.” Then when you walked through the door, your favorite music would be playing, your favorite TV show would be cued up, restaurant recommendations based on your culinary preferences would show up on the dashboard along with the status of nearby subway stations. In the morning, you’d get an analysis of how you slept based on sensors on the bed.

It actually really worked. People were paying $350 a night for a pretty shitty apartment and having a great time. But there was a clear moment when I realized it wasn’t the business I wanted to build: I got a text from a guest one night at midnight saying that the shower had stopped working. I got out of bed, walked twenty blocks to fix it, and realized — I don’t want to be a landlord.

It couldn’t have felt differently when I had a similar task in the early days of Ro.

I was working as our customer support back then, and I remember someone’s package had gotten lost in the mail. When I emailed the patient back, they mentioned that they were in NYC, so I ran them their package. And I had a smile on my face while I was doing it.

On paper, those tasks are pretty similar: one you’re fixing a shower, the other you’re delivering a package. But the first I did grudgingly, and the second I couldn’t have been happier to do. That was one of the moments it became clear to me I’d found something I wanted to devote myself fully to.

Lessons

On finding inspiration

Mostly I’ve drawn on personal experience, with a few exceptions. The medical device I built, College Swap, Future BNB, and Ro all came out of struggles I faced or those around me did.

Parking Ally and Boom Burritos were a little different. They arose out of trends I’d observed. With Parking Ally it was clear that mobility was changing in cities and that tech had a role to play in that. With Boom, it was clear that the shift to cloud kitchens was a trend with legs.

Shout was a mix of both. In many ways it was building on the trends we’d observed with Parking Ally, albeit at a higher-level of abstraction. Fundamentally, both companies were localized mobile marketplaces. I’d also had a bunch of experience trying to buy and sell things on Craigslist in college, so I knew there was an opportunity to improve on that experience.

On idea “dating”

A lot of the time, I think people are afraid to fall out of love with a startup idea. Especially as first-time founders. They leave their job, and within a matter of days, they want to be up and running with a new idea, hanging on to it months after they’ve lost passion for it.

I think that comes from a fear of being seen as a failure. It’s something I felt when Shout failed but once I managed to separate myself from it, I was a lot freer to experiment with different ideas. It almost became a bit of a joke in my circle of friends. One week I’d be asking them to taste-test a burrito, the next I’d be asking for advice on sleep sensors. It was like, “what’s Zach working on now?”

In many ways, working on an idea is like dating. You might have a great first date with someone, or even a good few months together. But eventually, if you realize that’s not the person you want to spend the rest of your life with, you break up. And no one thinks any less of you for that, just that you and that other person weren’t the right fit.

It’s the same with any business idea. Maybe you love it to begin with, maybe a week later you’re still excited about it. But maybe six weeks in you learn something that makes you feel differently — the margin profile is worse than you’d imagined, or the demand is weaker. You should be able at that point to stop working on it and move on to something new. That doesn’t make you a failure, it just means you’re testing things out.

On obsession

One of my biggest strengths and weaknesses is that I’m obsessive. It’s something I’ve been working with an executive coach on to make sure that trait is more helpful than harmful.

With Ro, I found something that I feel so fulfilled obsessing about. I get so excited going down the healthcare rabbit hole, reading some thesis or economic report from 1975 about physician supply, trying to understand the space better to serve the products we build.

When we first started out, for example, we spent $300K of our $400K pre-seed round on building a pharmacy. A lot of people thought we were crazy to try and do that given the level of complexity — we bet the company we could.

To make it happen, I spent the weekend reading the New York State pharmacy law cover to cover, then read the federal pharmacy guidance. That research informed a fundamental piece of company infrastructure that’s continued to be critical: having our own pharmacies across the country has fuelled our growth and facilitated a better patient experience. That’s a time my obsessiveness helped; it’s the way I try to channel it today.

Finding balance...

I’m not a fan of the “hustle porn” a lot of industry folks push. I don’t think that people should make a habit out of losing sleep or time with family, for the sake of work.

On the other side of things, I never want a lack of effort to be the reason Ro fails. There are so many people that are smarter than me, or know healthcare better than I do. So whether this succeeds or fails, I want to know I couldn’t have worked harder. That doesn’t mean not sleeping, or not exercising, because those are things that help me perform at my best. I eat well, sleep 7-8 hours a night, make sure to spend time with my partner Cleo, and take Sunday night to hang out with friends, phone off.

The problem with “hustle porn” is that it’s all about suffering. Ultimately, I think that work can be joyful. Maybe that sounds silly, but I believe it. One of the great gifts of my personal life is that I love what I do. I can spend 15 or 16 hours a day on it, and feel excited to do the same the next day. I’m not saying those are the guidelines everyone should follow, but it works for me.

...but still having the #MambaMentality

With all of the above said, I think you’d be hard-pressed to find individuals, or groups of people who had an impact on the world without working incredibly hard.

After Kobe Bryan passed away, a lot of people talked about the Mamba Mentality. I love the spirit that embodies. It’s the notion that lots of people talk about wanting to be great, but only certain people are willing to do what it takes. When Kobe talked about it he made it clear he wasn’t asking for pity; he wanted to do those things, to do what was required to be great.

So while it’s true that I don’t have a lot of time for life outside of Ro, I’m ok with that. I don’t have much of a desire to do other things right now. If some people do, that’s great. I admire people with many passions and hobbies. But for me, right now, I’m happy to take this chance, and maybe be a little less well-rounded for the time being.

Digressions

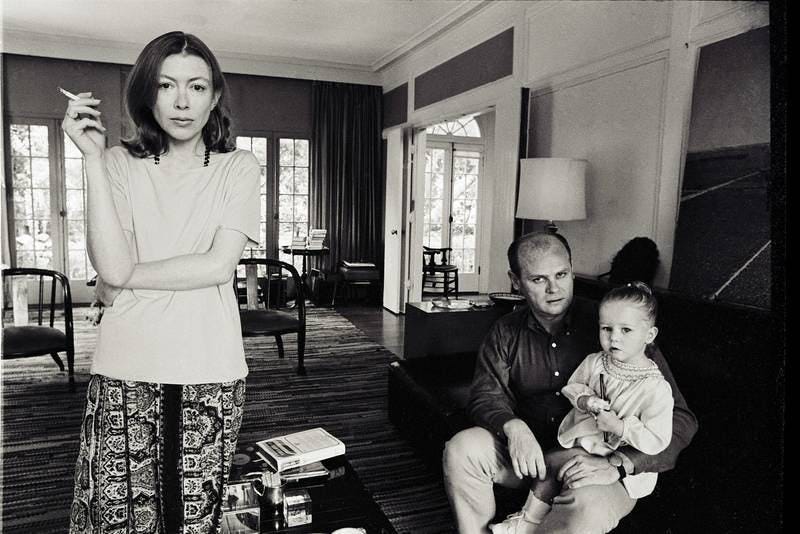

His favorite work of fiction or creative non-fiction

The Year of Magical Thinking by Joan Didion. It’s a memoir that unpacks the death of the author’s husband and daughter, both of which occurred in the same year. It’s fascinating to see someone with such intellectual horsepower, someone so painfully curious, observe grief. I’ve never read anything like it.

The best piece of advice he ever received

“When there’s doubt, there’s no doubt.”

That’s something Max Levchin said during a YC dinner and it’s really stuck with me. It makes so many decisions, decisions that might look difficult, crystal clear.

The last app or product he fell in love with

Superhuman is an amazing product. I really do love it. Apart from that, I recently got a Peloton which has been fantastic. And Overcast is my go-to app for listening to podcasts.

The moment he realized he was onto something special

Funnily enough, it was launch day.

You know one of the places where the “if there’s doubt, there’s no doubt” applies? Product/market fit. If you have to ask if you have it, you don’t. My co-founders Salman, Rob, and I have all worked at startups that didn’t find it.

At Ro, it was clear straight away. We didn’t know it would turn into the company we have now, but as soon as we launched our site and started treating patients’ orders, we knew we’d built something people wanted.