The S-1 Club | Rackspace rises again

Contributors

Brief

The cutthroat owners of Chuck E Cheese

Fanatical Experience™

Started from a garage, now we're here

What makes Leon Black happy

To the (multi)cloud!

"Marionette management"

Declining revenue but solid margins

"People rails"

The WallStretBets effect

TL;DR

Rackspace is returning to the public markets. Private equity firm Apollo Global took Rackspace private in 2016, saddling the company with $4B in debt and aggressively reorienting the product. Today, Rackspace is a services business with ~40% margins and $2.4B in revenue, of which 95% is recurring. The company hopes to be valued at $10B when it hits the Nasdaq with its new ticker "RXT." But with significant competition in the space, steep interest payments, and profit-maximalists at the helm, the company will need to execute perfectly.

Get involved

Before we get into the nitty-gritty, we wanted to take a brief moment to share how you can get in the mix. As we hope you know, the heart of the S-1 Club is discussion and collaboration. To that end, we'd appreciate your help in sharing this breakdown with other smart folks. We'd also love to hear your takes. Just respond to this email and we'll get back to you!

Entering the asylum

Welcome to 1 Fanatical Place. As the team likes to say, "you don't have to be crazy to work here, but it helps."

If that registered address doesn't scare you off, perhaps Rackspace's decision to trademark the phrase "Fanatical Experience" will. This is a company at pains to emphasize just how intensely they take cloud services. Though it's easy to get wrapped up in the company's wide-eyed, white-knuckle description of a business that hits like a sedative, there's a fascinating story beneath the marketing bravado.

In many ways, Rackspace feels like the cloud company that Time forgot. While AWS, Azure, and Google Cloud spent the last ten years guzzling glutamine and bulking up, Rackspace spent the latter years of the last decade slumped in an identity crisis. Were they a technology company or a consulting shop? Is this a software business or a services play?

Taken private by PE firm Apollo in 2016, Rackspace at least seems to know what they want to be today, or at least, how they want to be valued. The clue is in the name: "Rackspace Technologies." The catalyst to this transformation, this hopeful glow-up, is a familiar figure. If Rackspace spent the 2010s as a reedy teen, locked in the bedroom, goliath Apollo is the gym rat moonlighting as a pick-up-artist, telling the young gun to project confidence. With $77B in AUM and a roster of mainstream brands including ADT, Qdoba, and Hostess brands — along with the House of Terrors that is Chuck E Cheese's — Apollo had the muscle to get Rackspace into fighting shape. That came at a cost.

Another day at the Nightmare Factory | Mel

Though Rackspace boasts $2.4B in revenue, 95% of which is recurring, strong geographic penetration, and an elite customer base (in theory), there's a catch. The company is ~$4B in debt, thanks to Apollo's purchase and financial machinations.

That's the story that we hope to tell today. The tale of a company betwixt services and product, both bolstered and hobbled by private equity and its business model.

The transformation of the cloud

In 2006, Amazon changed the software infrastructure landscape by launching Amazon Web Services (AWS). It was the first large and accessible cloud computing platform. This seminal moment changed the enterprise landscape: before the cloud, businesses had in-house server hardware, software licenses, and a slew of IT professionals to manage it all. This on-premise infrastructure was inflexible and expensive. Cloud adoption made software architecture more flexible, cheaper to maintain, and easier to scale up and down.

AWS CEO Andy Jassy demonstrating how little he worries about Rackspace | The Information

An obvious win for cash-strapped early-stage startups, the cloud also benefited big businesses. Building on the cloud had several benefits. One of the main advantages of cloud computing is turning a fixed cost (pay upfront for physical data centers) and moving it into a variable cost (pay-per-use cloud computing). It also allowed employees to access company servers from anywhere, thus making them more productive (not just in the work-from-home sense, but also because it allowed for version control and access to lower-cost labor). Finally, the cloud ensured companies operated with best-of-breed infrastructure. It's not an easy technical problem to manage distributed information systems, let alone keep up-to-date on the cutting edge of computing technology. As a result, many companies have outsourced the headache, facilitating more robust and complex solutions.

Though the rise of cloud computing has played out publicly, Rackspace does a nifty job of outlining adoption over the past decade. In the early 2010s, cloud adoption was limited to early adopters. By the mid-2010s, businesses started moving to the cloud as they "focused on reducing costs and enhancing scale and reliability." Today, almost every company has either embraced the cloud or plans to do so. Rackspace's opportunity lies in servicing the transition and expansion, serving as a trusted third-party and helping companies navigate complicated offerings.

Jargon

A few favorite terms | Rackspace S-1

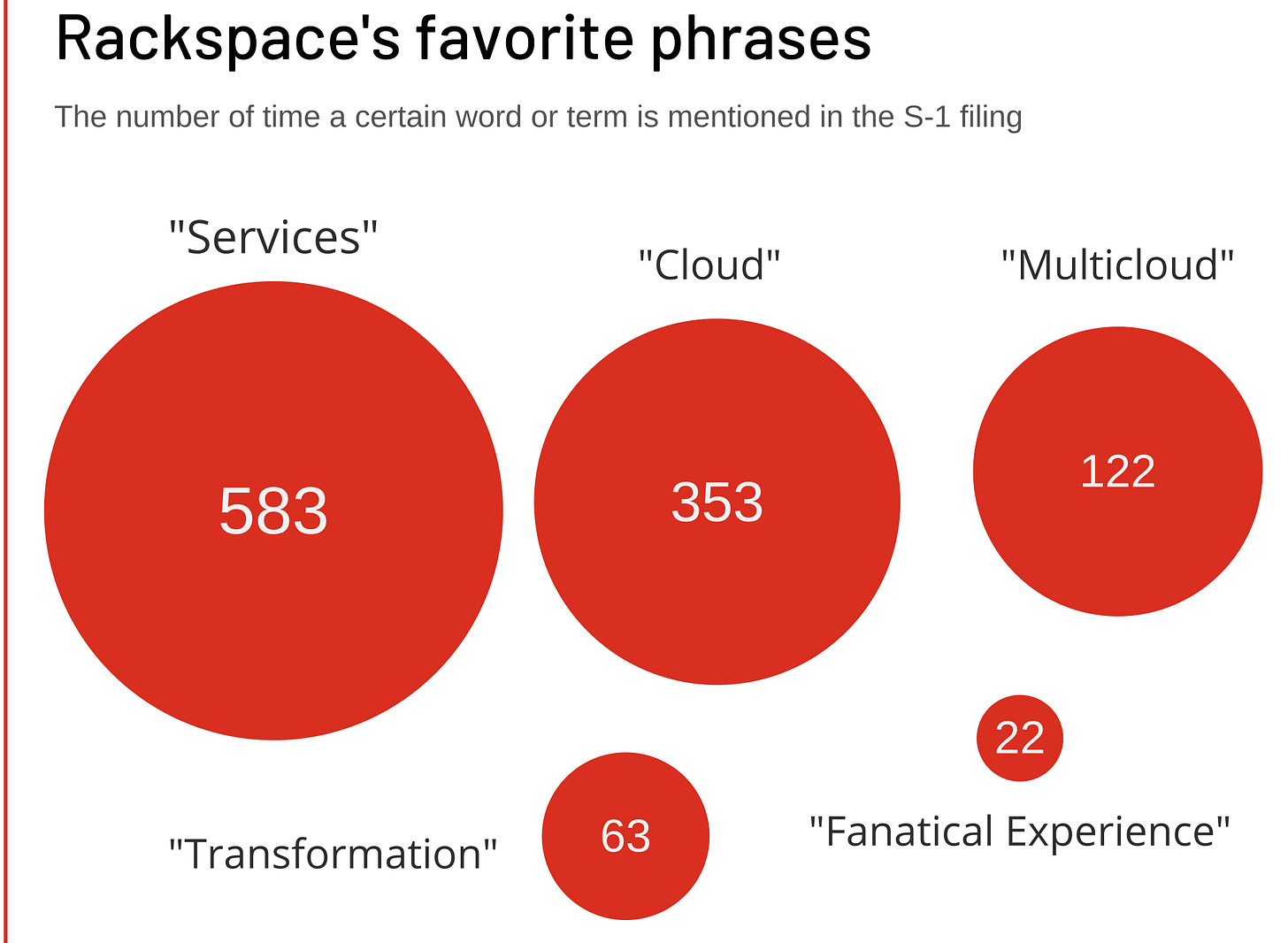

We're suckers for some good S-1 doublespeak and Rackspace delivers with aplomb. Fittingly enough, one of the company's most fustian passages is a description of itself.

We are a leading end-to-end multicloud technology services company. We design, build and operate our customers' cloud environments across all major technology platforms, irrespective of technology stack or deployment model. We partner with our customers at every stage of their cloud journey, enabling them to modernize applications, build new products and, adopt innovative technologies ... all wrapped in a Fanatical Experience.

So is Rackspace a technology business? Is it a services business? What is a "Fanatical Experience?" You can answer those questions by looking at these handy charts.

The ballad of Rackspace and Apollo

Origins

It's the classic Silicon Valley story, set in San Antonio.

In 1996, a young engineer, disenchanted with his college education, starts a business out of his garage. As a student of Trinity College in Texas, Richard Yoo had been pursuing a pre-med degree when he began Cymitar Network Systems to pay the bills. It was a dev shop really, helping customers build new web apps and taking on support for internet access and hosting. Much of the company's early days were focused on building a solution for customers to use credit cards online.

For its first few years, Cymitar's trajectory was modest. It was only in 1997 that Yoo brought aboard a co-founder, Dirk Elmendorf. He'd discovered Elmendorf was behind a "mind-blowing" online chess game and the two built a friendship. The next year Yoo added Patrick Condon, completing a trio of former Trinity graduates.

From left, advisor Morris Miller, Dirk Elmendorf, Richard Yoo, and Pat Condon | TechTonics

Condon's recruitment coincided with the company's first major identity crisis, an event that would become something of a theme across the business' 24 years of operation. Though the team's intent had been to focus on app building, they kept running into the same problem. Hosting, finding a way to bring their work to life on the web, remained a hassle that couldn't be easily outsourced. Instead of fighting against that friction, Yoo and Co. leaned into it.

In October of 1998, Rackspace was born. The new company focused on web hosting, running "state-of-the-art" data centers in Texas. That was coupled with the service that companies needed. The term "Fanatical Support" was minted to describe the company's commitment to the customer, presumably only after Yoo, Elmendorf, and Condon spent many a late night in front of a blackboard, underlining and erasing "Maniacal Service," "Unhinged Assistance," and, "Genuinely Psychotic Cloud Help."

Two years later, investors came sniffing. Norwest Venture Partners and Sequoia contributed to an $11.5MM round, which, according to Crunchbase, followed a $6.3MM seed after just four months. Open source firm Red Hat joined the round.

Rackspace feels far from innovative today, but on its path to IPO, the company showed admirable invention. In 2003, Yoo launched "ServerBeach," a low-cost, flexible service aimed at the hobbyist market. Instead of renting a dedicated server, technologists could get access to hosting when they needed it. The company spun out and sold ServerBeach the next year in exchange for a mere $7.5MM from buyers Peer 1. In the process, they frittered a lead in hosting services for smaller customers — but the creation illustrates Rackspace's critical role in pushing the industry forward.

Another experiment was "Mosso Inc.", a white-labeled hosting service from the company. This time, the sub-brand was kept in-house, becoming the basis for further cloud computing offerings.

IPO

The company very nearly never made it to the public markets. Rackspace had been courted by acquirers as early as 2001. One deal with Allegiance Telecom got particularly close. Yoo had been told by his lawyer he was about to become "a very rich man." The next morning, he received a flurry of calls. It was only once he finally picked up that he realized it wasn't well-wishers congratulating him; it was September 11, 2001. In the aftermath Allegiance's stock plummeted and the deal was off.

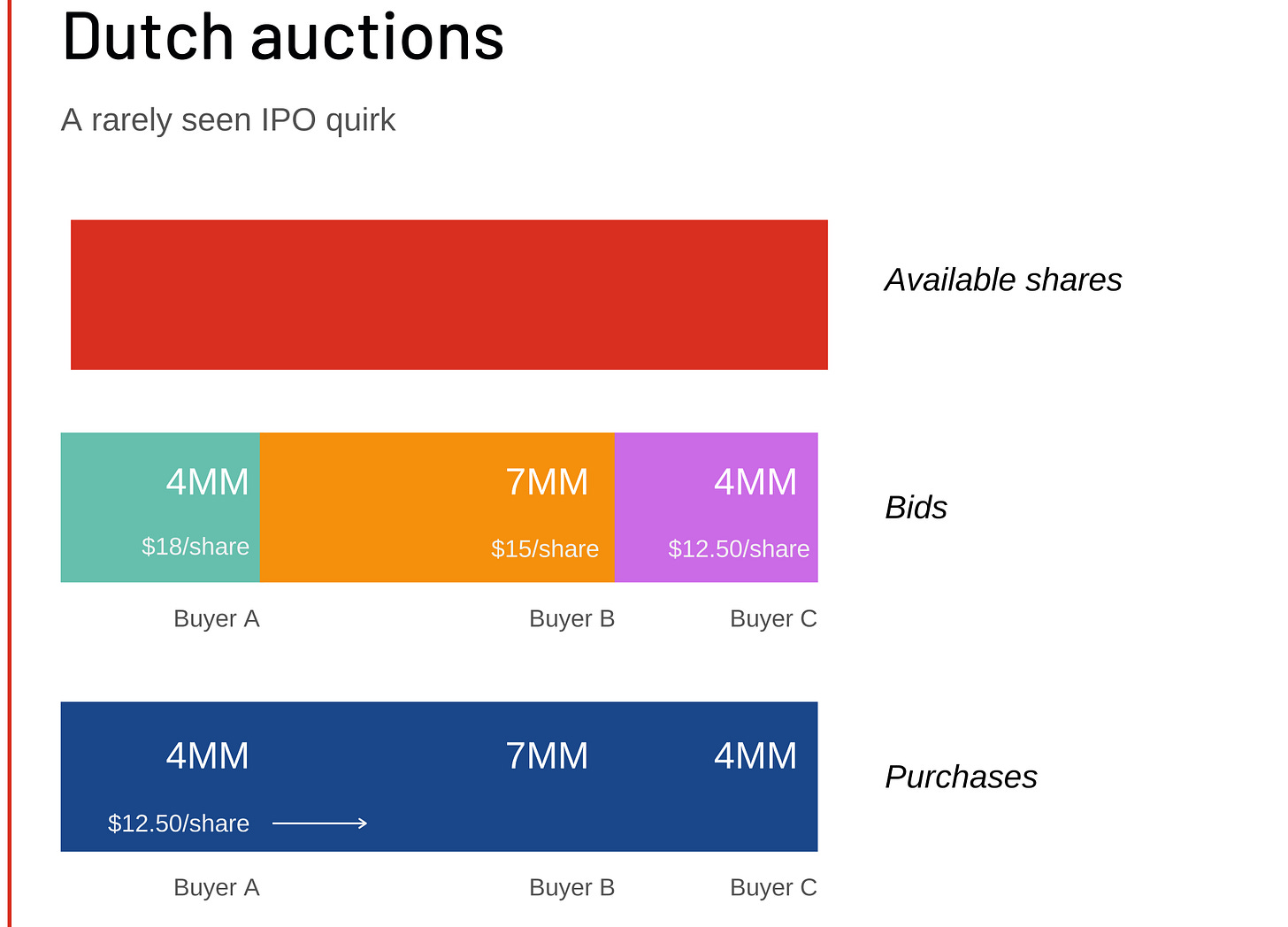

Eventually, of course, the business reached exit. Ten years after Cymitar became Rackspace, the company listed on the NYSE, choosing the ticker "RAX." In an uncommon move, Rackspace used a modified Dutch Auction to price its IPO, the same methodology employed by Google, and few others. In a Dutch Auction, buyers bid for a certain number of shares at a specific price. Once all shares have been bid on, the stock is allocated from the highest bids down, though each buyer need only pay the price of the last viable bidder. Confusing, right?

An example might help. Let's say Rackspace decided to sell 15MM shares, as they did in 2008. The process would go as follows.

Buyer A bids to buy 4MM shares at $18/share

Buyer B bids to buy 7MM shares at $15/share

Buyer C bids to buy 4MM shares at $12.50/share

It doesn't matter that Buyer D bid $10/share — the entire 15MM share offering is allocated at this point, and the price has been set. Because Buyer C was the last viable bidder, the price per share (PPS) opens at $12.50, with Buyers A, B, and C receiving their allotment at that price.

RAX did open at $12.50 a share, but that didn't help the company much. Within the first 24 hours, the stock had slumped to $10, with Red Hat selling 26% of its stake — not exactly an overwhelming vote of confidence.

Those that bought in would have been generously rewarded in the years to come. Rackspace rode the rise of cloud computing, growing at close to 20% a year at one point, and sending the company's stock price north of $80 a share. By 2016 though, growth had slowed with the stock below $20 and plateauing.

By the time Apollo Global Management announced a $4.3B takeover, Rackspace was growing at a mere 8% a year. The $32 price per share (PPS) that Apollo paid was a 38% premium on the current stock price and exactly the value at which the company had traded a year earlier.

After forfeiting a lead to AWS and others, Rackspace didn't seem to have a clear path forward.

The buyer

Leon Black is an enigma.

The son of the man behind United Brands Company (owners of Chiquita Banana) and a watercolorist, the Dartmouth philosophy graduate only turned to finance after considering careers in literature and film. Black's father, Eli Black, would later commit suicide, breaking the window of his office on the 44th floor with his briefcase, before falling to his death. The SEC had discovered that United Brands had paid a $1.25MM bribe to Honduran president Arellano in exchange for reduced export taxes on produce.

Leon Black looms over the Rackspace IPO | Artnet

As for Leon, despite the crisis of identity his father's death provoked, he continued rising through the ranks of Wall Street's largest firms. Beginning his career at Peat Marwick (the precursor to KPMG), Black made partner in just four years at Drexel Burnham Lambert, the investment banking partner to many of the 1980s corporate raiders.

After Drexel's collapse — precipitated by SEC investigations, botched deals, and a crashing junk bond market — Black founded Apollo in 1990. In the decades that followed, Apollo rose to prominence, growing its AUM to $323B by 3Q19 and producing a net return of 44% between 1999 - 2019. Much of that success arose from the firm's penchant for distressed investments, picking up struggling companies for depressed prices, imposing austerity measures, and selling them for a profit.

While we'll dig into the incentives of private equity institutions like Apollo in a moment, that's very much the playbook that Black and Co. have imposed on Rackspace. The company has been saddled with billions of debt, key management has been replaced, and the company Yoo built has rebranded itself yet again: in 2020, Rackspace added "Technologies" to its name, broadcasting how it hopes to be treated by the public markets.

IPO, again

By seeking to return to the public markets, Rackspace follows in the footsteps of Dell, Liberty, and Burger King. All rang the bell before being taken private, then returned to list once more.

This time, it will hope to carve out a more enduring foothold, though with Apollo still controlling much of the Rackspace's direction, it remains to be seen how much innovation we should expect from the firm that shed its initial founders long ago.

The incentives of private equity

When the word private equity is mentioned, what comes to mind?

The past few years have ensured that for most, some mix of these images flit across your brainscape: alpha males in slick suits, hatchets, machetes, the smoldering wreckage of beloved brands.

While those associations are not without cause, private equity does serve a purpose, at least in theory. At its best, private equity takes struggling businesses, takes on debt to give the company breathing room, catalyzes wholesale changes, then reincarnates the firm in a more robust form, either selling to another buyer or releasing it into the public markets.

The minds behind Blackstone's $14B payday | Fortune

The canonical success story is Hilton. In 2007, Blackstone took the hotel chain private, putting up part of the $6.5B in equity required. During the financial crisis, Hilton revenue fell 20%, making Blackstone's bet look foolhardy at first. But in the years that followed, performance improved, and by the time the company returned to the public markets in 2014, the firm had locked in a strong return. As shares have surged in the years since, that win has swelled to $14B, the most profitable PE deal in history.

Of course, things do not always work out so neatly. A big part of that is the fundamentally confrontational model at the heart of PE. To put a finer point on it, PE firms do not need the consent of the company they're buying to engineer a deal.

Firms employ "leveraged buyouts" (LBOs) to take their targets private. That involves taking on significant debt to make a purchase — often, the assets of the company being purchased are used as collateral. It's a little like a wrestler using his opponent's weight against them — your strengths become your undoing. It's attractive for the PE shop because less capital is required to make a deal happen, magnifying potential returns.

Give me an example

SuperAlpha Fund wants to buy Mom's Spaghetti Corp

Mom's Spaghetti is valued at $8B, including assets like factories and machinery

SuperAlpha cobbles together $1B of cash then goes to the bank

SuperAlpha asks the bank for a $7B loan. Since SuperAlpha will own Mom’s Spaghetti after the deal is completed, the deal is structured so that Mom's Spaghetti assumes the debt. The loan is then collateralized with Mom’s Spaghetti’s pool of assets.

SuperAlpha gets the $7B loan and buys Mom’s Spaghetti

Mom’s Spaghetti pays down the loan to the bank. SuperAlpha pays nothing. In the event of a default the bank seizes the assets of Mom’s Spaghetti.

Not all LBOs are hostile, of course (Rackspace's was not), but regardless, the purchase leaves the company in a very different financial position. Having assumed significant debt, the company is now on the hook for the high-interest payments necessary to pay the debt off. The bet the PE firm is making is that with operational changes, including layoffs, the company is able to become profitable above and beyond these new commitments.

It's a risky proposition and something of a tightrope walk. When successful, as was the case with Hilton, it can yield huge returns. Apollo's track-record is a further illustration of the appreciation investors may see. By and large, a high-powered PE firm would expect to outperform public equities by 4-5% in the long-term. Target internal rates of return are usually 20-25%.

But even the best funambulists fall, and PE firms have driven many iconic companies to an early grave. Toys R Us, Hertz, Neiman Marcus, and J.Crew all declared bankruptcy in soured PE deals. In total, 20% of LBOs lead to bankruptcies versus just 2% of the sample group of publicly traded businesses. Often, PE firms may not know much about the sector they're buying into, making recommendations counter to those with more experience. Furthermore, they're typically operating on a compressed timeline to meet their goal returns — a three-to-five-year hold is common. While PE firms don't see major returns in the event of a bankruptcy, they still get paid. Like venture capital, most firms operate with a "2 and 20" business model, earning 2% of AUM as their management fee, and clipping 20% of returns. For example, if a firm had the $554B AUM of Apollo, they'd snag $11.08B a year in fees even if every one of their deals flunked. (We imagine Apollo has a more convoluted fee structure). Over time, investors would leave the firm, but the model illustrates that incentives are only partially aligned.

Of course, often those left holding the bag for PE's machinations are employees themselves. To streamline their purchases, firms often make cuts to staff and benefits. As Brian Ayash, a researcher at California Polytechnic noted, "The community loses. The government loses because it has to support the employees. [Who wins?] The funds do."

The market

We may have Jason Segel and Cameron Diaz to thank for the introduction of "the cloud" to popular culture. In the disastrously received 2014 rom-com Sex Tape, a married couple learns they've accidentally uploaded their amateur clips to the web.

In the only scene we can remember from the trailer, Cameron Diaz berates Segel for failing to delete the tape to which Segel replies, "It kept slipping my mind, and then the next thing I knew, it went up! It went up to the cloud!"

When Diaz responds, "And you can't get it down from the cloud?", Segel snaps.

"No one understands the cloud. It's a mystery!"

Despite its foundational role in our lives online, cloud infrastructure remains mysterious, and frankly, fairly soporific. That doesn't stop it from being big business. Estimates vary, but Allied Market Research pegged the 2019 global market at $265B, hinting at the magnitude of the sector. That same report suggested the space could grow to $900B by 2027 — a strong 17% CAGR. Unsurprisingly, Rackspace has a more optimistic take. The company believes the market for managed cloud services will reach $410B in 2020.

These are hefty figures, but they mean little without context. To fully understand Rackspace's opportunity market, it's essential to narrow the company's preferred customer profile and associated suite of core services. Let's break it down.

As described in "Company History," Rackspace has traditionally provided hybrid cloud and co-location services to a range of enterprises, from SMEs to Fortune 100s. In addition to insanely dedicated customer service, they initially operated data centers of their own.

That's changed over the years as Rackspace grappled with increased competition from heavy-hitters like AWS, Azure, and Google Cloud. Today, the company has leaned into its service roots. In particular, Rackspace is honing in on the "multicloud" market. Furthermore, the firm's acquisitions of Tricore and Datapipe in 2017, both enterprise solutions, suggest a narrowing focus on the Fortune 100. Both of these decisions seem to make sense: since 2013, 80% of enterprises have adopted a multi-cloud strategy with 60% of those using a hybrid system — essentially, a dynamic mix of private and public clouds. This trend is only likely to continue, and big enterprise should require a more sophisticated set-up. Rackspace is jockeying to capture that increased spend.

While we're going to dig more into the product below, we mention this here because it informs Rackspace's realistic market opportunity. While Rackspace's market is undoubtedly large and growing, we doubt the opportunity is as gargantuan as the company claims. Though the global spend for cloud services may indeed surpass $400B in 2020, this global cohort of customers will budget only a fraction of spend on MSPs like Rackspace. Smartermsp.com estimates that enterprises will allocate only 14% of IT budget to the segment. Still, while far short of the broad $400B Rackspace identified, a relatively fragmented $56B 2020 MSP market opportunity remains sizeable.

The product

Whether you want to call Rackspace a services business or an MSP, ultimately, the company performs one critical task: helping clients manage their cloud environments. To do that, Rackspace provides constant support with almost zero downtime.

As discussed above, Rackspace has benefited from the tailwinds pushing companies from self-managed solutions to complex, multicloud offerings. Though they haven't been the primary beneficiary (hello, Bezos), they're riding the same macro-trends. Incidentally, the coronavirus pandemic has accelerated multicloud adoption as businesses look to adapt to remote work, and cut costs.

Below, we'll dig into Rackspace's legacy business, what the heck a multicloud is, the company's customer service offering, and the tech itself.

Public cloud

Before AWS blew up everybody's spot in 2006, Rackspace made its money hosting. By 2016, the firm had racked up 11 data centers, co-locating with several others. That was a capital intensive business with great margins, but it's a shrinking part of the equation today.

As competition increased, Rackspace failed to keep up. They still offer hosting servies through their "Public Cloud" product but the focus has very much shifted to services. This business segment is a reminder of the company's roots, but decreasingly relevant.

Multicloud

It does what it says on the box.

You probably won't be surprised to learn that "multicloud" means using more than one cloud solution to enhance performance, ensure redundancy and resilience, and provide for increased security, compliance, and governance.

Rackspace's role is to provide service to customers using this set-up. The company's cloud experts, aka "Rackers," help businesses figure out what cloud services to use, how to set them up and get the most out of the technology. Figuring out how to architect and run a multicloud solution can be complicated, even for organizations with plenty of resources. Rackspace helps.

Apps & Cross Platform (ACP)

Beyond multicloud, Rackspace calls out this business unit as another key segment.

The banal name doesn't offer much of a hint. What ACP seems to handle is managed services outside the multicloud. In particular, Rackspace provides professional help in the security and data markets.

Again, service is at the core of the business here. With that in mind, it's worth asking: is Rackspace's service any good? Despite its liberal use of "fanatical" in describing its quality, Rackspace's Net Promoter Score (NPS) looks rather hum-drum. The company recorded a score of 44, the average NPS for airlines. Interpret that as you will.

On Trustpilot, the company has an average rating of 1.5 stars from 46 reviews. G2's ranking is healthier: 4 stars.

Still, customers do not seem to be in love. One angry commentator cut to the quick: "No Long[er] Fanatical". We can only assume that prompted weeping and rending of garments at 1 Fanatical Place. (Ed: Maybe this was a confused short-seller.)

Serious shade | Trustpilot

It's worth couching these sub-par results — much of the negative feedback seems to come from old customers relying on the company's Public Cloud hosting service. As Rackspace focused on providing support for multicloud, support for basic cloud hosting seems to have degraded. Rackspace's failure to keep up with the Joneses created an almost abusively inferior solution. In one rather damning report, a customer notes that in switching from Rackspace from AWS Lightsail, the cost of service dropped from $380 a month to $15.

Across the multicloud and the ACP segment, Rackspace generated 85% of its revenue in 2019.

The tech

Beneath its service operation, Rackspace does have some technology, though it's definitely of the more incidental variety. The fact that the company explicitly highlights its "billing system", which delivers "an integrated single invoice for customers across all multicloud deployments," is illustrative of the scant power under the hood.

Beyond a nice invoicing solution, Rackspace professes to leverage automation and predictive modeling to improve the service offered. The company's MyRackspace portal and app are used by 200K users a month to manage accounts and submit support ticketing. Something called "AIOps" ostensibly uses machine learning to "enhance IT operations" while the company's API extends service delivery.

This doesn't sound like much, but there's some indication that it does drive bottom-line results. The S-1 notes that one of the priorities during the company's private stint was in building more automation to improve revenue per employee. Over 200 "technology tools, branded solutions, and accelerators" have been unified by the company to increase service efficiency. We'll talk more about this below.

That said, Rackspace bulls are unlikely to base their optimism on the company's software, even if it does provide operational advantages. Ultimately, Rackspace's strengths seem to lie in services, for better and worse.

The model

Rackspace makes money by selling expertise.

What begins as an initial assessment and strategic engagement with one of the company’s 6,800 Rackers often transforms into a recurring service offering. Multicloud contracts typically start with a 12-36 month engagement that is automatically renewed, though there are no cancellation fees after the stated period ends. Early cancellation fees are levied, though Rackspace notes they may not cover the cost of service.

As alluded to in the "Product" section, the company does operate a Public Cloud, though this is of diminishing importance. Billing for this product is on a usage basis with no cancellation penalties.

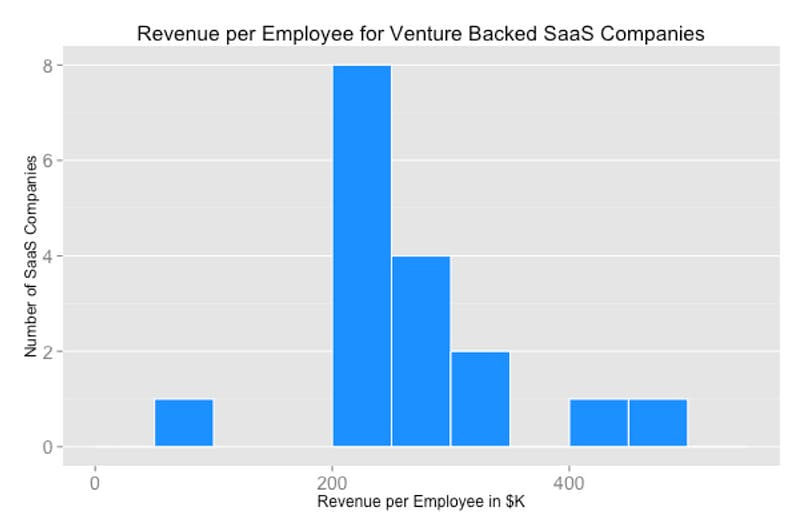

Returning to the service business, the automation we described above has yielded solid results when looking at revenue per employee. In 2018, Rackspace brought in $372K per employee, rising to $375K in 2019. That is presumed to outstrip competitors and is more akin to a SaaS business. Incidentally, SaaS companies invest between 80% and 120% of their revenue in sales and marketing in the first five years of their existence, while SG&A accounted for only 37.4% of Rackspace's revenue in 2019. This makes sense as they're a mature presence in the market now, and their efforts are directed towards retaining existing customers.

Rackspace's Revenue per Employee is SaaS-like | Tomasz Tunguz

As noted in the "Market" section, Rackspace is making moves to focus on larger companies. The S-1 explicitly notes the desire to serving enterprises generating $1B or more in revenue per year.

The company's ARR was $2.4B as of 2019, with net dollar retention of 99%, which is lower than average for recent Software IPOs. However, it's not completely fair to evaluate the company like a SaaS company with the majority of the revenue generated from the services they provide.

Unit economics

Rackspace's S-1 is pretty light on information related to customer cohorts and their growth. Nevertheless, we can get some sense of their unit economics based on available data.

The typical transaction looks something like this:

Rackspace convinces a company to choose it for its cloud needs. The Rackers rejoice. To make the sale, Rackspace had to spend money to get the lead, qualify that lead, and wine and dine the customer for multiple months. Finally, after everyone's been stuffed with ribeye and downed a few bottles of a daring little Rioja, Rackspace closes the contract.

While Rackspace doesn't break out its sales and marketing costs, the firm does disclose its SG&A spend. The company spent $250.9MM on SG&A from January 1 - March 31, 2019, a figure that dipped to $249.3MM in 2020, implying a total spend of $997.2MM for the full year. Advertising costs, which may capture some of the spend on sales and marketing, stood at $42MM in 2018 and $40MM in 2019. The first three months of 2020 saw a spend of $12MM, suggesting a spend of $48MM for the year.

In total, we expect roughly 80% of SG&A to be allocated towards sales and marketing. With that in mind, every ~$1 in sales and marketing Rackspace spends, it receives ~$0.8-0.95 in bookings. This has been increasing over time, which suggests that the efficiency of their sales and marketing efforts is improving.

Since Rackspace's gross margins are ~40%, the company effectively spends $1 upfront to get ~$0.32-0.38 in gross profits. Of course, customers continue to use Rackspace in future years, with the company earning recurring revenue. Quarterly revenue retention is 98%, which means that roughly 94% of revenue is retained on a yearly basis.

If we assume Rackspace retains customers for 17 years on average (as implied by a 94% retention), and use a discount rate of 10%, we get an LTV/CAC ratio of 2:1. That's pretty good, but not great with something north of 3:1 considered to be a solid benchmark. Again, there's some cause for optimism, given the firm's improving marketing efficiency.

We can also calculate a payback period for Rackspace on its sales and marketing efforts. Since $1 spent leads to $0.32-0.38 in gross profits, which retain at 94%, their payback period is roughly three years. This is sub-optimal, with 12-18 months a favorable benchmark.

All told, Rackspace's unit economics are passable without offering much cause for elation. Given the competition in the space and low gross margin structure, that's not terribly surprising.

Management team

The success of certain management teams can often be framed as a question of evolution. The best learn to zig and zag over the course of a business's lifespan.

The tech sector witnessed Zuckerberg's adept transformation of Facebook from a desktop company to a mobile one. Wix founder Avishai Abrahami helmed the website builder to new prosperity by morphing the company from Flash to HTML5. These executives (often the founders themselves) evolved to face the challenges of their particular business.

But for every story of evolution, there are tales of chopping and changing, cutting losses, and ousted leadership. Rackspace offers a fascinating look at the stories we don't hear in boardrooms, press, or rosy tweetstorms about operators who faced hardships and powered through. In many ways, Rackspace's management is a case study of the power of corporate governance and voting power of outsized shareholders (private equity) to move around operators (again and again) in a bid to find turnaround success. This is Marionette Management.

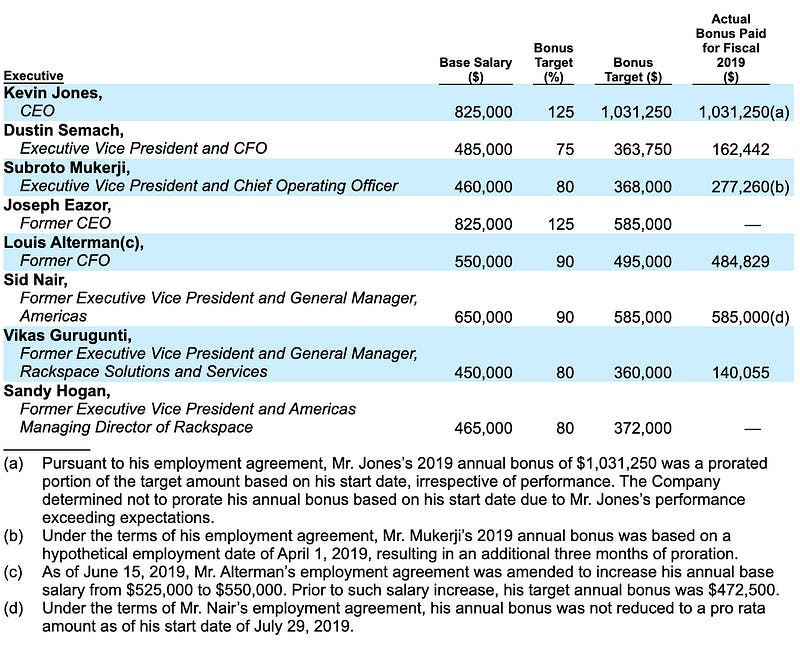

In the last few years, Rackspace has employed three CEOs. The man currently at the helm is Kevin Jones. He joined Rackspace in April of 2019, meaning he's been in the job for a mere 15 months, but there's a fascinating amount of information that connects Jones to his direct reports. He recruited many of them at previous gigs or worked alongside them. There's a particular connection to DXC Technology, a business that's eerily similar to Rackspace's services offering today. He also has a pretty remarkable comp package with a ton of incentive-based kickers.

Jones may be the person who is most visible to shareholders today, but a lot of the strategy he's executing was started by Joseph Eazor. Alongside Apollo, Eazor led the transition away from competing with AWS and Google Cloud and towards managed services for the multicloud. Eazor was at Rackspace for two years (!) before Jones started, tasked with three goals, according to an interview from June of this year:

Secure the best management team

Create impactful, transformational programs

Create a management system to pull in voices from all around the company. I like to call it a corporate operating system. (Ed: we won't dive into this goal, as we're not sure whether it was written by Jones or an AI).

Jones's ability to recruit (a key task for any executive) is on display in this S-1, achieving what appears to be his first goal. Of the 11 named executive officers, almost 50% worked alongside Jones at DXC Technology or Hewlett-Packard. That's impressive, especially considering the war for talent within Rackspace's domain.

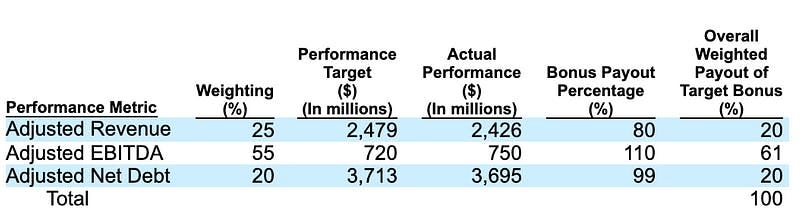

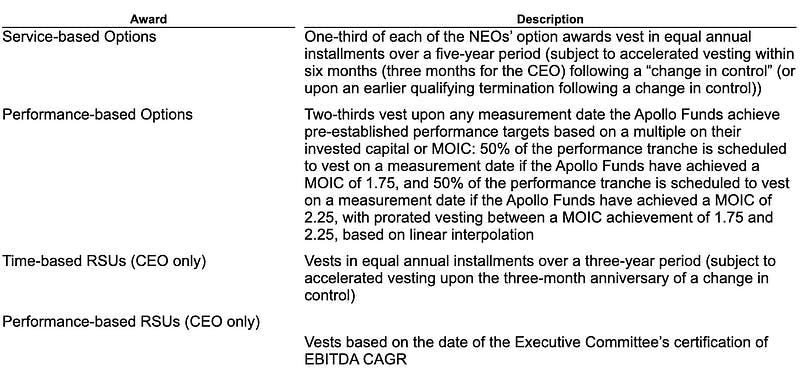

With regard to the second goal, Jones has clear incentives to manifest this vision beyond good PR: there's a hefty payout for him and his direct reports if the evolution of Rackspace continues. We can understand why by looking at incentive awards outside of cash compensation in the S-1, specifically explicit financial targets set forth by Apollo:

"EBITDA rules everything around me" — Kevin Jones, probably | Rackspace S-1

"Exceeding expectations" | Rackspace S-1

Incentives to be long-term greedy | Rackspace S-1

Jones can receive an additional $28MM in equity if he ensures a certain multiple on invested capital (MOIC) for Apollo. That's 26x his cash compensation. His team stands to benefit, too.

Unlike other S-1's we've analyzed, we've spent a lot of time on one person. That's not an accident: this isn't a "traditional" software IPO where a founder CEO is leading the company, has super-voting shares, and each of his or her lieutenants could be CEOs-in-the-making. What Rackspace illustrates is radically different: a company controlled by a single shareholder (Apollo), dictating how strategies get implemented, and who does the implementing. Despite their protestations, the hands behind the marionettes are motivated less by product development and customer obsession than ruthless cost-cutting and profit maximization.

Investors

If you've read up to this point, you'll know that Rackspace is primarily owned by Apollo, but there are other PE firms in the mix. While Apollo holds 78%, ABRY (13%) and Searchlight (7%) hold significant stakes. Management collectively controls just under 1% of the shares outstanding.

In keeping with the modern private equity model, that ownership isn't just ownership; it's also control. There are basically two ways private equity firms exercise control over the companies they own:

The obvious: PE firms specialize in recruiting management teams as we've discussed, reorganizing and streamlining companies, and using financial engineering to minimize the company's cost of capital. They'll concede this— and in that exact order, while critics would reverse the order and argue that private equity is mostly about levering up, not slimming down, the companies with which it's involved.

Private equity firms also charge their investees fees. For example, Rackspace has a management consulting agreement with its PE owners, in which it pays 1.5% of annual EBITDA. This runs Rackspace around $13m-$15m each year. The PE owners also get a 1% cut if Rackspace makes an acquisition.

Why would the PE companies, which own 99% of Rackspace, require Rackspace to pay fees? The S-1 is vague on the subject, noting the fees in question go to "Apollo," the company that manages the private equity funds, not to the Apollo Funds that own the stock. In other words, it's a transfer of money from Rackspace (owned by a partnership that pays Apollo Management 20% of the upside) to Apollo Management itself (which gets 100% of the upside).

These consulting agreements expire once Rackspace IPOs, so they won't affect shareholders' outcomes. And Rackspace helpfully excluded that cost from Adjusted EBITDA, so the underlying trend in the business will be clearer.

After the IPO, Apollo's control loosens a bit, but they're still at the reins. A series of investor rights agreements give Rackspace's current investors the right to continue nominating directors until they've sold half of their shares. Rackspace also can't change certain parts of its corporate governance, or raise funds past a low limit, without Apollo's approval.

At one level, this fee structure is a sneaky way to turn a 20% interest in a set of cash flows into a 100% interest. But the limited partners in PE funds are sophisticated investors; for many of them, the entire job consists of looking for ways to get a higher return, and pushing back on excess fees is a safer bet than finding a better fund manager. PE fundraising is a repeat game, too; the big institutions like pensions and college endowment funds will be considering the next vehicle Apollo raises, and if the fees are truly excessive — or truly misleading — Apollo will miss out on more fee upside from lost assets than they earned from a higher take-rate.

So a better interpretation is that this fee structure reflects the maturity of the businesses private equity companies buy. Venture capitalists try to help their portfolio companies for free and expect to get a return from equity appreciation. If the company you're funding is three people working out of an apartment, it's hard to extract cash for consulting agreements but comparatively easy to offer services in exchange for a bigger piece of the round. Some venture funds have pretty high overhead because of all the add-ons they offer — recruiting, PR, marketing advice, introductions to potential business development opportunities, and mini-conferences.

And there's not a huge substantive difference between cash fringe benefits and intangible benefits. When a company does something unprofitable but cool, like committing to zero emissions, taking a costly side on a public issue, launching a new product that sounds cool to the CEO but crazy to everyone else, it's also a wealth transfer from shareholders to the people who control the business. It's just that only one side of the ledger is measured in dollars. Since investors care about the costs they pay more than the benefits someone else gets at their expense, the exact form doesn't matter; controlling a company is a perk and a valuable one. Some people extract that value through intangible benefits. Private equity companies prefer cash.

Financial highlights

A company's financial statements tell a multi-year story. For Rackspace, this story is long, technical, and, to be honest, filled with periods of relative boredom. To tell it all would require more of your time than we are prepared to take. Think of this section as the "Blinkist-for-financial-statements." With that in mind, there are three crucial subplots to follow.

First, we need to explore the shifting product mix, from high capital intensity hosting and co-location to more efficient cloud services. This re-packaged core offering drives our next two key subplots, revenue growth, and margin dynamics (or lack thereof). Finally, we'll touch on the company's debt.

The transformation

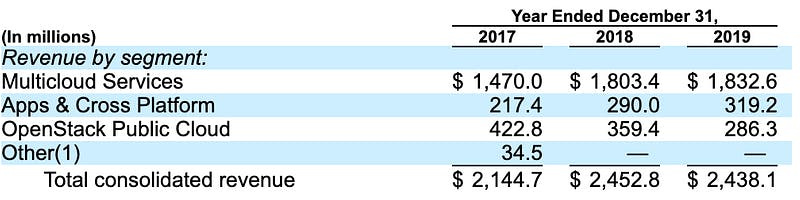

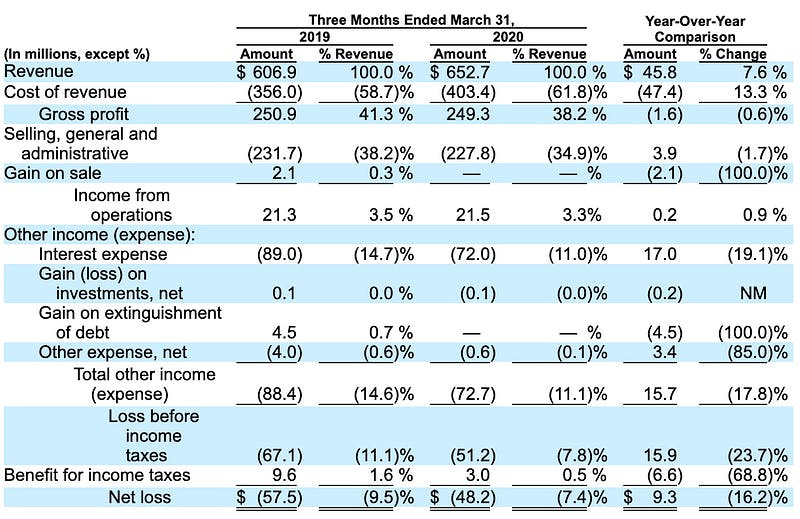

As mentioned previously, Rackspace has transformed the core business from a cloud provider to a cloud managed services provider. Why? Management (and Apollo) believe that outsourcing Public Cloud and hosting to 3rd parties while shifting to a headcount-based service model will drastically decrease both capital expense (CAPEX) requirements and operating costs (OPEX). Let's take a look at the revenue breakdown for the most recent quarter ended March 31 2020:

Rackspace S-1

Rackspace S-1

The new "core revenue" consists of "Multicloud Services and Apps & Cross Platform" sales. The Public Cloud is now a legacy revenue line item, which management has not actively marketed since 2017. At the close of 2017, the core segment accounted for 78% of the revenue mix. However, by aggressively selling and up-selling these segments to enterprise, management has succeeded in growing core revenue to over 90% by the close of 1Q20. Has this had the desired effect of decreasing CAPEX and OPEX?

Rackspace S-1

Selling, General and Administrative costs (SG&A) are trending nicely. Annual costs in 2017 came to $942MM, while the annualized 1Q20 SG&A of $908MM represents a decline of 3.6%. So, positive news on that front. Unfortunately, Rackspace has not realized similar savings on the CAPEX front. The last full year of data showed CAPEX up to $209MM from 2017. It is an improvement on 2018, however, which saw CAPEX of $348.1MM, a puzzling expansion.

With the above in mind, we should be careful extrapolating insight from only a few data points. Management is still investing heavily to transform the underlying business model, which will undoubtedly strain CAPEX for future periods. Over the next few years, Rackspace will hope to capital expenditures trend downwards.

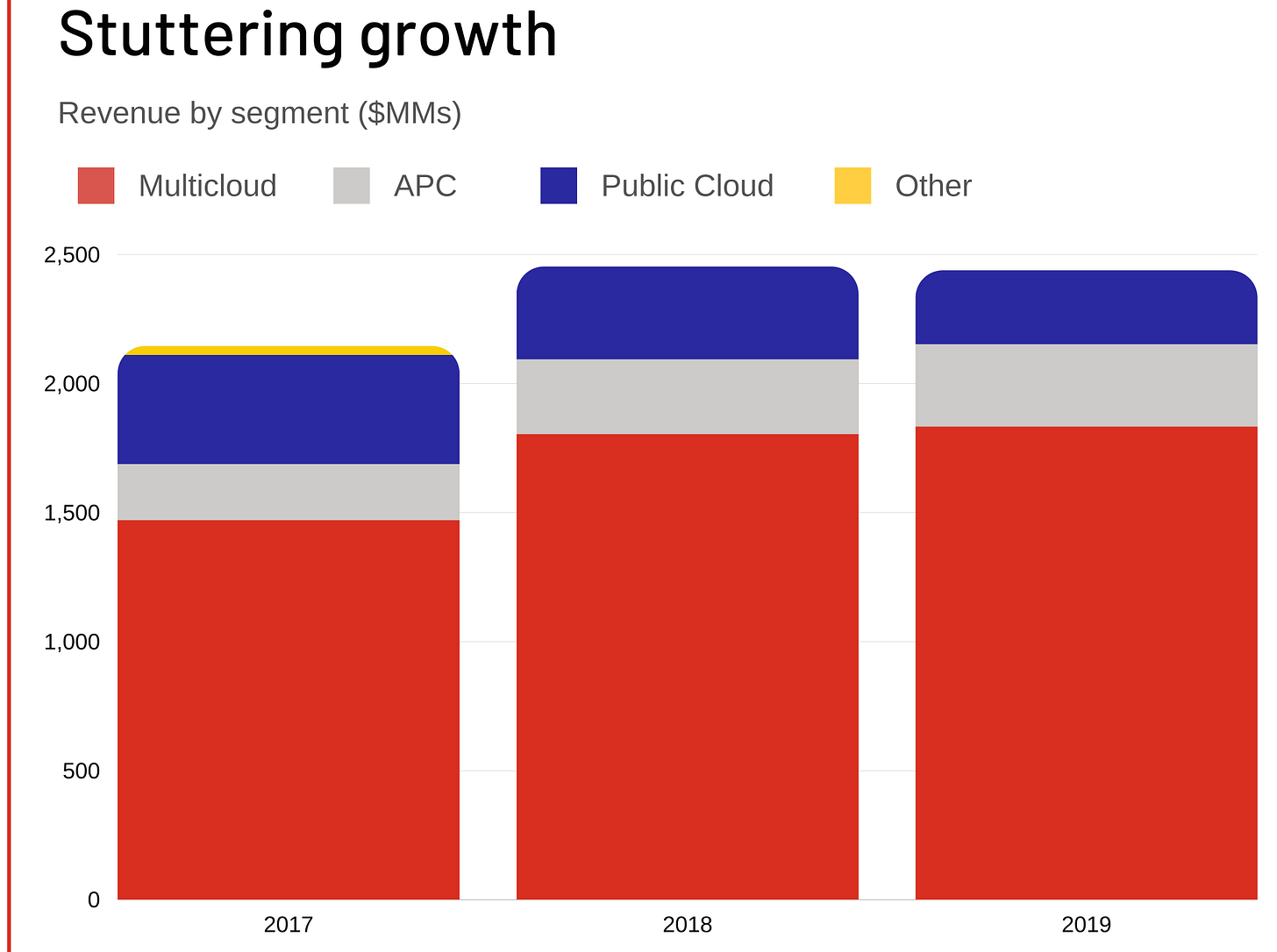

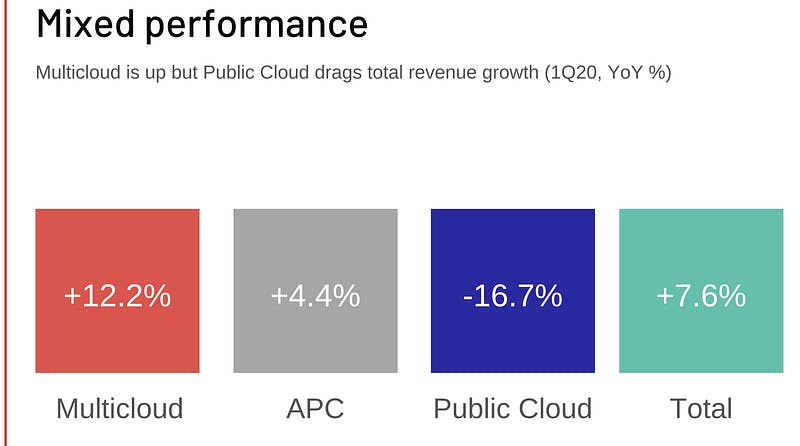

Revenue growth

Our second subplot: revenue growth. In 1Q20, "Multicloud Services" was up 12.2% YoY, while the "Apps & Cross Platform" segment rose 4.4%. But while this core segment grew by a combined 11% combined, legacy Public Cloud revenue decreased 16.7%. This dragged total revenue growth down to just 7.6%. Should investors be concerned? Not necessarily.

Rackspace S-1

Rackspace is actively managing the decline. As it moves away from Public Cloud services, revenue should be expected to decline. Moving forward, you can almost think of the Public Cloud product as both an internal financing solution and a sales channel. The unit provides a monthly cash allowance as well as offering quick access to an enterprise customer base with growing cloud needs. Rackspace is then able to reinvest legacy profits into the core business. For those that wish to keep track of the company over the next few quarters, core revenue growth may be higher signal than total revenue growth when assessing whether the company's strategy is playing out as planned. Stay tuned.

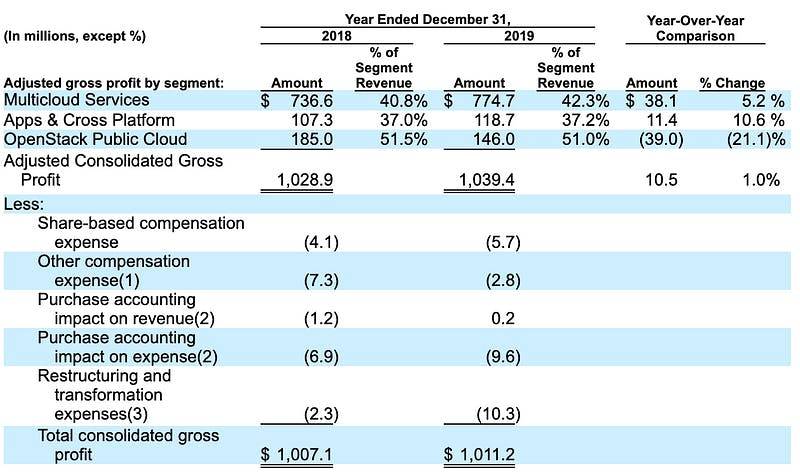

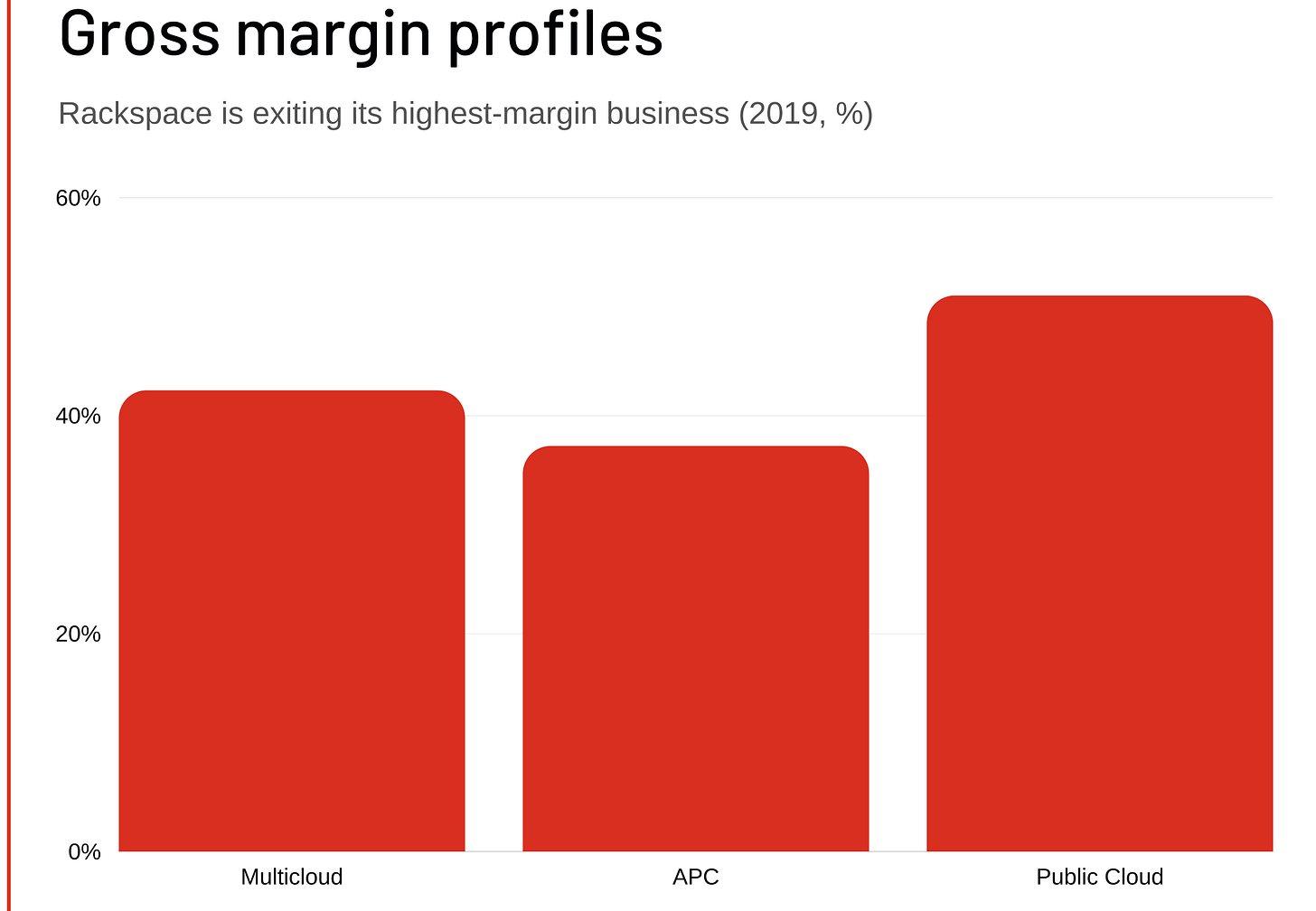

Margins

On to our third subplot. Let's dissect margins in light of the core segment shift. Reviewing the figure below, it becomes immediately clear that Rackspace has made a tactical decision to exit a relatively high margin, competitive market, for a lower margin, more fragmented one.

Rackspace S-1

As you can see, Public Cloud commands a 51% gross margin, far higher than the core segment revenue items. For comparison, "Multicloud Services," which accounts for 75% of total revenue, generates a 42% gross margin. However, Rackspace's Public Cloud offering competes with the titans of the cloud industry: AWS, Azure, and Google. By transitioning to an MSP model, Rackspace is preemptively throwing in the towel, conceding the market to these more established incumbents, and attempting to dominate the lower-margin service market. AWS, Azure, and Google have transformed from rivals to confederates.

Rackspace S-1

So, the Rackspace story is not one built on promises of near term margin expansion. Nor is it built on rapid growth, given the difficulties of scaling a headcount-based service model. Looking ahead, we expect margins to remain at ~40% or lower as higher-margin Public Cloud contracts roll-off.

Debt

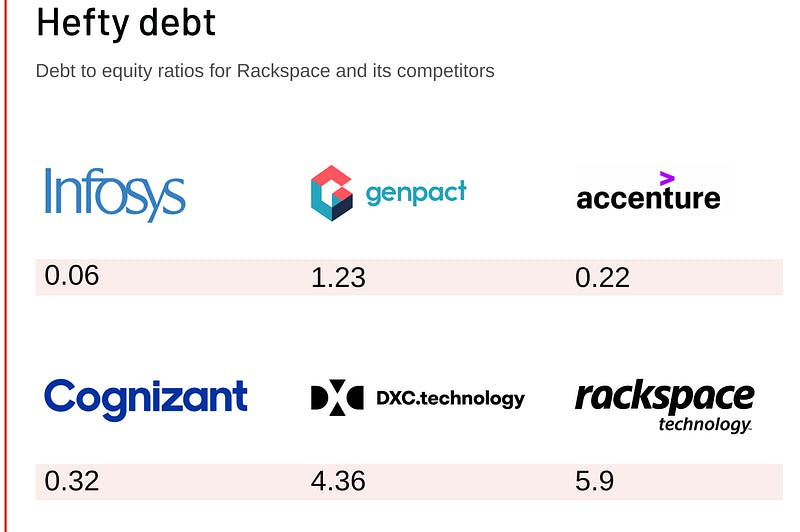

Rackspace has certainly...racked up some serious debt. (High-fives all-around at S-1 HQ). The company's $3.9B in the hole, relatively constant from 2018 to the present.

Incidentally, Rackspace cut cash holdings from $254MM at the end of 2018 to $84MM at the end of 2019 while accounts receivables shot up from $260MM to $350MM in the same period. Debt to equity for the company is currently sitting at 5.9x.

Unfortunately, none of the cloud service comps (AWS, Azure, GCP, etc.) break out their balance sheets, so we can't understand how those specific businesses are capitalized. Rackspace is heavily burdened with debt in comparison to their direct competitors:

Rackspace S1 and Gurufocus

We'll dig more into Rackspace's valuation and competition later, but a quick look at the numbers illustrates one of these is not like the other. While DXC has the steepest debt to equity ratio of competitors, Rackspace is comfortably in front.

That's worrying to the extent that debt adds risk to a business. Interest is fixed, meaning that if sales were to fall, payments would snag an increasing proportion of revenue. And though a business can make changes operationally — cutting staff, reducing rent and driving down COGS — there's nothing you can do about interest payments save filing for bankruptcy. In that scenario, since debt sits at the top of the capital stack, debtors would be paid before equity holders received any compensation.

In summation, investors looking for the next big cloud technology company are unlikely to be sated by Rackspace. They might also worry about the vulnerabilities such a significant debt might have on the company's future prospects. But if they believe there's potential in owning the service rails of an exploding sector, Rackspace boasts stable top-line expansion, and comparatively strong 40% margins.

Valuation

So what is Rackspace worth? As we noted, Apollo purchased the company for $32 a share at a $4.3 billion valuation.

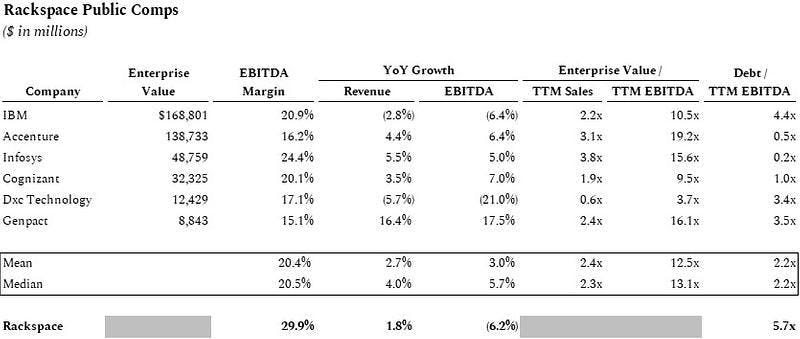

There are a few other public companies that operate in the same cloud services sector, providing a solid competitive set. We think these six technology service companies are most relevant: Accenture, Cognizant, Infosys, Genpact, IBM, and DXC Technology Services. (Remember them? CEO Jones is an alum). Many of these are listed as competitors on page 21 of the S-1.

Company filings via Koyfin. TTM represents most recent 12 months. YoY growth compares TTM with TTM one year prior.

Reuters reported that people familiar with Rackspace are looking for a $10B valuation. Rackspace reported $2.48B in 2019 sales and $742.8MM in adjusted EBITDA. A $10B valuation would imply a revenue multiple of 4.03x with an adjusted-EBITDA of 13.5x.

Considering the competitive set, this isn't totally unreasonable. DXC drags down the mean and median with degrading top and bottom lines, and the fact that IBM is a monolithic mishmash of multiple businesses makes it tricky to parse.

It's worth reiterating something we highlighted earlier: Rackspace does have a very different debt to equity ratio. That may not matter too much, though it's reasonable to think some investors might get scared off by the added risk.

Ultimately, these players are riding the same macro-trends as Rackspace. Only time will tell whether the cloud's growth can carry the company to a favorable valuation.

Competition

According to its S-1, Rackspace competes with the "in-house IT departments of its customers", "global IT systems integrators", "cloud service providers", "regional managed service providers", and "co-location solutions agencies". In other words, any company that develops or supports work for the IT manager.

As the Rackspace business evolved from a technology company to a managed service play, it's important to understand where and how this change occurred. As an enterprise customer, choosing what type of cloud solution and how to implement it can be daunting, so it shouldn't be a surprise that the way Rackspace's peers compete is to capture attention through advertising — often witty taglines.

IBM: "Let's Put Smart To Work"

DXC Technology: "Thrive Together"

Accenture: "Leading In The New"

Infosys: "Navigate Your Next"

Rackspace: "Solving Together"

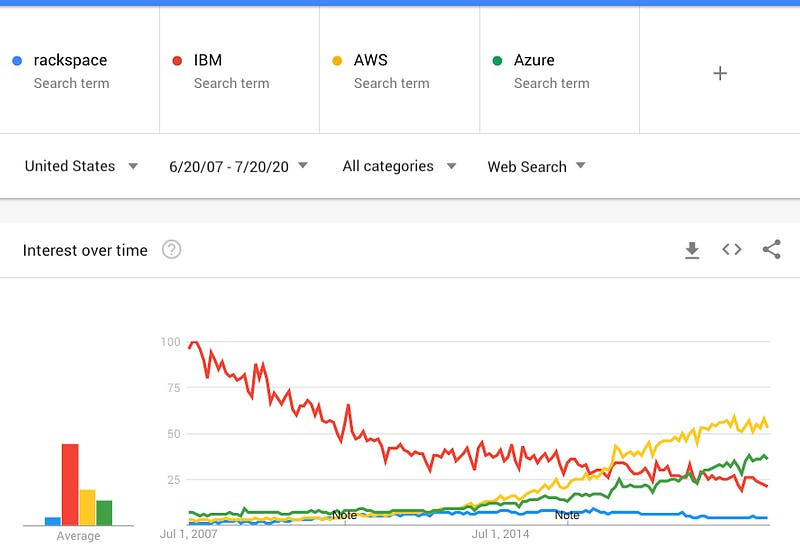

Despite these slogans, competing with the likes of Amazon or Microsoft has been difficult. Look no further than Google Trends over the last ten years and the shift to cloud software:

Waning relevance for Rackspace and IBM | Google Trends

Although companies can buy AWS, Azure, or Google Cloud directly, Rackspace figured out that not every company has the internal resources (and strengths) to adapt to the cloud transformation. This is why you see taglines from similar companies discussing change, leading, or navigating. It's all about movement in order to sell services on a recurring cycle.

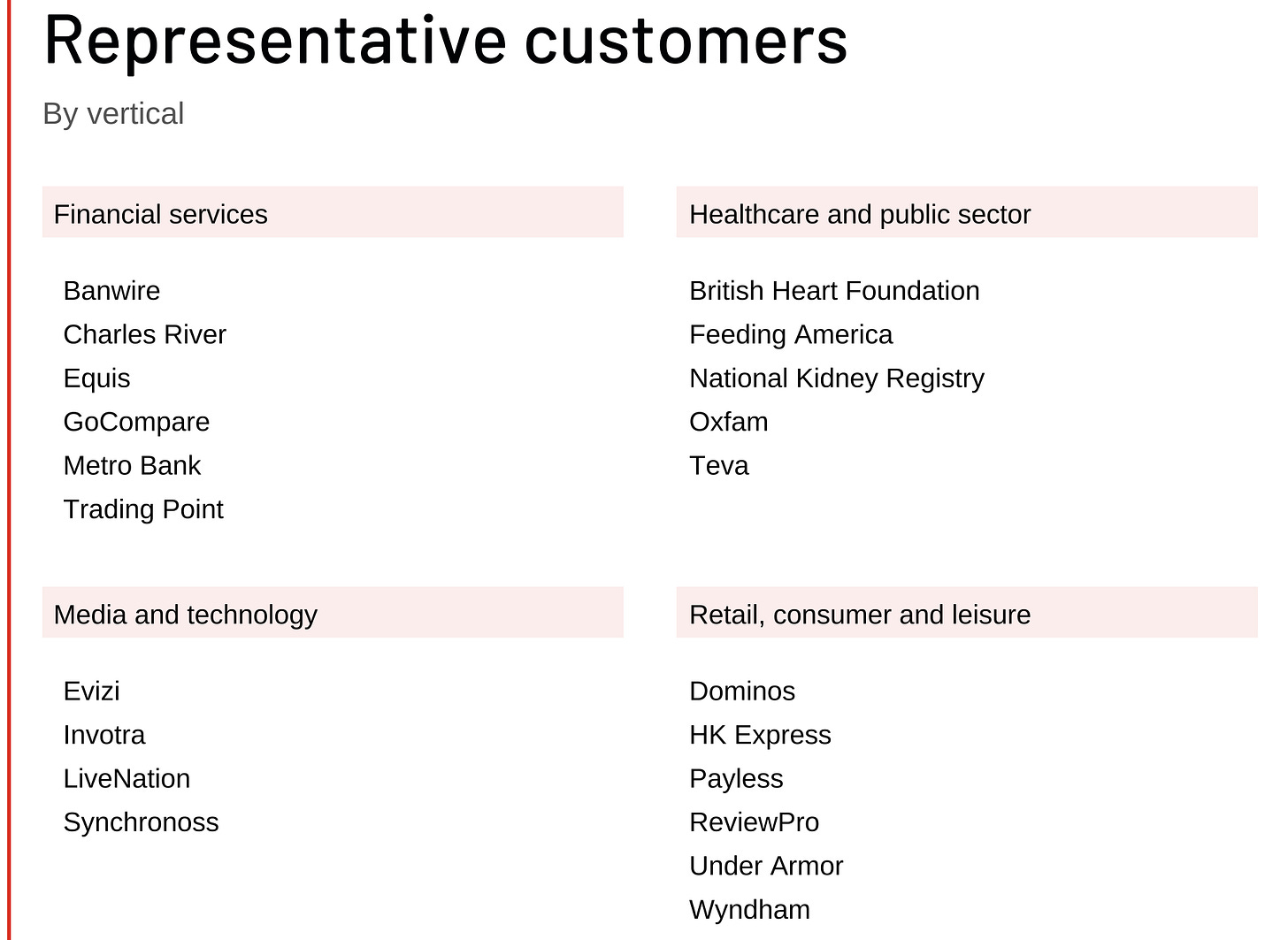

What's interesting about Rackspace's position in the market is that it was at one point a true technology company but has now become a "cyborg" (does anyone remember Groupon's infamous roadshow presentation on this topic?). In many ways, this allows Rackspace to authentically speak to customers who are managing shifts from on-premise solutions to the cloud — especially large, sleepy enterprise customers managing significant technical debt. Rackspace's customer base isn't necessarily the most innovative cohort:

Rackspace S-1 and Rackspace.com

Growth path

There's plenty about Rackspace that raises an eyebrow, but it's clear why some might think there's a play to be made. If you believe that every company is becoming a technology company (in some respect, at least), the cloud should continue its insinuation into corporate infrastructure.

Though AWS and others will be best positioned to provide the technology itself, Rackspace may have a chance to own the service layer. In that respect, Rackspace could become the "people rails," potentially a lucrative (if lower margin) segment to own.

COVID-19

In referring to the effect of the coronavirus, Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella said, "We've seen two years' worth of digital transformation in two months." Rackspace stands to benefit as cloud transformation efforts accelerate. The company's remote, tech-enabled delivery model has ensured minimal disruption to operations.

On the flipside, SMBs were particularly impacted by the coronavirus and may be looking to cut spending across the board. Products geared towards this audience, like Rackspace's Public Cloud, may take a hit.

Ultimately, it remains to be seen how the coronavirus impacts Rackspace, if at all. Given the recurring revenue nature of the business, any impact (either higher churn or increasing customer spend) may take a few quarters to show up. The company's decision to offer customers contract extensions on better payment terms, and secure better terms from vendors should be seen as a safeguard rather than an emergency measure.

Why now?

Private-equity firms like Apollo hold ample funds for new investments, but little for shoring up companies bought more than three or four years ago. Of all the dry powder in the buyout industry, about 85% is earmarked for funds raised from 2017 to 2019, according to an analysis by the investment and consulting firm Cambridge Associates. Accordingly, Apollo has been looking for an opportunity to IPO Rackspace for two years, per Reuters.

Perhaps this is the greatest impact of the coronavirus: it has presented a gift-wrapped opportunity to list.

Apollo hoped to take Rackspace public in 2019, but the company's head-scratching slowdown paused plans. The US cloud computing market grew from $101.4B in 2017 to $266.0B in 2019 while Rackspace shrank, dipping from $2.45B in 2018 revenue to $2.44B in 2019.

A noticeable uptick in Q1 2020 has reopened the door. US cloud services continued to rise, growing 37% YoY to reach $29B. Thankfully for Apollo, Rackspace is along for the ride this time. The company generated $652.7MM in 1Q20 revenue, up 7.5% from 1Q19.

With growth underway again, Rackspace is riding three trends into the market:

The coronavirus-related shift to the cloud, particularly for its target customers

Strong performance from peers

A friendly IPO market

To the cloud!

To hammer home Nadella's point — when the coronavirus hit, being in the cloud became a necessity overnight. On-prem servers make less sense when none of your people are on-prem. Most of the companies that have the internal capability to migrate to the cloud on their own had already done so, years ago.

The companies that planned to make the transition eventually, maybe in the next five years, are the companies that don't have the capability to do so in-house, particularly in a condensed time frame. Think J.Crew, Luxottica, Ulta Beauty, Under Armour, and Wyndham — all Rackspace clients.

Like Netflix and Zoom, Rackspace is pulling many quarters' or even years' worth of demand forward, which gives Apollo an ideal window to cash in.

Strong performance from peers

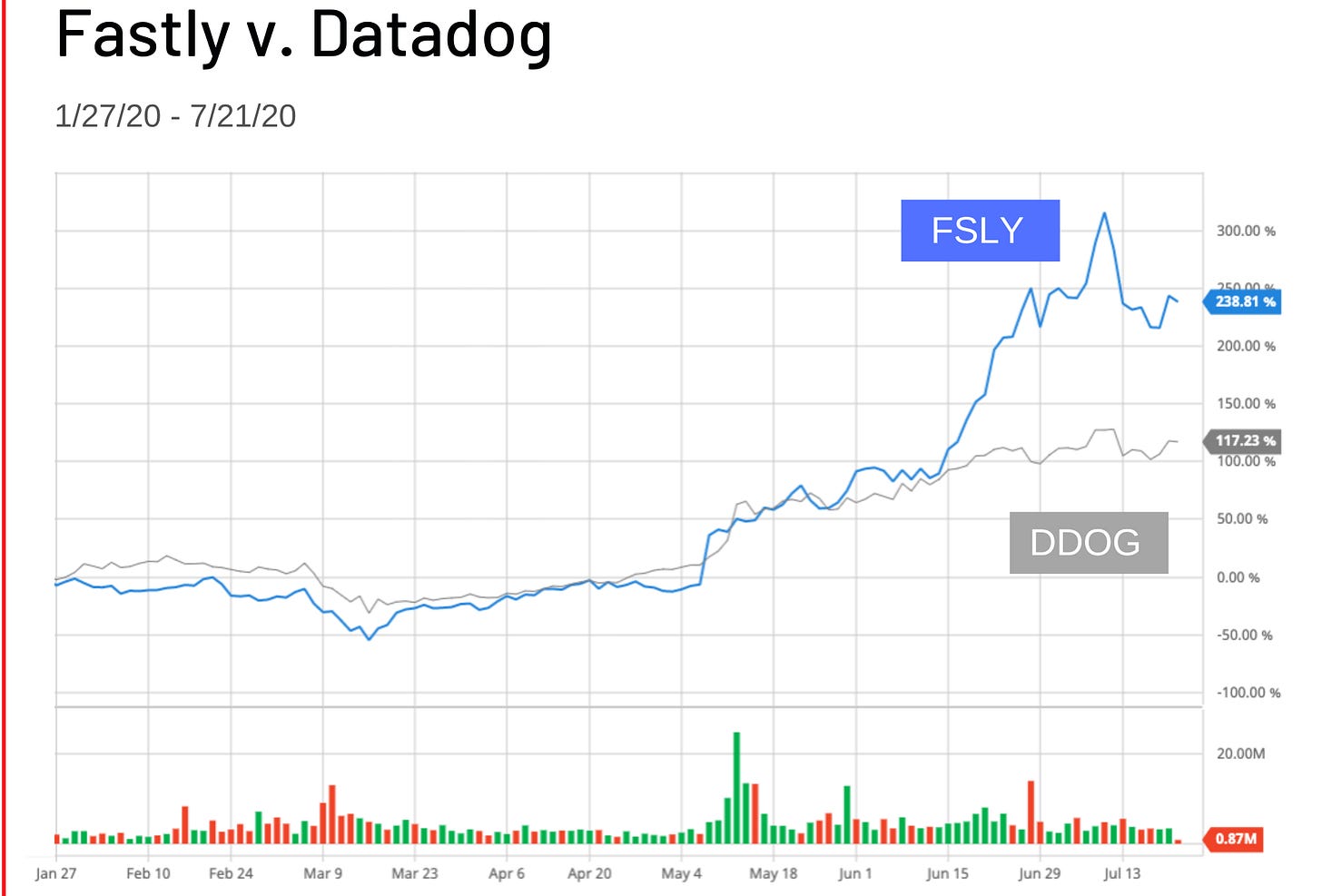

While we believe Rackspace's true peer group centers around consulting shops like Accenture, the company likes to measure itself against businesses like Fastly and Datadog. Those companies' stock prices have been on a tear recently.

Encouragement from FSLY and DDOG | Barchart

Over the past three months, Datadog has more than doubled, up 112%, while Fastly has more than tripled, up 243%. Both companies' stocks have benefited from increased demand for pro-coronavirus plays. Rackspace hopes the market will view it similarly.

A friendly market

IPOs have performed well during coronavirus. There have been 25 non-healthcare IPOs since the beginning of March. On average, the shares of those companies are up 48% since listing. Within that group, technology companies' stock prices are up a mind-melting 90%.

There are a few explanations. Firstly, tech stocks are up broadly — the Nasdaq is up 21% since the beginning of March. Secondly, the WallStreetBets and Robinhood crowd are more excited by novelty and upside than fundamentals. As they see IPOs generate the kind of returns that cause seething envy in their favorite subreddit, they become more interested in buying the next IPO. Lastly, there's some selection bias — like Rackspace, the companies that are benefiting most from coronavirus are coming to market to take advantage of the recent surge in demand.

Rackspace is not the most exciting IPO; it doesn't have the allure of Lemonade, and it isn't going to market via a SPAC, which the WallStreetBets crowd seems to love. But if there was ever a time for Rackspace to IPO, it's now.

Commentary

How to value Rackspace is a puzzle. The company is tech-ish, which means it will find some interest. But its slow growth rate, heavy debts, and lackluster margins make it hard to pin a fair multiple onto. — Alex Wilhelm, TechCrunch

The market feels way different now than in mid-March when everything was falling off of a cliff. Investors are more willing to put their money to work. — Reshmi Basu, Debtwire

The initial public offering of computer hosting services provider Rackspace Hosting Inc. on Friday continued a losing streak for IPOs, dropping 20% on its first day of trading." — Lynn Cowan, WSJ, writing in 2008

Valuation will be key. Early reports suggest the company is dreaming of a market cap of $10bn, which seems high for a sub-tier-one player in the cloud management sphere. — Iain Thomson, The Register

What do you think? Will Apollo see a pay-off on their investment? Do retail investors have a chance to share some of the upside? Or are bigger players about to leave Rackspace in their wake?

We'd love to hear from you. And, if you're down to share our analysis, we'd really appreciate it.