Coatue: An Agile Colossus

The megafund might look like Tiger Global, but it's operating a very different playbook. Coatue’s performance is built around strong in-house research, astute data analysis, and a stellar network.

Actionable insights

If you only have a couple of minutes to spare, here's what investors, operators, and founders should know about Coatue.

Coatue ≠ Tiger. Though they are frequently compared, the two mammoth crossover funds run very different playbooks. Tiger looks to index the private markets and relies on outsourced diligence. Coatue is a more selective picker and leans on its internal research abilities.

Large organizations can still evolve. Though Coatue is one the biggest funds in the world, it has continued to experiment with its structure. Almost a quarter of a century into its lifecycle, the fund shows no signs of curbing its adventurousness.

Data science offers an edge in private markets. In 2014, Coatue began investing in data science capabilities. In the years since, it has built a robust platform called "Mosaic" that surfaces credit card data, customer lists, and company comparisons. Though some question its utility, it is favorably received by founders.

A global outlook can surface new lessons. Coatue was quick to recognize the potential of investing in Chinese tech. It has applied lessons from that geography to Western businesses and visa-versa. Coatue founded a splashy conference to facilitate cross-cultural exchange: "East Meets West."

Hedge fund norms are an uneasy fit with VC. Though it has a fully-fledged private market practice, Coatue's internal culture has been lifted from Wall Street, circa 1985. It is notoriously cutthroat and aggressive. The compensation structure is also non-standard and may partially explain critical departures.

Learn how the best businesses and investors win. Every Sunday, we send a free email that explains the business world’s most important innovations and the stories behind them. It’s high quality business analysis, delivered at no cost to you.

Size usually comes at the expense of agility. The elephant can't match the mouse's darting run; an eighteen-wheeler does not corner like a golf buggy — no tugboat turns on a dime.

Coatue is an unusual colossus. Since Philippe Laffont founded the firm in 1999 with just $15 million, the crossover fund has expanded to a size that puts it among the giants of the financial world. One source I spoke with suggested its assets under management may now reach as high as $90 billion.

Yet, as it has grown, Coatue has seemed to lose none of its nimbleness. On the contrary, increased size appears to have bred greater agility, not less. An organization that began life as a long-short hedge fund has spent much of the last decade spinning up new investing practices. Most notably, that has occurred in the private markets with a now-thriving growth stage strategy alongside carve-outs in fintech, climate tech, and beyond. Not all of its experiments have succeeded—a high-profile internal investment in a new quant strategy flamed out spectacularly. But the fact that a firm of Coatue's scale is willing to move, to experiment, to try, is the core of what makes it special.

Another strange juxtaposition is the firm's clearest vulnerability. While Coatue has charmed entrepreneurs with its fast decision-making, friendly terms, and impressive data science capabilities, it may have done so while neglecting its internal culture. To an unusual extent, sources I spoke with highlighted the firm's high churn, aggressive atmosphere, and corrosive managerial practices. All those who shared their experiences — a group that included former employees, co-investors, and portfolio founders — asked to remain anonymous. In one case, that was explicitly motivated by fear of reprisal. "Coatue can have some vengeance," a former employee said.

Such issues may not matter, at least when it comes to returns. Cultural unrest has not stopped the firm from becoming a global standout. Still, strong talent continues to depart, and while Coatue will believe it can continue to attract gifted employees, humans are peskily non-fungible. Coatue may need to remedy its internal frailties to secure an enduring, positive legacy.

In today's piece, we'll touch on the juxtapositions at the heart of Coatue. In the process, we'll explore:

Philippe Laffont's investing path. Coatue's founder didn't intend to be a stockpicker. His passion for technology transformed into a gift for selecting the sector's best businesses.

Coatue's continuous evolution. What started life as a public market vehicle developed into a true "crossover." Coatue has become a powerful player in venture capital in the last decade.

How the fund makes decisions. Philippe Laffont may be the ultimate decision-maker, but several other power players influence how investments are made at the firm.

What weapons Coatue uses to win. Continued spending on internal data science tooling has paid off. Coatue's platform, dubbed "Mosaic," impresses potential portfolio founders and helps guide decision-making.

The firm's cultural flaws. Coatue has created a high-performance environment but has done so by governing with fear and aggression. That's contributed to high levels of organizational churn, even among senior investors.

Reasons for optimism. The fund's foundation allows it to execute across asset classes and sectors. Given the technical capabilities it boasts, Coatue seems particularly well-placed to further its presence in crypto.

Let's begin.

Origins

Finance has a rich fraternal history. Brothers Lehman, Solomon, Lazard, Harriman, and Brown have all written themselves into Wall Street lore. Though Coatue doesn't bear their name, Philippe and Thomas Laffont represent a continuation of that tradition.

Early days

Born in Belgium, the Frères Laffont spent much of their early years in France. Two years older than Thomas, Philippe described himself as a reclusive youngster, particularly in his teen years. "When I was sixteen, I either did not have the confidence or my parents did not let me go out enough," he noted.

Philippe's obsession with computers and technology filled his free time. That interest proved helpful — he applied to MIT and was accepted in 1985. The following year, Thomas followed his elder brother to the United States, attending the Lycée Français de New York for his final high school years.

Surrounded by technical savants at MIT, Philippe began to feel as if he needed to "repurpose" his talents outside the realm of hard math and science. Though he continued to attain a Master's in Computer Science from the institution, he took a job at McKinsey's Madrid office upon graduation. If he'd had his way, Philippe would have headed West rather than East. Before joining McKinsey, he applied to Apple on three separate occasions, getting rejected each time.

One benefit of moving to Spain was that Philippe got to stay close to Ana Isabel Diez de Rivera, the woman that would become his wife. A lawyer by training, Ana came from an influential family in the country. She was related to Carmen Díez de Rivera, a key figure in Spain's transition from Franco's dictatorship toward a modern parliamentary system.

Learning the market

After two years, Philippe's time at McKinsey came to a close. Though he was ready to return to the US, Ana wanted to remain close to home. They struck a compromise, with Philippe deciding to spend a year working for her family business. It was the kind of job useful in hindsight but frustrating in the moment. Philippe was shunted to a basement office without much to do. To fill his time, he perused the Herald Tribune.

Quickly, Philippe developed a fascination for stock listings. Soon, he was buying the Tribune every day to see how the markets had moved. Not long after, he started investing, picking blue-chip technology companies he felt equipped to analyze. Philippe's early picks included Microsoft, Intel, and Dell. Though based in California, Thomas got in on the action, too, with the brothers sharing ideas.

By Philippe's admission, it was fortuitous timing. In the mid-90s, companies like Microsoft appreciated significantly, giving the Laffonts confidence in their abilities. "We confused luck with skill," Philippe noted, adding that had he started investing during a less bullish era, he "would have for sure given up and done something else."

Tiger Management

Life turns on such moments. After a year in the basement, Philippe and Ana moved to America. Rather than hungering for a job in Silicon Valley, Laffont sought to make it on Wall Street. It wasn't easy. He landed an unpaid role at a mutual fund, but it didn't take long for him to parlay that into a better position. At a conference, he met someone with inroads at Tiger Management, the famed hedge fund of Julian Robertson.

As with Apple, Philippe was rejected at first. Since he had attended MIT, his CV was automatically routed to Tiger's IT department, who promptly responded that they had "no space" but that Laffont had a "wonderful resume."

Thankfully, another door opened. A friend of a friend knew Robertson well enough to get the would-be investor into the room with the "Wizard of Wall Street" — but he only had two minutes. "I went straight to the point," Philippe recalled, telling Robertson that he wanted a job picking technology stocks for Tiger. "I was so direct with what I wanted," he added.

Philippe made a strong enough impression in those 120 seconds for Robertson to introduce him to his technology team. He passed their screening, receiving a role at the storied firm. He would spend the next three-and-a-half years under Robertson's tutelage, learning the trade and focusing on technology and telecom. Not long before Tiger Management closed its doors, Laffont decided it was time to go solo. In 1999, Philippe started Coatue Management.

Coatue Management

Like Robertson, Philippe built his empire from relatively humble beginnings. In 1999, Coatue opened with just $15 million in assets under management (AUM). According to one source I spoke to, Coatue is likely managing between $70 billion and $90 billion today.

Brothers, reunited

Named after Philippe Laffont's favorite Nantucket beach, Coatue was inspired by Robertson. Like his mentor, Philippe planned to buy the best companies and short the worst, though he narrowed his focus to the world of technology. In particular, Laffont focused on "generational consumer technology companies," as one Coatue employee described it. Whereas many peer firms were focused on short-term movements, Philippe wanted to look toward the horizon, searching for businesses that could compound for three years or more. "That's our edge," he said in a rare interview, "Patience and longer-term thinking." (Chase Coleman would launch Tiger Global with a similar premise.)

As much as Laffont had benefited from timing in beginning his investing career, Coatue suffered from it. In December of 1999, when the fund opened its doors, the Nasdaq Composite—an index of the exchange's stocks—stood at 4,000. By March of 2000, it had crested 5,000. Then, the bubble burst.

The dot-com crash saw tech stocks collapse. By late 2002, the Nasdaq Composite lingered a touch above 1,200. Coatue's first three years of investing had coincided with more than a 75% drawdown in the markets. Remarkably, Laffont weathered the storm, showing an ability to manage in adverse circumstances, a skill that attracted further investors.

The following year, in 2003, Thomas would join his brother at Coatue. He had taken a very different path since graduating from the Lycée, attending Yale before heading to California. Thomas worked his way up from the mailroom in CAA's Beverly Hills office. Over his six years at the agency, he worked for Bryan Lourd, an industry heavy-hitter who counts George Clooney, Ryan Gosling, Scarlett Johansson, Paul Thomas Anderson, and Lady Gaga among his clients. Though Thomas became an agent in his own right, the opportunity to join his brother in building a preeminent investment firm was too good to pass up.

One of Coatue's defining hits arrived shortly afterward. Like Scott Shleifer at Tiger Global, Coatue recognized the potential of Chinese technology investments. While Shleifer snagged several of China's "Yahoos," Coatue made the bigger splash. In 2004, the Laffonts bought Tencent at its IPO price. At the time, the markets valued WeChat's owner at less than $1 billion; today, it sits around $590 billion. While Coatue has, of course, changed its position sizing, it nevertheless represented a massive win.

Another critical bet was Apple. As a Coatue employee noted in our discussion, "Philippe probably made more money on Apple than anybody." Though rejected from the company's Cupertino offices, Laffont remained impressed by the business, frequently buying in. Reflecting on his history with Apple, Laffont said, "It just shows how sometimes you do get the things you want but just through a different door."

Better late than never

Though the Laffonts showed a knack for identifying great technology companies, they were slow to recognize a fundamental shift in the industry's financial landscape. In 2000, Tiger Global made its first private investment, backing Russian search engine Yandex. That represented the beginning of an accelerating private market run still in full swing.

Tiger's move into the space was motivated by an understanding that many interesting technology companies had yet to hit the public markets. The firm could accumulate stakes in a business that might not IPO for years by moving earlier. In the process, it built relationships with management teams and developed a sharper understanding of the underlying dynamics. Lessons from the venture practice could be passed to the hedge fund team and visa-versa.

In 2009, DST Global entered the fray with Yuri Milner making his famous investment into Facebook. As one former Coatue investor active during this era noted, "The narrative at the time was that [Tiger and DST] were stupid."

Perhaps that's part of the reason that it took Coatue time to catch up. In 2013, the firm made its move, opening up an office on Sand Hill Road in the same building as Andreessen Horowitz and beginning to scout for private market deals. The new initiative was led by Thomas Laffont and Daniel Senft, a talented stock picker and long-time lieutenant.

Without a strong brand in Silicon Valley, Coatue found unusual ways to break into the ecosystem. Even before they'd raised a dedicated venture vehicle, the team secured Coatue's first private investment, purchasing secondary shares in cloud management system Box. As a former employee noted, that opportunity had arisen thanks to the firm's Wall Street connections, with a Morgan Stanley banker flagging the upcoming sale.

It was a start—one propelled forward by the closing of a formal venture vehicle. Pitchbook data suggests Coatue's first private market fund totaled $185 million, though the employee I spoke with remembered it as $350 million. (They might have been thinking of a $355 million growth fund raised in 2015). Whatever the figure, Thomas Laffont and Daniel Senft had money to spend. The Box deal was followed up with direct investments into Hotel Tonight, Evernote, and Lending Club. The following year, Lending Club would IPO, marking Coatue's first venture liquidity event. It didn't take long for Coatue to set its sights higher.

Bigger fish

A former investor with knowledge of this era mentioned that Coatue identified a few high-priority companies to target. "Uber was our white whale," they noted, lamenting that "Travis wouldn't give us the time of day."

Other marks included WhatsApp and Snap, with Coatue's interest in the companies influenced by their work on Tencent. They had seen the power social media and messaging businesses had to translate attention into monetization. Jan Koum and Evan Spiegel's companies were considered best positioned in Western markets. While DST would go on to snag a sweetheart deal on the messaging service, investing even after Facebook had agreed on an acquisition, Coatue got its chance with Snap.

Per the former employee, getting into the deal was a five-month endeavor. First, Coatue tried to win Snap's Series B but was beaten out by Insight Venture Partners. The source recalled that it was the type of deal in which terms escalated rapidly, with a $200 million valuation skyrocketing to $800 million in a matter of days.

Coatue was intent on not missing out again. To win Spiegel over, Thomas began a "masterful" full-court press, wooing Snap's founder with expensive dinners and introducing him to celebrity contacts through his network at CAA. The Coatue team also demonstrated the rigor with which they had studied the social media space, particularly the Chinese market. That was compelling to Spiegel, who made frequent trips to China to understand the local dynamics better.

It paid off. In December of 2013, Coatue secured the chance to invest $50 million into Snap at a multibillion-dollar valuation. As the ex-Coatue investor recalled, "That was what put us on the map."

Hitting its stride

While Coatue didn't have name recognition in tech circles, it had other weapons: the firepower of a hedge fund. As demonstrated by the Snap deal, early-stage companies valued deep research and proprietary insights. With a much larger staff and more powerful instrumentation than a traditional venture firm, Coatue shone in this area. Though the private market team didn't gain access to Uber, they won over Logan Green and Lyft with their research.

Before meeting management, Coatue's team took trips with Lyft drivers, taking pictures along the way. Those photos were included in a pitch filled with insights on the space. As a source said, "it was a marketing deck."

That soon became something of a calling card for Coatue. Rather than heading to a meeting and waiting to be pitched, the firm's investors would do the pitching. With the help of the hedge fund team, they'd compile research and walk through their thoughts on the market. As the source mentioned, it demonstrated to startup founders that Coatue was intelligent, thoughtful, and willing to do the work. Today, this is common practice for later-stage firms, but it was unusual at the time. It yielded promising results, with a former investor remarking that "it worked ninety-plus percent of the time."

To bolster its capabilities, the Laffont's staffed an in-house research team, managed by a former BCG consultant. It's interesting to compare this integrated approach with Tiger's outsourced model. Whereas Coleman's firm relies on Bain and other consultancies to get up to speed on a business, Coatue established this practice themselves.

Around this time, Coatue also began heavily investing in a data science practice. In 2014, a young Wharton student, Alexander Izydorczyk, interned at the firm. Izydorczyk worked closely with Philippe Laffont to develop Coatue's capabilities in this area, eventually joining full-time. By 2017, this initiative began to pay off, with Coatue providing tailored insights to prospective investments and portfolio companies.

In tandem with this data drive, Coatue widened its aperture, pursuing deals in sectors it had previously eschewed. The fact that the firm felt confident in doing so showed it had begun to hit its stride. Coatue's public investments in China had given them an understanding of the geography that they parlayed into the private markets. To lead those efforts, the fund brought in Tony Zhang from DCM Ventures, a firm with deep connections to China and outstanding performance. Indeed, DCM's 2014 vintage is one of venture capital's best-performing funds, with a 2021 piece reporting 30x returns.

Zhang made his presence felt, brokering investments into Didi, Uxin, ofo, Meituan, and Kuaikan Manhua. A former investor suggested that Coatue invested about half of its first two funds in China. Ride-hailing business Didi was considered a "very important investment." Of the group mentioned above, three are now publicly traded—ofo and Kuaikan are yet to reach that stage.

Coatue formalized its transnational approach with the introduction of the "East Meets West" conference. Thomas Laffont's brainchild brought together luminaries from Asian and Western tech ecosystems alongside a liberal sprinkle of celebrities. Kicking off in 2015, "East Meets West" was initially held at the Four Seasons on Hawaii's big island before moving to California's Pebble Beach in later years. One source described it as "a pretty brilliant move," with Coatue getting credit for bringing notables like Mary Meeker, Yuri Milner, and Pony Ma into conversation.

Of course, there have been awkward moments. One attendee recalled a panel event featuring former Secretary of the Treasury Larry Summers and Coinbase CEO Brian Armstrong. Unconvinced by the cryptocurrency sector, Summers made his opinion known, pressing Armstrong in the process. "It was a little embarrassing," the watcher noted.

The fact that Coatue could even preside over such a moment was a testament in and of itself. The firm had established a name and network in both American and Asian venture markets in just a few years. But it wasn't time to sit still.

Moving earlier

Coatue's grip on growth investments grew firmer, so it started to look upstream. Coatue realized, alongside many other investors, that seeding a company fundamentally changed the dynamic with a founding team. The shared history and demonstrated trust fostered a tighter connection that could prove vital in securing much larger allocations down the line. While Coatue had shown an ability to win competitive late-stage rounds thus far, the market had grown more crowded. To stay competitive, Coatue needed to move earlier.

The firm brought in two established names to kick off the effort: Matt Mazzeo and Yan-David Erlich. Mazzeo had famously worked at Lowercase Capital, a firm with legendary returns. He also shared Thomas Laffont's connections to Hollywood, having spent more than seven years in business development at CAA. Erlich brought high-level operating experience to the table alongside an investing track record, having founded connected worker platform Parsable, incubator MuckerLab, and firm Outlier Ventures.

Coatue soon brought a heavy-hitter aboard to manage this team: Dan Rose. The former VP of Partnerships at Facebook, Rose was a long-time golf buddy of Thomas's and had stayed close to the team for years. He soon brought along a former colleague, Caryn Marooney, who had served as Facebook's VP of Communications. Rose took on the role of Chairman while Marooney joined Mazzeo and Erlich as General Partners.

Around this time, Coatue bolstered its late-stage team, too. A co-investor with ties to the firm pointed to the arrival of Kris Fredrickson as something of a turning point, with the former Benchmark principal refining the team's tastes. Sebastian Duesterhoeft and Lucas Swisher arrived from Silver Lake and Kleiner Perkins, respectively. The inference from this source was that such additions represented a step up, albeit one secured at a high cost. "They found a cohort of people and paid them a shitton of money," they explained. It seemed to give the firm the firepower to keep expanding its efforts.

Expanding the aperture

In many respects, the entire story of Coatue can be seen as a continuous mandate expansion. What started as a hedge fund focused on public consumer technologies has gradually grown to include growth and early-stage funds. New sectors have accompanied this structural growth. Since 2013, the venture team has moved beyond consumer internet and into fintech, enterprise software, healthcare, and crypto. All have become legitimate hunting grounds for the once narrow fund.

This adventurousness is perhaps the defining characteristic of Coatue's last five years. Increasingly, the firm is a true generalist in the private markets, a flexibility that has resulted in a much tighter deployment schedule. Coatue made 58 investments in 2020, a figure that jumped to 165 in 2021. Quarter four of last year was the firm's busiest ever, with 55 deals announced during that period alone. That's still a way short of Tiger's 362 for the year but is an undoubtedly rapid pace.

It seems to have worked, for the most part. While one co-investor remarked that Coatue had been left "holding the bag" on a few deals, it has also secured stakes in some of the most consequential businesses of the last few years. Even though they may have been late to the sector, the firm has established an impressive base in crypto with investments in Fireblocks, OpenSea, Alchemy, Dapper Labs, and Dune. Those have contributed to the growth team's purportedly strong performance, with a 2021 report suggesting that Coatue's 2017 vintage boasted an internal rate of return (IRR) of 47%.

According to one source, Coatue's early-stage group has yet to find equivalent success. Referring to a $500 million vehicle, the former investor said, "As far as I know, the returns on that fund have been pretty bad." A venture capitalist from a different firm echoed that statement, saying, "On the early side, it's not there."

It is still relatively early days. Less than a decade into its private market sojourn, Coatue has grown its footprint, developed new competencies, and found ways to win. For an organization of Coatue's size, such dexterity is both unusual and worthy of recognition.

Every Sunday, we unpack the trends, businesses, and leaders shaping the future.

Operations and structure

Our work thus far has given a sense of how Coatue developed. It is now time to study the firm's different pieces, examining how they fit together.

Fund structure

It's worth taking a moment to outline Coatue's business components explicitly. Fundamentally, there are three core business lines: public market investing, growth investing, and early-stage investing.

Coatue has also experimented beyond these primary categories. A source close to the firm pointed out the existence of four additional Special Purpose Vehicles (SPVs). One is focused on fintech, another on climate tech, and a third on the Chinese ecosystem. Coatue invests in both private and public companies from these three SPVs. Climate tech seems to be a particular focus, with a new $2 billion SPV recently added. Coatue has already taken significant positions in Tesla and Rivian.

The fourth vehicle, named the "Opportunity Fund" is exclusively geared to the public markets and was raised during the brief stock market collapse in March of 2020. My source noted that Philippe Laffont realized the breakout potential of businesses like Zoom and Wayfair, raising $1 billion to snag them at depressed valuations. It reportedly generated more than 100% return within a year.

Though no longer operational, Coatue did once have a fourth "core" investment practice, trying out a quant approach. Data lead Alex Izydorczyk helmed this $350 million fund but struggled to generate consistent returns. After a strong 2018, Izydorczyk's division made 2% in 2019 and toiled in 2020. Coatue returned the fund's capital by the middle of that year and slashed the team. Reports suggested that Izydorczyk was a harsh leader with brutal expectations. He left the firm in 2021. As we'll discuss later, Izydorczyk's approach appears to be representative of a firm with a frequently corrosive culture.

One interesting side effect of Coatue's different standalone funds is that each vehicle has a standalone "scorecard." Limited partners (LPs) can see which strategies are paying off and make decisions accordingly. While that might provide more granular information, it also opens the firm up for criticism. For example, earlier in this piece, we shared that some sources suggested Coatue's venture strategy had mixed results. Would this even show up if Coatue blended investments? One former investor compared Coatue's preference for atomizing its vehicles with Tiger's more unified strategy, remarking, "Tiger's approach is smarter."

Hierarchy and decision-making

Coatue's chain of command is both simple and convoluted. I was fortunate to get a relatively clear picture of the firm's internal hierarchy through my discussions.

Founder Philippe Laffont sits at the top and is the firm's ultimate decision-maker and portfolio manager. Thomas Laffont and Daniel Senft serve as trusted lieutenants with greater latitude than other senior investors. Once you move below this level, things quickly get complicated. While investors might focus on particular stages more than others, there is considerable fluidity with hedge fund analysts contributing to early-stage venture deals and visa-versa. Some leaders manage sectoral areas while others govern a particular asset class practice.

For example, Michael Gilroy and Rahul Kishore were identified as key leaders of the firm's fintech practice—a sectoral focus—while Dan Rose was pointed out as the manager of the venture asset class. Perhaps the best way to understand Coatue's hierarchy, then, is through a matrixed approach. Based on my conversations and research, that representation might look like the chart below. Leadership is represented along the various axes, with key individuals shown in relevant cells:

Of course, this is far from complete. The firm has too many employees to represent here. Nevertheless, it gives a sense of how Coatue functions and governs.

In terms of decision-making, sources indicated that Thomas Laffont and Daniel Senft could make investment decisions within reason. "No one's begrudging ten or fifteen million checks," an investor stated, suggesting that larger tickets likely needed Philippe Laffont's approval. Investors further down the pecking order may have to adhere to a similar process. Ultimately, the buck stops with the man who started the firm: Philippe Laffont.

Playbook

Our work thus far has given a sense of Coatue's development and internal structure. It is now time to examine the firm's current playbook. We'll specifically focus on Coatue's private market work, walking through how the firm sources, evaluates, wins, and supports deals. In doing so, we'll have a chance to juxtapose Coatue's approach to Tiger's, the investor to which it is most frequently compared. In doing so, we'll learn that the superficially similar firms are leveraging meaningfully different tactics.

Sourcing

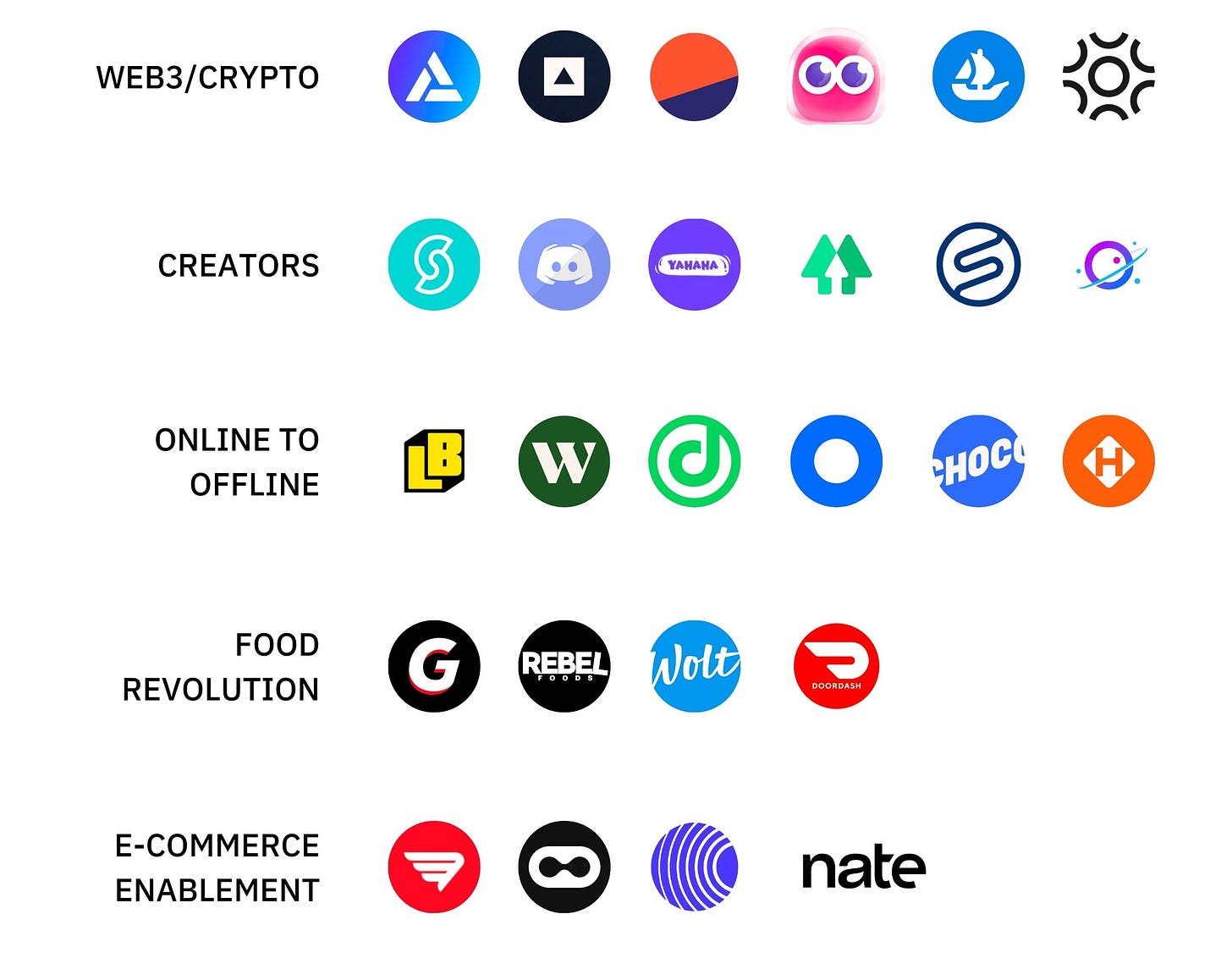

Unlike Tiger, Coatue does not seem to want to index the private tech sector. Though the Laffonts' firm deploys aggressively, it does seem to be pickier. Though there's room for deviation, Coatue tends to be thesis-driven, looking for investments that fit one or more "macro trends."

A source with knowledge of the firm highlighted a few examples:

The emergence of new business models through web3.

The rise of the creator economy.

The introduction of historically offline businesses to online tooling.

The revolution in food delivery.

The enablement of e-commerce.

Looking at Coatue's investments over the past few years, we see how the portfolio maps to these megatrends.

Of course, several of these startups could fit in multiple categories. Regardless, more than many other funds, Coatue knows what it's looking for.

Evaluating

For the most part, Coatue evaluates companies in-house. While one founder I spoke with mentioned the firm's use of outside consultancies, these seem to be used more in a supporting role. Famously, Tiger outsources much of its evaluation and research to Bain, freeing up its investing time to focus on securing allocation.

Though Coatue looks for many of the same characteristics as other VCs, a source described it as a particularly TAM-focused investor. In and of itself, this doesn't sound like much, but the granularity with which Coatue seeks to validate a total addressable market (TAM) stands out. A co-investor with the firm separately noted this, explaining that while a traditional VC might look at the high-level figure for a specific industry, Coatue digs into the details. For example, when analyzing a business like Datadog, the firm doesn't just look at the market for cloud monitoring software; it carefully analyzes attachment rates for similar products and examines how departmental budgets are typically deployed. "It's very different than others," the co-investor remarked, noting that if Coatue's team doesn't think a TAM is large enough, they will pass. Again, this might sound logical but runs counter to other firms' strategies; I've heard more than one respected VC mention that their biggest mistakes have come from over-indexing on market size.

Though Coatue's data abilities may play a more prominent role in winning a deal, it also helps with analysis. One source shared an anecdote of how the firm's system, named "Mosaic," drives good decision-making. You might have heard of a company called Headspin. In early 2020, the mobile testing platform was seen as a breakout business based on data the company had shared with the public. Headspin raised $60 million on the back of that traction, receiving a valuation of $1.16 billion. Seventeen months later, the SEC and DOJ charged the company's co-founder with fraud, alleging he had misled investors. In part, Coatue passed on investing in HeadSpin because Mosaic suggested much weaker figures. "We didn't see the usage data," an investor was believed to have said.

Finally, when evaluating a deal at the later stages, Coatue's internal target is a 3x return or above. Anecdotally, this is below the hurdle traditional growth firms set, but maybe more in line with other crossover funds.

Winning

Coatue has a few weapons when it comes time to win over a founder. The four most important are as follows:

Unique data insights via Mosaic

Influential connections

Surprising hustle

Flexible pricing

Its most differentiated advantage is Mosaic. What exactly is this product?

Mosaic is a fully-featured, intuitive data analysis dashboard. It started by aggregating and parsing credit card data, showing what purchases had been made where. This could be extremely useful. For example, Coatue could show Lyft CEO Logan Green how his company stacked up against Uber on a zip code by zip code basis.

It could do the same thing for DoorDash's Tony Xu, outlining where the food delivery business was gaining and losing share, which restaurants were driving most online sales, and which competitor he might be interested in acquiring.

Though initially impressive, Coatue's advantage was eroded by the launch and expansion of Second Measure. The startup offered similar credit card data at a price point many businesses could afford. To the firm's credit, it kept investing in the project, plowing more than $30 million a year into data science initiatives. In time, Mosaic took on new functionality. By purchasing alternative data sets, including expense account data, Coatue could piece together customer lists, a feature that was particularly useful for enterprise businesses.

For example, Mosaic might parse expense data from a company like Salesforce. In doing so, it might note that a certain number of users paid for Adobe XD. This insight is extremely relevant for competitive startups like InVision or Figma. With a large enough data set, Mosaic could effectively create a list of prospects for a given startup, prioritized by the amount each was spending on a competitive product.

The final core piece of Mosaic is its benchmarking capabilities. Coatue creates financial models for the businesses it analyzes. These are uploaded to Mosaic, enabling the company to compare new investments to historical data. It can look at a SaaS platform with $20 million in annual recurring revenue, for example, and see what top decile net retention looks like. Similarly, Coatue can study a new marketplace and judge where average moderation spending sits. Perhaps only a handful of firms have institutionalized their experience quite so effectively.

What does all of this amount to? Across the sources I spoke with, Mosaic seems to be impressive but not that important. It works cleanly and suggests electrifying power. But do founders really use it?

"Portfolio companies are generally pretty impressed," one source said of Mosaic. Another expressed a similar sentiment, adding, "I honestly think [it's] still more marketing fluff than game-changing."

The same tension exists when it comes to connections. Philippe Laffont has been extraordinarily rich for a long time. Mere existence at that altitude tends to come with influence and sway. If he chooses, he can very likely make close to any introduction for a portfolio company. Thomas Laffont is likely able to manifest a similar network, gilded with celebrity connections.

Of course, "East Meets West" is the clearest instantiation of Coatue's clout. Though the last two years have halted festivities, one source noted that they expected its return in one form or another. Rather than focusing exclusively on sharing learnings between Asia and the United States, it is likely to reflect the firm's global focus. Recent iterations have centered on bringing leading executives together from around the world.

How valuable is the event? Again, there seems to be a blurred line between a tangible return and alluring triviality. "It's great for all the portfolio companies," one source said, highlighting it as a core point of differentiation. Another remarked, "It's way more schmoozy than it is business value."

Coatue's hustle doesn't seem to be up for debate. This is a firm that moves quickly and jumps on opportunities. That can make an extremely favorable impression on entrepreneurs. One portfolio founder I spoke to recalled how they were introduced to Coatue at the end of a fundraising process. Despite having the clock against them, the firm arrived at the first call having prepared and researched the business. "I immediately loved them," the founder noted.

When Coatue was informed during a second call that the founder expected a term sheet from another firm that day, the partnership and back-office team sprang into action, sending an offer of their own by the end of the one-hour meeting. Afterward, senior management texted directly to express their excitement and get the deal across the line.

Another portfolio founder shared a similar experience. This time, Coatue moved first. Though the company wasn't actively raising, Coatue pre-empted fundraising discussions arriving with thorough research and data, used in a "very, very impressive way." With almost no effort required on the founder's part, a round was concluded in a couple of days with less than two hours of calls. In the process, Coatue doubled the valuation of a competing term sheet the founder considered notable.

These are remarkable anecdotes and showcase Coatue's operational firepower as well as the drive of its team. A co-investor recalled how surprised they were to learn that Thomas Laffont had hopped onto a call with a seed-stage CEO in the midst of a heated fundraise. "It shows the urge to win...and the lengths he'll go to," the source said. "They hustle hard."

As alluded to, Coatue's final weapon is price. As noted, the firm does seem to underwrite to a different multiple than other growth firms, giving them the latitude to offer favorable terms. That's not to say that Coatue is valuation insensitive. On the contrary, the team will walk away from deals it believes cannot offer a sufficient return. One person I spoke with pointed to Patreon as an example. Though excited by the creator economy and interested in the business, Coatue apparently couldn't find a viable way to make the numbers "stack up." Speaking of the firm's stance, they said, "We're going to be disciplined about price."

Supporting

Coatue's involvement doesn't end once an investment has been made. While Tiger Global is hands-off by design, Laffont's firm looks to balance proactive support with latitude. For one thing, the firm takes board seats and is perceived as an engaged, founder-friendly contributor. The portfolio founders I spoke with said that Coatue strikes a good balance, succeeding in being helpful without sliding into meddlesomeness. "They fly at the exact perfect level," one reported.

Beyond participating in governance, Coatue leverages its data capabilities to support its investments. Portfolio companies receive customized versions of Mosaic, fitted with relevant information. "It's bespoke to each company," one source said.

The Laffonts' connections can also prove consequential at this stage. A source pointed to the firm's work with CommonStock, a social network for investors, as an example. After leading the Series A, Philippe Laffont reportedly sent a WhatsApp message to a group chat featuring dozens of billionaire investors, introducing them to the service. That network is one that few people in the world can access with such ease.

Though in its early stages, Coatue has built out additional portfolio services, including recruiting support. In speaking of the firm's platform expansion here, a source compared it to Amazon's knack for transforming cost centers into revenue generators. While Coatue's services might not bring in revenue directly, they can help portfolio businesses operate more smoothly and perhaps win deals on the margin.

For these reasons, a co-investor summed up Coatue as "a better offering than Tiger, in my mind...you get more out of it." Meanwhile, a former employee said of portfolio support:

Sometimes it landed perfectly. Sometimes it really, really sucks... I'd be surprised if 80% of the founders in the Coatue portfolio would point to Coatue as their most helpful investor.

Though hit-and-miss, Coatue seems to be doing the essential part well: leaving its portfolio founders feeling supported but not smothered.

Learn the playbooks of tech's most consequential companies.

Culture

In researching Coatue, one issue appeared too many times to ignore: its aggressive internal culture. While many good things were said about Coatue's team and leadership— we will discuss these, too—there appear to be persistent managerial issues that start at the top.

Leadership

The three individuals at the top of the firm are Philippe Laffont, Thomas Laffont, and Daniel Senft. Each one's character is, in some respect, reflected in the organization they have built.

That is most true of Coatue's founder, Philippe Laffont. As his educational background suggests, Philippe has a natural gift for numbers. He can analyze and recall large data sets with eerie skill. One source said, "He remembers every number that you give him, even if you gave it to him five years ago."

That's more than just a nifty party trick. Rather, it allows Philippe to assess the fundamentals of a business quickly. Another person I spoke with described how the fund manager can jump into a spreadsheet blind and immediately suss out an issue, saying, "If there's an error in row 363 of your model, he'll find it."

Phillippe has the gift of translating that granularity into big bets. "What he does really well is super size the best ideas throughout his career," an investor close to the firm said, citing Coatue's track record of doubling down on breakout hits like Apple, Tencent, and Bytedance. Equally, Philippe knows when to pull back, running a more cautious strategy during some of 2021's most volatile months. "He's a very good poker player in the market," the individual noted.

These gifts come with a particular fervor. "Philippe is very intense," one person said. That is a positive trait when applied to the markets but seems unproductive on the home front. An exposé described him as a "screamer," a portrait corroborated in my conversations. One firm rumor is that Philippe threw a stapler at a subordinate in a pique of rage. While the source that relayed this story noted that they weren't certain whether it was true, that it seemed plausible to them is an indication that the elder Laffont brother is not always in control of his emotions.

He also seems somewhat inscrutable, with a venture capitalist describing him as "an odd duck." One source recalled a conversation around the time Coatue began investing in the private markets. Philippe relayed that one of his primary motivations for getting into venture capital was to secure personal tax advantages. While that might have been true, it suggests a narrowly pragmatic worldview.

While he may lack some of his brother's public market acuity, Thomas Laffont is reportedly the more affable of the duo, described by one person as "very charismatic." Perhaps because of that, he's succeeded in building an impressive network that's come in handy when wooing companies like Snap and Spotify. He tends to be a big picture thinker with a skill for playing devil's advocate, poking holes in consensus opinions.

Though Thomas may have a higher EQ than Philippe, he seems to share his brother's intensity and temper. A source described both Laffonts as "very scary." They further discussed Thomas's fickleness, describing his opinions as moving with the market.

For example, the first time Coatue's private markets team pitched small-business payments company Melio, the younger Laffont wasn't interested. "Thomas kind of shat all over it," a source with knowledge of the event said. However, as public market competitor Bill.com grew its value, he reversed his decision, making a significant investment in Melio. Suddenly, the source remembers, we wanted "everything" involving payment processing and back-office support.

Another time, a source remembered pitching a SaaS business on a day where companies in the sector had taken a beating. They knew they had "no chance" of getting Thomas to agree to a deal.

Though he may cast a smaller shadow, Daniel Senft is a vital player at the firm. Indeed, he may be Coatue's best stock picker. Senft primarily focuses on consumer internet businesses and has scored some major wins in that category, with the fund's backing of Bytedance, Tencent, and Facebook apparently down to him. One source suggested Senft had likely been responsible for Coatue's largest "aggregate winners."

After spending more than thirteen years at the firm, Senft also seems to have developed a talent for communicating with Philippe. With the fund manager's time limited, most pitches need to be given in a minute or so. A source said that Senft masters this compression, efficiently articulating nuanced topics.

Outside this trio, Coatue has several other key figures. Though commentary on this group was much more limited, the firm's private market team seems to be primarily well-received, especially by external parties.

One portfolio founder singled out Matt Mazzeo for particular praise, noting his positive contributions to the business. "He has an incredible product mindset," the founder said, noting that they considered Mazzeo one of the best in the world in this area. The same individual pointed to David Schneider, formerly of ServiceNow, as another stellar addition. To this founder, Schneider exemplified the ethos of the firm:

You can be ambitious and aggressive and, at the same time, be a good human. That's kind of the common thread among everyone at Coatue.

Caryn Marooney was also name-checked, with a source noting how valuable she had proven to be for portfolio company Notion. Marooney's experience as VP of Communications at Facebook has been vital in helping the company stand out in the crowded category of note-taking and information management.

Aggressive management

As demonstrated above, there are leaders at Coatue that have earned favorable reputations. By and large, however, the firm seems to have allowed an aggressive, intensive culture to flourish.

Perhaps this is by design. Philippe Laffont came up during a different era and may have experienced a brasher managerial style. In a previous interview, he spoke almost gleefully about the "testosterone" of life on Wall Street, and he is certainly someone that has thrived in competition. Coatue's manager may consider a high-octane environment essential to achieving high performance. "Philippe thinks the cream rises to the top," one person told me.

Coatue's intensity is understandable from this vantage. Nothing significant is built without sweat, and the best teams tend to be extraordinarily hard working. However, other organizations have shown it is possible to achieve remarkable outcomes without the coarseness of Coatue's methods.

One former employee remembered their time at the firm, saying, "I've never been yelled at more...Frequently, we would get called a fucking embarrassment." Thomas Laffont called up underlings via Zoom before administering his critique, a habit that has left a lingering mark. "Every time I hear that ringtone, my heart starts to race," the source noted.

This individual's experience was not isolated. Others described it as "cutthroat," and a "burn and churn" atmosphere. "Two and out, two and out, two and out," a different source remarked, describing Coatue's habit of chewing up employees and spitting them out every two years.

Not only does Coatue lose many talented investors thanks to its approach, but it also seems to offer little development for those it retains. "There's no, like, mentorship programs at Coatue," a source said. This feels like a particular disappointment given Philippe Laffont's history with Tiger Management, a firm fabled for its cultivation of young talent. Indeed, even compared to contemporary hedge funds and fellow crossovers, Coatue's casual venom seems out of touch.

Ultimately, Coatue may not care about its cultural issues as long as performance remains solid. For many, the opportunity to invest in exceptional businesses is worth the pain. The person that remembered Thomas Laffont's Zoom calls with a shiver ended our conversation by saying, "I still come out net positive...I would still tell founders to take money from them."

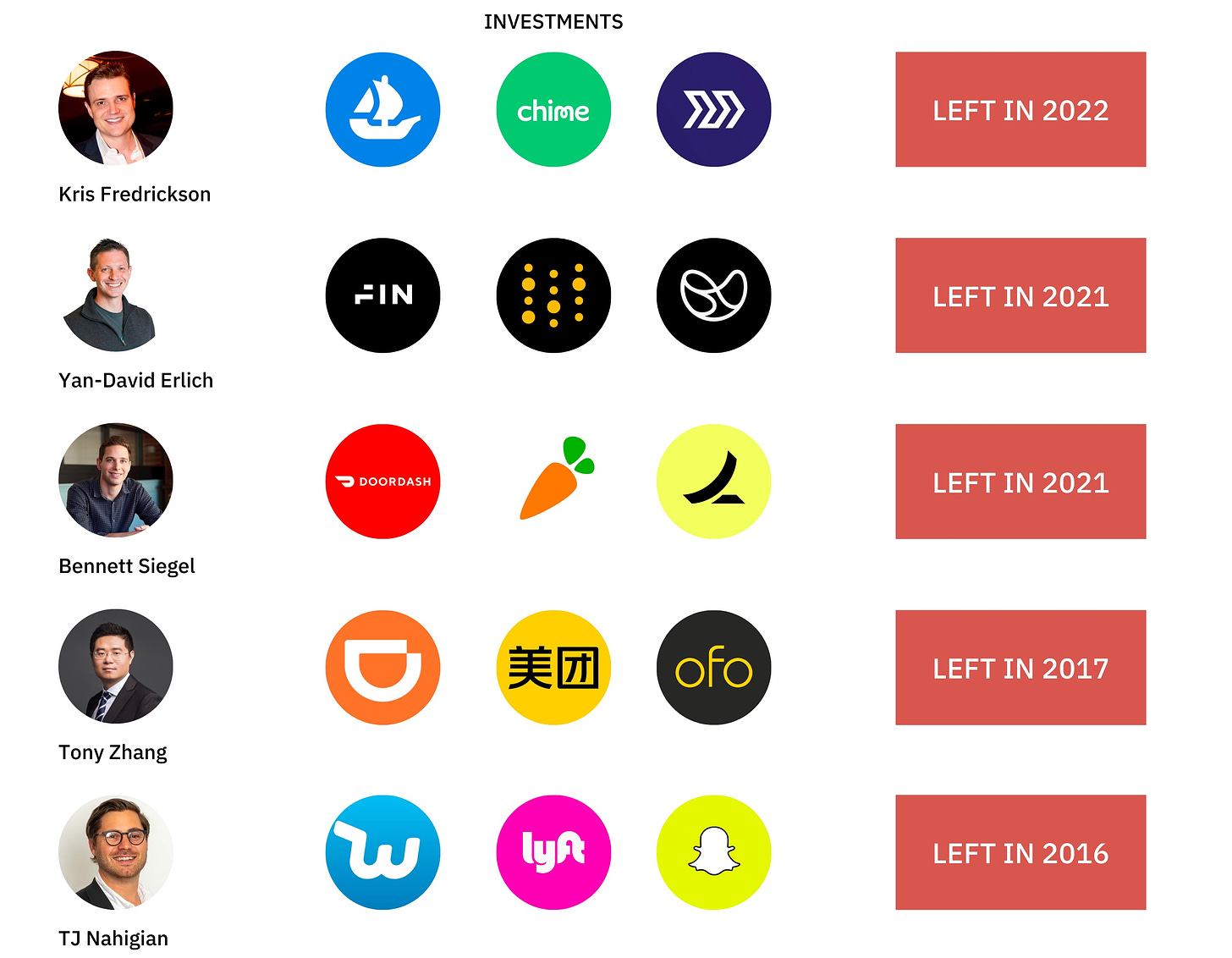

Compensation structure

Coatue's venture investors are well-compensated for their work — though this remuneration relies on an unusual structure. Typically, venture capital firms reward investors with "carry," the share of profits realized by a general partnership. Traditionally, the GP's carry totals 20%, part of which may be given to junior investors, too. The premise behind this model is that it aligns incentives, meaning that investors are handsomely rewarded when their bets pay off.

Coatue adheres to much more of a hedge fund model, even with its private market arm. According to one source, even GPs don't receive carry on the investments they make, getting compensated in cash and bonuses instead. The same is true of junior investors, with most receiving low six-figure base salaries. Multi-million dollar bonuses are discretionary and not explicitly linked to an individual's investment performance. While high salaries mean that "no one's crying," this approach does remove the fundamental alignment mentioned earlier. Though GPs and other investors can undoubtedly become very wealthy by working at Coatue, becoming outlandishly rich typically requires ownership of a high-performing asset. Tears might not be spilled over such things, but there are only so many times you are willing to endure investing in the next Notion, OpenSea, Lyft, or Meituan without securing the bag. This structure might partially explain some of Coatue's losses over the years:

Of course, no individual is solely responsible for a single investment. Other investors will have played vital roles in each one of these businesses. This is perhaps the point—a game that is played as a team should share the spoils of victory.

Again, this is a core difference from Tiger. One of the sharpest moves Chase Coleman has made is sharing the upside with the broader partnership. Doing so allowed several colleagues to reach billionaire status, keeping them from spinning out. As discussed, Coatue already struggles with retention; spreading the wealth might help.

Experimental DNA

Though there are elements of Coatue's culture in need of improvement, one aspect is almost entirely admirable: the firm's willingness to experiment. In that respect, Laffont's construction resembles the companies in which it invests more than many of its rivals. While its asset management peers tend toward the fusty and uninspired, Coatue has innovated. "The thing that Coatue does not get enough credit for is that when they experiment, they experiment hard," one former employee remarked.

It's interesting to envision how this DNA might manifest over the next couple of years. While one individual suggested Coatue would become more like Tiger, taking an index-based approach, that seems to run counter to the way the firm likes to work with its businesses. Instead, we might see it create something equivalent to a suite of thematic-ETFs, spanning private and public markets. Already, we've seen the firm spin up SPVs for focus areas like fintech and climate. Why wouldn't it do the same for crypto, healthcare, and enterprise software?

Crypto feels like a huge opportunity, one well-suited to the firm. Not only has Coatue established itself in the ecosystem thanks to a string of successful bets, but it should be able to leverage Mosaic to great effect. The crypto space has vast publicly available data but few products surfacing valuable insights. Additionally, though the markets are very different, having experience trading public assets is likely helpful when managing tokens.

It's a shame that Coatue has let the man involved in many of its best crypto investments leave: Kris Frederickson. He was preceded by Matthew Mizbani, also active on the crypto team, who departed to become a Partner at Paradigm.

Coatue may need to staff up and give talent the environment and compensation to succeed to execute on this approach. Despite the firm's flaws, it has done a stellar job reinventing and renovating itself to accommodate new dynamics. Few would bet against them doing so again.

"Largeness" and "greatness" sound like synonyms, but each captures some meaning the other misses. Understanding Coatue sometimes feels like an attempt to differentiate between those two words. Coatue is large—but is it great?

In almost all respects, the answer is yes. No other firm has constructed quite such a sophisticated constellation of attributes. An exceptional hedge fund has sprouted a growth investing practice, which in turn, has hatched an early-stage group. SPVs have sprung up to meet fresher needs, fortifying and adding to the structure. Robust data science capabilities unite these components, allowing them to work and think together. Observed as a whole, it is a lovely piece of financial architecture, displaying the intention of a master craftsman and instinct of an artist. It is great—with each deal won, a testament to the fact.

Only when observing Coatue's culture does this illustriousness look blemished. Though the firm has done much worthy of admiration, the manner in which it governs its team makes it feel rather less remarkable. Suddenly, greatness is lost, though largeness remains.

Coatue is not too big to change, though. Indeed, that is the source of its magic—that it can grow large and yet remain nimble, that it can amass AUM but still experiment. It should direct its next such experiment inward.

The Generalist’s work is provided for informational purposes only and should not be construed as legal, business, investment, or tax advice. You should always do your own research and consult advisors on these subjects. Our work may feature entities in which Generalist Capital, LLC or the author has invested.