Roblox: Cultural Currency

After a two month delay, social gaming platform Roblox is headed to the public markets. It could be a blockbuster.

Roblox in 1 minute

After a two month delay, social gaming platform Roblox is headed to the public markets. It looks like time well-spent with the company using the interlude to raising $520 million in private capital. That new funding valued the business at $29.5 billion, a far cry from the $8 billion to 10 billion at which Roblox was expected to price its offering.

That enthusiasm may be well-founded. Roblox grew revenue 58% year-over-year, logging $588.7 million in their original filing. Bookings expanded a staggering 171% over the same period. Perhaps more important are the company's bright prospects in China and the unique cultural apparatus that powers the platform.

Analysts

Introduction

Scott Fahlman knew what was needed: a joke marker.

A computer science researcher at Carnegie Mellon in the 1980s, Fahlman was, like many others, active on the school's virtual bulletins, often referred to as "boards." A place for faculty and students to trade ideas, plan meetings, agree and disagree. It was also a place for humor.

There was just one problem: many of the sarcastic jokes failed to land without a clear tone. Worse, things said in jest were occasionally interpreted as serious warnings.

On September 19, 1982, Fahlman proposed a solution. He was only half-serious:

I propose the following character sequence for joke markers:

:-)

Read it sideways. Actually, it is probably more economical to mark things that are NOT jokes, given current trends. For this, use:

:-(

It was, by some accounts, the first "smiley" ever shared. More than that, it is believed to be the first internet meme. It certainly acted in the manner expected, taking on a life of its own. Fahlman described the proliferation and evolution of his creation:

Within a few months, we started seeing the lists with dozens of "smilies": open-mouthed surprise, person wearing glasses, Abraham Lincoln, Santa Claus, the pope, and so on. Producing such creative compilations has become a serious hobby for some people.

Ingrained in common parlance, it's easy to forget that the word "meme" is a neologism, contrived by evolutionary biologist Richard Dawkins in 1976. In his work The Selfish Gene, Dawkins made his case for the invention:

We need a name for the new replicator, a noun that conveys the idea of a unit of cultural transmission, or a unit of imitation. 'Mímeme' comes from a suitable Greek root, but I want a monosyllable that sounds a bit like 'gene.' I hope my classicist friends will forgive me if I abbreviate mímeme to meme...

Some examples of memes are tunes, ideas, catch-phrases, clothes fashions, ways of making pots or of building arches. Just as genes propagate themselves in the gene pool by leaping from body to body via sperms or eggs, so memes propagate themselves in the meme pool by leaping from brain to brain via a process which, in the broad sense, can be called imitation.

Even its originator might have struggled to envision the scope the word would come to envelop. Recontextualized and super-charged by the internet, the term "meme" has come to hold meanings both particular and general, describing formally similar pictures and captions, dance moves, videos, stocks, and beyond. The meme is not necessarily limited to a specific idea, a "unit," but a cluster of multimodal media united by similar characteristics. Limor Shifman, a professor at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, has written one of the defining works, Memes in Digital Culture. She defines internet memes as follows:

[A] group of digital items sharing common characteristics of content, form, and/or stance, which were created with awareness of each other, and were circulated, imitated, and/or transformed via the Internet by many users.

Shifman's description sounds a lot like Roblox. In building an open platform that relies on user-generated content, Roblox has placed cultural power in users' hands and provided the means to create. The result is a concatenated but self-contained set of worlds governed by overlapping values, imbricated slang, and unified currency. Players of Adopt Me!, Roblox's largest game, can share jokes and judgments with Natural Disaster Survival players while still retaining localized cultures. Inventions in one world are remixed or subverted in another; memes made playable.

On Hacker News, one veteran Roblox player described his early experiences with the platform as follows:

Most of the games were mishmashes of pre-existing assets, puerile humor, and pop culture references. I remember one game in which you started off on a massive platform full of food, and had to shovel the food onto a conveyor belt that led into a giant person's mouth. If you yourself fell onto the conveyor belt, you'd be treated to a grand tour of the person's digestive system before being turned to poop and dropped into the toilet bowl. Inside the toilet, there was an obstacle course, and at the end of this obstacle course, there was an array of fighter jets that you could use to get back onto the food platform. The jets didn't have throttle: they either went super fast or not at all. So the poop-people would bail out of their planes in mid-air, and the jet would crash into the baseplate, usually killing someone below.

Though Roblox has, to an extent, matured from such scatological fever dreams, it retains the pattern of inheriting and borrowing, both from outside sources and other on-platform games. MeepCity, one popular title, directly appropriates Toontown and Club Penguin; Welcome to Bloxburg riffs on The Sims; minor games cadge and copy predecessors.

These worlds' vividness and scale have caused some to wonder whether Roblox is building a metaverse, a possibility the company references in its S-1. Roblox evokes Fornite or Unity with that framing, though its focus on user-generated content brings to mind traditional social media platforms. In truth, it is a company unlike any other: an amalgam of platform, studio, SMB tool, coding school, and micro-economy. It is both meme and meme-maker; YouTube granted an extra-dimension.

In its singular position, Roblox possesses unique strengths and vulnerabilities. The company has built a prosperous community among children but has yet to crack the adult market. It has enabled high-grossing, hit games but has failed to cultivate a long-tail of commercially viable alternatives. It has contrived a thriving endemic economy yet left both players and developers feeling bilked and manipulated. It has allowed millions to enter collective play, caused friendships to bloom, just as it has fumbled to shut down grooming, extremist groups, and virtual "lex" or "six" parties.

All of these factors make Roblox tricky to value. Adam Neumann was rightly laughed out of the room when he claimed WeWork's valuation relied on the business's "energy and spirituality." Yet, such a claim might feel plausible when discussing Roblox. More than almost any other, the company founded 16 years ago captures modern creativity's speed and strangeness, the fractal shape of contemporary communication.

We are living in an age of endless flux, of hypermimesis. In Roblox, investors may discover a corporate embodiment of that phenomenon.

Number of mentions in the S-1

Robux: 174

David Baszucki: 100

China: 56

Child or children: 48

Creator: 39

Tencent: 26

Luobu: 24

Human co-experience: 20

Metaverse: 16

Lua: 11

Erik Cassel: 6

Epic Games: 2

History

Roblox's journey did not begin in the world of games.

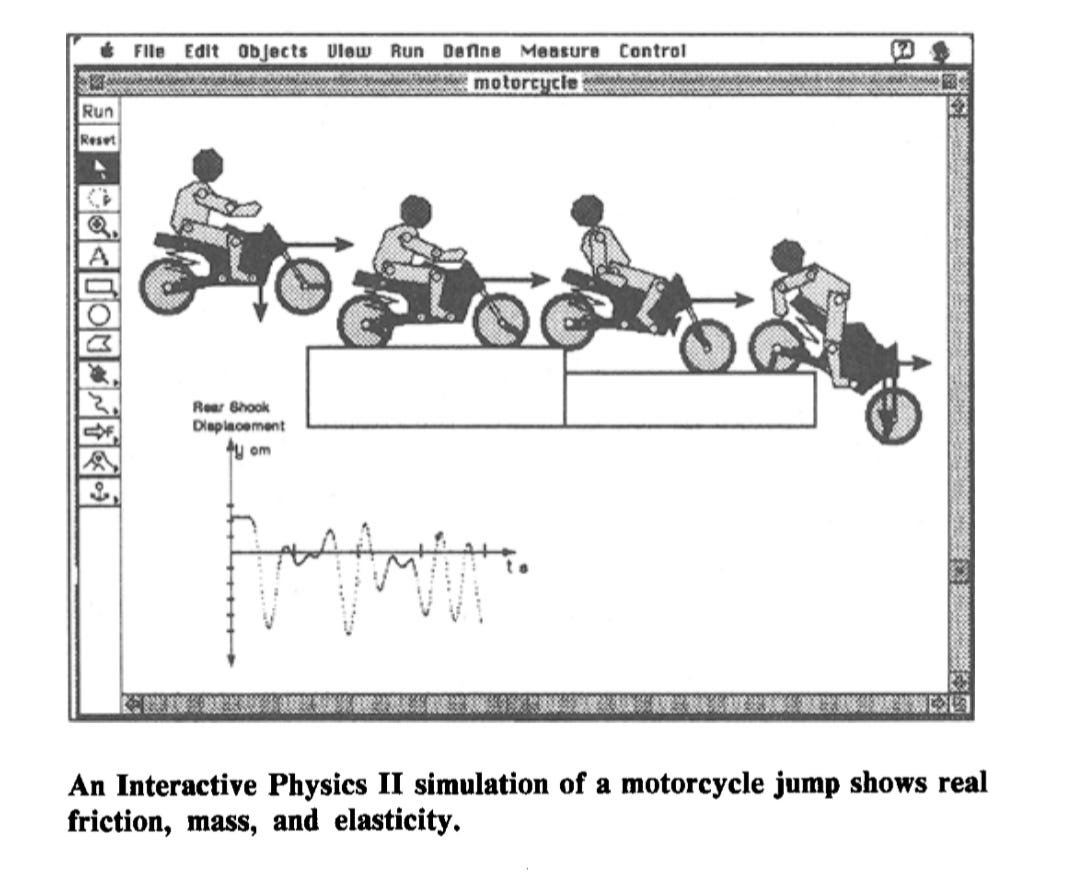

In 1989, brothers David and Greg Baszucki programmed a simulation tool called "Interactive Physics." It was designed as a sandbox for physics students to simulate motion, mass, friction, and more. Those that grew up in this era may remember it as an accidentally fun piece of software. Recalling that period, David Baszucki noted:

[U]sers of Interactive Physics software used it for fun rather than school! Kids would build all kinds of funny contraptions with the product.

To distribute their product, the Brothers Baszucki formed a parent business called Knowledge Revolution. After reading about the company in MacUser magazine, Erik Cassel flew out to interview. During his evaluation, Erik showed David and Greg a piece of simulation software he'd written for Cornell's physics department. The Baszuckis were sold: they'd found their new VP of Engineering, and though he didn't know it at the time, David had unearthed a future co-founder.

That time was to come more than ten years later. After Cassel joined in 1993, the trio grew Knowledge Revolution, ushering the company to a $20 million sale to MSC Software in 1998. The team stayed on for a few years after that before engaging in new pursuits. Greg founded a marketing business called Dealix, and David took to angel investing, funding Facebook-predecessor, Friendster.

Erik and David kept in close touch. Often the pair reminisced about the playfulness that Interactive Physics had encouraged. Perhaps there was a way to resurrect that, to super-charge it?

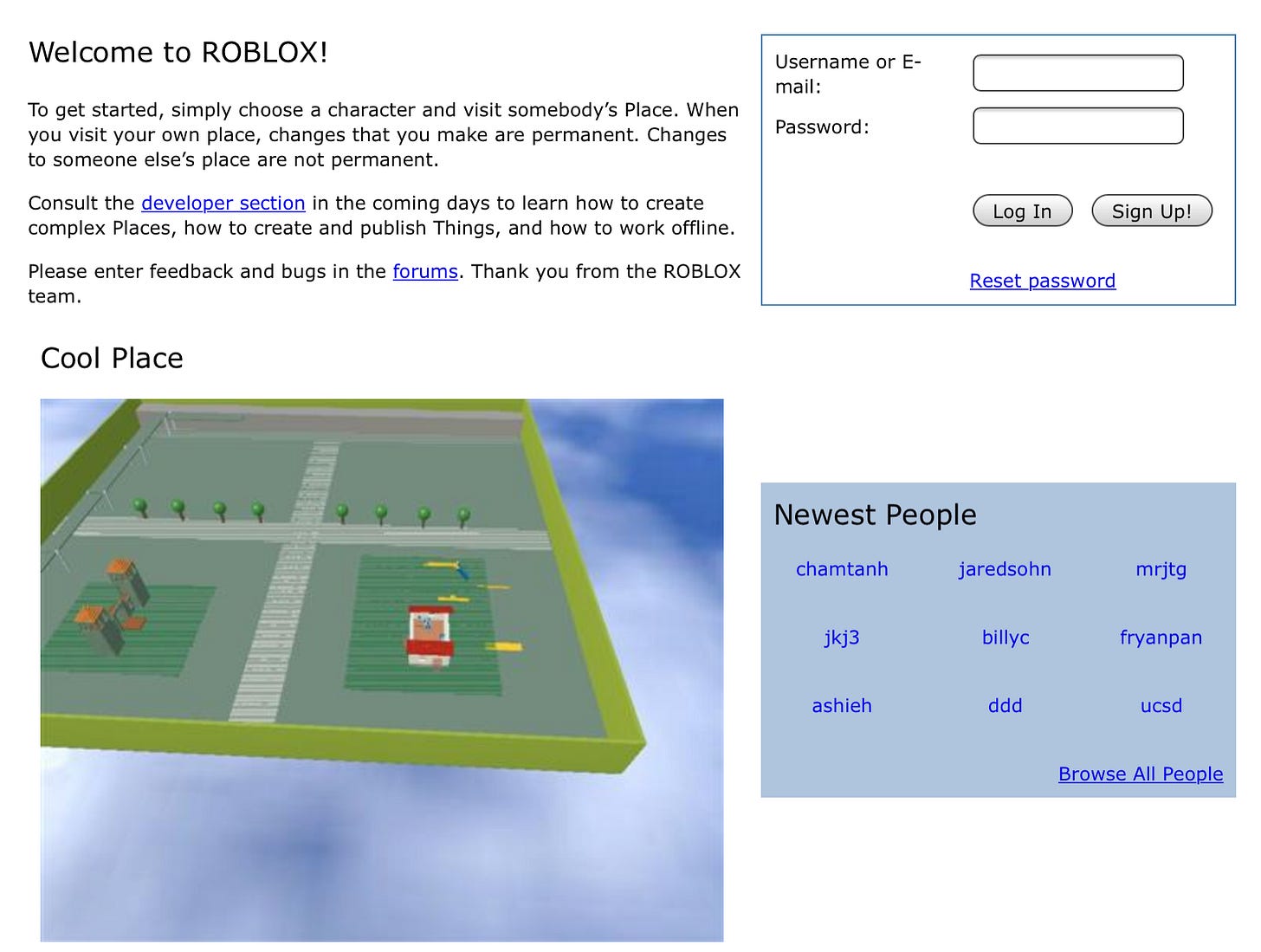

In 2004, David and Erik decided to take the plunge. For two years, they worked out of an office in Menlo Park on a project they christened "DynaBlocks," before adopting Roblox shortly after.

Roblox was a natural extension of David and Erik's work with Interactive Physics, though even more open-ended. The goal was to provide the building blocks to create a world. In that vision, and the name and aesthetic Roblox pursued, it explicitly evoked "digital Legos." Roblox's early websites made it clear there was no affiliation between the two companies to avoid legal issues.

Unlike today, the original iterations of Roblox were not focused on standalone "games." Instead, users could choose from a variety of "places" to create and visit.

Over time, experiences were added to these virtual hangouts. An early example is "Crossroads," a "BrickBattle" game developed by the Roblox staff and released in 2006. Bit by bit, more experiences crept into the world of Roblox, eventually evolving into the games at the heart of the platform today.

As you might expect, given David and Erik's background in building educational software, much of the early Roblox community was composed of children and young adults. As a result, Roblox became COPPA compliant early in its life and even had a dedicated set of resources on its site for parents, explaining its educational advantages and touting its safety.

Roblox raised relatively little capital in its early years, with its "Series C" pulling in $2.9 million. It is likely no coincidence that in 2017, the year after Baszucki noted that Roblox was "starting to see a network effect," the company announced its first growth round: $25 million from Index Ventures and Meritech Capital Partners. From then on, more than a decade after its founding, Roblox entered the kind of warp-drive enjoyed by many other tech unicorns. Over the following years, Roblox raised a mind-boggling $820 million in private financing.

Notably, the largest influx arrived at the start of 2021. After watching the run-ups of Airbnb and Doordash, Roblox seemed to believe there was significantly more juice that might be squeezed out of their IPO should they engage in a re-pricing exercise. To tide them over, Altimeter Capital and Dragoneer Group invested $520 million. At first blush, that looks a savvy move. While December's commentary postulated an $8 billion valuation — double their last private round — the January influx pegged the business at $29.5 billion. A new floor has likely been set.

Roblox's product has mostly kept pace with the size of its coffers. After frequent outages, the company renovated its infrastructure in 2017, which seems to have improved matters, though issues remain. Platform expansion also appears to have been a priority: Roblox is available across Xbox, PC, iOS, Android, and VR headsets. The platform currently requires high-bandwidth data capabilities, but as consumer computing devices grow more powerful (and cloud computing expands), global access should only increase.

Today, the company boasts 31.1 million daily active users (DAUs) and 18 million "experiences." Like Fortnite, the company has dabbled with more divergent virtual experiences, hosting a concert with Lil Nas X in November of last year.

Despite its progress, Roblox has held onto much of its original spirit. The avatars look a bit less like Lego characters, but much of the DIY, open-ended ethos is still there in the experiences and community. As the company actively courts users outside its core demographics, it remains to be seen whether this vision will represent an aid or impediment to future growth.

Market

Gaming

There are few markets more attractive than gaming. The fastest-growing sector in media, gaming is growing rapidly compared to the music and film industries. In particular, the medium appeals to a younger demographic, meaning that a larger percentage of consumers are added to the 2.5 billion already ensconced in states of digital play with each new generation.

Critically, games also have high re-playability. While few Netflix shows are consumed more than once (and those that are, like The Office, are considered extremely valuable), there is no maximum amount of time you can spend in an evergreen 3D world.

The video game industry was estimated to be worth $159.3 billion in 2020, with the market growing 9.3% year-over-year (YoY). Critically, the space is accelerating much more quickly than initially projected; by 2023, it is predicted to reach $200 billion.

Importantly for Roblox, most revenue comes from "free-to-play" games, those that upsell users as part of their interaction. Fully 85% of gaming revenue arrived through games of this type, the model favored by most Roblox developers.

Roblox does not hazard a guess at its market size in the filing, perhaps because the broadness with which it sells its opportunity makes the potential of the business clear. In several places, Roblox describes its goal as owning "human co-experience":

Together users will play, learn, communicate, explore, and expand their friendships, all in 3D digital worlds that are entirely user-generated, built by our community of nearly 7 million active developers. We call this emerging category "human co-experience," which we consider to be the new form of social interaction we envisioned back in 2004. Our platform is powered by user-generated content and draws inspiration from gaming, entertainment, social media, and even toys.

Another way to understand Roblox's market is to observe the companies to which it is most similar. As noted previously, the company combines elements of social networks, toys, and 3D engines.

A few relevant comparisons, at the time of writing, with this in mind:

Lego: $7 billion valuation

Facebook: $740 billion market cap

Activision Blizzard: $61 billion market cap

Unity: $41 billion market cap

All of this to say that Roblox has the ingredients to both capture, and create, an extraordinarily large market. While Boomers and Millennials have leveraged Facebook and Instagram to connect, and Gen-Z has chosen Snapchat and TikTok, Gen Alpha are increasingly building their social graphs in synthetic realities.

Roblox's focus on user-generated content (UGC) is key to manifesting and capitalizing on the opportunity. Just as UGC radically expanded the total addressable market for video via platforms like YouTube, it may have a similar effect in the gaming space. The boost UGC provides may be even more pronounced, given gaming's powerful network effects. A UGC-primed flywheel in gaming could yield seismic results, namely, the creation of the metaverse. Roblox mentions the term 16 times in its prospectus.

Some refer to our category as the metaverse, a term often used to describe the concept of persistent, shared, 3D virtual spaces in a virtual universe. The idea of a metaverse has been written about by futurists and science fiction authors for over 30 years. With the advent of increasingly powerful consumer computing devices, cloud computing, and high bandwidth internet connections, the concept of the metaverse is materializing.

Though Roblox isn't there yet, it is undoubtedly one of the most credible early expressions. Given the nascency and amorphousness of the metaverse as a market, sizing it is tricky. But safe to say, it's large. Digital realities could become a plausible interface for plenty of real-world activities, from school graduations to work meetings, movie screenings, concerts, and e-commerce. New goods, services, and experiences beyond current imagination will also be unlocked.

If you believe Roblox has a chance to win this world, the upside (for both players and developers) is virtually (ahem) unlimited.

Demographics

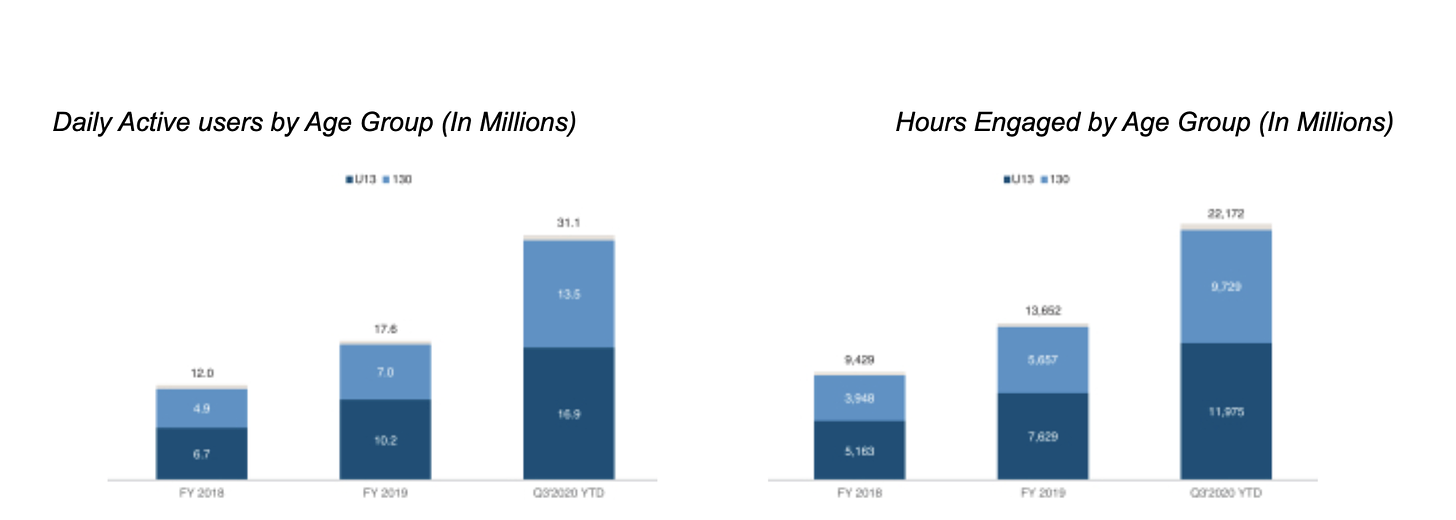

Roblox's user base skews young. Of the company's 31.1 million DAUs, 54%, or 16.9 million, are under 13 years old. This represents a falling majority compared to previous years: in 2019, 58% of users were under 13, and in 2018, 55% fell below this line. According to some reports, a staggering 50% of nine to 12-year-olds in the United States and Canada, New Zealand, and Australia, play either Roblox or Minecraft, which indicates how effectively the company has captured this market.

This focus comes with its challenges. Like all social platforms, Roblox requires robust moderation software and support. Serving minors only exacerbates the importance of this function and the risks that can arise from failure.

Parents have reasonably complained about their children receiving violent sexual messages through the platform. Grooming and the congregation of extremist groups are also real problems. Roblox has sought to combat this with stringent text-filtering (hence, "six" parties), audio scanning, and image detection technologies. In 2020, human customer support agents responded to 9 million inquiries within an average of ten minutes of submission.

Maintaining its reputation as a benign, vaguely educational platform will rely on Roblox minimizing distressing incidences like those described above.

Increasing its proportion of users over the age of 13 may cause further problems. Will the platform age-gate different instances of a game? If so, how will it ensure such a policy is effectively implemented? Trash talk or attempts at friendship may look very different depending on whether users are 13 or 30.

The company will need to find a solution. To continue growing, Roblox must increase its share in older demographics — both by retaining existing customers as they age and winning new users. The S-1 notes that users above age 13 have a "higher propensity to spend on content," making them particularly valuable. Roblox will hope that residing in virtual worlds loses its stigma over the coming years and that its experimentation with slicker aesthetics will appeal to a more mature audience. Encouragingly, Roblox reports that in the first nine months of 2020 (hereafter referred to as FY20), the cohort of 17 to 24-year-old users grew faster than the core under 13 age group.

It will be interesting to see how such a shift might affect hours spent on the platform. While parents often limit children's playing time, adults may be less stringent policers of their own leisure. Adult users may also attract a more mature, experienced class of developers, which could aid game creation. As it stands, the distribution of hits on the platform is highly concentrated, with a handful of blockbusters: twenty games on the platform account for 1 billion plays. If such a dispersion holds steady, developers may find Roblox an unpalatable destination for their latest endeavor. Bringing new types of users onboard may open up space for more niche appeal.

If that happens, the Roblox flywheel may begin to pick up pace: more users spending money drives more developers to the platform which brings more users.

The China JV

Much of Roblox's expansion plan seems to rest on a convoluted joint-venture in China. The Asia Pacific region is home to 48% of the world's gamers, with a $72.2 billion market size as of 2019. Given China's hostility toward US tech giants, Roblox has savvily sought entrance via a partnership with Songhua River Investment Limited, a Tencent subsidiary.

The structure of this agreement is best summarized as follows:

Tencent and Roblox have joined forces to create "Roblox China Holding Corp." This is referred to as the "China JV."

Roblox owns 51% of the China JV, while Tencent owns 49%.

Roblox holds this stake via a local subsidiary called "Roblox (Shenzhen) Digital Science and Technology Co.," branded as "Luobu."

Tencent is charged with securing licenses and publishing Roblox's game in China, under the name "Luobulesi."

The plan seems to have worked. In December, Tencent received two licenses from the Chinese government, smoothing its path to launch Roblox in the country. This may have served as another reason to delay and re-price its filing. With China opening its doors, Roblox has secured access to a massive, influential market.

Product

Roblox is more than just the game that millions of users play every day. It's a trio of products that interact to form an ecosystem: the Roblox client, Roblox Studio, and Roblox Cloud Services.

Roblox Client

The Roblox Client is the game as the user experiences it. As noted, it's available across many different platforms (including mobile ecosystems like iOS and Android) and is free to download. The ease with which Roblox can be accessed has been critical to the consistent growth of the business.

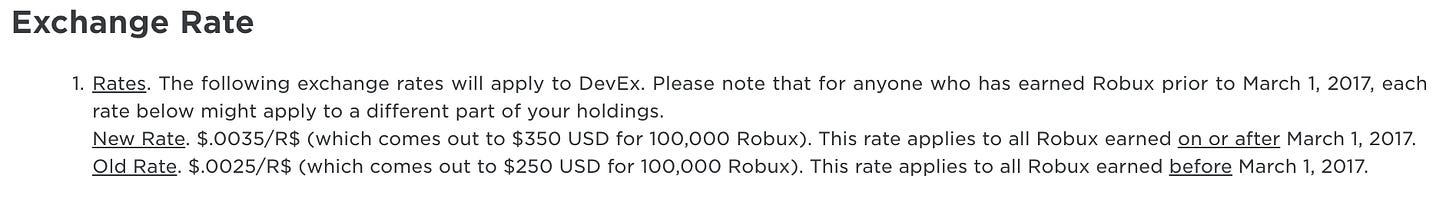

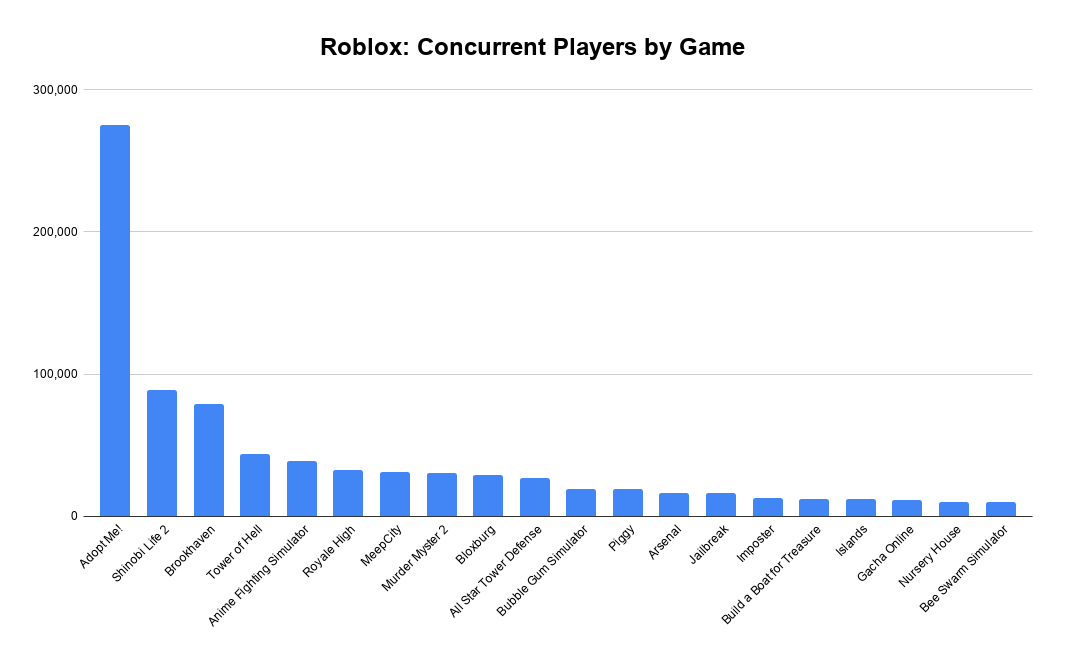

Users can interact with 18 million user-generated experiences from the client, though fully 6 million have never been played. As mentioned, there is a rather top-heavy distribution on the Roblox platform, with Adopt Me! — a simulation in which users raise a virtual pet or child — occupying 23% of concurrent users (CCUs).

The next five most-popular games garnered a further 30% of CCUs. All games are tied together via Roblox's social network, making it easy for users to join their friends in play. They tend to be rather innocent (at least, outwardly) in terms of aesthetic and gameplay.

As is the case with other UGC platforms (think Facebook or YouTube), discoverability is critical. Roblox is no different. As it stands, users are often presented with games played by their friends, with the social graph doing the curational work. However, there's room for improvement when it comes to recommending games based on interest. It will be intriguing to see if Roblox devotes further resources to solve this problem, particularly when considering the effect that intelligent suggestions like those leveraged by Facebook's algorithmic feed super-charged growth.

A few popular games that shed light on Robloxian culture include: Adopt Me!, Royale High, Welcome to Bloxburg, and Murder Mystery 2.

Adopt Me!

Roblox's #1 game is essentially a baby simulator. Players choose to be a parent or a baby, with items available to purchase to decorate one's avatar or speed up progress. Parents work to take care of the baby, and babies get to enjoy such riveting activities as "eating." The game has reportedly been used as a "dating app" against Roblox's terms of service. Indeed, "Adopt Me dating" seems to have emerged as a rather unique subculture on TikTok and YouTube — what better way to test whether your relationship will work than raising a "Mega-Neon" child together.

Royale High

A high school-themed game where players role-play fairies, mermaids, and other magical creatures. Users can star in talent shows, explore fantasy locales together, and relax by the pool. This game started as a Winx Club fan game and was built by a single creator.

Welcome to Bloxburg

Owing much of its DNA to The Sims, Bloxburg lets users live. They can build their own homes, go to work, hang out with friends, explore the local city, or cut a rug at "Beat Nightclub."

Murder Mystery 2

Based on a Garry's Mod game-mode called Murder, this Roblox favorite is similar in play to classics like Mafia and Werewolf. One player takes the role of "Sheriff," one takes the part of "Murderer," and up to 10 remaining players take the role of "Innocents."

The Murderer seeks to kill all Innocents without getting caught, while the Sheriff looks to stop the Murderer. The Innocents witness murders and pass information to help the Sheriff make their arrest.

The long tail

Aside from these popular experiences, there's an extensive long tail of user-created games and experiences accessible inside the Roblox client. Many are effectively copies of other popular games, memetic twists on old favorites.

There are (more) clones of hits like Among Us, first-person shooters that emulate classics like Counterstrike, and other titles that mimic Roblox's homegrown winners. Adopt Me! is far from the only baby simulation game, for example.

Roblox Studio

Roblox's second major product is a suite of tools that enables "creators" and "developers" to build new experiences and digital assets.

Though still complex, Roblox Studio offers a relatively easy way for beginners, including kids, to create a game from scratch. The platform leverages Lua, described as a "light-weight programming language popular in the gaming industry." Developers can use objects from the Roblox universe in their games, further streamlining development efforts.

The choice of Lua has roots in the Roblox founders' background in educational software. As noted, the language and toolset have been designed to be reasonably accessible and is even a part of some schools' programming curriculum. On this subject, Roblox acquired a company called Ceebr Limited that helps teach Roblox development for kids.

In our experience, Studio is not the most performant piece of Roblox's empire. Bugs and shutdowns plagued our experiments with the software.

From our research and limited first-hand experience, once signing in, developers are instructed to pick from a selection of templates including "Flat Terrain," "Boilerplate," "Combat," "Volcanic Island," and several others. Once selected, the user is dropped into this barebones but navigable world. Within this environment, users can place and manipulate objects — blocks, trees, water — and script logic. Bit by bit, the user can build up a complex, ludic environment.

Roblox Cloud

Roblox's final product is a set of cloud services that developers can access alongside building experiences in Studio. Roblox Cloud handles the localization and translation of in-game assets to help games scale across geographies when deployed in Roblox. At the moment, Roblox manages this translation across 11 languages via "machine translation and advanced pattern recognition."

Beyond this service, Roblox Cloud offloads computing to the cloud, providing a better cross-platform experience. This is particularly pivotal as 68% of engagement hours over FY20 came from users registered via the Apple App Store or Google Play Store. The suggestion is that a majority of gameplay occurs on mobile devices. To ensure that experience is smooth, cloud-based infrastructure is necessary.

Business Model

In thinking about Roblox as a business, it's essential to highlight the two distinctive use cases that it facilitates: "Build" and "Play." Roblox operates both as a game development platform (build) and game discovery and account management client (play). As described above, the content that Roblox players interact within the client is created exclusively with Roblox's development software and is only available to be played through the Roblox client. Roblox's unique business model exists at the confluence of these two use cases, with user-generated content monetized by the developers that create it, serving as the commercial undercurrent of the ecosystem's economy.

Developers create games with the Roblox development platform, and those games are made available to other users in the Roblox client. The client includes a store in which players can purchase a hard currency called "Robux." Robux packages are available as either one-off purchases (e.g., 80 Robux for $0.99) or as subscriptions that offer better value than similarly-sized packages (e.g., a 450 Robux subscription for $4.99 per month, versus 400 Robux for $4.99 as a one-off purchase). These Robux purchases can be made in the client across platforms (iOS, Android, desktop, Xbox), but critically, pricing differs for each platform. For instance, the Roblox website offers Robux packages at a higher value (in terms of Robux per dollar) and higher package volumes than those available in the Roblox iOS app. Roblox does this because it keeps close to 100% (excluding transaction fees) of the money it generates from web sales but has to share revenue generated on other platforms. Specifically, both iOS and Android stores take a 30% cut.

When a user buys Robux (either as a one-off purchase or subscription), the currency is deposited into a virtual wallet. It can be spent in several ways:

Cosmetic upgrades to the user's avatar. Every Roblox account has an associated avatar, which can be "upgraded" or customized with various decorative accessories. This includes clothing and gear and body composition components such as arms, head, torso, and skin tone. These avatar upgrades used to apply at the account level, but now individual games can sell cosmetic upgrades to the avatar that only apply in those games. This helps game developers and Roblox monetize users many times over.

In-game content. Most free Roblox games allow players to alter the in-game experience through passes that offer time-limited or persistent perks and through one-off purchases of virtual goods.

Games access. The vast majority of games within the Roblox ecosystem are free-to-play, but access to some must be purchased with Robux.

Roblox makes money when users buy Robux; the company also operates an advertising network within its game discovery platform, but it indicates in its S-1 that this revenue represents a "minimal dollar amount." Developers on the Roblox platform make money by amassing Robux in several ways:

Selling in-game content to users, as described above.

Allowing players to purchase avatar accessories and upgrades from within their games.

Operating private VIP servers that players must pay to access.

Charging an entry price to play their games.

Earning Premium Payouts, which rewards developers with Robux based on Premium subscribers' time in their games.

Roblox offers a revenue share mechanic to game developers to redeem the Robux generated by their games for USD. Still, the economics of that revenue share arrangement are somewhat opaque and are heavily skewed in Roblox's favor.

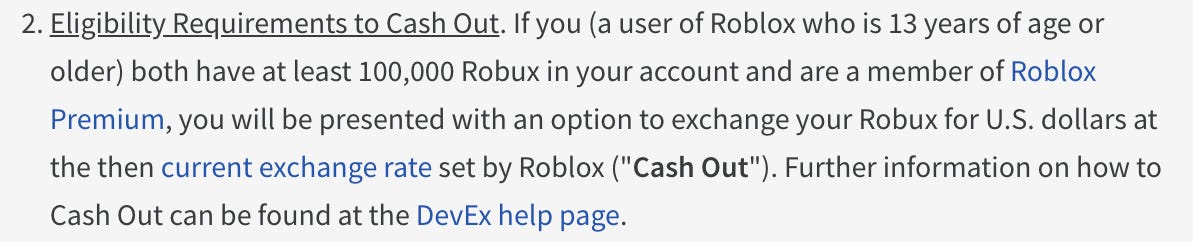

First, Roblox dispenses revenue to developers in the form of Robux: a developer's Roblox account is credited with some proportion of the Robux it has generated (70% for in-game content, 30% for Avatar upgrades). Then, Roblox allows developers to exchange those Robux for USD at a rate (the "DevEx" rate) set by Roblox at $0.0035 per Robux. This exchange rate effectively creates a Robux-to-USD conversion tax that further reduces the percentage of game revenues that a developer receives.

Roblox's website pegs the average developer share of game revenue at 24.5%. This popular thread on the Roblox community forum puts the average developer share of games revenue at less than 20% (in the example below*, the developer share is 19.7%). In any case, the developer economics on Roblox are vastly different than for other games publishing platforms, such as Valve's Steam or even the iOS App Store, which tends to take a 30% platform fee on revenues.

Example: If a player were to buy 80 Robux for $0.99, their purchase price is $0.0124 per Robux. If that player were to spend those 80 Robux in a developer's game subsequently, and the developer redeemed them for $0.0035 per Robux, the developer would receive $ 0.0035 / 0.124, or 28% value of the Robux package that was purchased by the user. Reducing this amount by the 30% platform tax puts receipts to the developer at 19.7% of total revenue generated. Yikes.

The developer economics within the Roblox ecosystem may engender headwinds that slow the developer pool's slow growth at some point. One current issue Roblox faces is extreme concentration in engagement within the top games on the platform, a problem identified earlier in this piece. As of November 29, 2020, the distribution of concurrent players across the Top 20 games on the platform is represented below:

This kind of concentration is unhealthy for a content ecosystem, creating a "winner-takes-all" dynamic that starves titles of engagement. In turn, it dissuades new developers from devoting time to the platform. Note that every freemium content platform features a long tail distribution of content engagement. Still, the degree to which the above distribution is left-skewed is troubling: the top game, Adopt Me!, has more than 3x the number of players than the second-most-popular title, Shinobi Life 2.

The existing developer economics of the Roblox creator ecosystem reinforce this dynamic by disincentivizing investment from professional developers into the platform. Specifically, the unfavorable revenue split discourages sophisticated developers from investing in Roblox because the platform's terms preclude:

Paid user acquisition. Given the small share of revenue received by the developer, it is likely unmanageable to profitably grow a game to a meaningful scale using Roblox's advertising tools, given that the developer bears all marketing costs.

Significant upfront development costs. The more ambitious a project, the more it is likely to cost to develop. Yet, large, sophisticated studios are potentially repelled from the Roblox ecosystem relative to other ecosystems that offer better developer economics for publishing.

COGS. Any variable expenses, such as IP licenses that are generally paid out as a percentage of revenue, are difficult to support given how little money the developer is taking from game revenues. This means developers that have the opportunity to work with big brands and IP licensors will publish elsewhere.

Roblox can mitigate these issues by offering improved game discovery, investing in robust advertising tools and infrastructure, and altering developer economics. On the latter point, Roblox could follow in Steam's footsteps and reduce the platform fee as game revenues increase.

Each of these approaches would incur costs, and reducing platform fees would create a revenue shortfall to serve the long-term objective of growing the creator pool. Strangely, Roblox's S-1 seems to suggest the company believes they are keen to sacrifice short-term gain to create a vibrant developer ecosystem. One of the company's core values is "Take the Long View." Later, the filing notes:

A significant part of our business strategy and culture focuses on long-term growth and developer, creator, and user experience over short-term financial results. We expect our expenses to continue to increase in the future as we broaden our developer, creator, and user community, as developers, creators, and users increase the amount and types of experiences and virtual items they make available on our platform and the content they consume, and as we develop and further enhance our platform, expand our technical infrastructure and data centers, and hire additional employees to support our expanding operations.

What's concerning here is that Roblox believes (or would like us to believe) it's already making the necessary short-term sacrifices, perhaps illustrating a detachment from the reality of its brutal take rate. Underestimating this risk could prove foolish; maintaining the status quo could cause the creator class to stagnate and ultimately throttle user growth.

Management

A discussion of Roblox's management team can only begin in acknowledging an absence. Co-founder Erik Cassel passed away in 2013, with David Baszucki chronicling their founding story and describing Cassel's remarkable engineering gifts.

Baszucki himself appears to be well-liked by his staff, with 98% approving of the CEO and 78% noting they would recommend working at the company to a friend.

Though Roblox is a comparatively old business — at least by tech standards — much of its leadership is new. Indeed, Roblox's CTO, CFO, CBO, and CMO are all recent additions. Interestingly, none of these executives bring a gaming background to the table. Only when one reaches China czar, Ari Staiman, and Christina Wootton, VP of Brand Partnership, is sectoral expertise demonstrated.

Instead, the company seems to have indexed on retail and online shopping, with a minor in social networks.

David Baszucki, CEO. As mentioned, David previously co-founded Interactive Physics alongside brother Greg, which sold to MSC Software.

Daniel Sturman, CTO. The right man at the right time, Sturman arrived in early 2020, leaving his position as SVP of Engineering at Cloudera. Before that, Sturman was a VP of Engineering at Google. Both experiences should stand him in good stead as he tries to improve the occasionally temperamental infrastructure undergirding Roblox.

Craig Donato, CBO. Coming from Nextdoor, Donato has experience in the social space, though admittedly of the more terrestrial variety. Before his stint as VP of Business Development, he founded Oodle, a localized online marketplace acquired by QVC.

Barbara Messing, CMO. Brought aboard in August of last year, Messing was previously employed as SVP and CMO of Walmart. Before that, she served as CMO of TripAdvisor. In addition to that work, Messing previously served on the board of Mashable and XO Group; she currently sits on the board of Diamond Resorts and Overstock.

Remy Malan, Chief Privacy Officer. Malan is tasked with the unenviable job of helming Roblox's "Trust & Safety" division. This appears to be a departure from much of his prior work, with his last position as Chief Customer Officer of SugarCRM. Before that, Malan was a VP of Sales at a workforce management business. The complexity of Roblox's moderation needs should represent a somewhat different proposition.

Michael Guthrie, CFO. Before joining Roblox, Guthrie served as the CFO of TrueCar, an online automobile marketplace. Before that, he worked as SVP of Business Development at SharesPost.

Ari Staiman, President of Roblox China. Before matriculating into his current role, Staiman was Roblox's Global General Counsel. Before that, he was a GM of China and Ireland for Borderfree, an e-commerce business that IPO'd in 2014. Nearly a decade spent at SEGA — both with the core business and in the company's parks division — provide the most direct gaming expertise of upper management.

Kyle Price, Head of Corporate Development and Chief of Staff. Price comes from eBay, where he also operated as Chief of Staff for the Americas. If Roblox attracts the lofty valuation many expect it to, Price may be particularly busy.

Jonathan Vlassopulos, Global Head of Music. Vlassopulos has had an eclectic career as an angel investor, serial founder, and media executive. Before joining Roblox, he founded Tribalist, a Pinterest competitor.

Christina Wooton, VP of Brand Partnerships. Wooton appears to have risen through the ranks, starting as a Director of West Coast Sales in 2014. Before that, she served in an equivalent role at Glorious Games Group, maker of Stardoll.

Chris Misner, President of Roblox International. Misner's LinkedIn suggests he has cycled out of this role with his current position listed simply as "Advisor." Before his stint at Roblox, Misner was GM of APAC for Apple's Online Store.

Though it may represent too close a reading, Roblox's management seems particularly suited for one particular task: online monetization. Already, the platform's games are stuffed with upsells and prompts to purchase. Users may find this practice made even more prominent in the years ahead.

Investors

If you were looking to paint a picture of venture capital's trajectory over the last 15 years, you would be hard-pressed to find a better company to use as a canvas than Roblox.

The company's rise started at a time of scarcity in the early stage capital market, something doubly true for the perceived-to-be niche category of gaming. The first outside investor in Roblox was Altos Ventures, the largest external shareholder at IPO. Pitchbook notes that First Round Capital was also involved relatively early, investing roughly $3 million at a pre-money valuation of just $6 million. As First Round founder Josh Koppelman recounted in a recent interview, the firm initially passed on making the investment before digging in deeper and making the now-lucrative call.

As the venture capital market grew louder over the ensuing decade, Roblox stayed quiet. As noted, the company raised just $11 million in its first 12 years of operation.

In 2017, with the mass market potential for gaming starting to come into clearer view, Roblox hit the fast-forward button on fundraising. A $25 million round from Meritech Capital and Index Ventures was followed in short order by a capital infusion from Greylock and Tiger Global, valuing the company at over $2 billion. Earlier this year, Andreessen Horowitz, along with names like Tencent and Temasek, entered the fold for the first time in a Series G round that pushed the company's valuation to approximately $4 billion.

As mentioned earlier, Roblox elected to delay its IPO, initially expected in December of 2020. Instead, in January of 2021, Roblox announced that it had raised $520 million from Altimeter and Dragoneer, valuing the company at $29.5 billion. That sharp uptick in valuation may reflect tech's performance in the public markets and the de-risking of the China JV.

Though a revised cap table has yet to be shared, Roblox's initial S-1 filing noted that five investors cleared the 5% threshold. Altos Ventures held 23.9% of Class A shares, First Round owned 7.0%, and Index Ventures' share stood at 11.1%. Meritech held 11.6%, and Tiger Global owned 8.2%. Like so many other tech businesses, Roblox is leveraging a 20:1 dual-class structure, ensuring CEO Baszucki has voting power.

Financial highlights

ASC 606 and why Roblox's GAAP financials are a lie

First, a quick digression on the basics of revenue recognition under Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP). A new standard called Accounting Standards Codification 606 (ASC 606) became effective for most public companies in 2019. ASC 606 significantly changed how many businesses, including most gaming companies, report their revenues. Unfortunately, while the rule was intended to help companies more consistently evaluate their performance obligations to their customers, gaming companies are not well-served by these changes.

The precise details of this accounting rule are boring and not super important, but to understand Roblox's financial profile, it is essential to know how the rule impacts their accounting. Here's the punch line: ASC 606 turns Roblox's GAAP financials into gobbledygook because the rule requires Roblox to amortize (spread) revenues from users who buy virtual currencies like Robux over time, under the premise that they have an ongoing obligation to the customer.

This is where you, a savvy and diligent digital consumer, will no doubt immediately protest. "But I've carefully read Roblox's Term of Service, and that's not true! They have no obligations! It says so, in like, a million places!"

We reserve the right to modify or discontinue the Service at any time (including by limiting or discontinuing certain features of the Service) without notice to you. We will have no liability whatsoever on account of any change to the Service.

No Obligation. Neither us nor any third party has any obligation to exchange Robux for anything of value, including, but not limited to, real currency, except as expressly provided in these Terms or otherwise required by applicable law. We, in our sole discretion, may impose limits on Robux, including, but not limited to, the amount that may be acquired, earned, or redeemed.

Valuation of Robux. You acknowledge and agree that we may engage in actions that may impact the perceived value or acquired price of Robux at any time, except as prohibited by applicable law.

Absolute Right. We, in our sole discretion, have the absolute right to manage, modify, suspend, revoke, and terminate your license to use Robux without notice, refund, compensation, or liability to you, except as otherwise prohibited by applicable law. We make no guarantee as to the nature, quality, or value of Robux or the availability or supply thereof.

You are 100% right. All gaming companies make sure players agree to these terms before playing. Roblox could shut down tomorrow, and your precious, precious Robux would go poof, and there would be nothing you could do. But for accounting purposes, the lack of an explicit obligation doesn't matter since Roblox has made an implied promise to continue displaying Robux for use in the game via its customary business practices. That implicit promise is good enough for ole' Deloitte & Touche.

At this point, you, a voracious digital dolphin who knows a good deal when you see it, might say, "Okay, well, I guess maybe I believe there is some implicit promise made when players buy virtual currencies, but surely the revenue should be recognized when players use their Robux. After all, once I gleefully and irresponsibly spend all my Robux, doesn't Roblox's obligation to me end?"

Oh, sweet summer child, the accountants are smarter than that. They realize Robux is not really "consumable" items that vanish once spent, leaving you with nothing but regret and a fleeting dopamine rush. They know that when you splurge your Robux on a Legendary Robo Dog or a cunningly wrought imitation of the Eerie Pumpkin Head, that rarest of hats, you're really investing invaluable digital heirlooms you might pass on to your baby brother when he one days gets old enough for his own iPad. Roblox's implicit obligation to serve you, therefore, transfers to those "durable" items. As such, Roblox must amortize its Robux bookings over the expected life of their customers, which Roblox helpfully (and probably misleadingly) defines in the filing as 23 months (more on this below).

This dynamic plays out in some fashion for all public market gaming companies, especially those that traffic in live-service free-to-play games. Each has its special snowflake customers, and each has its own carefully thought out and not-at-all arbitrary assessment of which virtual goods are consumable and durable. Therefore each amortizes bookings over a unique estimated customer lifetime. So, when you see Roblox report GAAP of $589 million in 2020 year-to-date revenue, with a $203 million net income loss, and then morosely apologize that its net losses will continue in the future, spare a thought for poor Mike Guthrie and safely ignore all those numbers They're not only an imaginary and inaccurate representation of Roblox's actual economic performance, they're also not helpful on a comparative or relative basis to other gaming companies.

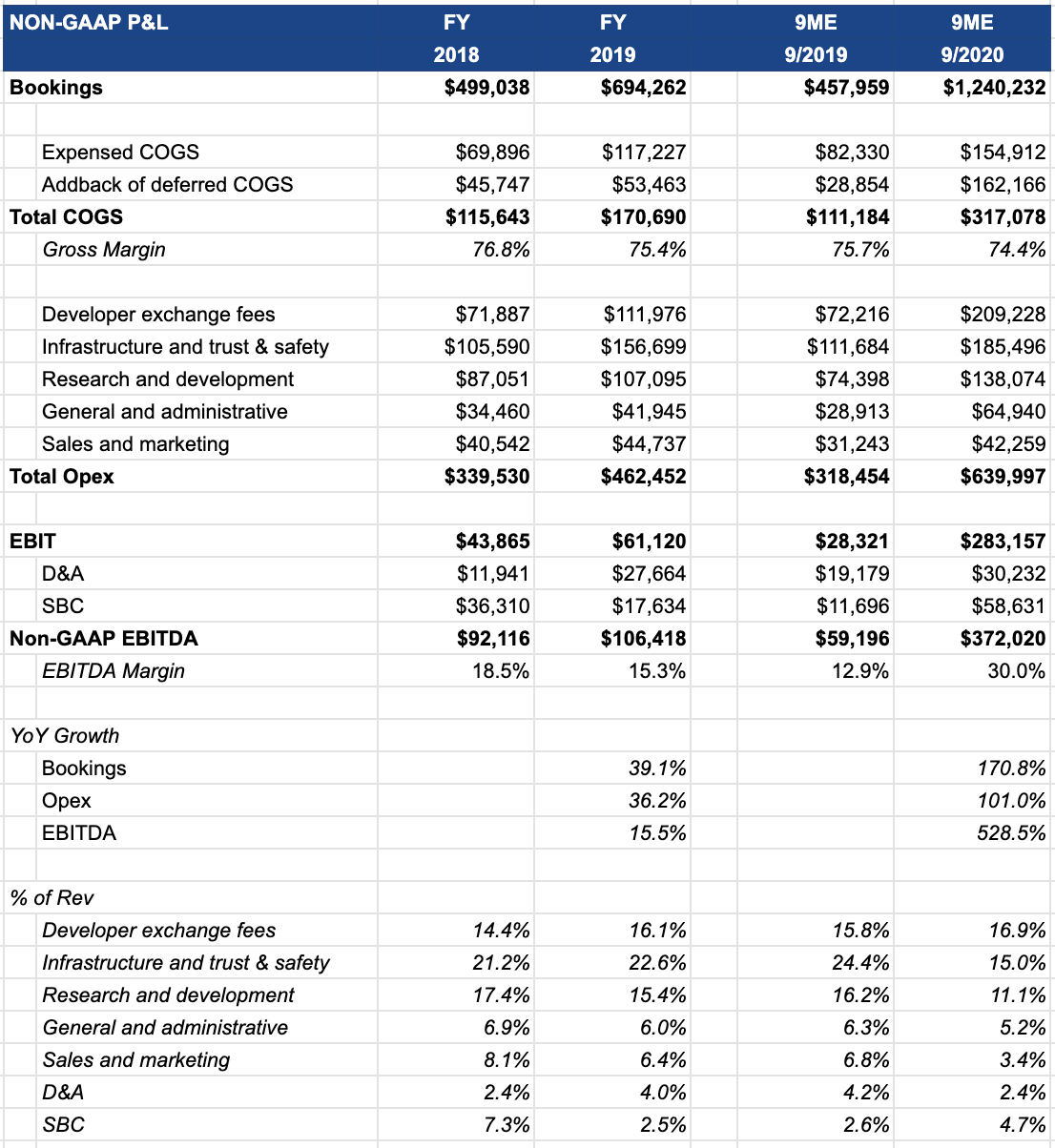

This is why the market will value Roblox and assess its ongoing performance on a non-GAAP basis, which will substitute bookings for revenue and add-back deferred expenses. There is no "right" way to do non-GAAP, but the paper napkin financial model will likely look something like this:

Explosive topline growth

So, what should we pay attention to among Roblox's numbers?

The most eye-catching figures are related to the company's topline growth. It exploded in 2020, with year over year increase in revenue of 171% over FY20.

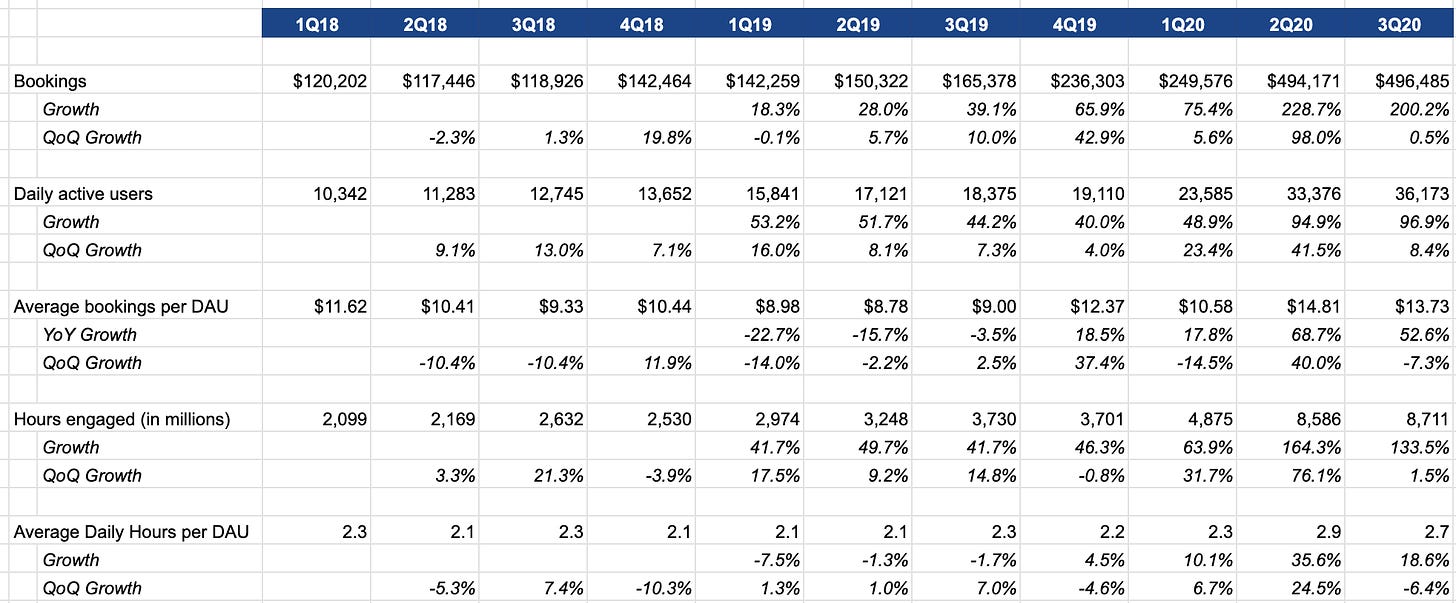

The quarterly view helps us understand where that growth is coming from. The company was already showing an acceleration in bookings coming out of 2019, driven by increases in per-user monetization, which offset a slight deceleration in DAU growth. However, covid-19 provided the business with rocket fuel, as both DAU and average bookings per DAU (ABPDAU) exploded in the second quarter.

We can see in the quarterly financials that the covid tailwinds moderated slightly in the 3Q. While YoY trends still look great, the quarter-over-quarter (QoQ) view shows some deceleration. Per-user hourly engagement declined 6.4%, and ABPDAU dropped 7.3%. DAUs sequential growth, at 8.4%, was more in line with historical growth rates.

This deceleration is expected, and the insane performance of mid-2020 will likely create some tough comparisons for Roblox (they are not alone here — this dynamic will be difficult for many of the other companies who benefited from stay-at-home).

In the near-term, the question is likely to be whether covid created a one-time growth bump for Roblox that will reverse as alternative entertainment options open up or whether it merely accelerated already favorable secular trends.

Thoughts on long-term profitability

Roblox's financials show a business undergoing a significant margin inflection, as you might expect for a company with the topline growth profile described above. EBITDA margins are in the process of expanding, growing from ~13% in 2019 to ~25-28% in 2020. Roblox sees operational leverage across the board, with the most significant pick-up coming from 9.5 points of margin in infrastructure and customer support expenses and 5 points from R&D.

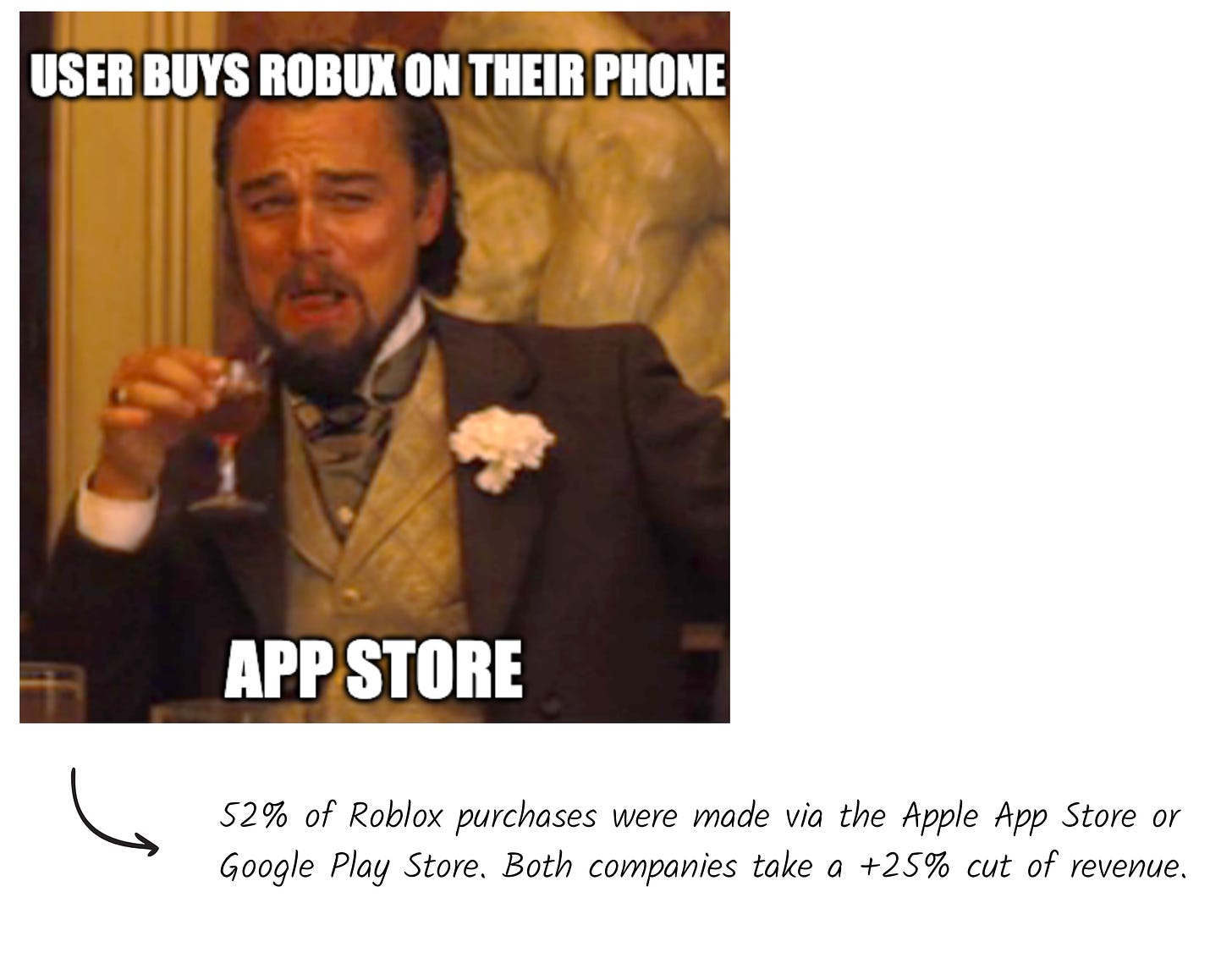

There are two line items showing margin compression, however. First, the gross margin is down by approximately 1 point YoY. This is driven by an increasing proportion of Roblox's business from mobile, where Apple or Google collects 30% of bookings. Based on the disclosure, ~52% of sales in 2020 incurred a platform fee to Apple or Google, suggesting Roblox paid in excess of $190 million to the mobile giants this year. A back-of-the-envelope calculation implies COGS for non-mobile revenue is ~13%, while fully burdened COGS for mobile revenue is ~38%.

That delta is massive. It means long-term margin impact from distribution may come down to your views on two key questions:

What percentage of the business will come from mobile vs. PC going forward?

Long-term, will Apple and Google successfully defend their 30% take rate given increasing industry and regulatory pressures?

The only other margin compressing line-item (other than stock-based comp, which we can probably ignore) was developer exchange fees, which increased from 15.8% to 16.9%. The increase is likely driven by players purchasing more content in Roblox's "Avatar Store." The Avatar Store, which primarily sells accessories to customize your in-game persona's look, was opened up to UGC creators in late-2019. Previous to this, it was populated solely by items created and sold by Roblox. This move unlocked significant demand. By mid-2020, it was reported that over 50% of purchased content in the catalog was UGC.

As alluded to earlier, it's worth asking the question as to whether developer payouts fairly compensate them for the value they are creating. Seventeen percent of sales seem like a small percentage, especially given that most of the content consumed on Roblox comes from external developers. Apple and Google, which have been under fire for their distribution take rate, only take 30%. YouTube, which similarly relies on UGC for its content, gives creators 55% of the ad revenue they generate.

Roblox advertises that it gives its developers 70% of all Robux spent on their experiences and its creators 30% of avatar accessory purchases. However, this payout is highly misleading. Payouts are made in Robux, which can be converted back into dollars at a rate of 286 Robux per dollar. Unfortunately, that rate is ~3x more expensive than the Robux retail purchase rate of 80 per dollar. As previously noted, this is because it accounts for things like the App Store tax.

User lifetimes

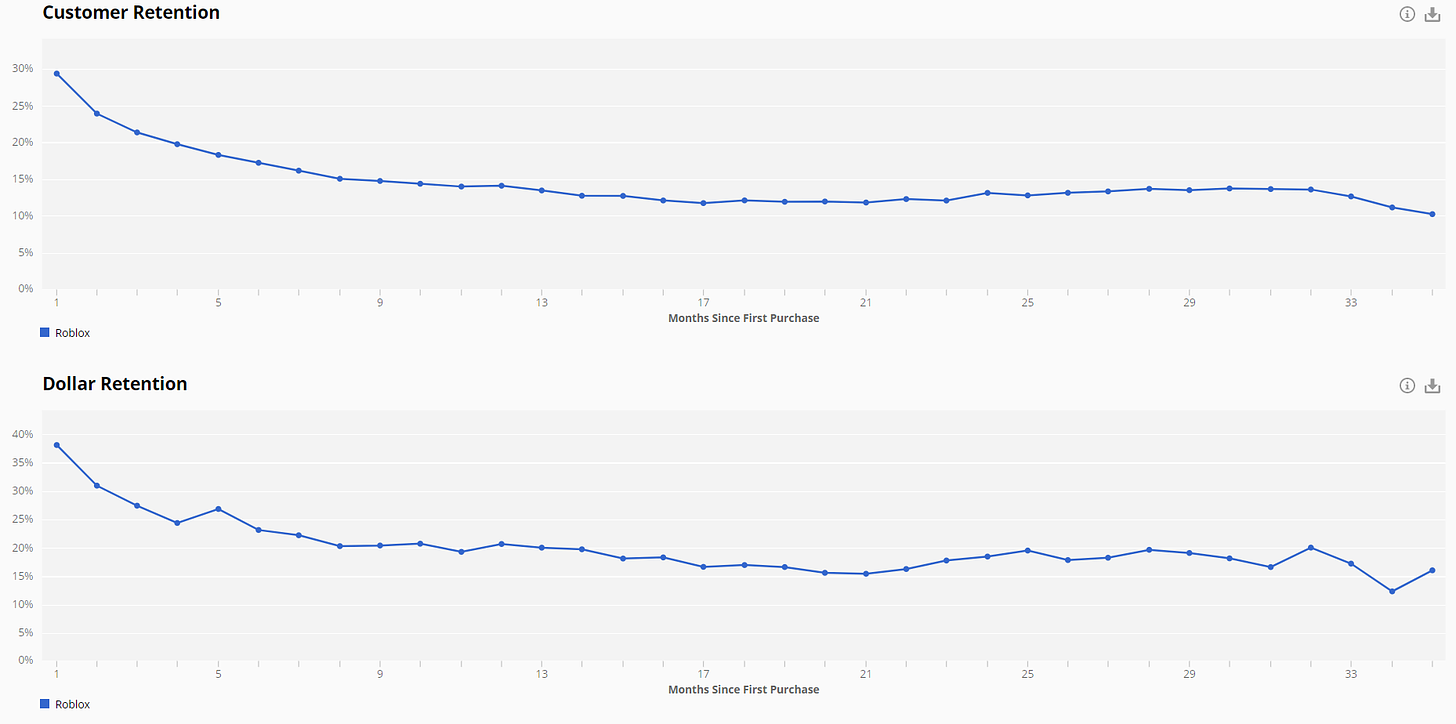

As mentioned above, and many times within the S-1, Roblox defers revenue and recognizes it over 23 months for each user cohort. Nowhere in the filing does the company provide any transparency or logic about how this figure is arrived at. Thankfully, our friends at Second Measure can clarify what the actual lifetime of an average Roblox user looks like. Interestingly, it seems to be markedly better than 23 months:

Interpreting the above, after three years, 10% of customers are still paying for a subscription or regularly buying Robux. That's a very different story than users entirely abandoning ship a full year earlier. While the reasons for Roblox's deferred revenue were covered previously, the Mystery of the 23 Month LTV remains.

Competition

The multi-functionality of Roblox's product means they compete on different fronts. Specifically, the company fights for attention with other media companies and fights for developers with other game creation platforms.

Fighting for attention

In seeking to win users' free time, Roblox does battle with entertainment behemoths like Disney, Netflix, Amazon, and YouTube. This is without mentioning social media platforms — particularly those favored by the young — like TikTok, Snapchat, and Instagram. These are especially relevant given that for many, Roblox serves as social infrastructure — the place that best facilitates hanging out and having fun online.

In gaming, Roblox competes with large studios that produce AAA polished titles and those with a more analogous model. Fortnite, owned by Epic Games, is a particular consideration here given that it marries world-building features with highly-social gameplay. Many of Roblox's games operate with fundamentally similar mechanics as Fortnite, using a battle royale structure. Minecraft, which also focuses on building but lacks Fornite's frenetic energy, is another useful comparison. Zynga, though something of a faded force, also combines gaming with a social bent.

When considering Roblox's demographic breakdown, it's hard not to see stalwarts like Nintendo as competition, too. Through Animal Crossing, the Japanese company has managed to mint a pseudo-metaverse hit with an open-world environment not dissimilar to Roblox. Unlike Roblox, Nintendo is predominantly motivated by hardware sales and, as such, has limited access to those with a console. From Roblox's vantage, that's a gift.

Fighting for developers

Unity, covered by the S-1 Club in a previous piece, presents stiff competition for game developers. As we've discussed, Roblox needs to keep talent happy so that new games are built on the platform, bringing in new users, and retaining current ones.

Roblox's advantage may be the relative simplicity of the Lua scripting language and its focus on children. The company will hope to build relationships with budding coders early on and then scale as they grow. If Roblox can add more robust functionality for super-users and provide a path toward real monetization, it may succeed in keeping developers out of the clutches of Unity. As it stands, Unity offers a more sophisticated, comprehensive platform geared toward mature developers.

Epic is another threat. Along with a handful of others, the Good Ship Sweeney is a dual-threat competitor. Epic may steal attention through Fortnite but siphons engineering talent away thanks to its Unreal Engine. Like Unity, the company's product is robust and better-suited to higher-fidelity, higher-complexity games. Intriguingly, Fortnite also has a "Creative Mode," which, as the name suggests, allows developers to create their own content. Over time, we might expect Epic to expand this product, increasing its appeal for amateur developers.

In a similar vein to Epic is Manticore. The company's last round was a $15 million injection from Epic, financing that sits on top of the +$30M brought in from VCs like Benchmark Capital. Manticore provides an ecosystem of games and a core set of casual creator-friendly tools (all running on the Unreal Engine).

The most direct competition may come from China. Reworld allows users to create games and play them with their friends. Its aesthetic is firmly focused on the juvenile market, and it's clear much inspiration was taken from Roblox.

The company has raised $56.8 million to date from investors such as Joy Capital and ZhenFund. Roblox's licenses to operate in China have arrived not a moment too soon.

Why now?

The easy answer: it is an IPO jubilee. All-time highs for the markets, software companies demanding premiums, and the public market providing a premium for all companies as investors are forced to find returns. Layer on the proliferation of SPACs and the public market seems more appetizing than ever for founders.

Looking at Roblox specifically, it is clear that 2020 was the best thing that could ever happen for the company and its gaming brethren. Gaming was up 75% over the year, with Roblox growing 171% in FY20.

As all our in-person social lives go to zero, gaming has been an oasis for free time and keeping those relationships somewhat alive. Roblox's audience, mainly younger children, have had more free time than anyone as schools are canceled, and parents need a pacifier. Roblox may be the perfect company for our current era, in more ways than one.

The Generalist’s work is provided for informational purposes only and should not be construed as legal, business, investment, or tax advice. You should always do your own research and consult advisors on these subjects. Our work may feature entities in which Generalist Capital, LLC or the author has invested.