Softbank: Twilight of an Empire

Five years after Masayoshi Son’s $100 billion fund shook the financial world, Softbank’s venture firm is crumbling. Can it be saved?

Brought to you by Fintech Nexus

London Calling! Join Fintech Nexus for its Merge conference October 17-18 at Tobacco Dock in London, and witness the impact web3 is having on financial institutions and fintechs. Hear from industry leaders and innovators as they reveal how they’re thinking about — and implementing — web3 solutions to gain a competitive edge.

In partnership with 11:FS, Merge brings together a stellar lineup including, Lawrence Wintermeyer (GBBC Digital Finance), Lex Sokolin (ConsenSys), Jess Houlgrave (checkout.com), Claire Calmejane (Société Générale), Keith Grose (Plaid), Curtis Ting (Kraken), Pavel Matveev (Wirex), Jehangir Byramji (Lloyds Banking Group), Haydn Jones (PwC), a member of Parliament, and more.

To learn more and register, visit Fintech Nexus here.

Use promo code Generalist and get 30% off!

Actionable insights

If you only have a few minutes to spare, here's what investors, operators, and founders should know about Softbank:

New terrain. Softbank has never been here before. While the Japanese conglomerate has weathered more than its fair share of ups and downs, its latest drop is of a different magnitude. Last quarter, Softbank announced a record decline of $23 billion. As one former employee remarked, “this is a proper crisis.”

A failed experiment. Much of the company’s decline can be traced back to the Vision Fund. Launched in 2017 to much fanfare, the largest venture vehicle of all time has struggled badly, performing in the bottom 10-15% of the asset class. Its second fund may fare even worse.

Organizational concerns. Founder Masayoshi Son has spoken of his desire for Softbank to thrive for 300 years. At the moment, it’s hard to imagine who might take the reins in the next five. At sixty-five years old, “Masa” cannot continue indefinitely, yet a managerial exodus has left his business short of leaders.

Cash in the bank. Despite its brutal 2022, Softbank has $35 billion in cash, with the ability to generate significantly more. Son expects semiconductor firm Arm to go public within a year, an event that should send billions back to Softbank. Though the Vision Fund’s performance suggests the firm is not a very talented investor at the moment, it does have the money to keep playing.

A history of comebacks. Masayoshi Son is not someone to bet against. After nearly going bankrupt during the dotcom crash, Son invested $20 million in Alibaba – a stake worth $50 billion at IPO. The Softbank Experience™ is never smooth, but few can recover from a loss like the company’s CEO.

Did the Romans of 460 AD smell rust in the air? Could the Ottomans, starting in the 1600s, feel a chill beginning to bristle? In other words, does a civilization notice its decline?

Perhaps it does. Those born in a dying era may develop a sense for decay.

If such a perception does exist, Masayoshi Son may be feeling it now. Five years ago, Son stunned the financial world by announcing his $100 billion Vision Fund. Bankrolled by sovereign wealth funds from Saudi Arabia and the UAE, “SVF 1” was not only the largest venture capital fund ever, it was thirty times the size of its closest contemporary. In its arrogance and imagination, it bore the signs of an august empire stepping into its power; Look on my Works, ye Mighty, and despair!

The half-decade since has revealed both the audacity and naivete of Son’s strategy. Debacles with WeWork, Uber, Oyo, Zume, and many others have left Softbank and its investors bloodied. In August of this year, Softbank announced a quarterly loss of $23 billion, the steepest drop in its history. That followed on the tail of a $17 billion decline the quarter before; in six months, $40 billion in value had evaporated. This week, news leaked that Softbank intended to cut 30% of its Vision Fund team.

History suggests that losses of this magnitude are often fatal. And yet, in Masayoshi Son, Softbank has someone with a rare gift for raging against the dying of the light. Time and again, he has shown an ability to recover from seemingly irredeemable circumstances. Though few would be foolish enough to bet against Son, saving his company’s venture practice looks like a bridge too far.

How Softbank found itself in such dire circumstances is a story that traces the arc of every great empire. It is a tale of grand ambition and outrageous wealth, kingdoms and kingmakers, conniving aides and flattering courtiers, dazzling conquests and humiliating retreats. We’ll discuss:

The rise of Masa. By the time he graduated college, Masayoshi Son was already a multimillionaire. Instead of resting on his laurels, he risked it all to build one of the world’s largest and most complicated conglomerates.

The revolution and evolution of the Vision Fund. The audacity of the Vision Fund shocked the business world and made Masayoshi Son a household name across the globe. However, deploying more than $100 billion in capital has been a challenge financially, organizationally, and culturally.

The fall of an empire (and how to save it). The Vision Fund has badly underperformed, dragging down Softbank’s finances. It has also contributed to an unproductive, short-termist culture. Masayoshi Son will need to make fundamental changes if he wants his empire to thrive after he has stepped down.

As a note, this piece draws on interviews with founders, investors, and academics. Unless explicitly noted, all contributed on the condition of anonymity.

Masa: The Making of a Legend

For those who know Masayoshi Son only from his work at the Vision Fund, his name may conjure a cartoonish figure. A small, suited businessman operating like a cross between a talking toy and ATM: he rotates through unhinged pronouncements about the future and then dispenses cash.

Such a depiction does a disservice to Son’s remarkable career. From modest beginnings, Softbank’s founder built an empire through his intelligence, grit, and insane drive.

“Look at the future”

Tosu is not known for much. Situated in southern Japan, on the island of Kyushu, its tourist attractions include a horse track, an outlet mall, and a pleasant-looking waterfall. It was also the city in which Masayoshi Son was born in 1957.

The child of second-generation Korean immigrants, Son grew up in relatively humble circumstances. His childhood home was built on land that belonged to Japan National Railways, contributing to a sense of instability throughout his early life. Son’s father supported the family by raising pigs and chickens. He also showed a willingness to take risks that his offspring would inherit, starting an illegal sake brewing business. It paid off, allowing the Sons’ to buy a car, the first in their neighborhood.

Upwards mobility came with a cost. The Sons left their Korean community for a more traditional Japanese area. A government policy forced the family to change their last name to the more native-sounding Yasumoto. A sense of alienation weighed heavily on the young Masayoshi:

I was a good student, but in those days I had a darkness in my mind all the time. It was because of my nationality. When I was with friends, I was very happy. When I came back home alone, I had the feeling that I was hiding something from my friends.

Perhaps because of this separation, Son felt driven to prove himself, to show he was not “inferior,” as he would later explain. He found an unlikely source of inspiration: the Head of McDonald’s Japan, Den Fujita.

Fujita had grown up in affluence, the child of ethnic Japanese parents. Unlike the typical executives of his era, however, Fujita was a showman with an unabashed desire to make money. He also appreciated Western products, as evidenced by an early initiative involving importing Christian Dior bags.

While Fujita built a lucrative import business, winning the McDonald’s rights in 1971 represented a different magnitude of opportunity. Not all saw it that way, however. Traditionally, Japanese consumers had little interest in either beef or potatoes, an absence Fujita believed contributed to national frailty. “The Japanese are very hard-working, but very weak, very small, and our faces are so pale,” Mr. Fujita once explained, “I thought we had to strengthen ourselves. That's when I thought of beef.” Whatever one thinks of his tortuous rationale, Fujita’s bet paid off with the franchise expanding rapidly.

Shortly after kickstarting his McDonald’s empire, Fujita gained even broader recognition. In 1972, he published the first of eight business books, “The Jewish Way of Doing Business.” To the modern ear, this sounds like a disquieting title. However, as Fujita later explained to the New York Times in 1992, the work was intended to celebrate Jewish entrepreneurship and business savvy, though it involved significant stereotyping. "Please don't misunderstand," Fujita said. "I'm trying to do something good for the Jewish people.” At the time of publication, Fujita’s topic was also not unusual, with many Japanese authors using the Jewish people as an inspiration and lens through which to assess their own country.

The book proved a smashing success, selling 200,000 copies in its first month and eventually surpassing more than a million. It made its way into the hands of a sixteen-year-old Masayoshi Son. In Fujita’s words, he discovered a boldness and originality that he hadn’t found elsewhere. “I was so impressed,” Son recalled. “The guy who wrote this must be great,” he thought.

What followed next was classic Masa. Indeed, it may be the first example of what would later become Son’s zone of genius: the impossible, inescapable sell.

Convinced that Fujita would provide wisdom he couldn’t attain elsewhere, Son began calling the magnate’s offices. When he reached Fujita’s assistant, he passed on a message: he was a student, an ardent admirer of Fujita, and he wanted to meet. Unsurprisingly, Son was batted away, but he remained undeterred. Over the following months, he called Fujita’s offices sixty times by his estimation. When assistants told him Fujita was a busy man and unlikely to make time for a student, Son remembered instructing: “Don’t decide by yourself. Let him decide.”

Son’s relentlessness wasn’t cheap. Calling Tokyo from Tosu incurred significant telephone charges. Still, Son wasn’t about to give up. In a maneuver repeated throughout his life, Son saw a seemingly insurmountable problem and doubled down rather than backing off. After hopping on a flight to the Japanese capital, he called Fujita’s office again.

He told the assistant that he had flown to see Fujita and gave her a message to pass on. “Tell him this exactly the way I say it,” Son instructed. “You don’t have to look at me. You don’t have to talk to me. You can keep on walking. I just want to see his face for three minutes.”

In the end, Fujita gave Son fifteen minutes – more than enough for the young man to ask the question he’d been holding inside: “What business should I do?”

Fujita pondered, then replied. “Computers. Don’t look at the past industries,” he said. “Look at the future.”

“What is the most efficient use of my time?”

To build the future, Son would have to break from his past. The same year he met Fujita, Son informed his parents of his desire to move to the United States and continue his studies. They assented, though not without their reservations. Bidding his family goodbye at the airport, his mother broke into tears, fearing he would never return to Japan. “Don’t cry, Mom,” he said. “After I graduate from school, I’ll come back. I promise.”

After he’d landed in California, it didn’t take long for Masa to demonstrate his talents. Within a week of arriving at San Mateo’s Serramonte High School as a sophomore, he was bumped up a grade, becoming a junior. A few days after that, he was promoted to a senior. His senior year lasted four days before he took an exam and graduated. Hopefully, he was able to attend a three-minute prom at some point.

Son matriculated to Holy Names College, spending two years at the Oakland university before transferring to the University of California, Berkeley. Though Son took his economics degree seriously, he set another goal: to earn $10,000 a month from only five minutes of work per day. When he asked a few college classmates if they knew of any jobs with such characteristics, they quite reasonably dismissed him as crazy. So Son began to ask himself: “What is the best, most efficient use of my time?”

He settled on invention. After all, a single clever design could yield thousands in profits, if not more. Son decided to try, setting a five-minute timer and imploring himself to think. “Invention, come!” he implored.

Remarkably, it worked. After outlining 250 concepts in his “Invention Idea Notes,” Son settled on creating an electronic dictionary, hiring professors to help build it. He sold it to Sharp for $1.7 million. Next, he decided to import Japanese video games, earning another $1.5 million. Within 18 months, he’d made $3.2 million. “That is better than $10,000 per month,” he said wryly.

Could this story be literally true? Could Masayoshi really have achieved such outcomes on just five minutes of work a day, a smidge more than fifteen hours total? We must allow every mythology a little dramatic license.

Despite prospering in America, after graduating from Berkeley, Son fulfilled his promise to his mother. He was headed back to Japan.

“I have no evidence, but I strongly believe in myself”

Son returned to a Japan still partway through its postwar economic “miracle.” In 1981, the same year of Masa’s homecoming, management guru Peter Drucker outlined the complexity and intelligence at the heart of the country’s growing commercial strength, an aptitude shortened to “Japan Inc.”

For a man that moved at superhuman speed in America, Son’s Japanese commercial efforts started more slowly. Looking for a business that would occupy him for the “next fifty years,” Son methodically worked his way through different ideas, from writing software to launching a chain of hospitals. Once he had enough options, Son compared them to each other in a massive matrix that rated the ideas on four dimensions:

How likely Son would fall (and stay) in love with the business.

How unique the business was.

How likely it was that the business could become number one in Japan in ten years.

How much growth there was in the business’s industry.

“I picked the best one,” Son said. “The personal computer software business. That was the start of Softbank.” More specifically, Son landed on a plan to serve as a broker between hardware suppliers and small software creators. His business would connect the long tail of software companies desperate for distribution to physical stores that sold PCs and electronics. “It was like a bank,” Son said, “It was a software bank.” The name wrote itself; Son called his business Softbank.

Looking to make a big splash, Son paid for the largest booth available at an upcoming consumer electronics show. Rather than promote his services, he called local software companies and offered to show off their products for free. He hoped that by demonstrating the range of products available, Softbank could begin striking wholesale deals with stores.

It proved an expensive failure. Though crowds flocked to Softbank’s table, it produced little business. Those interested in buying software simply shared their information with suppliers directly. “I was cut out of the deal completely,” Son recalled, “I probably made back one-twentieth of the cost of the booth.”

For a few weeks, Son endured humiliation from his chosen industry. “Many people were laughing at me,” Son remembered, “They said, ‘that guy’s really dumb. He’s a nice guy, but dumb.’” It didn’t take long for his fortunes to turn around, though. One of Japan’s largest PC dealers, Joshin Denki had gotten word of Softbank’s booth and was interested in discussing a partnership. During a meeting in Tokyo, Joshin Denki’s president grilled the young upstart: “He asked me many questions: ‘How much capital do you have? How old are you? What kind of business experience do you have?’”

Son’s memory of his response offers a glimpse into the Softbank founder’s persuasive power. It deserves to be read in full:

I told him, I have very little money, very little business experience. I have no product, nothing. What I do have is the greatest enthusiasm, the greatest desire to succeed. You have already been purchasing some PC software. Today you probably have more knowledge and more experience at this than I do. You are older than I am and more talented. But in addition to purchasing PC software and hardware, you are also going to purchase home electronics products, refrigerators, televisions, VCRs. I will dedicate all my time and effort, all my energy, my entire spirit to PC software only. Several months from now, who do you think will be more knowledgeable, more of a specialist in this business? If you want to be the number one PC dealer in Japan, you have to find the number one guy in software distribution. That’s me. I have no evidence, but I strongly believe in myself.

Softbank got the contract. And thanks to the social validation Joshin Denki supplied, many others followed. Softbank went from annualized revenue of $120,000 to $27.6 million within a year.

“Somehow, I survived”

Softbank scaled through the 1980s and early 1990s, becoming Japan’s number one software distributor and a publisher of technology magazines. In addition to increasing interest in Softbank’s industry, publications like Oh!PC and Oh!MZ advertised the company’s products.

In 1994, Softbank went public, raising $140 million. Masayoshi Son seemed to use the company’s new status as a catalyst for reinvention, conducting a series of acquisitions, including computer publisher Ziff-Davis for $3.1 billion.

Beyond bulking up his existing business units with buyouts, beginning in 1995, Son started making minority investments in promising companies. He was particularly enamored with those that leveraged technology’s latest craze: the internet. Son formed Softbank Technology Ventures (SBTV) to capitalize on the opportunity.

Son’s publishing experience helped him identify SBTV’s first target. Yahoo was just a year old when Masa approached it. Though Jerry Yang’s business was still in its infancy, Son and his team saw its potential as a modern-day publishing giant, but with significantly lower costs.

SBTV invested $2 million in late 1995; four months later, Masa was back with a much more audacious offer. Over cold pizza, Softbank’s leader pitched Yang on accepting a $105 million investment in exchange for a 33% share. “Most of us thought he was crazy,” Yang recalled. He took the madman’s money all the same.

It didn’t take long for the bet to pay off. Yahoo went public two months later and in the years that followed, Softbank invested another $250 million into the company. Three years later, SBTV’s stake was valued at $8.6 billion, even after selling shares worth $450 million.

That wasn’t the only way Son and Yang partnered. In 1996, Yahoo and Softbank unveiled a joint venture: Yahoo Japan. Son’s business put up $1.2 million for 60% of the entity, with Yahoo contributing $800,000. In the years that followed, Yahoo Japan would grow to become one of the country’s largest websites. By 1999, it was the starting portal for 80% of Japan’s internet users, valued at $4.5 billion.

Masayoshi continued his shopping spree throughout the mid-to-late 1990s, racking up shares in a staggering 800 startups including E-Trade, ZDNet, Webvan, and Geocities. A sign of things to come, Son occasionally wrote massive investments off minimal research. A single call with E-Trade’s founder was sufficient to deploy $400 million in funding.

As tech mania took hold, Softbank’s “netbasu” – a portmanteau of “internet” and “zaibatsu,” the Japanese term for integrated conglomerates – made Son the richest man in the world, if only briefly. “For three days, I became richer than Bill Gates,” Son said of a period in 1999. “My personal net worth was increasing by $10 billion per week.” By early 2000, Softbank was valued at $160 billion.

Then, it all fell apart. Later that year, the dotcom bubble burst and, with it, the value of Softbank’s holdings. Within six months of being the wealthiest man on earth, shares in Son’s company had declined 99%.

Over the course of a year, Son lost an estimated $70 billion in net worth, a drop that has been called “The greatest loss that any human being has ever suffered, financially.”

“We almost went bankrupt,” Son said. “Somehow, I survived.”

“Believe me, and lend me money”

In interviews, Son comes across as an avuncular character, chuckling at his ambition, open with his mistakes. Sure, there is bluster and plenty of theatrical flair; but listen to him tell a story, and it becomes obvious why he is considered such a convincing salesman.

Behind the scenes, Son is a much more ruthless presence. Though he can charm and wow with soliloquies about the future, one source with deep knowledge of Softbank and its founder notes Masa’s eerie indifference to others. “He doesn’t regard other people as important,” the source said. “They’re tools to him, instruments designed to serve his greatness. He’s pretty sociopathic.”

This weakness has caused Son countless cultural and organizational challenges, which we will discuss in detail. In some instances, it has proved valuable. Son’s detachment gives him the rare ability to leave mistakes behind him. “He is very good at ignoring the past and moving forward,” the same source said, comparing the Softbank founder to Roger Federer. Just as the Swiss tennis maestro can brush off a bad point to win the next, Son sheds defeat swiftly. “He can move on from one thing to the next, pathologically.”

Nothing captures this quality quite like Masa’s millennial year. In 2000, Son lost more money than any human in history. He also made his best-ever investment: Alibaba.

As with so many of Son’s decisions, his conviction relied on almost numinous intuition rather than rigorous analysis. “He had no business plan and zero revenue,” Son said of Alibaba’s green CEO Jack Ma, “But his eyes were very strong. Strong eyes, shining eyes.” Though Son felt Alibaba’s business model was wrong, he believed in the young leader, perceiving him to be an impressive motivator.

Softbank invested $20 million. When Alibaba went public in 2014, Softbank’s stake was valued at $60 billion, a 300,000% return. In 2020, Son’s holding was pegged at $150 billion. It is considered one of the greatest investments of all time. Coupled with Son’s Yahoo bonanza, it places the Softbank investor in elite company. “People celebrate John Doerr for getting Google and Amazon,” a source mentioned. “This is as good as that.”

However, it would take time for Alibaba to contribute to Softbank’s financial health. In the interim, Son set about reinventing his business to focus on the nascent mobile internet movement. First, Son sought to get in on the action by trying to get a license for mobile spectrum. The Japanese government turned him down, telling him there was no space left. A year-long skirmish commenced, with Softbank suing the government for access to bandwidth. Eventually, Son won out, gaining access to newly allocated frequencies in 2005.

To truly compete in a cutthroat telecommunications industry, Softbank needed more than spectrum. Son saw an opportunity to accelerate his initiative through an acquisition. Vodafone had entered Japan several years earlier but failed to make an impact. With pressure mounting on CEO Arun Sarin to curtail the troubled initiative, its regional assets were suddenly in play. There was one problem: Softbank had $2 billion in capital, but Vodafone’s price was a purported $20 billion. “I was $18 billion short,” Son said.

Masa went hat in hand to a bank to make up the difference. Echoing his conversation with Joshin Denki’s president twenty-five years earlier, Son had to convince his counterparty of his suitability. He outlined his plans to reinvigorate the project and turn it into a cash-generating machine. “Believe me, and lend me money,” Son said, summarizing his argument.

Son secured Vodafone Japan for less than he’d expected, $15 billion. Though the market didn’t know it yet, Son had big plans for his mobile unit. Masa had visited Steve Jobs a year earlier, bringing a “little drawing of an iPod with mobile capability.”

“Don’t give me your shitty drawing,” Jobs told Son, “I have my own.” When Son asked if his company could serve as the official carrier for Jobs’ forthcoming creation, Jobs agreed. “You’re crazy,” the Apple chief said, “We haven’t talked to anybody, but you came to see me first. I’ll give it to you.”

In 2008, Softbank Mobile and Apple announced their partnership. If you wanted an iPhone in Japan, you had to join Son’s network. Softbank Mobile soared, reaching 25 million users by 2011. Masayoshi Son may have started the decade down and out; he entered the next reestablished as a tech titan.

Vision: Softbank’s Venture Evolution

The making of Masayoshi Son is fodder for a feel-good movie. But the story of the Vision Fund is the richer text. In its hubris and excess, skullduggery and sycophancy, it is a tale with the vividness of a Shakespearean drama. Across four acts, we’ll chart the vision and blindness of Softbank’s investing.

Act 1: The Prince

Nikesh Arora was the solution. For decades, commentators and shareholders had bemoaned one aspect of Masayoshi Son’s empire: its reliance on him. Despite scaling to a market cap of more than $70 billion by 2014, the mega-conglomerate still bore the markings of a one-man show. One former board member distilled the company’s essence: “It’s Masa, Masa, Masa.”

Though Son spoke publicly about building a business that would last three centuries or more, he had largely failed to cultivate a management team that could outlast him. Softbank might be a behemoth, but it was one with a single point of failure. As Son approached his sixtieth birthday, this lack of resiliency was increasingly troubling.

Then along came Arora. Hired in 2014 as the head of Softbank’s investing efforts, the former Google executive was quickly promoted to President and COO status, with Masayoshi Son publicly calling him his successor. “Masa said it explicitly,” a source noted. “He had never said that before and hasn’t said it since.”

In many respects, Arora was an unusual choice as Softbank’s CEO-in-waiting. He hadn’t built a company himself, rising through the ranks at Putnam Investments and Fidelity. On the Masayoshi Sociopathy Index, founders occasionally merited some respect, but financial types and company men were especially pointless. Son was known to sneer, “you’re just a banker,” at an overstepping underling.

Nikesh Arora was no ordinary banker, nor was he a typical executive. In 2004, he took the reigns as VP of Operations at Google Europe. Within five years, he’d driven revenue from $800 million to $8 billion. As significantly, he’d helped federate the company, decentralizing power from its California hub. Eric Schmidt, then CEO of the search giant, referred to Arora as “the finest analytical businessman I’ve ever worked with.” Always a keen assessor of softer skills, Son will also have taken note of Arora’s intensity and charisma.

It didn’t hurt that Arora hailed from India. After watching Alibaba take flight over the past fourteen years, Son had started looking for his next mega-hit. He became convinced that it would come from Arora’s homeland. “He saw India as the next China,” a source explained. “He planned to run the same playbook, find the next Alibaba. For a lot of reasons, it didn’t work out that way.”

For a brief period, Son and Arora seemed like a perfect match. By late 2015, Son waxed lyrical about his protege. He talked up the relief of finding a successor and the value of having a true thought partner. “Since he joined, I can have a high-level discussion for every angle around the future,” Son said, damning long-serving lieutenants in the process.

Arora’s words around the same time would have been music to Softbank’s investors’ ears. “[Son] has never had a problem taking big bets,” Arora explained in one interview, “What we have to do now is take that genius and figure out a way to at least institutionalize some of his values, so the future generation of SoftBank can actually execute in the same way that he does.” Arora recognized Son’s greatest weakness and seemed equipped to address it head-on.

The newcomer’s impact went beyond well-chosen words and winning Masa’s favor. As chief of Softbank’s investments, he shuttered the company’s existing venture vehicles, most of which were operating on a trivial scale. That included minor funds in New York and Seoul. “None of them moved the needle,” a source said. “Nikesh came in with a machete and cut it all.”

In its place, Arora consolidated a team of ten or so in San Carlos, California. Instead of haphazardly chasing deals across stages, Arora set his team the task of finding the best growth investments around the world. In 2014, this represented a relatively unusual focus. Beyond Tiger Global, DST, and Coatue, few institutions were chasing the segment. “Growth investing wasn’t a mainstream concept at that point,” a source noted.

Though not as frenzied as Softbank’s later years, Arora’s team moved aggressively in pursuit of that goal. Investors “hopped around the world” in search of the next winner, backing Snapdeal, Ola, and Oyo in India; Didi Kuadi in China; Coupang in Korea; Grab in Singapore; and SoFi in the U.S. Though Softbank showed flexibility around valuation, it wasn’t the pushover it became in later years. For example, in 2015, Arora passed on backing Snap at a $16 billion valuation, believing that even doubling his money would prove difficult. (He was proven right; the company’s valuation at IPO was $24 billion.)

All seemed to be working smoothly, yet by mid-2016, Arora had gone. The stated reason for his departure was a matter of timing. Initially, Arora had expected Son to step down in 2016, when he turned sixty. In discussions leading up to Softbank’s annual general meeting, Son told his deputy that he’d changed his mind and intended to remain CEO for another five to ten years. Without a clear path to take over, Arora decided to leave.

Listen to whispers, and you’ll hear that an insider stoked the friction between Son and Arora. The same year Arora arrived at Softbank, the company hired Deutsche Bank executive Rajeev Misra. Like Arora, he was appointed to help with the firm’s investments, though in a more minor role. “He wasn’t central,” a source said of Misra. “He was in the wings.”

If a 2020 Wall Street Journal report is to be believed, Misra found this state of affairs unsatisfactory. He reportedly commenced a prolonged smear campaign against Arora to clear his leadership pathway. Through paid intermediaries, Misra is believed to have fed negative stories to the press and fabricated open letters to shareholders calling for an investigation into Arora’s financials. Misra even attempted to catch Arora in a “honey trap,” according to the report. Beautiful women stationed at a Tokyo hotel were tasked with enticing Arora to a bedroom equipped with cameras. The maneuver failed. But the sustained pressure on Arora may have contributed to his departure and impacted his relationship with Son.

Misra denied the scheme. “It was never proven,” a source said, “but when people heard about it internally, they thought it was plausible.” Perhaps Softbank’s prince was undone by a Machiavellian masterclass.

The most fundamental reason for Arora’s split with the company may be Son’s fickleness. Though broadly detached from others, Son occasionally takes a shine to someone, though only for a brief period. Flavors of the month come and go; favored one minute, frozen out the next. This goes for both employees and the founders of portfolio companies. A source highlighted Ritesh Agarwal, CEO of Oyo, as one who had received this treatment. Agarwal was just twenty-one when Softbank invested in his hotel chain. “He was this young kid, and he idolized Masa,” they said. “Then, one day, he got dropped.” The same person suspected Arora had gone through something similar. “It’s like the story of Icarus. These people fly closer and closer to Masa, closer to the sun. At some point, they catch fire and fall to the ground. But the sun is still shining.”

Act 2: The Mad King

With Arora gone, Misra stepped into the limelight. Unlike his predecessor, Misra seemed more interested in growing Softbank’s scale than maintaining a disciplined strategy. “Rajeev moved into center stage and effectively said to Masa, ‘I can get you a lot of money.’” He came good on that promise, though not without a healthy dose of Masa magic.

In 2016, the Softbank CEO headed to Saudi Arabia for a meeting with Mohammed bin Salman (MBS). The country’s future Crown Prince and prime minister then served as the head of the Public Investment Fund (PIF), Saudi’s sovereign wealth vehicle. It is worth questioning the morality of this expedition from the outset. Though many hoped MBS would be a reformer at the time, he nevertheless managed the money of a country that is a persistent human rights abuser. Since becoming Saudi ruler, MBS may have courted Western power centers from Silicon Valley to Hollywood, but he has demonstrated his brutality, notably ordering the torture and murder of journalist Jamal Khashoggi in 2018.

If Son had any moral objection to the expedition, he does not seem to have shown it. As the story goes, he was reviewing the Vision Fund’s deck on the flight over when he reached the page outlining the target fund size. He and Misra had decided on $30 billion, a whopping sum. But in a characteristic fit of ambition, Son crossed the number out and replaced it with $100 billion. “Life is too short to think small,” he said to an aide.

It proved an inspired decision. “The reason that was genius was that it took the conversation from, ‘Hey PIF do you want to allocate capital to our fund?’ to ‘Hey MBS, do you want to transform your country?’”

In a forty-five-minute pitch, Son outlined his vision for the Saudi leader. At the heart of his argument was a belief in “the singularity,” a hypothetical future moment in which technological progress explodes and artificial intelligence surpasses human intellect. The internet and mobile internet supercycles had produced big winners for Softbank, but Son explained that AI and the singularity presented an even larger opportunity. MBS was convinced, agreeing to anchor “SVF 1” with $45 billion. “One billion per minute,” Son gleefully recounted.

Other investors followed suit, including Apple and Mubadala, a fund owned by the Emirati state, taking Son to a hair below his $100 billion target. “With that capital base, Masa was on top of the world,” one person said.

While raising such a ludicrous sum had proven surprisingly easy, managing it was another matter. Deploying $100 billion required different skills and a much larger team. “You went from a craft business to an industrial machine,” one person said, “The old team had built an investing culture, but suddenly it went from ten people to a hundred, to several hundred.”

Softbank’s hiring spree mirrored its subsequent investing strategy. Son and Misra showed little discipline on compensation nor much discernment for their recruits' experience. “They staffed the organization with people that had never invested. They were paid whatever it took to get them in,” a source remarked, “Nothing about the fund’s carry was determined for years.”

Such fuzziness did not stop the Vision Fund’s growing army from sourcing investments. “It became like a sales organization: go everywhere, get everything,” a source said. As politics crept in, fiefdoms emerged, each fighting for influence and scope. But while hundreds were involved in finding potential deals, there was only one decision maker. “Masa was the ultimate filter,” a source said.

In theory, this practice might have worked. After all, Son had a consummate slugger’s track record, whiffing plenty but hitting big when it mattered. With deep access to the world’s most exciting startups, vetted by his team, how many winners might he find?

In practice, the Vision Fund’s internal processes degraded quickly. “The game became, ‘how do you pitch something to Masa so that he invests in it?’” a source said. A feeling that Softbank had abundant, neverending access to capital also damaged selection since no one ever felt like they needed to choose one investment over another. “It was a far cry from thoughtfully considering investment opportunities, with the assumption of scarce capital,” someone noted.

The results of this process were uninspiring. “You get things like Zume Pizza, which is just a pizza truck,” a long-time investor said. “That got pitched as a revolution, the future of food.” Softbank invested $375 million.

“You also get things like Brandless. A physical products company that just said, ‘Let’s do all the products at once, with no product-market fit. Let’s go and do all the things,’” they added. “Both of them failed dramatically because they broke the cardinal rule of Silicon Valley, which is that you get to product-market fit first and then you do more and more.” Softbank invested $240 million.

Beyond a process that encouraged intellectual dishonesty, the Vision Fund fell prey to Masa’s predilections. Though gut instinct had been good enough to identify the early talents of Jerry Yang and Jack Ma, it proved an insufficient filter for growth stage investments. “Masa is an amazing early-stage investor,” one VC remarked, “but for growth, you have to turn on the analytical mind a lot more. You have to thoughtfully size the market.” While Son’s team supplied additional analysis, it became increasingly warped by their leader’s obsession with ludicrously ambitious forecasts, rendering them effectively useless. Consequently, plenty of mega-deals were done on the back of the same hunches that had guided Son’s seed investments. “If a convincing entrepreneur walked into the room, it was almost guaranteed they would get hundreds of millions of dollars,” a former employee said.

Softbank’s unstructured processes led to a muddled portfolio. Initially, the Vision Fund’s strategy showed a certain shrewdness. Beyond an interest in artificial intelligence and the singularity, the vehicle intended to pick market leaders and give them the capital they needed to dominate rivals and execute valuable long-term initiatives. “There’s a lot of intelligence behind the model. The thinking and philosophy behind it were not decrepit, even if the execution wasn’t thought through,” one portfolio founder remarked. “Overcapitalizing the winner is the only legal way to establish a monopoly.”

It rarely panned out that way. Though Son occasionally commanded his team to “get me AI companies,” the deals that Softbank ended up doing often occupied the world of atoms rather than bits. Massive bets like WeWork, Uber, Oyo, Didi, and Wag all fell into this category.

While some companies may have benefited from the cheap capital, others struggled beneath its burden. When CEOs can no longer find productive ways to deploy funding, they may eventually turn to unproductive ones – especially when beneath the watchful eye of a ferociously impatient investor. Over-hiring and ballooning marketing costs were commonplace.

Eventually, some within Softbank started to question its strategy. Could the firm really generate a return on $100 billion? Especially like this? One person at the company during that period outlined the mental math with which they wrestled:

Assume Softbank owns an average of 20% in each of its companies. Just to make its money back, the entirety of its portfolio would need to be worth $500 billion. Getting to a 3x return – presumably, SVF 1’s baseline target, would mean a total portfolio value of $1.5 trillion. Was it even possible for the market to create that much net-new value in seven years?

Perhaps recognizing the daunting task before them, and exhausted by office politics, many of the Vision Fund’s recruits left after two years. “You had a bunch of attrition,” one source said. Those that stayed and dared to ask how Softbank could defy financial physics were fed the same response. “The message from on high was always the same: you’re thinking too small, you’re thinking too small, you’re thinking too small. The whole world is going to change.”

Act 3: A Humbled Court

Beginning in 2019, Softbank started taking a different tact. Though by any normal standard, it still operated at full speed, some prudence began to enter its processes.

In March of that year, Softbank announced a $5 billion Latin American vehicle named the “Innovation Fund.” Headed by Marcelo Claure, the former CEO of Sprint, the division was tasked with finding winners in the emerging market. It represented a massive moment for the region’s tech ecosystem. “Softbank’s brand when they started in Latin America was Andreessen Horowitz times three,” one founder said of the firm’s entrance.

Notably, the Latin America team seems to have worked separately from the rest of the Vision Fund. “It was a completely independent operating unit,” the same founder remarked. Perhaps because of that, this team doesn’t seem to have the same reputation for profligacy the mothership does in other markets. Indeed, its name carries weight for entrepreneurs, smoothing recruiting and partnerships. “Having Softbank onboard gave us social validation for mid-market enterprise sales,” one person reported. Softbank would later re-up the Latin American team with a further $3 billion. The group invested in companies like Nubank, Rappi, Kavak, Ualá, and Kushki. Recently, Softbank announced the Latin America fund would bifurcate. The later-stage team rejoined the core Vision Fund segment while its early-stage team was spun out into a fund called Upload Ventures.

Softbank’s second Vision Fund also demonstrated a little more sanity. A few months after launching the Latin American initiative, Son’s team announced its next venture iteration. Unlike the previous fund, SVF 2 had no outside limited partners; the entire $56 billion came off Softbank’s balance sheet. This was perhaps partially driven by a desire to distance the fund from PIF after Khashoggi’s murder and a sign that other limited partners had been less than convinced by its 2017 vintage.

“The biggest change in Fund 2 is not to be concentrated,” managing partner Navneet Govil said. “The differences are that we’re doing a lot smaller ticket sizes. It’s not the large multi-billion dollar ticket size.” Softbank seemed to have realized that many companies had an upper limit on the capital they could productivity digest.

While this shift suggests Softbank had learned some modesty, it did not escape 2019 without further humbling. WeWork filed for an IPO that August, setting off the chain of events that put SVF 1’s manic style of investing in sharp relief. No, WeWork was not worth $47 billion. No, it was not even worth $20 billion. The following months saw the co-working space spiral, with Adam Neumann departing and Marcelo Claure stepping in as interim chief. The $10 billion Masa had invested in the company seemed to be going up in flames.

In May 2020, Softbank reported its annual returns for its past fiscal year. For fifteen years, Softbank had posted profits. The year before, the company had boasted $19.6 in gains. This time was different: Softbank's losses reached $12.7 billion. The Vision Fund was the clear drag, posting a loss in value of $17.7 billion.

Three years earlier, Masayoshi Son had stood atop the largest pile of money a venture capitalist had ever assembled. Now, he was buried beneath it.

Act 4: The Return

To make sense of the period between 2020 and 2022, you must first know the Law of Softbank. Here it is: when you think you know which direction it is heading, it changes. Around the time Son shared his company’s staggering losses, the tech markets began to change, embarking on a dizzying bull run that only ended this year.

“The world turned in 2020,” an investor said. “It started to look like Masa had been right: the future would be unconstrained, and everything was going to change faster than we thought.” Whatever caution Softbank developed between 2019 and 2020 was swiftly thrown to the wind. Son’s vision had been vindicated; now, it was time to attack.

A new competitive dynamic spurred Softbank’s resurgence. Tiger Global had once invested selectively and surreptitiously, but especially in 2021, the firm began deploying with a fervor that rivaled and perhaps even surpassed Son’s shop. “Out of all the 2021 drunk investors, I put Tiger way, way above Softbank,” one founder said. Their aggression prompted Masa to wonder whether the Vision Fund should emulate the crossover’s strategy, outsourcing its diligence process.

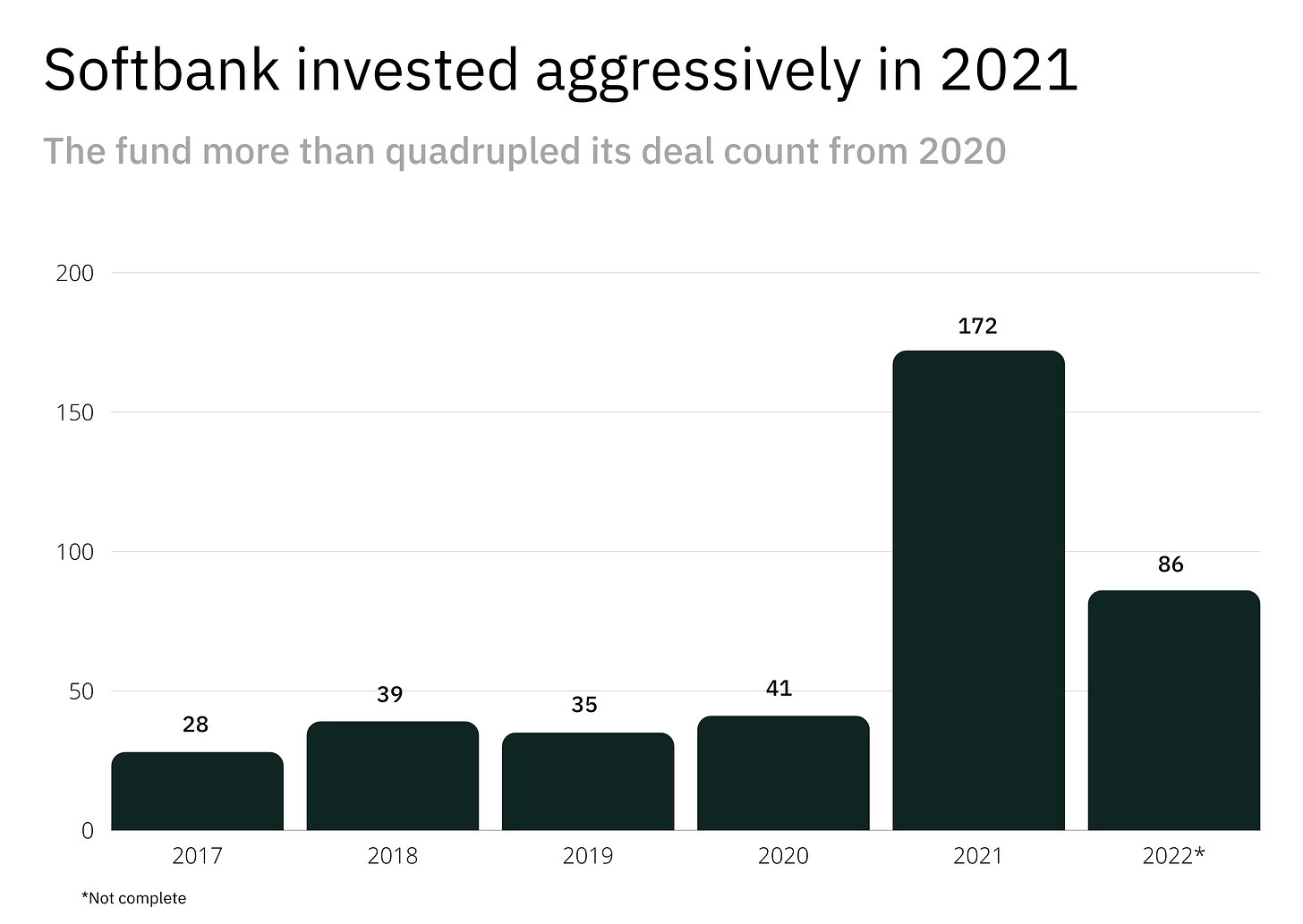

In the end, Softbank went for a simpler solution, running the clock back to its 2017 playbook. “Last year was even more aggressive across the board,” a team member said, “It was the ultimate culmination of the Vision Fund idea.” Over 2021, the Vision Fund made 172 investments, according to Crunchbase. For comparison, between 2017 and 2020, it made just 143. This doesn’t include investments made by the Latin American fund. Softbank’s shopping spree involved taking stakes in FTX, Chime, Meesho, ConsenSys, Remote, Cerebral, and many others.

Son did show some signs of learning from his previous mistakes, though they were modest. “Masa realized he was being pitched rosy stories,” one source said, “So for the past couple of years, he would have the Japan group double-check other teams’ work. Before that, there was no uniform, systematic process.” While an admission that his employees’ analysis could not be trusted, it at least provided further rigor.

In May 2021, a year after its record losses, Softbank reported all-time high profits of $45.8 billion, helped by surging IPOs for Coupang and DoorDash. Son was ebullient, referring to Softbank as a "factory of golden eggs.” If any doubt had ever entered Masa’s mind, it had certainly evaporated. “There were many investment failures, such as WeWork, Greensill and Katerra," Son remarked. "But what I regret more is the missed opportunities to invest."

The Law of Softbank meant there was only one direction for the company to go. The markets of 2020 and 2021 might have giveth, but 2022’s taketh away. Ongoing disruptions from the pandemic and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine have contributed to a downturn that has particularly affected high-growth tech companies. While that’s impacted portfolios across the board, it hit hyperactive players like Tiger Global and Softbank especially hard. Both deployed billions at the top of the 2021 market. As conditions have changed, many holdings are now underwater.

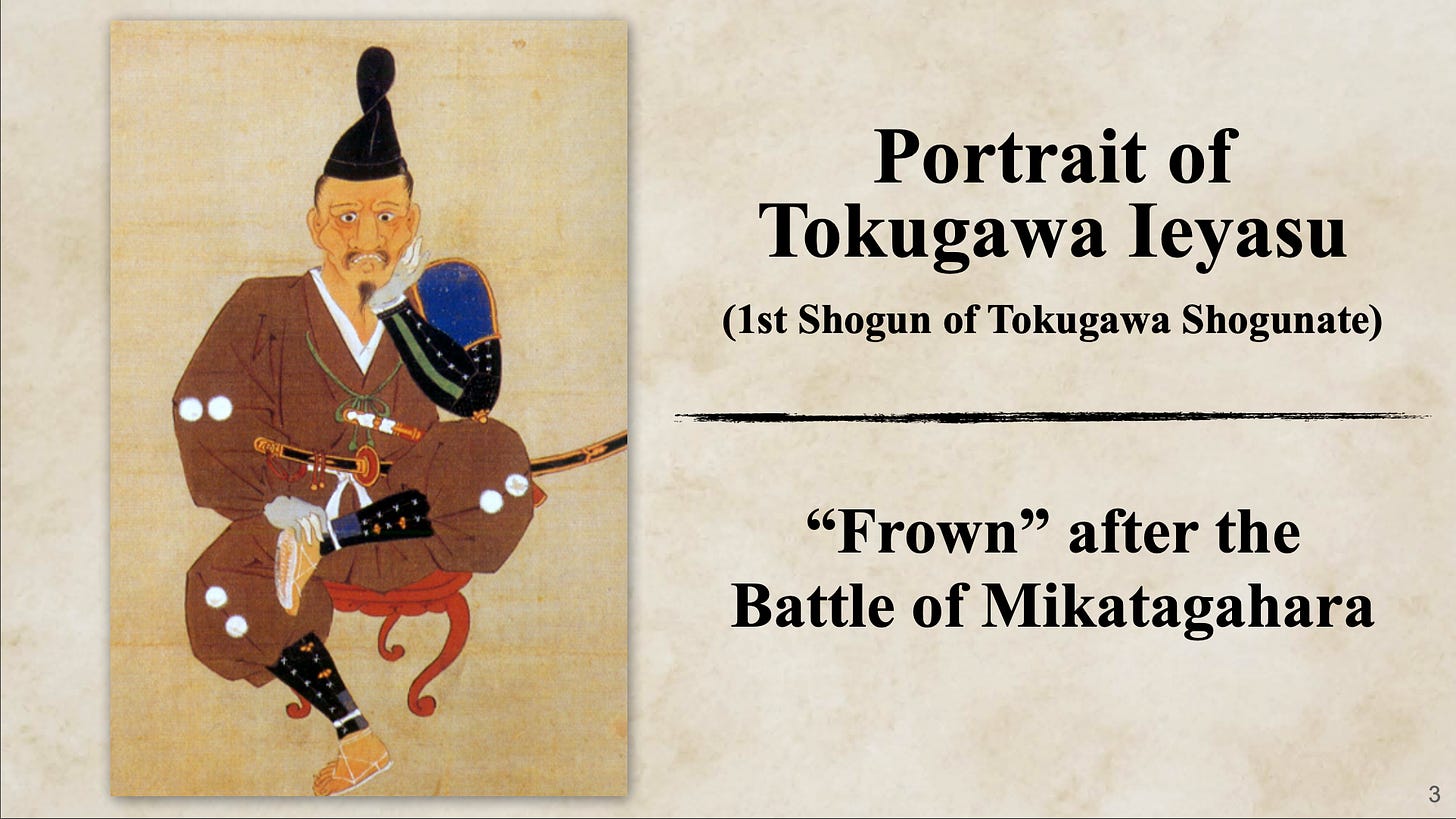

Masa completed a parabolic triptych of annual general meetings this past May. In front of a picture of a defeated 16th-century Japanese general, Tokugawa Ieyasu, Son announced a quarterly loss of $23 billion, a new record. “When we were turning out big profits, I became somewhat delirious, and looking back at myself now, I am quite embarrassed and remorseful,” Son said. As he had in 2019, Softbank’s supremo promised “heightened investment discipline” going forward.

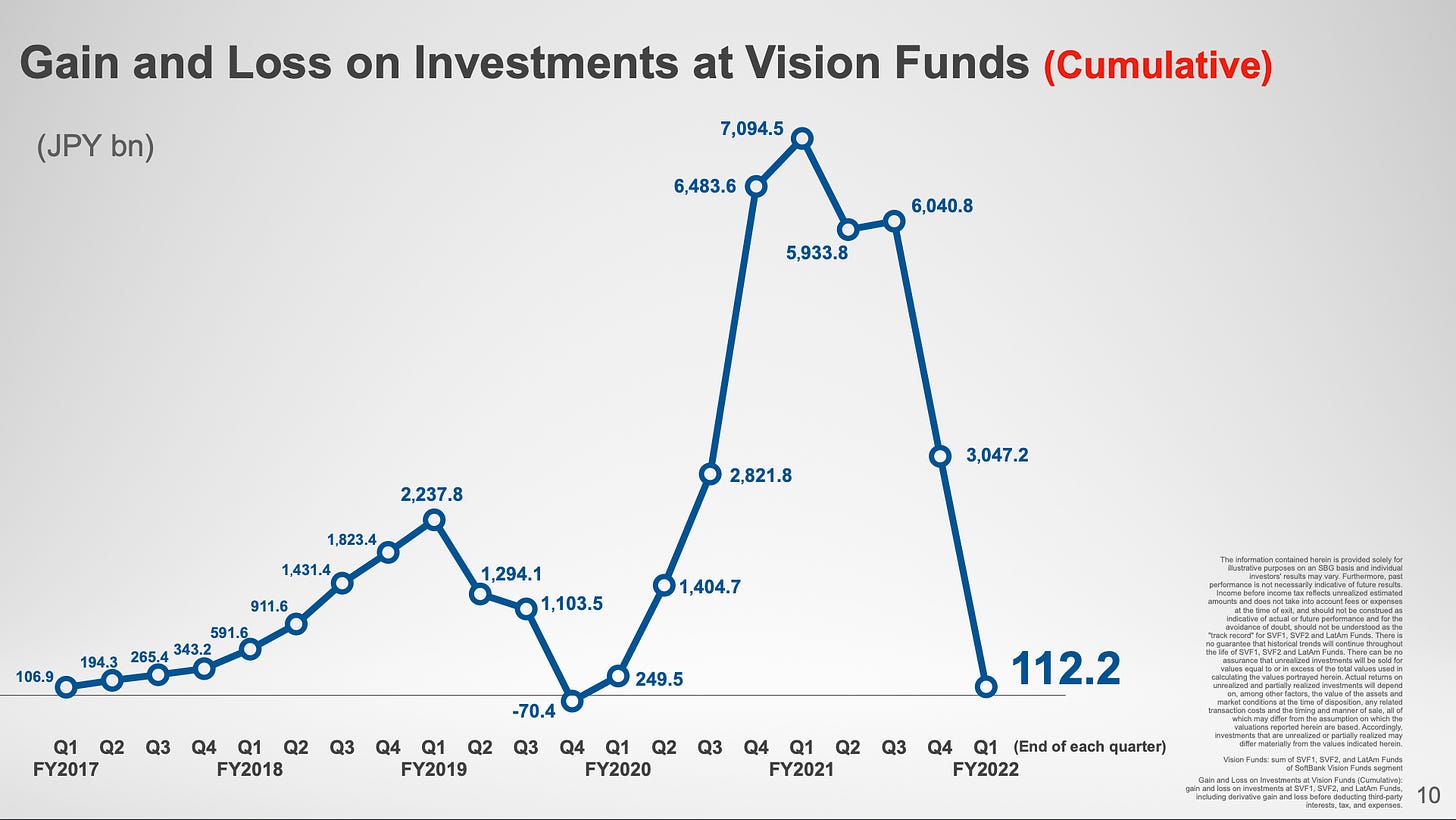

The Vision Fund’s downturn looks daunting even by Softbank's volatile standards. Son’s investments suffered between 1Q19 and 1Q20, with a drop of approximately $14 billion in cumulative value, but this latest decline is much worse. Between 1Q21 and 1Q22, the cumulative value of SVF’s holdings fell by more than $48 billion.

“I was so lucky. I was so close to falling down the cliff,” Son once said of his dotcom collapse. “I don’t know if I could do it twice.” If Son is to save his venture practice, he will have to find a way.

Learn the playbooks of today's global giants. Join 63,000 others to get our next Sunday briefing.

Twilight: In Pursuit of More Life

Even amidst the gloom, Masayoshi Son could not help himself. While the portrait of Tokugawa Ieyasu seemed a reflection of Son’s bitter mood, it also served as a subtle reminder of the Softbank chief’s ambitions. Ieyasu may have lost the Battle of Mikatagahara, the reason for his frown, but he won the war.

In 1603, thirty years after the disappointment of Mikatagahara, Ieyasu was named shogun of Japan. He had outlasted his peers and unified warring territories. The Tokugawa shogunate ruled for the next 260 years.

Son has always wanted to build an enduring empire. If he is to follow Ieyasu’s trajectory – bouncing once more from defeat to victory – he will need to act decisively and change some of his most stubborn habits.

Before considering drastic moves, we must first understand the state of play.

Failed conquests

A very simple question: has the Vision Fund performed well?

A very simple answer: no.

The losses in cumulative value discussed above suggest as much, though they don’t illuminate Softbank’s relative performance. How has the Vision Fund managed compared to other venture firms? What do its returns look like compared to the broader market?

Steve Kaplan, a professor at the University of Chicago’s Booth School of Business and creator of a private equity benchmarking approach, shared his assessment of SVF 1. “Performance has been disappointing,” he said. “As of March 31, 2022, Vision Fund 1 was marked at a value of $116.2 billion compared to a cost of $87.5 billion. This is a multiple of 1.33.”

Kaplan outlined how that compared to the broader ecosystem. The average multiple for 2017 vintage funds stands at 3x, while the median is 2.4x. “The median fund did much better than the overall stock market and almost twice as well as Vision Fund 1. [It] would have been in the bottom 10% to 15% of performance among VC funds raised in 2017,” he added.

These figures may not even capture the full extent of the matter. Since March 31, markets have declined, likely further damaging SVF 1. “Since then, the value of the Vision Fund has declined to the point where it may be worth less than the investment amount of $87.5 billion,” Kaplan said.

And yet, between the two Vision Funds, the debut vehicle may end up the better off. “Over time, it may be ok,” a former investor said. “The years it was deployed in – those were not insane years. There was some good stuff in there. It’s not obvious it’s going to be crap.” They added the debt SVF 1 took on may complicate matters. “The question is: how much will equity participants get? Because there’s debt ahead of it.”

Despite SVF 1’s underperformance, SVF 2 could prove worse. “So much of it was deployed in 2021,” the source noted, “You have deep losses on paper.”

Kaplan compared last year’s euphoria to a previous cycle Masayoshi Son will remember well:

The recent boom, helped by the Vision Fund, but also Tiger Global and others, is similar to the dotcom boom. In the dotcom boom, valuations became very high. At some point, the market decided those valuations were much too high, and they came down and stayed down for some time. The high valuations of 2020 and 2021 have now declined. If the dotcom experience is a guide, they will not get back to those levels for some time.

Softbank is already feeling the pain; it may need to endure it for years to come.

Heir inapparent

The Vision Fund has taken a financial toll on Softbank. Perhaps even more importantly, though, it has reinforced Son’s most dictatorial instincts. Somehow, six years after Masa iced his heir apparent, Softbank’s succession plan is even hazier.

The Machiavellian culture and chaotic decision-making structure at the Vision Fund contributed to this absence. For one thing, it cemented Son as a sole decision maker, giving little chance for existing leaders to develop authority or new talent to take on ultimate responsibility. Moreover, those with some measure of power have nearly all departed, leaving a vacuum between Masa and his workforce. “There’s no real management layer,” a source noted, “Because there’s no one Masa knows anymore.”

Over the past couple of years, Softbank has seen a mass exodus of leaders, including Rajeev Misra, Marcelo Claure, Akshay Naheta, Colin Fan, Deep Nishar, Ervin Tu, Jeff Housenbold, Michael Ronen, Praveen Akkiraju, Shu Nyatta, Paulo Passoni, Munish Varma, and Yanni Pipilis. Many are starting funds of their own.

Who is left? The rager has ended, and in Masa’s vast cavernous mansion, a few stragglers remain. A former employee pointed to Ron Fisher and Yoshimitsu Goto as the only two long-time lieutenants still with the company. At seventy-two and fifty-nine, respectively, neither is likely to represent Softbank’s future.

“I don’t know what the organization is,” an ex-employee said. “It’s a bunch of new people, relatively speaking, with Masa as this autocrat at the top.” This state of affairs cannot continue.

The next move

What should Masa’s next move be? Much has been written about what the future might hold for Softbank, including Son taking the company private and rolling out new Vision Fund vehicles. To reinvigorate the conglomerate, Son should make five vital moves.

Stay public

Free up capital

Build a hierarchy

Begin a charm offensive

Capitalize on the downturn

There are good reasons why Son might want to take Softbank private. Every earnings report is big news, and posting heavy losses starts a media frenzy that can be hard to quell. Most venture funds don’t have to publicly share the fortunes of their portfolio, insulating them from such attention. Son no doubt looks at that protection with some envy. “I’m sure Masa has considered it,” one source noted, “but it would be expensive.” It would also come with meaningful complications. Softbank has convoluted tranches of debt, pegged at $22 billion as of June. Rather than going through the pain and cost of sorting that out, Softbank should stay public, conserving resources and focusing on the opportunity in front of it.

“I’d never bet against Masa,” one fund manager said, “But I wouldn’t invest in his fund either.” If Softbank wants to stay in the game, it will need to free up more capital. While the Vision Fund has been battered, Softbank itself is not about to blow up. “There’s no liquidity problem. Softbank actually has a lot of cash,” one source noted. Indeed, Softbank is estimated to have $35 billion in cash on hand, with more that can be made available. It has started shedding some of its considerable Alibaba stake – painful given its current price but probably necessary to appease debtors.

More money may soon flow into Softbank's coffers. Despite the frigid conditions, semiconductor company Arm is expected to test the public markets within the next year. Softbank acquired the firm for $32 billion in 2016. In May, one analyst suggested it might fetch $45 billion at IPO, though conditions have changed. Given Softbank’s total market cap sits below $60 billion, just recouping its initial investment would be extremely meaningful. “Arm is a high-quality company,” a source said. While Softbank might have logged record losses in its last financial year, Arm posted its best-ever results. Revenue came in at $2.7 billion, an increase of 35% from the year prior.

In tandem with increasing its cash reserve, Softbank needs to build a management team for the long-term. This is easier said than done and will require genuine buy-in from Son himself. He should no longer expect to be the sole, decisive voice on every deal. Though having every investment checked by a team in Japan was a reasonable short-term defense against the “rosy stories” Son received, it is not an enduring solution. Uniform valuation and assessment practices should be implemented and enforced. Recent reports from Softbank suggest more rigor here, but only those inside the beast know how well it is running.

As part of this structuring, Son must restart his search for a successor in earnest. While he may argue he has been doing so, there have been no public auditions since Arora. Misra may have had Son’s ear but never seemed to be seriously in the running for the top job. Marcelo Claure and Katsunori Sago were occasionally mooted, but both have since left.

If Softbank wants to continue investing at, or near, its previous scale, rebuilding credibility in the U.S. is vital. While other regions are developing strong markets, no other geography compares to the States when it comes to producing elite companies – especially as China’s ecosystem has fallen into chaos. To do so, Softbank must commence a charm offensive. It has a great deal of work to do. As things stand, the Vision Fund isn’t well thought of in U.S. venture capital circles. “It’s kind of a running joke,” one person said. Debacles with WeWork et al. have created an image of Softbank as an unthinking gavage-capitalist, stuffing money down the throats of startups. Founders that have seen the results of this approach may be wary of bringing Softbank into the fold.

Combating this perception may take some time, but it is not impossible. First, Son should be more visible in the American tech press. While Softbank is often written about, it has been some time since he’s done a long-form interview. Indeed, his 1992 discussion with Harvard Business Review may still be his best interview. Could we see Masa in Joe Rogan’s bro-basement? Or appearing as a Bestie Guestie on the All-In podcast? These may seem frivolous, but Softbank is missing soft power in America. Few can charm as effectively as Masayoshi when given an audience.

Softbank can also buy its way back into Silicon Valley’s good graces. Beyond sponsoring events, publications, and other grassroots initiatives, it should implement a proactive fund of funds strategy. Every promising seed fund should receive a call from Softbank’s team, asking to invest. With relatively small investments – often as little as $1 million – Softbank can purchase goodwill with a rising crop of venture investors. As it shows itself to be a thoughtful, constructive partner to these funds, it can position itself to see breakout companies first. Tiger Global has done this reasonably successfully over the past few years.

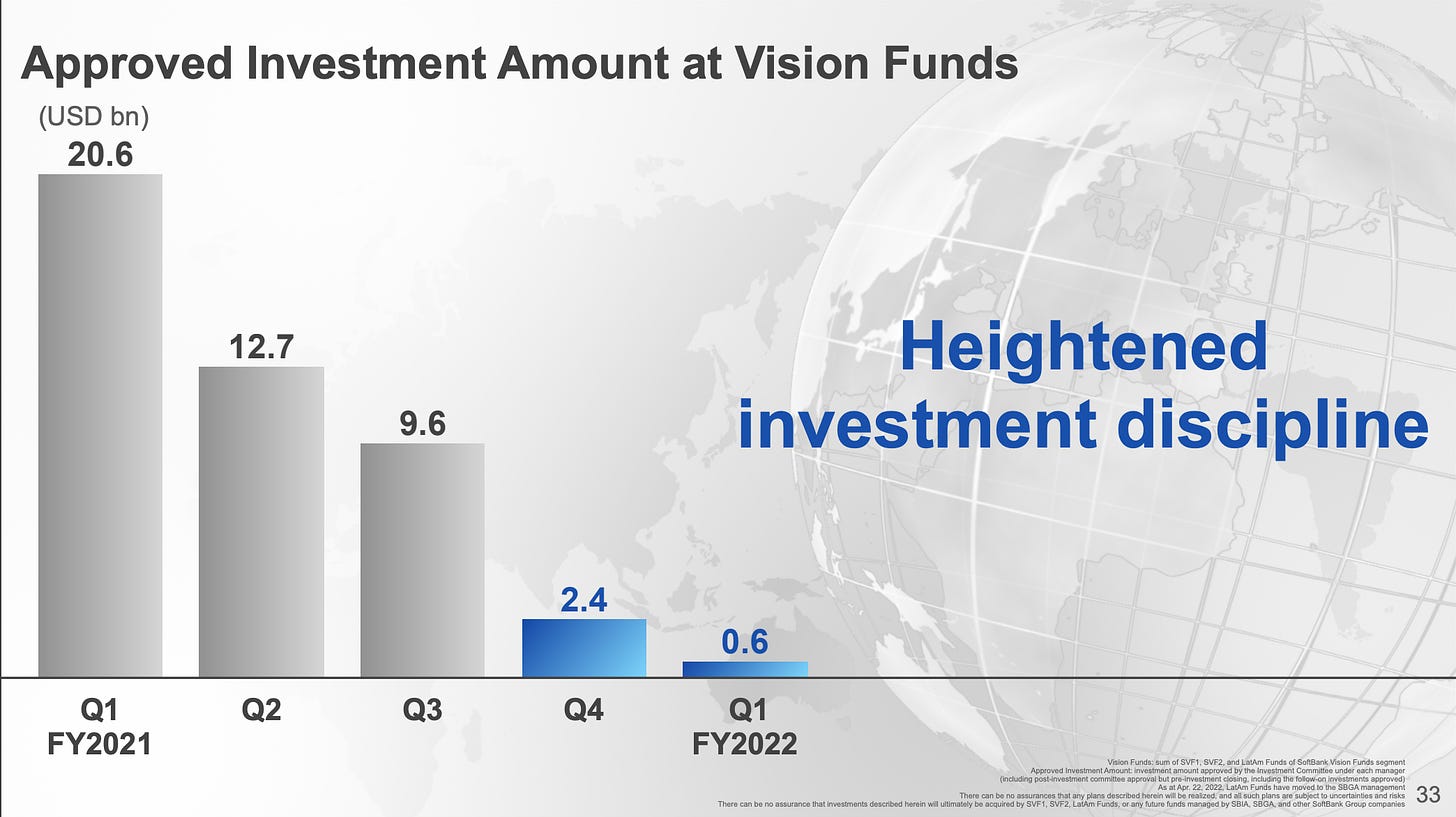

Finally, Softbank needs to capitalize on the downturn. For the past few years, Softbank has not only seemed to be out of sync with the market but perfectly out of sync. When valuations were relatively low in 2019 and early 2020, it pulled back; when tech roared to its peak in 2021, it torched capital. Now that a downturn has arrived, Son has shrunk SVF’s capital to $600 million. A year earlier, it was $20.6 billion.

Such caution is understandable. Son himself said: “Now seems like the perfect time to invest when the stock market is down so much, and I have the urge to do so, but if I act on it, we could suffer a blow that would be irreversible and that is unacceptable.”

But Son has never played it safe. “Masa always takes big swings,” one source said. “He’s a slugger all the time. He’s never a base hitter.” It also doesn’t seem as all-or-nothing as Son’s comments suggest. Given Softbank’s cash position – and potential to raise more – there seems to be latitude to keep writing big checks without jeopardizing the mothership. Impressive companies with great potential are on-discount at the moment; Softbank shouldn’t miss the chance it's been presented.

Perhaps Son is merely steadying the ship before his next assault. “The smart move is to forget the past,” one investor said, “And then be even more aggressive.” Few know how to do that better than Son.

Softbank may yet slow the sun from setting. There may be another surge, another triumph, another full-pump-Masa monologing about the future, and sorrow, and the robots we will love, and that will love us back. Even at this dark moment, it doesn’t take too much imagination to believe his empire could stretch a little further, push the boundaries a little more.

It’s hard not to feel like we’re coming to the end of something, though. Softbank will not disappear when Masa leaves, but it will not be the same. The Vision Fund may live on in a third incarnation, but it cannot be allowed to take the same bloated shape. The ruins may not be as dramatic as we imagine, but there must be rebuilding.

From the very beginning, Softbank has been inextricable from its creator – Son’s id and ego manifested in corporate form. It is time for the company to leave its founder behind and prepare for a new era.

The Generalist’s work is provided for informational purposes only and should not be construed as legal, business, investment, or tax advice. You should always do your own research and consult advisors on these subjects. Our work may feature entities in which Generalist Capital, LLC or the author has invested.