Mercury is Ready for the Moment

The unicorn banking platform built on a network of partner institutions is profitable, growing rapidly – and ready to become SV’s new standard.

Brought to you by Mercury

More than 100,000 startups trust Mercury for their banking needs including checking, savings, credit, treasury, and venture debt services. It’s rare for a bank to be loved – but Mercury’s elegant product and extreme usability has made it a favorite among startups, venture capital firms, and e-commerce businesses.

As well as saving founders and finance teams time, Mercury offers security and protection. Its recent Vault product automatically provides FDIC-insurance up to $5 million – 20x the typical coverage.

Please note: As always, this is not financial advice.

Actionable insights

If you only have a few minutes to spare, here's what investors, operators, and founders should know about Mercury.

A decade in the making. CEO Immad Akhund launched Mercury in 2019, but he had been waiting for a better startup bank to emerge since 2013. He has built a platform designed to solve the pain points he identified as a founder – one that gives time and security to entrepreneurs.

Owning the bank account. One investor described the current fintech landscape as a “Game of Thrones.” Mercury is competing against other energetic, innovative businesses, all of which want to be startups’ primary financial platform. One of Mercury’s edges is that its core offering is a bank account, which acts as a client’s business hub. By owning that relationship, Mercury is well-positioned to add ancillary products like treasury services, credit, and venture debt.

Diversified revenue. Mercury has succeeded in that rarest of startup achievements: profitability. Better still, the banking platform is able to rely on multiple revenue streams, monetizing through deposits, interchange fees, foreign exchange, and beyond. The result is a company capable of growing in divergent macroeconomic environments.

Uncharted waters. We are in the midst of what looks like a full-blown banking crisis. Storied institutions are straining under macroeconomic pressures; some are buckling beneath them. Such dynamism could reward a fast-growing startup, but also introduces considerable peril. No one wins if the ecosystem deteriorates.

The new standard. Tech lost its historic bank of choice in the past few weeks. The demise of Silicon Valley Bank leaves a massive hole – of systemic importance – that must be filled. Mercury has the opportunity, and perhaps responsibility, to become Silicon Valley’s new standard bearer.

This piece was written as part of The Generalist’s partner program. You can read about the ethical guidelines I adhere to in the link above. I always note partnerships transparently, only share my genuine opinion, and commit to working with organizations I consider exceptional. Mercury is one of them.

"I'm sure it will be fine. Right?"

On Wednesday, March 8, Mercury CEO Immad Akhund was cautiously optimistic. He had heard rumblings about trouble at Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) for several months, but like the rest of the industry, Akhund believed the forty-year institution was equipped to ride out any turbulence. Even the news that SVB was planning to pull together a last-minute $2 billion round of funding, though concerning, didn't feel cataclysmic. After all, this was an institution valued at nearly $20 billion earlier this year with $175 billion in deposits – partner to power brokers like Andreessen Horowitz, Founders Fund, Kleiner Perkins, Insight Partners, Bain Capital, and more than 2,500 other venture firms.

In some more sanguine strand of the multiverse, that is where the story might have ended: SVB raised $2 billion, quelling the panic in its tracks. If the 2020s have one ultimate message, however, it is that we live in the most chaotic timeline. This is the age of superbugs and superbubbles, lockdowns and collapses. Welcome to the roaring twenties: a decade of pandemonium.

The days that followed stayed true to that spirit – at the cost of SVB and the sanity of many in the startup ecosystem. On Thursday, Akhund woke to a wave of new Mercury sign-ups as worried customers fled the flailing incumbent. Friday brought the death knell: the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) stepped in to take control of SVB, no longer imperiled but incapacitated. On Sunday, the FDIC declared a "systemic risk exception," allowing the government to backstop uninsured deposits. It is not an exaggeration to say that without such decisive action, the tech sector might have undergone a nuclear winter, an epoch of death in which only the indestructible survived. For now, at least, the worst has been avoided.

For Mercury, this five-day spell in March may prove the most consequential of its history. Though it has had plenty of eventful moments on its path to becoming a profitable banking platform valued at $1.6 billion, no episode tells us more about Mercury's DNA and preparedness for the post-crash age. As its largest rival imploded, Akhund did not gloat; he built. Over that hectic weekend during which SVB sought an acquirer and founders fretted over making payroll, Mercury's team set to work constructing a new product designed to make customer deposits safer than ever. They did so even while onboarding a record number of customers, with Akhund working around the clock to handle support requests and personally responding to customer queries.

That Monday, Mercury announced Vault, a risk management product providing $3 million in FDIC insurance – 12x the typical coverage. By that Friday, Mercury announced its protection had been increased to $5 million. Mercury can only offer these unusually high safeguards because of its core model: it is not a bank but a layer on a network of partner institutions. At this level, at least, there is no single point of failure; risk is distributed, and each node in the network can provide insurance.

Another major launch swiftly followed. Recognizing that many venture firms had found themselves unhoused by SVB's demolition, Mercury launched a dedicated venture offering on March 22, providing the same protections, support for VC-friendly jurisdictions like the British Virgin Islands, and bespoke customer support.

Mercury's response to tech's banking crisis suggests it is prepared for the opportunity and responsibility that stands before it. Silicon Valley needs a new bank. A multi-billion dollar hole has opened that must be filled. Mercury's customer obsession, networked model, innovative product suite, and grace under fire means it appears ready for the moment.

Origins: Building a better bank

Immad Akhund finally had a chance to breathe.

After eight years of building, he'd finally sold his startup Heyzap. It represented the end of a long, convoluted journey that didn't always seem set for a successful outcome.

In 2008, he founded the business with fellow University of Cambridge graduate Jude Gomila. They'd gotten off to a strong start, gaining acceptance to Y Combinator and eventually raising $8 million from iconic firms like Union Square Ventures and legendary investors like Naval Ravikant and Chris Dixon.

Startup success is rarely so simple, though. While Akhund and Gomila had initially set out to build a flash gaming portal, finding product-market fit proved challenging. "We had four full pivots," Akhund recalled, with Heyzap eventually morphing into a toolkit that helped gamers optimize in-app advertising revenue. That was the business that attracted the attention of RNTS Media and secured a $45 million acquisition. For Akhund and Gomila, it was not only a vindication of their "relentless resourcefulness," as Y Combinator founder Paul Graham might have described it, but also a relief – the end of a saga that may have ended in triumph but involved plenty of frustration.

Despite the intensity of building Heyzap, Akhund didn't sit still for long. As early as 2013, another business idea began to play on his mind. In running his last company, Akhund encountered constant friction, particularly when moving and managing money. Even in Silicon Valley, the home of innovation, sending or receiving wires was an ordeal, the kind of pain that belonged in the age of fax machines and dial-up internet – not the software capital of the world. Even compared to London, where he'd grown up after emigrating from Pakistan, the state of affairs had seemed better evolved. "The banks we used in London were better," he said. "Money moved quicker; the mobile experience was more advanced."

While building a company had given Akhund broad exposure to the subpar banking experience startups faced, the eccentricities of Heyzap's model hammered it home; Akhund's firm handled payouts for game publishers, making money movement an essential operation. "We had to send money to 600 publishers at the end of each month," Akhund recalled. "It used to take us three days to get it all right."

When he'd tried to streamline the process with technology, he'd met a series of dead-ends. "I'd call up these banks and ask if they had an API we could use. They'd say, 'Sorry, we don't know what you're talking about.'"

The pain banking caused Heyzap convinced Akhund of the opportunity in the space, a belief that solidified into a more tangible business idea in 2013. Though institutions like Silicon Valley Bank might have made their name serving the sector, they'd hardly adapted to the software revolution and didn't seem sufficiently driven to overhaul their technical capabilities radically. Updating a few features here and there might help, but Akhund doubted it would be sufficient to address entrepreneurs' challenges. A comprehensive alternative was required: a banking platform designed for startups powered by software.

Someone needed to build it, Akhund thought. But it wasn't going to be him. "I was busy with my own company. I wasn't going to quit Heyzap to do it."

"I was sold pretty quickly"

Two years later, a company attempted to build Akhund's concept. In 2015, Seed followed in Heyzap's footsteps, raising from Y Combinator. Akhund viewed their entry into the market with both relief and regret. He was glad that someone was finally trying to solve this problem, but part of him wished he had been the one to do so. "I remember thinking it was a shame I couldn't build it."

As it turned out, Seed's founders might have shared Akhund's enthusiasm for the problem space, but they diverged when it came to constructing a solution. "They executed it very differently than I'd visualized it," Akhund said. That meant that by the time Heyzap's founder was ready for his next challenge; his vision had yet to be tackled.

In January 2017, Akhund began building his next startup: Mercury. He recruited two Heyzap executives to join him, former VP of Business Development Jason Zhang and software developer Max Tagher. As Tagher remembers it, he didn't need much persuading. "I think I was sold pretty quickly," he said. "It was simple: something bad exists in the world, and we can make it better."

Mercury's founders weren't necessarily the natural choice to tackle the opportunity. After all, none of them had built a business in fintech before, despite Heyzap's convoluted payment operations. "I wasn't a fintech entrepreneur at that point," Akhund said. "And the idea of building this business as a product or software entrepreneur wasn't obvious."

Beyond the clear need for a better startup bank, Akhund was compelled by the scale of the opportunity in the space. "A lot of startups are really features," he said. "I was looking to build something for the next ten or twenty years. If you could figure this problem out, it could be a lot bigger than a feature. It could be a platform."

Recognizing how much he had to learn about fintech and feeling somewhat daunted by the prospect, Akhund set about learning. Over the next few months, he spoke to as many fintech lawyers, entrepreneurs, and investors as possible, including executives at Monzo, Aspiration, Simple, and N26. Akhund estimated he conducted more than 90 interviews to get a sense of the landscape, validate his feature set, and affirm his conviction. "When you first approach something like this, it seems overwhelming," he said. "But by the end of these ninety conversations, I knew the problem wasn't trivial – but I had a path to follow."

In August 2017, Mercury raised $6 million from Andreessen Horowitz (a16z) to chase its vision. For Alex Rampell, backing Akhund was an easy bet to make. "It was a really good idea," the a16z General Partner remarked. "There are some very strange niches – like startup banking – that are really quite big. And once you start holding funds for these companies, there are so many amazing things you can do."

"Two years later, we would have been too late"

With money in the bank, Akhund set about building. With the benefit of hindsight, Mercury's CEO couldn't have chosen his moment better. "If I had tried to do it two years earlier, I don't think it would have been possible," he said. "And if we had tried two years later, we would have been too late." Among other factors, issuing cards has become easier over the past few years, allowing digital-first products to extend into the physical world.

Rather than constructing a card business, Akhund focused on two vital features: wire transfers and coverage for non-US residents. Both were products that had personal resonance and market utility.

Wire transfers were ubiquitous among startups. They were, after all, the primary way companies received the funding they had raised, and yet, despite their prevalence, processing them was fusty and convoluted. Out of the gate, he wanted Mercury to solve this issue once and for all, making sending and receiving wires a seamless experience.

Supporting non-US founders felt equally important. "I didn't want to start a bank that wouldn't have been able to serve me," Akhund said. Given how many Silicon Valley entrepreneurs were immigrants, it was more than an ideological concern.

Beyond these core features, Mercury sought to incorporate the fundamental functionality of a traditional bank. Akhund knew it was all very good to surprise and delight with design and usability, but some degree of product breadth was nevertheless essential. "If you're missing an obvious feature, it breaks people's trust," he said.

Despite Akhund's experience, getting the company off the ground with that feature set wasn't easy. As we'll discuss in greater detail, Mercury is not a bank. It is, instead, a banking platform built atop partner institutions. Shipping the first version required devising the right product suite and a partner bank that would enable it. A false start with one partner institution delayed proceedings. "We integrated almost all the way with this organization," Akhund said. "They made promises about the wire transfer feature and supporting non-US residents. But they didn't follow through."

In 2018, Mercury restarted the process with a new partner and developed their platform. By April of the following year, they were ready to launch.

"It just grew and grew"

Akhund had seen enough in his entrepreneurial career not to get his hopes up. "Usually, when you launch something new, nobody cares," he said. "You have to fight for distribution." Though that may be the norm, it certainly wasn't the case for Mercury.

On April 19, 2019, Akhund, Zhang, and Tagher shared their new creation with the world. To their surprise, the world loved it. "We launched and it just grew and grew," Akhund said. "That was especially true for the first six months – we were growing by 30-40% month over month." In truth, it didn't even take that long to stun Akhund. By the end of Mercury's first week, a customer had transferred $1 million into their new account – a stunning sign of faith for such a young product. "It told us we had a really good feature set," Akhund said. "And that people were really frustrated with the other banks."

Mercury's impressive start attracted the attention of investors. Saar Gur had met Akhund back during his Heyzap days. Though the CRV general partner hadn't invested in that startup, he'd been impressed by the grit and ingenuity of its founder. "He and Jude were very scrappy," Gur said. "They zigged and zagged and reinvented themselves." In Mercury, Gur saw an impressive founder taking on a significant problem. The polish of Mercury's initial product only cemented his interest. "I gave them a term sheet for the Series A when the product was just seven to ten days old," Gur said. CRV led a $21.3 million round with participation from Flexport founder Ryan Peterson and Plaid CEO Zach Perret.

The downside of the hot demand for Mercury's product was the strain it placed on the team. "There were just nine of us at the time and we were not expecting such a strong reception." The rest of 2019 brought the kind of suffering that founders dream of. Mercury's team worked tirelessly to onboard new customers, provide robust support, and upgrade their capabilities. Akhund often personally responded to support tickets and helped new customers get up to speed.

The following year brought a new set of challenges. Akhund had always pursued a hybrid model for Mercury, but the pandemic's outbreak pushed the company to a fully remote setup. While those operational shifts introduced new complications, the more significant change came on the business side.

"I can probably stop worrying"

Almost exactly a year after Mercury launched, the Federal Reserve announced it was lowering interest rates to between 0% and 0.25%. Akhund couldn't have asked for a worse birthday present. Until then, most of Mercury's revenue had come from monetizing deposits, with partner banks sending a rebate on capital held. (Partners either sweep money to other banks who pay a rate for the deposits, or they loan deposits directly. In either case, Mercury receives a rebate from these partners.) Virtually overnight, the source of 60% of Mercury's earnings had disappeared.

While greener founders might have assumed their company had product-market fit after the bullish inaugural year Mercury had enjoyed, proof for Akhund arrived the next month. Despite the Fed crushing the company's business model, Mercury continued to grow, drawing customers from a new sector: e-commerce. "In May, we just started to go really fast in e-commerce," he recalled. "We'd focused on serving VC-backed startups, so that surprised us. But we were one of the only places to get a bank account without going to a physical branch. Seeing us survive the initial shock of covid and then expand fast in a new category – that was when I thought, 'Ok, I can probably stop worrying. We probably have product-market fit.'"

Though emboldened by that development, Akhund didn't push Mercury to grow at an unsustainable pace. "We went through this reckless period in 2020 and 2021 when it paid to be aggressive and burn lots of money," a16z's Rampell said. "Immad was smart enough to say, 'This is crazy. We're not going to do anything irresponsible.'" While less disciplined competitors scaled headcount, Akhund held back. "I've never been 100% sold that more people means you go that much faster," he said. "It usually means you go slower."

Though he kept his team lean, Akhund did take advantage of the hot market to raise another funding round. In May 2021, Michael Gilroy of Coatue led a $120 million Series B that valued the business at $1.6 billion. "Business banking is one of the biggest ideas out there but also one of the most simple," Gilroy remarked. Beyond the opportunity in that category, Gilroy particularly liked Mercury's product strategy, its delightful UX, and customer obsession.

Immad Akhund's mix of restraint and savvy meant that Mercury entered 2022's downturn in strong shape. It boasted an expanded product, a largely intact war chest, and healthy revenue. When the Federal Reserve started raising rates in March, a company that had learned to monetize in a zero-interest environment suddenly found itself flush. Once again, Mercury could monetize on deposits, and as rates rose, Akhund's company crossed that rarest of thresholds for hypergrowth companies: profitability. As tech and banking roil in 2023, that endows Mercury with enviable strength.

Product: Resilience and range

"Less, but better."

That was how Dieter Rams described his ethos. Though Rams' name may not be heard much in tech today, his philosophy and aesthetic inspired some of the sector's most beloved products, particularly those of Apple. Former Chief Design Officer Jony Ive described the German's work as "beyond improvement."

Mercury brings Rams' approach to the world of software. Akhund's product does not try to do everything, nor does it convince through clutter and convolution. Though powerful and fully featured, much of the genius of Mercury is how simple, how usable, it feels. "Design should not dominate things, should not dominate people," Rams once said. "It should help people. That's its role."

The care and craft Mercury brings to every button, form, and feature are done not out of vanity or the egoistic demands of an overreaching designer. It is to save time and make life easier for the user. It is to help people – and to do so as efficiently as possible.

To fully grasp Mercury's product, we must understand its foundational structure, product suite, and ultimate impact.

The structure

One of the seemingly paradoxical truths of fintech today is this: if you want to create a better bank, you probably shouldn't build one.

The capital requirements and regulatory complexities overwhelm early-stage companies and slow the process of reaching product-market fit. Even if a startup manages to become a formal financial institution, it may not make for a better user experience. As we'll discuss, acting as a layer on top of existing banks unlocks some powerful protections.

Instead of getting stuck in this morass, Mercury leverages a partner model. It works with Patriot Bank to run its credit card program and Apex Clearing Corporation to offer its Treasury product, which we'll explore further below. Mercury's two most critical partner institutions are Choice Financial Group and Evolve Bank & Trust. These organizations hold the bank licenses Mercury needs to provide its product and handle core functions like card issuing and operating checking and savings accounts.

That's not where Mercury's partnerships end, however. Both Choice and Evolve operate what is known as a "sweep network," a constellation of accounts across different banking institutions. When a customer deposits money into Mercury, what's actually happening is that it is being held by Choice or Evolve, who are, in turn, distributing the capital across up to twenty institutions like Morgan Stanley, Goldman Sachs, Wells Fargo, and many smaller, local players.

Our case study on Kleiner Perkins outlined how the venture capital firm found its first big win by incubating Tandem, a "fault-tolerant" computing system. Tandem succeeded by building a miniature network of computers, such that if one node malfunctioned, the remaining parties could pick up the slack and keep working. It represented a massive upgrade for financial institutions, healthcare facilities, and emergency services – all of which benefited from resilient computing.

By leveraging partner organizations' sweep networks, Mercury has constructed something close to "fault-tolerant" banking, where risk is distributed across a network rather than concentrated in a single node. It's a system that seems structurally better suited to handle financial turmoil, particularly in how Mercury leverages it.

Let's walk through an example.

Imagine you're a customer of Gallium Canyon Bank (GCB). You use the popular institution to hold $5 million in cash and have for several years. Despite its august reputation, over a few days, GCB disintegrates, driven by a mixture of mismanagement, changing macroeconomic conditions, and a bank-run dynamic. You would be right to be worried at this point. The FDIC insures accounts up to $250,000, just 5% of your total holdings. Barring governmental intervention, 95% of your cash will likely be lost.

Now, imagine you're a customer of Mercury. You deposit $5 million in cash onto the platform, handled by Evolve, who "sweep" your money into accounts at twenty separate institutions, including Gallium Canyon Bank. Assuming the broader banking system works as it should, GCB's failure might sound scary, but it shouldn't put your funds at risk. Because your cash has been distributed across twenty partners, only $250,000 should be jeopardized by GCB's collapse – which would be covered by the FDIC anyway.

In addition to reducing risk by distributing funds, Mercury's model also helps it maximize coverage. Since capital managed by Mercury is swept across multiple institutions, the company can draw on that insurance multiple times over. Though Akhund's company was already offering $1 million in FDIC insurance before Silicon Valley Bank's ruination, it improved the offering in the following days. Today, Mercury Vault provides insurance up to $5 million, 20x the regular rate. This is only possible because of its networked model. Other fintechs, such as AngelList, also leverage sweep networks; in the coming years, I expect many other players to adopt this approach.

Of course, Mercury's model is not infallible. Though Akhund's company would be better positioned than many to weather a broad, sustained banking crisis, the failure of multiple institutions would strain even the most robust network.

Mercury selects its banking partners carefully to ensure it stands on strong footing. Catherine Ordeman, Mercury's Head of Banking Partnerships, outlined how her team runs this process.

First and foremost, Mercury optimizes for security. The company conducts due diligence on all its partners to assess their financial health. It only works with those with "robust capital ratios, stable assets, and a track record for profitability," as Mercury's website outlines. Ordeman noted: "Our number one priority is to ensure customer funds stay safe."

Safety is a necessary but not sufficient condition for Mercury. Akhund started the platform to revolutionize the banking experience – something not every partner can support. Finding forward-thinking collaborators is the final step. "We look for partners that allow us to innovate and own the customer experience," Ordeman said. "We want to be able to respond to customers' requests and keep making the product better."

The product

Whether by luck or skill, Immad Akhund chose the perfect product to build first. Mercury's CEO started with the most basic offering: a bank account.

It was an inspired move. Though bank accounts might seem simple or boring, they're a locus of influence, a fintech foothold. Coatue's Michael Gilroy explained: "The bank account is the nucleus. It's where you're immediately sending your cash as you make it, and it knows the credits and debits of your account. When you have that information and that relationship – you can do really powerful things." (Long-time readers may recall that some of Goldman Sachs' recent tech efforts are oriented around amassing this power.)

Before alighting on its ancillary products, however, it's worth taking a moment to appreciate Mercury's core offering. The first thing to say about the company's product is that it is beautiful. Every button, interaction, pixel, and gradient has been thoughtfully constructed to create an effortless experience.

Even after being a Mercury customer for nearly three years, I remain struck by how enjoyable the product is – how different it feels from every other banking software. Typically irritating tasks like sending a wire, generating an invoice, or searching for a transaction become almost pleasurable thanks to Mercury's attention to detail. For example, rather than relying on a cluster of dropdown boxes and modules to find a transaction or payment, Mercury makes it trivial to conduct a rich search across your on-platform activity. It's a perfect example of less, but better.

That reaction is a common one. CRV's Saar Gur highlighted how unusual it was for a B2B platform like Mercury to solicit so much adoration. "People love it," Gur said. "I've literally had people come up to me at conferences and say, 'Mercury is the best piece of software [I've used]. Better than Google.'" While customer appreciation is no bad thing in its own right, it also directly impacts Mercury's business. "So much of our growth has been word of mouth," Gur remarked. "In B2B products, that doesn't really happen." According to Mercury's data, approximately 50% of customers come through organic channels; partners and advertising contribute 20% each.

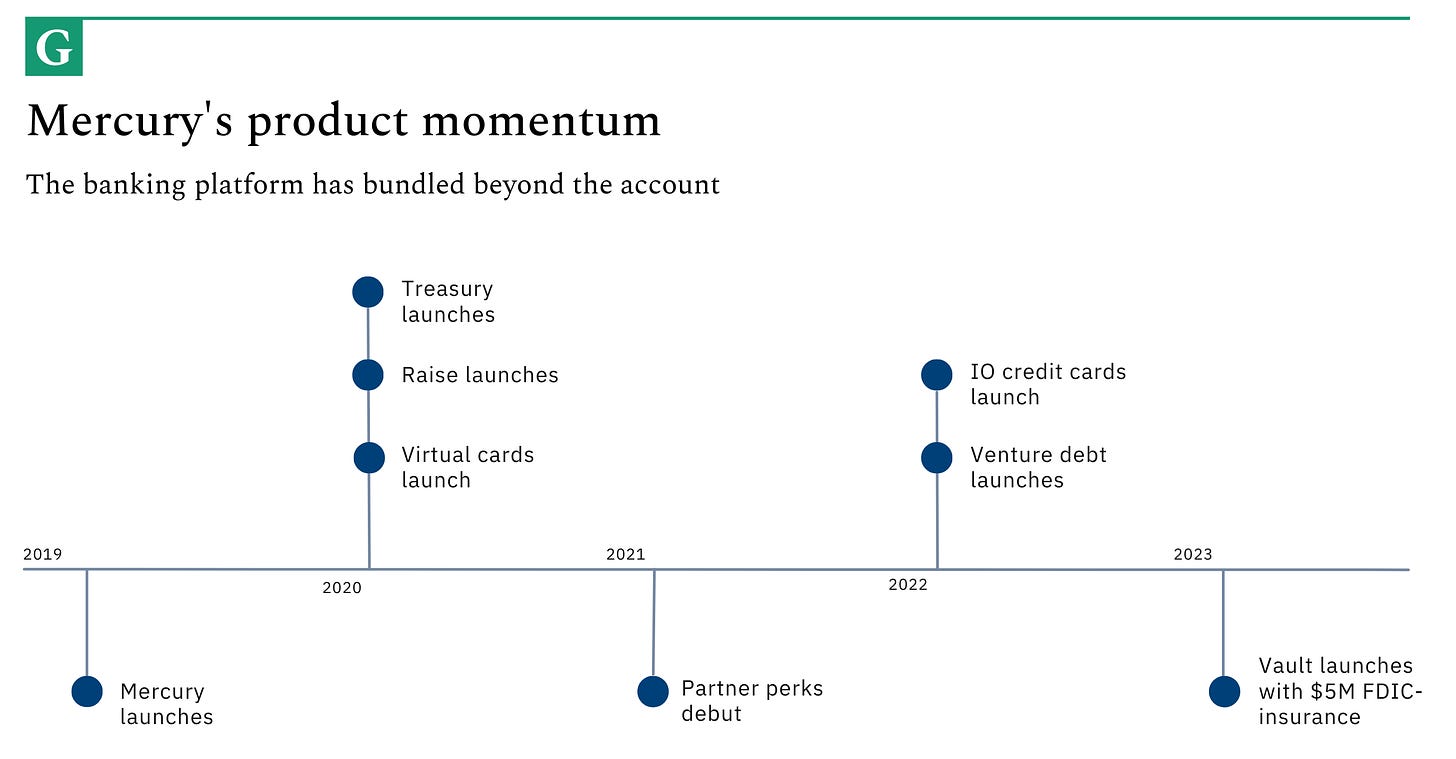

As Mercury's user base has grown, it has added products to its bundle. Alongside venture-backed startups, Akhund's platform focuses on two other segments: e-commerce companies and venture capital firms. Looking at its most significant product launches since its debut in April 2019 illustrates how Mercury has expanded its suite.

Let's outline a few of Mercury's major products:

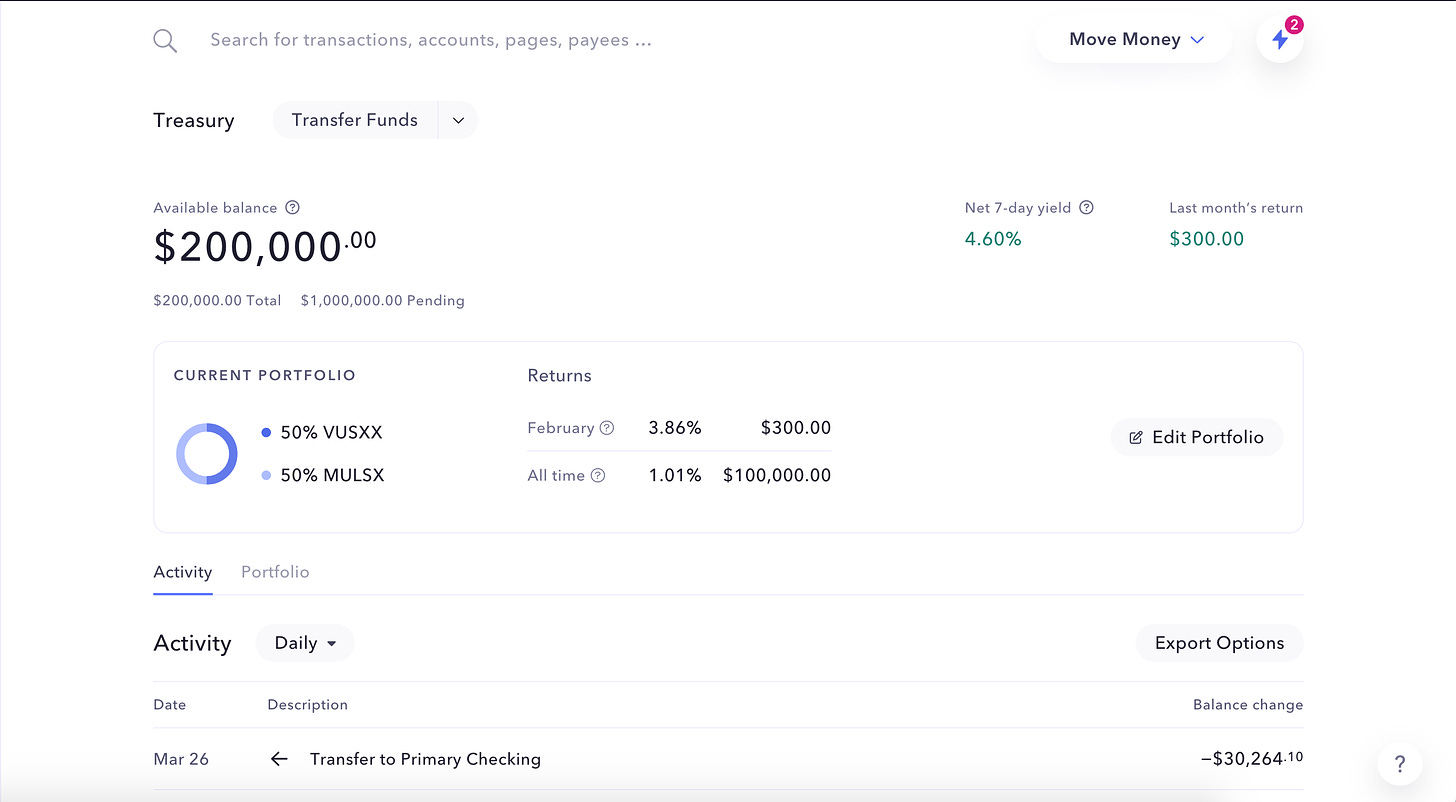

Treasury. Companies that want to earn a yield on their idle cash turn to Mercury Treasury. Customers can choose from five strategies offered by Morgan Stanley and Vanguard, earning up to 4.67% in interest* per year. It's a simple way for startups to extend their runway without leaving Mercury.

Venture Debt. Mercury offers venture debt to US-incorporated startup customers. Customers can see if they're eligible for dilution-free capital by filling out a quick questionnaire. In this respect, Mercury's venture debt appears less automated than focused providers like Capchase or Pipe. It does use a digitized due diligence process, looks to clearly state its terms, and makes it easy for founders to see where they are in the approval process. In that respect, it’s a much smoother experience than one might find with a traditional bank. Mercury charges an origination fee and interest on this product and receives the right to purchase common stock equity.

Credit. With its IO Mastercard**, Mercury entered the corporate credit world, edging closer to players like Brex and Ramp. IO users get 1.5% cashback on all spending, and Mercury offers intuitive controls to set spending limits and various user permissions.

Vault. As mentioned, Mercury recently launched Vault to provide even greater protection for customers. By default, accounts now have FDIC coverage up to $5 million through partner banks and their sweep networks. To protect funds beyond that threshold, customers can shift capital to Treasury, which primarily invests in a Vanguard money market fund that is 99.5% invested in US government-backed securities. Vault offers smart suggestions about when customers should move money to optimize security.

VC Banking. Though Mercury hasn't branded its latest update, it could be big news. Historically, VCs have made up 5% of Mercury's customer base, but that could expand rapidly post-SVB fallout. Its venture-focused offering makes it easy to set up separate-but-connected accounts for GPs, LPs, SPVs, and operating expenses, smoothing internal operations. Supporting the British Virgin Islands, Cayman Islands, and the United Arab Emirates entities is another impactful upgrade. Increasingly, Mercury looks like a compelling fit for small and mid-sized funds.

Beyond these core additions, Mercury has shipped dozens more improvements and augmentations. Taking a page out of the Stripe soft power book, Mercury launched Meridian in August 2022. The glossy digital publication celebrates builders and craftspeople, even making space for fiction.

Raise is another initiative aimed at celebrating and supporting the entrepreneurial ecosystem. The program aims to make fundraising easier by connecting early-stage founders with investors, supporting startups from their first check through a Series A. Since launching in late 2020, Raise has helped more than 700 startups which have gone on to raise more than $2 billion in capital. Mercury is clear about its ambitions with the program, noting, "We don't make any money from Raise…We want to help entrepreneurs succeed, and we know that capital is the lifeblood of high-growth companies. Raise is our attempt to remove some of the obstacles that founders face when fundraising, so it's easier for them to grow." It's a clever way to curry favor, capture customers early in their lives, and provide a genuinely valuable service to the startup community.

Ultimately, Mercury has effectively leveraged its shrewd starting point – the bank account – to build a comprehensive suite for entrepreneurs and investors. According to a16z's Alex Rampell, the result is a platform "100x better than any other on the market."

The impact

Mercury's value to customers is simple: it keeps you safe, saves time, and makes the most of your capital.

In addition to carefully vetting its banking partners, Mercury takes steps at the product level to keep funds secure. That includes automated fraud monitoring, customizable access controls, easy-to-set virtual card limits, and "receive-only" accounts that can take in capital but can't be withdrawn from. Mercury requires two-factor authentication via an authenticator app rather than running it via less secure text messages. Customers can also use Face ID or Touch ID to sign in, uncommon offerings for most banks.

For Ofek Lavian, such details make a significant difference. Lavian founded Forage, a payment processor for Electronic Benefit Transfers (EBT), which distributes government benefits to fight food insecurity. Today, more than 42 million Americans rely on federal programs to put food on the table and use EBT to pay for it. Forage has raised $22 million to make it easy for platforms like Shopify and Farmstead to accept EBT transactions so that recipients can buy groceries online.

While every bank user prizes security, the nature of Forage's work makes it particularly important. "We're a mission-driven organization," Lavian said. "This capital is used to help us do the most good in the world, and so it's really, really important to us that it's taken seriously. We trust Mercury wholeheartedly."

As well as keeping users' funds safe, Mercury has architected its platform to save customers' time. It does so by paying attention to tiny details and introducing powerful automations. An example of the former is the clever way Mercury invoicing works. If you upload a PDF to the platform, its optical character recognition (OCR) solution will automatically pull the relevant fields and input them into a digital invoice. On a one-off basis, features like this can save minutes; over time and across a team, they can add up to considerably more.

Dan Westgarth, COO of Deel, highlighted Mercury's time savings as a key advantage. "To add a user, change permissions, or make a payment – all of those things can be done incredibly quickly on Mercury," he said. "Whereas using an incumbent bank, those operations might take days or weeks."

In addition to being a user, Deel is also a Mercury partner. Deel customers can select Mercury as a payment offering, making compensating teammates hired via the remote work platform easy.

Mercury's automations are another time-saver. Rather than manually adjusting the funds in each account, users can set up rules. For example, the CFO of a startup that relies on Mercury could automatically shift a portion of excess capital to the Treasury product to take advantage of yields, but configure the system such that by a certain date each month, sufficient money is freed up to cover payroll costs. Given the amount of pain financial operations cause startups, this feels like ripe territory for further innovation.

Finally, Mercury helps businesses make the most of their money through its Treasury offering. As mentioned above, companies with balances exceeding $250,000 can seamlessly deploy part of their capital into five distinct strategies designed to extend their runway. The idea of generating yield on holdings isn’t new in the startup world, but the ease of use Mercury offers seems to have made a strong impression, along with the manner in which this service connects to its other banking features.

For Forage's Lavian, Treasury has been a game changer. "We just raised a bunch of money. We want to put it to good use, but we still have some idle cash," he said. "We looked elsewhere for treasury products. It was the best choice for us as a company [to use Mercury] when maximizing for efficiency, security, and yield."

By Lavian's estimates, Mercury Treasury will produce an extra $1 million in capital for Forage, with "very little work" for the team. "I can't underscore how amazing that is."

Model: In the money

"Being profitable is a very, very rare thing for a company at this stage," Coatue's Michael Gilroy remarked. So how has Mercury done it? How has Immad Akhund's young banking platform gained control over its destiny?

Scale

Mercury may be young but it is no longer a small company by startup standards. The platform boasts over 100,000 customers; last year, it processed more than $50 billion in transactions. It is likely still some distance from SVB's old asset base of $175 billion but Mercury’s size is nothing to sniff at.

As you might expect, most of Mercury's deposits come from startups. This segment makes up 80% as of Q1. E-commerce is the second largest segment, with 5%, followed by investors with 3%. Consultants, non-profits, and real estate firms are other relatively frequent users. It’s worth noting that while Mercury’s customer base is concentrated, its sweep network isn’t. That means that the startups it supports are being banked alongside businesses of different sizes, from disparate industries. It may sound like a small detail, but the manner in which deposit concentration harmed SVB, it is a potentially critical one.

Revenue streams

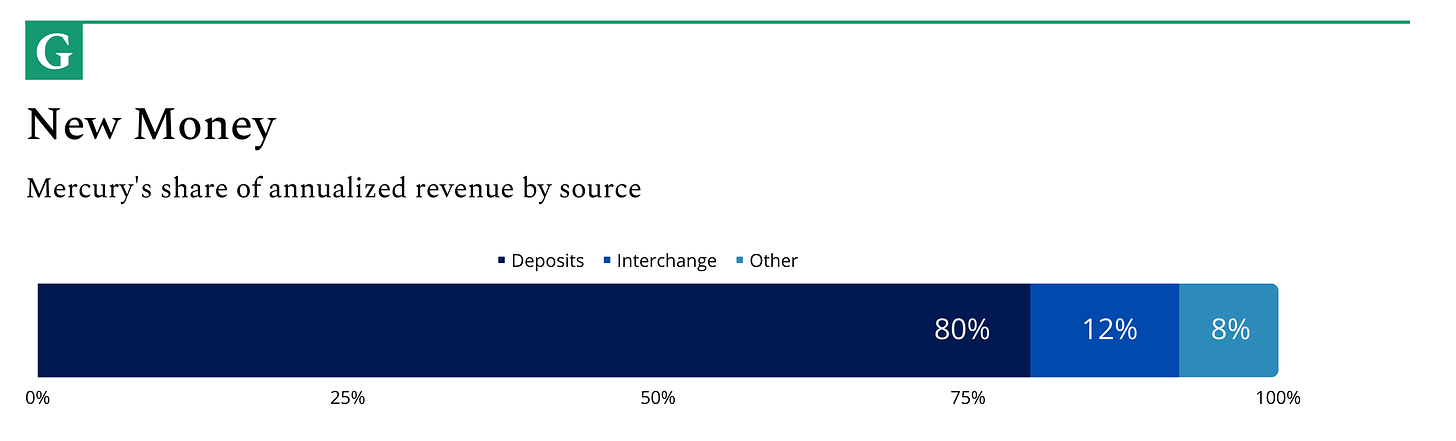

One of the appealing aspects of Mercury's business model is that it can make money in so many different ways from its user and deposit bases. As mentioned, Mercury historically monetized via deposits. The rate decline in 2020 eviscerated this revenue stream and forced Mercury to develop new ones. In particular, it focused on interchange revenue, earned thanks to its debit and credit offering. As Vice President of Finance Dan Kang remarked, that period "forced discipline" on the company, teaching it to adapt to different economic environments. "It's really difficult for a business to introduce new revenue streams later when that hasn't been part of its core DNA." Necessity required Mercury to develop that trait.

The rate hikes of 2022 and 2023 have sent Mercury's revenue into overdrive. "Now that interest rates are higher, we're making a lot more money," Kang remarked. "It's almost become this unplanned source of revenue."

Continued deposit growth and higher interest rates increased Mercury’s deposit revenue 8x year over year, as of February 2023. In total, deposits drove 80% of total revenue with interchange contributing 12%. AUM fees from the Mercury Treasury, interest on venture debt, and foreign exchange fees added the remaining 8%.

Given the events of the past eight months and Mercury's growth, all of these business lines have likely grown considerably. The recent VC banking feature set could be especially interesting, unlocking a new swathe of deposits.

While Mercury will be happy for the bounty high rates provide, they're not strictly positive for the firm. For one thing, high rates pressure other players in the banking market. While Mercury could benefit from the weakness of rivals, frailty in the broader ecosystem could create lose-lose dynamics. As we’ll discuss in greater detail shortly, no one is likely to benefit from a broad sectoral crash.

Moreover, lower rate environments benefitted risk-on asset classes like venture capital and the startups they finance. As Kang noted, if rates decline in the near future, that could benefit Mercury. "That would improve the top of the funnel," he said.

There are perhaps few better signs of a resilient business model – Mercury is a company that is almost financially self-balancing, able to thrive in different environments. As we'll discuss shortly, it may be able to layer on high-margin SaaS revenue to its current mix.

Culture: Productive obsession

Customer obsession is a trait every business should aspire to, but few achieve. Mercury is one such exception. At the heart of its culture is a desire to put the user first. This focus starts with leadership.

Farsighted leadership

In Immad Akhund, Mercury possesses an experienced, thoughtful CEO building his life's work. Akhund has seen Mercury as a multi-decade project from the beginning, allowing him to think on long-term horizons.

It's a trait readily apparent to the company's investors. "This is a business he wants to build for a long time, so he acts accordingly," Saar Gur remarked. The CRV GP pointed to Akhund's handling of the last bull run as an example of Akhund's farsightedness. "When the market was ripping, he didn't go crazy," Saar Gur remarked. Even as the fervor pressured founders to raise more money, hire larger teams, Akhund didn't over-extend the business. "He's his own man," Gur said. "He's going to reach his own conclusions."

The SVB debacle offers another example of Akhund's shrewdness and patience. While a more short-term-minded CEO might have taken to opportunistic tweeting to drive more inbound business, Akhund focused on serving customers and shipping greater protections. When I caught up with Akhund just days after the SVB devastation, he remained remarkably levelheaded despite the fatigue the most dramatic, frenetic week in his company's history must have invited.

Akhund's calm should not be mistaken for passivity. One of the CEO's strengths seems to be identifying opportunities and executing against them relentlessly. "The fearlessness with which he talks about attacking big product markets is impressive," Michael Gilroy said. "He'll say, 'We're going to launch venture debt, we're going to launch a credit card.' There are entire companies raising money on those theses alone. He talks about them as if they were just features."

Head of Banking Partnerships Catherine Ordeman seconded that assessment. "You come to Immad with any idea and his response will be, '10x it.'"

Mercury CTO Max Tagher shares Akhund's trademark thoughtfulness. "Every interaction with him feels meaningful and intentional," Ordeman said. "You'll ask him how he's doing and he'll give this very considered, honest answer. No question is a throwaway question for Max."

Tagher brings that first principles thinking to his work at Mercury. That includes the coding language in which the platform's back-end has been built: Haskell. Though often viewed as an academic language, using Haskell has benefitted Mercury. According to Tagher, Haskell invites fewer runtime errors than Ruby on Rails and excels at data modeling. Though an esoteric choice, it demonstrates Tagher and Co.'s willingness to choose the best possible solution to a problem, even if it is unorthodox. "Quality, in general, is a pretty important part of Mercury's culture," Tagher remarked; Haskell is a critical component.

Beyond its technical benefits, using Haskell has proved a boon from a hiring perspective. "It's ended up helping with recruiting," Tagher said. "Lots of really strong developers want to use it." As one of the few startups leveraging the language, Mercury has established itself as a destination for Haskell obsessives. Indeed, two of the company's engineers have written books on the language.

Jason Zhang completes Mercury's founding trio. According to many at the company, the COO shines at building culture and fostering camaraderie. "He cares deeply about the people that work here," Ordeman remarked. "He wants it to be a place where people are happy."

Many of Mercury's traditions stem from Zhang. His fascinations with tea and pottery have become part of the company's character, with many appreciating herbal blends and beautifully-made ceramics. "He loves those things, and we end up loving them, too," Ordeman said. "Things like tea are ingrained in our culture," she added.

Dan Kang highlighted Zhang's contributions in this area: "He's done a great job building a unique culture." Beyond sharing his esoteric interests, Zhang also started the practice of giving every employee a "call sign," a nickname that can be used by others in the company and that comes with a custom emoji. Though it may sound gimmicky to some, it's become a bonding method. When an employee announces good news, for example, the Slack channels come alive with their call sign and custom emoji. "Jason is good at legend-building," Kang said.

Though each has different strengths and areas of focus, there's a kindred spirit across Mercury's executives. This is not a business run by a trio of fast-talking sales experts; it's a company devised by thinkers and built by craftspeople. Thought and care go into every decision, from the coding language to emoji selection. "Being human and thoughtful about little interactions…those things scale over time," Kang remarked.

Helpfulness and humility

Akhund, Tagher, and Zhang have created a culture oriented around customer obsession, helpfulness, collaboration, and humility.

We have already spoken about Mercury's customer obsession. Its second most pronounced value is helpfulness. Mercury employees are expected to pitch in whenever a customer or colleague needs assistance.

Akhund models this behavior by publicly responding to customer tweets, similarly to Patrick Collison at Stripe. Internally, employees enjoy knowing they can rely on one another. "I can ask anyone for help," Ordeman said. "And I know they will think through the problem and thoughtfully respond."

Beyond simply responding to one-off requests, this willingness to assist contributes to an environment many describe as collaborative. "Mercury really stands out in terms of how team-oriented and collaborative it is," Dan Kang said. "Every single team feels integral. They understand how they're contributing."

This collaborative atmosphere is even apparent to outsiders. Michael Gilroy remarked that Mercury's board meetings are uncommonly open. "Sometimes it feels like a product jam," he said.

Such helpfulness and cooperation could not exist without humility. Those who believe they are above the problem are perhaps least likely to help solve it. As a result, Mercury aggressively selects for team members with low egos. "The hardest thing to do is hire humble people," Akhund said. "But you want people that realize they have something to learn."

With plenty more to build, Mercury must ensure it retains a team humble enough to know it does not have all the answers but helpful enough to want to find them.

Risks: Black swan regatta?

If building a startup can be compared to a chess match, the last few weeks have seen the board reconfigured, the pieces moved. Less than a month ago, many would have considered it inconceivable Silicon Valley Bank could collapse. Though its troubles were better known, many still would have scoffed at the notion of a Credit Suisse forced sale. Both have, of course, happened.

All of which is to say that these are strange times for the financial world, and as a banking platform, Mercury may find itself exposed to macro-level turmoil. At the same time as it navigates a tricky environment, Akhund's company may also want to keep an eye on its competition.

Game of Fintechs

Mercury faces competition from fellow insurgents, platforms, and incumbents.

Mercury will want to pay closest attention to other well-capitalized insurgents with designs on B2B fintech domination. One investor described this landscape as a "very interesting Game of Thrones." "House Gusto, "House Rippling," "House Navan," "House Brex," and "House Ramp" are all formidable players that indirectly compete with Mercury.

Many are better known for products other than business banking, at the moment. Gusto leads with payroll services; Navan is a corporate travel platform; Brex and Ramp established themselves as corporate card companies.

But there's a steady convergence at work. These companies want to serve as a business's primary financial provider. All want to use their foothold to sell additional products and extend their customer relationship. And none can be taken lightly. Unlike the industry's incumbents, these startups are innovative and understand how to build attractive, modern products. Direct competitors like Rho and Novo also share these traits and cannot be counted out.

Though also technologically savvy, platform businesses like Shopify, Square, and perhaps, someday, Substack, represent a slightly different threat. Users rely on products to attract customers, process payments, and holistically manage their business. Because they're a part of capital flows, it's natural for them to offer banking services. Indeed, both Square and Shopify do so. Ultimately, Mercury will hope that big platforms have other focus areas and are happy to win over a relatively small customer subset with its banking offerings.

Though one of Mercury's largest incumbent rivals has just crumpled, there are other players. That includes megabanks like JP Morgan Chase, Capital One, Bank of America, and Wells Fargo. While these institutions might not be as tech-savvy as the startups listed, they have mass-market recognition and are often seen as the safer choice. Customers may find their size especially compelling in light of SVB's downfall; in a sectoral storm, blue-chip players like JP Morgan are safe harbors, perceived as the least likely to disintegrate. Mercury must find ways to win over increasingly risk-sensitive customers; its Vault offering is a good addition.

While every company should have a degree of competitive awareness, Mercury shouldn't spend much time fretting about its rivals. Business banking is a massive market, large enough to sustain multiple winners. According to an October 2022 report from Michael Gilroy (admittedly out of date given recent events), the public financial services market cap is pegged at $11 trillion – $5 trillion of which was created in the past 11 years. Gross profit pools for financial services were estimated at $6.5 trillion, exceeding healthcare ($4.8 trillion), e-commerce ($1.9 trillion), and software ($700 million). Such enormous sums give Mercury plenty of room to operate.

Moreover, very little of the financial services industry has been penetrated by fintech. That's somewhat surprising given how aggressively venture capital firms have invested in the space, less so when considering the number of large incumbent banks and the time it takes to build share in the space. By Coatue's estimates, modern fintechs hold just 2% of public financial services market cap.

Crash test

One of social media's underrated gifts is how effortlessly it seems to spawn experts. When a war breaks out, Twitter is suddenly rife with military commanders. A free speech dilemma embroils the nation; a hundred thousand constitutional lawyers manifest. A meme stock takes flight, and a million investing experts are born as it climbs.

The past few weeks' events have created a new genesis: macroeconomics savants. Social and traditional media outlets have hosted a spectrum of opinions on the current economic crisis ranging from alarmist to nonchalant. Depending on what you consume, the Federal Reserve acted shrewdly or moronically by hiking rates last Wednesday; the risk of inflation outweighs the possibility of a widespread banking crash or doesn't; we are in the midst of a "slow-rolling crisis," or SVB was "just a blip."

If "real knowledge is to know the extent of one's ignorance," as Confucious reportedly said, I am happy to be (briefly) among the knowing. I cannot add any textured, original analysis to the current macroeconomic environment, nor would such a discussion fit neatly within the confines of a company case study.

For the sake of this conversation, it is sufficient to say the banking system is undergoing significant stress that is likely to increase as the Fed attempts to thwart inflation. Faith in these institutions is declining, along with their stock prices. Several banks have already failed (or narrowly avoided disaster); more may come. As a business built on partner banks, Mercury would be especially vulnerable to a widespread collapse – even if it might be better positioned because of its distributed approach.

Assessing a startup's prospects in the face of a black swan event (or, perhaps, a series of them) is a strange exercise. Who wins in a catastrophe? How do you predict the fortunes of one small business amidst an unimaginable tempest? By definition, these cataclysmic events manifest unpredictably and tower above people, companies, and even nations. The fate of one tech company pales in comparison; a palm tree staring down a tidal wave.

Would any young company thrive amidst a widespread banking crash? How can you tell which founder would survive a prolonged, barren depression? As one investor put it, "The only startups that would be working in that kind of environment would be those selling guns and ammo."

If SVB's disease proves broadly contagious, it would be bad news for Mercury – and many others.

Future: The new standard

Though Mercury will be mindful of its risks, it has many reasons to be optimistic. As noted, the firm is in rude health, growing at an unprecedented clip, and shipping innovative products.

Over the next couple of years, Akhund and his team have a rare opportunity: to become Silicon Valley's new standard. It must launch new products, experiment with a different business model, and potentially vertically integrate.

Cosmic cube

When Immad Akhund pictures Mercury's future, he envisions a "cosmic cube." In simple terms, the CEO wants the business to grow along three dimensions that make up the cube's axes:

X-axis: Different verticals. Today, Mercury focuses on VC-backed startups, e-commerce companies, and venture capital firms. Over time, Akhund wants to deepen its share in verticals like web3 startups, consulting firms, and real estate agencies.

Y-axis: Different core products. As we've discussed, Mercury offers primitives like a bank account, venture debt product, credit card program, and treasury services. As well as building fresh core products for its existing verticals, Mercury will build features for the new verticals it pursues.

Z-axis: Improving quality. Akhund admits this is a more abstract goal, but it remains important to Mercury. Mercury must also improve its fundamental functionality as it extends its scope, becoming more reliable, better protected, and easier to use. This is a never-ending quest.

The abundance of opportunities Mercury has becomes clear when viewed through this lens. Indeed, it is arguably one of the company's most pronounced risks – there's so much you could feasibly build that prioritization becomes a genuine challenge.

Though gloomy, one source of guidance is Silicon Valley Bank. Mercury can pick through the defunct organization's playbook and strategically build alternatives to its most valuable, lucrative product lines.

One compelling play would be for Mercury to move beyond the business and serve the business person, launching a wealth management solution. The average startup founder or employee is not well-served by existing banks, who often don't understand how to leverage or manage stakes in valuable private companies. Startups like Compound have attracted attention for their tailored services; SVB's wealth management division managed $16 billion before its fallout.

SaaS upside

Mercury is already a software platform financial operation teams use and love. Why not leverage that relationship to build a subscription product?

VP of Finance Dan Kang discussed the possibility, emphasizing the importance of getting it right. "What I don't want us to do is tack on a monthly fee and call it SaaS," he said. "But there's so much value we can drive when it comes to workflow automation for accounting and finance teams. We want to give them back time."

As mentioned, Mercury already has some useful tools baked into its platform for free, but it's not hard to imagine how it could supercharge these efforts.

One place to start would be by increasing the financial visibility. While Mercury does support integrations, it could widen its range, making it easy for customers to view their comprehensive financial health across bank accounts, payments providers, databases, and ERPs. Mercury could leverage this improved visibility to better address reconciliation and provide more robust automations between accounts and platforms.

Ultimately, Mercury has the opportunity to become the source of financial truth for the startup ecosystem. That could turn the banking platform into a SaaS machine if correctly executed.

Becoming a bank

Earlier in this piece, we outlined why few fintechs try to build a bank. The costs are too high, and the risks too steep. And yet, despite the downsides, Mercury may one day decide to do exactly that, vertically integrating to become a fully-fledged bank.

Why would Immad Akhund want to do this?

Firstly, it would give Mercury total control over its customers' experience. Though the startup has worked well with partners, creating an innovative, delightful experience, it has inevitably had its possibilities curbed by relying on external parties. Bringing the entire process in-house would unlock new product opportunities and allow Mercury to improve its exceptional service.

Secondly, it would give Mercury autonomy over risk management – a shift that could cut both ways. On the one hand, Mercury could decide how it managed its asset base, removing the possibility of suffering because of another institution's incompetence. On the other hand, risk management is not easy, and even well-run firms can make mistakes. Moreover, shifting to a vertically integrated approach would conflict with the sweep network, which helps distribute risk at the moment. Mercury would need to develop new core competencies to excel at this function.

Finally, by cutting out partners, Mercury would improve its economics. Rather than splitting fees with collaborators, Mercury would earn them outright. Ultimately, internalizing all banking functionality would be a significant move for Mercury and one that is unlikely to arrive anytime soon. But even for a business based on a partner model, it is not an impossibility.

My last conversation with Immad Akhund before this piece's publication occurred on March 17. Despite the frantic week he had just endured, Mercury's CEO sounded ready for whatever 2023 might bring. "I think the world will change dramatically, and our understanding of things will change dramatically in the next few weeks."

Akhund's hunch has proven correct. Since that conversation took place, UBS took over Credit Suisse, the Fed hiked rates, and fears about a sectoral contagion escalated. And, of course, Mercury kept shipping, launching its VC banking product.

"One of the benefits of being a startup is that we can be nimble. We don't have to be too stuck on one course," Akhund said. "And so we're going to prepare ourselves and have the mindset of building what our customers are looking for." Even when chaos is reigning, the desire to better serve customers should stand Mercury in good stead.

*Mercury Treasury is offered by Mercury Advisory, LLC, an SEC-registered investment adviser. Registration with the SEC does not imply a certain level of skill or training. SEC registration does not mean the SEC has approved of the services of the investment adviser. This communication does not constitute an offer to sell or the solicitation of any offer to purchase an interest in any of the Mercury Advisory, LLC investments or accounts described herein. No representation is made that any investment will or is likely to achieve its objectives or that any investor will or is likely to achieve results comparable to those shown. Past performance is not indicative, and is no guarantee, of future results. Mercury Treasury is not insured by the FDIC. Mercury Treasury are not deposits or other obligations of Choice Financial Group or Evolve Bank & Trust, and are not guaranteed by Choice Financial Group or Evolve Bank & Trust. Mercury Treasury products are subject to investment risks, including possible loss of the principal invested. Some of the data contained in this message was obtained from sources believed to be accurate but has not been independently verified. Please see full disclosures at mercury.com/treasury.

**The IO Card is issued by Patriot Bank, Member FDIC, pursuant to a license from Mastercard.

The Generalist’s work is provided for informational purposes only and should not be construed as legal, business, investment, or tax advice. You should always do your own research and consult advisors on these subjects. Our work may feature entities in which Generalist Capital, LLC or the author has invested.