Plaid: Finance's Next Great Network

After turning down Visa, the $13.4 billion fintech is thriving solo. It’s become a true multi-product company with room to run.

The Generalist delivers in-depth analysis and insights on the world's most successful companies, executives, and technologies. Join us to make sure you don’t miss our next Sunday briefing.

Supported by Plaid

Partners like Plaid make it possible for The Generalist to deliver deeply researched case studies to readers like you, for free. We’re grateful for their support and encourage you to learn more about their business.

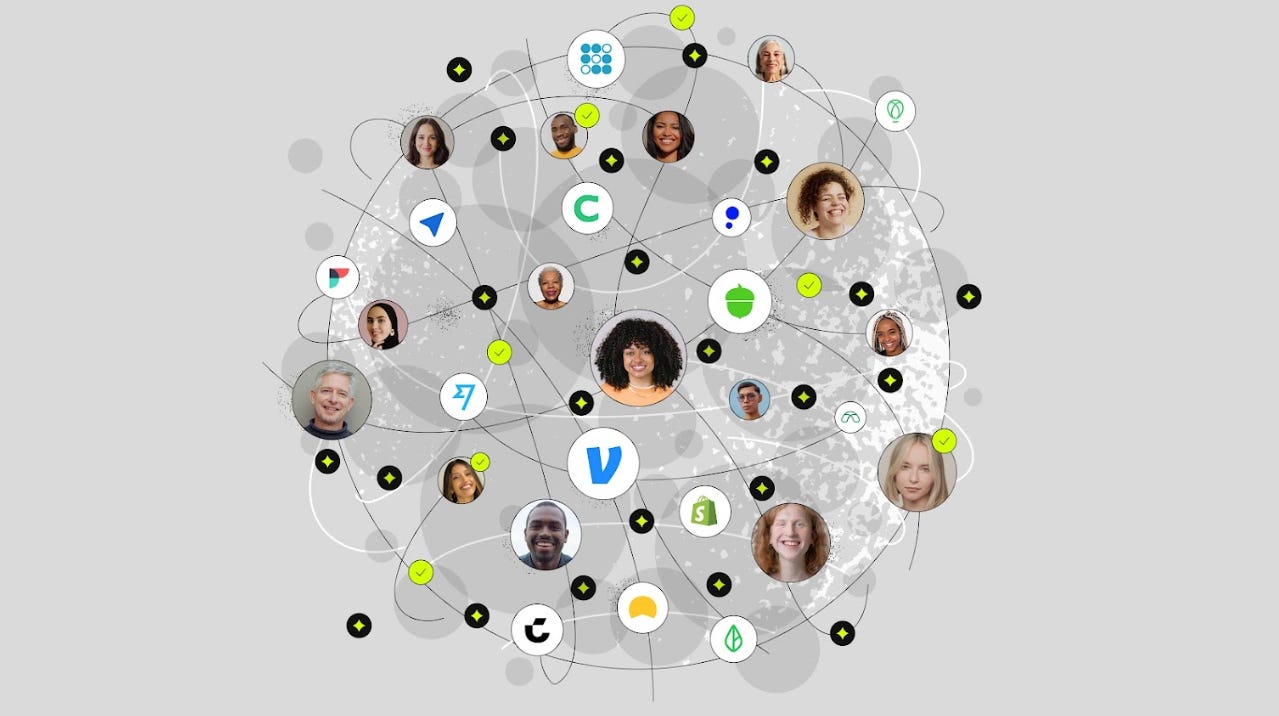

Plaid is a cutting-edge data network that makes it easy and safe to build financial services that drive better outcomes for consumers. It powers tools that millions of us use every day to live healthier financial lives. Venmo, SoFi, Etsy, Rivian, Chime, and thousands of other companies rely on it to provide their products. You can learn more about Plaid’s powerful and growing network, here.

Actionable insights

If you only have a few minutes to spare, here’s what investors, operators, and founders should know about Plaid.

From API to network. Plaid is best known as a provider of financial data APIs. That view is increasingly outdated. Over the past few years, the fintech has rolled out a suite of robust products spanning identity verification, payments, credit, and beyond. Its reported $250 million acquisition of Cognito in 2022 has proved particularly helpful in Plaid’s identity and fraud prevention push.

Beyond fintechs. Venmo was famously Plaid’s first customer. The payment app’s interest was the first of many, with thousands of fintech startups turning to Zach Perret’s infrastructure firm. Though Plaid is still the de facto choice for small tech-savvy players, its aperture has grown. Today, Plaid’s customers include big banks, industrial firms, e-commerce platforms, and car companies. As of 2022, more than 50% come from outside consumer fintech.

International ambitions. Though still focused on the US market, Plaid is now available in 17 countries. It’s making a particularly strong push to win Europe, which has quickly become its fastest-growing market. In doing so, it faces a new competitive set and a very different regulatory landscape.

A changing landscape. The American payments landscape is in a state of flux. New rails like FedNow and RTP offer instant transactions, threatening the hegemony of ACH. Given that much of Plaid’s product is built around ACH, this shift could pose a threat. Plaid will need to adapt and embrace these new networks to ensure it is not left behind. Its recent product launches suggest it’s more than ready to do so.

Room to run. Venture capital has flocked to fintech in recent years. The buzz around the sector can sometimes disguise how early we may be in the fintech revolution. By some measures, fintechs account for just 2% of the $12.5 trillion in global financial services revenue, a percentage expected to grow rapidly in the coming years. As the apex connector in the ecosystem, Plaid is positioned to benefit from sectoral tailwinds.

This piece was written as part of The Generalist’s partner program. You can read about our ethical guidelines in the link above. We always note partnerships transparently, only share our genuine opinion and commit to working with organizations we consider exceptional. Plaid is one of them.

In January 2021, Zach Perret invited his company’s leadership team to his home in San Francisco. It was time to make a decision.

For the past year, Perret’s fintech Plaid had focused on finalizing its merger with Visa. The mammoth payment network had offered to buy the startup for $5.3 billion in late 2019. It had seemed a clear win/win at the time. Not only did Visa’s offer promise a massive windfall for Plaid’s employees and investors, it provided the access and credibility to radically accelerate their trajectory. Meanwhile, Visa looked set to secure one of fintech’s best-positioned firms with a talent base long-time investors considered remarkable.

A year is a long time for any startup, but 2020, at Plaid, was especially eventful. Like the rest of the business world, the pandemic forced the company to adapt its operations, shifting to a fully remote structure. Covid’s greater impact, however, was on Plaid’s customer base. As physical branches shuttered, all essential banking activity moved online. In tandem, a scorching bull market sparked widespread interest in retail investing. An unprecedented eruption swept the fintech sector as consumers flocked to new, tech-first products. Though companies like Robinhood and Coinbase may have earned the headlines, Plaid was the quiet winner, its financial infrastructure subtly powering the revolution.

Toward the end of 2020, Zach Perret began to ask himself: did it still make sense to sell to Visa? It was not a simple question to answer. On the one hand, the synergies between the two companies were significant. Indeed, Perret had already witnessed the impact of being associated with Visa; even though the acquisition had yet to close, its promise had given Plaid new credibility with banking’s biggest players. Doors that had once looked closed opened before his young firm.

On the other, Plaid was no longer the same company it had been 12 months earlier. Covid had acted as a “huge inflection point,” in Perret’s view, and his firm had the traction to show for it. Along with its astonishing growth rate, the past year has also demonstrated Plaid’s importance and influence in the financial firmament. Five-point-three billion dollars had once seemed like a good price; it was beginning to look too much like a bargain. That the Department of Justice looked set to complicate the merger didn’t help matters.

And so, Perret called a meeting to make a final, multi-billion dollar decision. Would Plaid proceed with the acquisition or recommit itself to life as an independent business?

There was some symmetry in Perret’s choice of venue. The decision to sell a year earlier had been made in his living room, with leadership congregating at his house over a December weekend to avoid disrupting the broader workforce. Perret’s home now served as a meeting point again, albeit in a somewhat altered configuration. With Covid precautions still in effect, Plaid’s leadership spread across the room. Some even sat outside, beyond a set of open patio doors.

Over that day, Plaid’s leadership assessed the different options – and the risks that came with them. What would it mean to walk away from the deal? How would employees that had expected a significant payout feel about the volte-face? Could the company rebuild the parts of the team it had deprioritized in preparation for a merger?

Despite the inevitable complications, the more leadership talked, the clearer the decision became. Plaid’s potential had meaningfully grown in the past year, and the team was keen to fulfill it as a standalone business. Perret’s choice was made: Plaid would stay an independent company. It was, in spirit, a second founding, a group of operators electing to remain in the arena.

With the benefit of two-and-a-half years since that decision, we can see what Plaid has done with its second lease of life. More impressive than the $13.4 billion valuation it secured shortly after walking away from the Visa deal is the manner in which the firm has expanded its aperture.

For much of its life, Plaid was defined by its extraordinary first product: an API that made it easy for financial products to connect to a consumer’s bank account. That may still be the prevailing image for many, though it’s increasingly outdated. Over the past few years, Plaid has aggressively pushed into adjacent areas, including identity verification, fraud prevention, payments, and assets and income verification for lenders. As well as becoming a true multi-product business, these forays have strengthened the firm’s core strategic advantages and further differentiated it. Plaid has the makings of a generational financial platform with enduring network effects. If well managed, Plaid could be a long-term compounder, growing for years to come.

For that to happen, Perret’s company must continue investing in innovation, pushing forward on its recent initiatives, and finding fresh ways to bring value to its customer base. It must do so at a time when the broader American financial system is in a state of flux. Recently launched payment networks like FedNow may alter how money moves in the US, posing new challenges and opportunities. Ultimately, as more financial interactions move online, few businesses are better positioned than Plaid.

This is a portrait of a company that shook up the banking industry, laid the groundwork for the fintech renaissance, walked away from $5.3 billion, and has designs on becoming the next great network for all online financial activities.

Origins: A long climb

“First they ignore you, then they laugh at you, then they fight you, then you win.” That quote, usually misattributed to Mahatma Gandhi, is an apt summation of Plaid’s journey. From the perspective of the financial world’s big players, the startup has evolved from an irrelevance to a pest to an existential threat to a pivotal partner.

Rites of passage

Every management consultant worth their salt must be in possession of a few essential items. The non-negotiable tools of the trade: a stack of starched button-downs, fluency with business lingo, a ready smile, a penchant for “back of the envelope” calculations, and, above all, facility with the Microsoft Office Suite.

In 2011, at Bain & Company’s Atlanta offices, Zach Perret inducted William Hockey into this class of business magi, teaching him the basics of Microsoft Excel. It is funny to imagine this as the introduction for one of fintech’s most quietly innovative founding pairs: a nondescript office room, a standard-issue laptop, a sea of blank spreadsheet cells.

Thankfully for modern financial consumers, that drab context didn’t dampen the immediate kinship between Perret and Hockey. While fumbling through a few macros, they discovered they were both software developers by training, agreeing that Python would be a much more efficient way of solving the tutorial they’d been tasked with. They also discovered a shared passion for climbing, which led to a perilous weekend excursion. While scaling a local rockface, Perret dropped Hockey twenty feet. Though it sounds like a lively anecdote today, it was a genuinely frightening moment that cemented the colleagues’ bond. “We became friends for life,” Perret said of the episode.

Beyond climbing and coding, the pair shared another interest – one that has united consultants for generations: the desire to leave consulting. Neither would make it to the standard two-year mark, decamping for New York City in 2011. They left Georgia with little plan other than to find their way into the more dynamic world of tech startups.

City of empires

It was not an easy transition, and in truth, New York City in 2011 was not the place to make it in tech. Though the city has seen a surge in activity and venture funding over the past few years, bringing it closer to parity with Silicon Valley, it lagged far behind in the early 2010s. Beyond Union Square Ventures, there were few active, early-stage franchises in the city and a paucity of successful startups from which to draw wisdom or talent. The year that Perret and Hockey moved, NYC-based startups attracted approximately $4 billion in venture funding; a decade later, volume would crest $29 billion.

What New York lacked in startup activity, it more than made up for in financial relevance. In 2011, the Occupy Wall Street movement consumed the city’s banking industry. After police booted protestors from Zuccotti Park in the financial district, they settled in Union Square, home to a workspace Perret and Hockey had found. It served as a provocative impetus, challenging the would-be operators to direct their attention toward an inadequate financial system needing new solutions.

As they searched for opportunities, Perret and Hockey decided to spend their free-time building better financial applications. Clearly, consumers weren’t being served by the status quo – could technology help make something better? On the heels of earning (and forgoing) their first full-time salary, it’s perhaps unsurprising that budgeting was a particular area of interest. Indeed, Perret had deliberately stayed at Bain long enough to receive his $4,000 bonus but quickly found it didn’t last long as a would-be entrepreneur in the city. In developing various side projects, the pair confronted a stubborn problem – and recognized an opportunity. To build a decent budgeting application, you need data from the consumer’s bank.

How else could you quantify and categorize a user’s spending? Despite its obvious utility, getting that information wasn’t easy. To do so, application builders like Hockey and Perret had to build bank integrations for each institution. If you wanted to serve Bank of America customers, you needed to build that integration; if you had users with Goldman Sachs accounts, you’d have to create that connection. This pattern repeated across the country’s tens of thousands of financial institutions.

To Perret and Hockey, this seemed like a mind-boggling inefficiency. It was, effectively, an operational tax on innovation. By Perret’s estimation, constructing the requisite connections absorbed “85% to 95%” of his and Hockey’s coding time, taking focus away from developing the budgeting app’s actual feature set. How could any small team get off the ground with such demands monopolizing bandwidth? A better system was needed, the pair agreed. Why shouldn’t they be the ones to build it?

The Venmo inflection

In early 2012, the former consultants decided to officially strike out on their own. They set about building a new banking infrastructure platform from their small Union Square office. They found an apt name for their company by staring at their whiteboard one day. Perret and Hockey wanted their startup to not only connect to banks but structure the information it received.

Review your monthly bank statement, and alongside familiar names, you’ll see strange strings of numbers and letters that don’t connote an obvious vendor. For financial applications, that represents a challenge. How can you help consumers understand their spending when you can’t be sure where their money is going? To try and decipher this code for the financial apps they hoped to serve, the founders “cross-compared” transactions, looking for similar locations or patterns. It produced a strange hatching when they mapped that process out on the board. Looking at it, one of them remarked that it looked like plaid fabric. After some research, they discovered the name was free of trademark squatters, and a dot-com domain was available for purchase. As Perret said, “the rest is history.”

That history might have been a short one were it not for Venmo. As Sam Lessin, General Partner at Slow Ventures and early-Venmo investor, alluded to in a recent interview, the peer-to-peer payments app holds an unusual position in tech’s recent history. Today, it is ubiquitous, achieving verb form, processing hundreds of billions of dollars in volume annually beneath PayPal’s umbrella. Yet, it was sold to Braintree for $26.3 million in 2012, a relative pittance, before Braintree was snapped up by PayPal for $800 million a few years later.

Around the time of Venmo’s initial acquisition, a friend at the company reached out to Perret and Hockey. The payments app sought a better way to connect to consumers’ banking accounts. Could they help?

It was an early inflection point. Signing Venmo validated the need for Plaid’s product and brought a wave of end-users through the door. Critically, it acted as an important proof point, too. A new generation of “fintech” companies had bubbled up in Venmo’s wake; those upstarts turned to Plaid to address their infrastructural problems.

False equivalencies

Perret and Hockey decided to head west to Silicon Valley in search of capital and talent. Despite their success in snagging Venmo as a customer, raising funding was far from easy. Indeed, what seems like an obvious opportunity today was viewed skeptically by yesteryear’s capitalists. In large part, that was a result of the sector’s history. While Perret and Hockey were right in noting that no one had adequately solved the problem of making bank data accessible to small startups, alternatives did exist. Yodlee, founded in 1999, was the space’s elder statesman.

While its team had succeeded in building a large, viable business, it hadn’t broken out to become a true tech giant. (It would eventually go public at a $340 million valuation in 2014, then sell to private equity for $660 million a year later.) For many venture capitalists, that suggested the market for Plaid was capped, incapable of delivering a multi-billion-dollar fund returner. By Perret’s count, at least fifty venture capitalists passed on investing in the startup’s seed.

These investors may have missed Plaid’s differentiated approach and the material changes in the market. In particular, Plaid made three very different decisions than many of the sectors precursor companies:

A new, growing market segment. Perret and Hockey fundamentally believed that technology would transform the financial system. In particular, they foresaw the rise of rich consumer fintech applications capable of taking action on behalf of the user – whether sending money or making an investment. The founders also expected financial transactions to “embed” themselves across the internet, showing up in e-commerce flows, home purchases, and car buying. Plaid would serve this tech-savvy customer base, growing along with it.

A different distribution channel. Bank connectivity providers typically sold top-down, leveraging dedicated sales teams. Plaid took a different approach. Rather than spending months selling to a senior buyer, it sought to win over developers with its superior API and clean documentation. Like Stripe, Plaid recognized that developers held the power when it came to tech startups.

A more flexible model. Providers like Yodlee favored long, annual contracts. While that made sense for a more mature client base and a more involved sales process, it wasn’t a fit for Plaid’s segment. The startup offered a usage-based approach to make it easy to get up and running with a more limited budget.

In sum, Plaid appeared to offer a superficially similar product to its predecessors but actually ran an entirely different playbook. Spark Capital recognized that promise, leading a $2.8 million seed round in the fall of 2013, with Google Ventures, Homebrew, NEA, and Felicis participating.

It wouldn’t take long for Plaid to raise its next round. In November of the next year, Perret and Hockey pulled in a $12.5 million Series A from inside investors. Within 18 months, Plaid had gone from a Sand Hill reject to a hot commodity.

Move fast and scrape things

As fintech bloomed, Plaid grew with it. But how, exactly, did Perret and Hockey’s product work? (For a theatrical, metaphorical explanation, you might enjoy a previous piece The Generalist published on the subject.)

In its early iterations, the startup relied on a data collection method called “screen scraping.” To bring bank account data into a fintech application, Plaid would receive credentials from the user, programmatically log in to their banking portal, and “scrape” relevant data like their account balance and recent transactions. Plaid would then ferry that information back to the fintech application to allow the consumer to use the application in question.

Plaid used this method as a matter of necessity. Fundamentally, screen scraping is a suboptimal way of collecting data. Small changes to the visual interface of the site being scraped can disrupt the process. Ensuring connections work requires significant upkeep and, thus, real cost. It’s also a relatively blunt tool, often extracting all data on a given screen – some of which consumers may not need to share. By comparison, API connections are much more reliable and targeted.

At the time, Perret and Hockey did not have the luxury of choice. Virtually no banks offered accessible APIs, making scraping the only viable way to serve consumers and connect their banking data with a growing wave of fintech apps. Years earlier, Yodlee had reached the same conclusion, building its business on the back of this methodology.

In those early days, the user experience of linking one’s account also differed from today. When Plaid’s customers implemented the service, they typically visually matched the account connection screen to the consumer’s designed bank. Plaid would later change this approach, highlighting its brand more visibly to emphasize its role in the connection process. (Class action plaintiff lawyers would later argue that because of this practice, some users were unaware that Plaid was involved in linking their accounts to an app they used. To avoid the costs of protracted litigation, Plaid paid a $58 million settlement. In agreeing to the settlement, the company explicitly refuted the claims and restated its commitment to consumer privacy. Today, the firm has some of the best user-facing privacy features on the market, which we’ll discuss shortly.)

Banks did not look kindly on this practice. Specifically, they resisted customers linking accounts to apps and services they could neither control nor oversee. That hostility was reflective of the skepticism with which industry heavyweights viewed fintech, putting Plaid into an adversarial position with key stakeholders. Perret’s firm wanted to connect to banks, but banks wanted very little to do with the upstart aggregator, uninterested in supporting digital use cases. However, as the company grew through 2014 and 2015, it became increasingly difficult to ignore.

Twenty-sixteen showcased banking’s animosity and Plaid’s growing influence. In April of that year, Jamie Dimon used his shareholders’ letter to warn against the specter of fintech applications and aggregators. The JPMorgan CEO shared his concerns about startups selling consumer data and introducing new risks. While some of these worries were legitimate (Yodlee, for example, purportedly sold consumer data to hedge funds), The New York Times’ coverage of the subject summarized the strategy behind the scaremongering: “Jamie Dimon Wants to Protect You From Innovative Startups.” Two years later, Capital One would go so far as to block third-parties from accessing Plaid, upsetting some of its customers.

Thankfully for Plaid, not all banks took such a dim view of innovation. A few months after Dimon’s letter, the company raised a $44 million Series B at a $225 million valuation. Crucially, the round was led by Goldman Sachs with participation from Citigroup and American Express’s venture arms. It had taken approximately four years, but Plaid had officially won the favor of some of Wall Street’s powerbrokers. Within another four, it would have a multi-billion acquisition offer on the table.

Tough choices

By the time Visa bid in late 2019, Plaid was a very different company. It had grown rapidly in the intervening period, hitting 10 million consumer account connections in 2017 and doubling to 20 million the following year. That growth was aided by the maturation of its customer set as users like Venmo and Chime reached a mass audience.

It had also raised more capital – and completed a purchase of its own. In 2018, Plaid closed a Series C co-led by Index Ventures and Kleiner Perkins. The $250 million round represented a huge markup from the 2016 investment, valuing Plaid at $2.4 billion. In the lead-up to the Series C closing, Plaid strengthened its position by acquiring a competitor: Quovo. Founded in 2013, Quovo had built a solid business serving the wealth management space, winning over customers like Wealthfront, Betterment, and Vanguard.

Though Quovo lagged behind Plaid, it was seen as something of an “ankle biter,” as Index General Partner Mark Goldberg noted. “In some ways, they were the cheaper alternative. They could exert pricing pressure and had very strong penetration in the wealth management vertical.” Indeed, when writing his investment memo before the Series C round, Goldberg cited Quovo as a key rival. To hear halfway through the process that Plaid was absorbing the firm was cause for celebration. “To get that call saying, ‘We’re buying Quovo.’ That was just fantastic.” Plaid onboarded a new customer base and fortified its position as fintech’s leading aggregator.

Plaid’s biggest shift came on the leadership front. In 2019, William Hockey decided to step back from the firm, leaving Perret to run it alone. It was a difficult change, per Plaid’s CEO. “That was a hard one for me,” he said. “Not because it wasn’t the right outcome for William or the right outcome for the business, but because William is one of my best friends.” At the core of the shift was Hockey’s realization that he enjoyed the early days of company building rather than the demands of scaling an organization. “He wasn’t having as much fun running a bigger company. He wanted to be at a small company – that’s what he loved the most. The thing was that I was going in the opposite direction: as the company got bigger, I had more fun.” When attempts to rework Hockey’s role and bring back some joy didn’t work, Hockey chose to set out on a new adventure.

Though Hockey’s departure didn’t disrupt Plaid’s operations, Perret felt his friend’s absence. “When it really set in 6 to 12 months later that I was the sole founder, then it felt lonely. The person that you used to talk to all the time isn’t there anymore. William and I still talk all the time, but he doesn’t have the same kind of context anymore – he wasn’t in the conversation that I was in yesterday.”

Hockey’s decampment meant that when Visa called in 2019, the final decision rested with Perret alone. The same was true a year later. Though Perret brought leadership into the process, hosting them at his San Francisco home, ultimately, the choice was his. With the benefit of hindsight, Perret believes both decisions – agreeing to Visa’s deal and then walking away from it were correct. “Visa offered us incredible opportunities to grow a lot faster and really internationalize in a big way,” Perret said of his initial rationale to sell. “They offered to fund us as an independent entity, so after going back and forth, we decided to sell. It was a difficult, emotionally-complex decision, but even with perfect hindsight, I believe it was the right decision at the time for the company to sell.”

A different calculation underwrote the 2021 reversal. “The prospects for us independently were much better: we’d benefitted hugely from Visa’s brand halo and the relationships we’d created, and our business had grown rapidly. And the reality was that the regulators had every intention of fighting the deal as hard as they could, even if I was optimistic it would close.” Perret summarized the ultimate rationale: “The main reason we walked away from the transaction was because the business was a fundamentally different business.”

Plaid’s existing investors supported the move. “There was a big sigh of relief and a lot of fist pumping and cheering at the Index office when we knew we were going to have an independent path,” General Partner Mark Goldberg recalled. “It’s going to take a lot longer, but I think Plaid is going to be a much bigger outcome.”

Just because it was the right decision did not make it easy. “It was the hardest year I’ve ever had in business,” Perret said of 2021. “There’s a lot of emotional complexity of saying to the team, ‘Hey, this thing we got you excited about [isn’t going to happen] and we need you to go with us.’” Landing that message would have been challenging at the best of times, but it was especially tricky given covid constraints.

In addition to reorienting company focus, Plaid also had to address structural gaps. “There were things we hadn’t done for a certain amount of time. For example, we hadn’t hired certain roles because we wouldn’t have needed them had the transaction closed,” Perret recalled. “We had to really quickly rebuild elements of the leadership team, we had to do this financing round because we had this big opportunity to raise additional capital, we started to scale up some of our new products – it was this crazy six month period at the start of 2021. It was the hardest period, not because the outcomes were bad – the outcomes were excellent – but because of the work we needed to do to get people running in the right direction again.”

Plaid experienced ridicule, rejection, animosity, and wild success in its first ten years of operations. It began its second decade as it had its first: standing on its own two feet, certain that the best was yet to come.

Product: The power of connections

Plaid is still largely known as a bank data API. Ask the average tech worker what Perret’s company does, and you’ll likely hear a description of that first product: Plaid is a business that helps consumers connect bank accounts to fintech apps. Though this is still true and an important part of Plaid’s business, it is no longer a sufficient explanation. As Matthew Sueoka, Head of Amex Ventures, noted, “A broader audience probably doesn’t understand the volume of use cases that are possible through the technology they have.” As mentioned earlier, Amex Ventures first invested in Plaid as part of the company’s Series B.

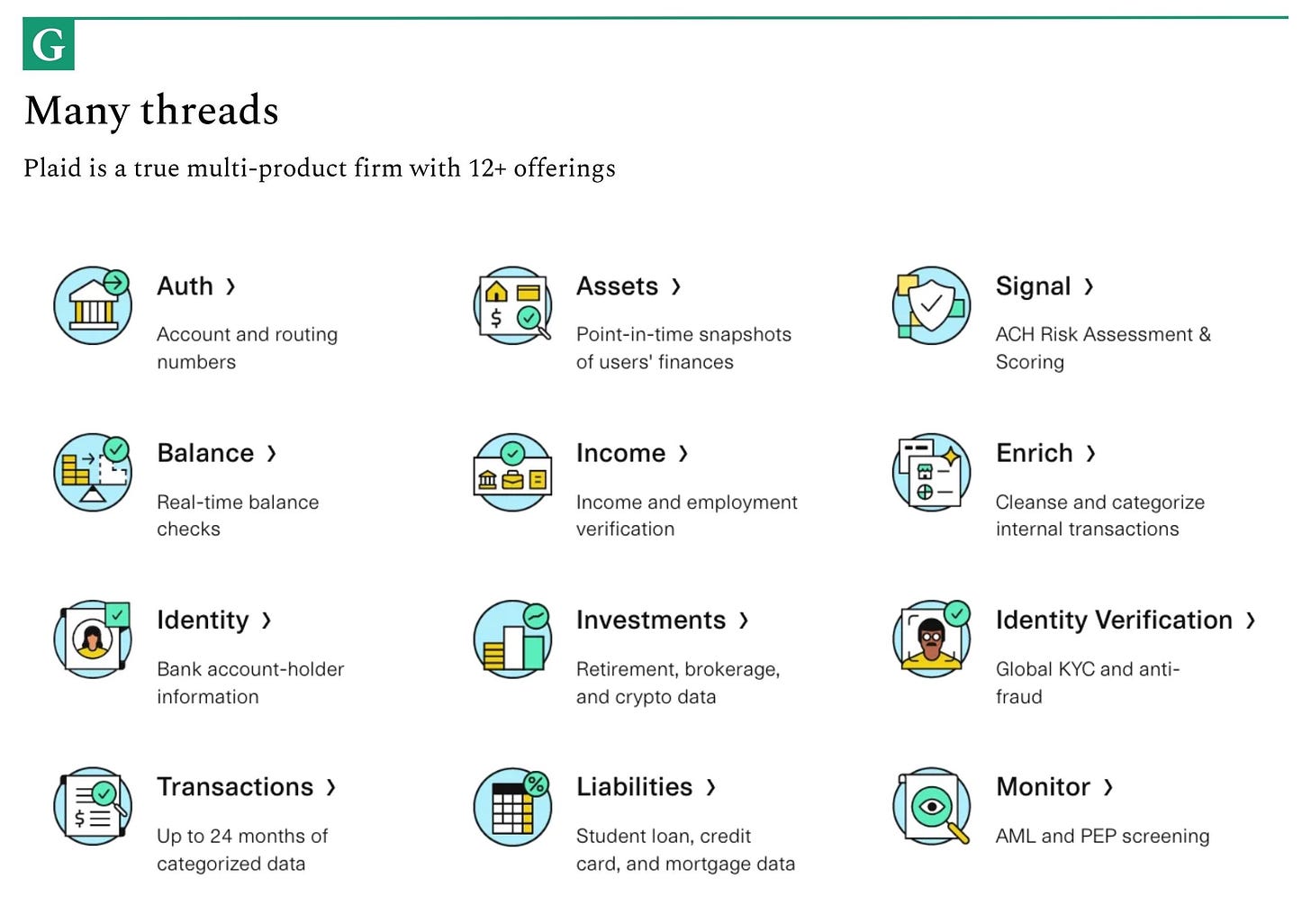

Over the past few years, the $13.4 billion firm has morphed into a multi-product business boasting a range of offerings. Indeed, Plaid’s range has grown so vast it can be difficult to get one’s arms around its sophisticated functionality at first blush. By our count, more than a dozen different products are available for developers.

Before jumping into a discussion about these products, it’s worth considering where Plaid sits among stakeholders. At a high level, Plaid is the central component of a three-sided marketplace between financial institutions, digital applications, and consumers.

Plaid knits together these different groups, piping data from financial institutions to digital applications, all to better serve the end consumer. Given the presence of these multiple stakeholders, it can be tricky to keep track of what we mean when we talk about Plaid’s “customer.” Though Plaid’s mission is to improve access for individual consumers, its true customers are digital application businesses. Companies like Chime, Venmo, Brex, and Wise pay for access to Plaid’s services, as do large banks like Royal Bank of Canada. Unless explicitly noted, when we talk about “customers,” you can assume we’re referring to this category. (We’ll refer to individual consumers as “users” or “consumers.”)

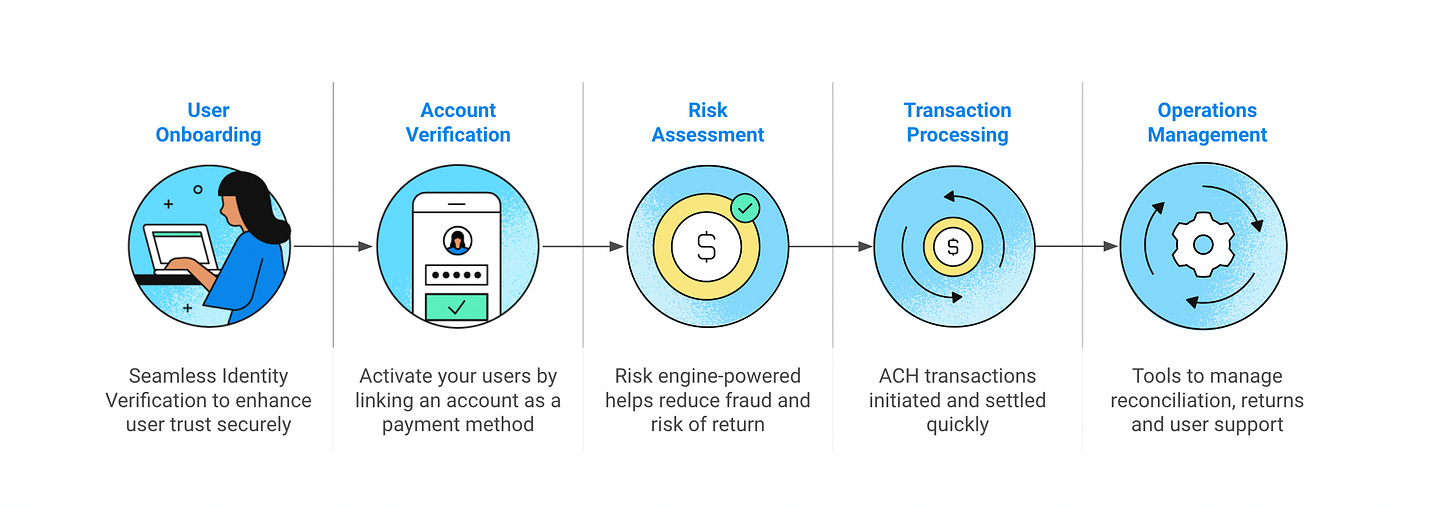

So, what exactly are Plaid’s services? What discrete products does it offer? Rather than reciting the features of each, we’ll focus on the problems Plaid solves for its customers. At a fundamental level, its suite is designed to do four things:

Onboard users

Manage risk and prevent fraud

Streamline payments

Improve credit decisioning

Though that may sound simple, doing it richly, reliably, and at scale takes extraordinary technological and operational skill.

Onboard users

Quite simply, Plaid is the best way to gather data on a consumer’s financial life. Its APIs retrieve varied data from banks and other financial institutions at a consumer’s request, porting data to financial apps. In that respect, Plaid acts as a data aqueduct, connecting different sources through a sprawling network.

Plaid delivers comprehensive data on user identity, bank balances, transaction history, income details, liabilities, and investments. Let’s walk through these.

Fintechs cannot properly serve a consumer unless they know who they are. When a consumer signs up for an app or service, Plaid makes it easy to collect user identity information from banking data, including the consumer’s name, phone number, email address, and so on. As discussed later, this information can be critical for fraud prevention and simplifying payments. It’s also essential to onboarding a user.

Once a consumer is onboarded, what should you let them do? For example, should you allow them to send a payment or not? A fintech or other application needs a person’s bank balance to answer that question. How much money is in their account at any given moment? Plaid collects and updates this data so customers don’t have to guess whether they should wave through a transaction or halt it. Access to this data reduces overdraft or “nonsufficient funds” fees for consumers. In short, it makes it simple for customers to offer a meaningfully better and cheaper service.

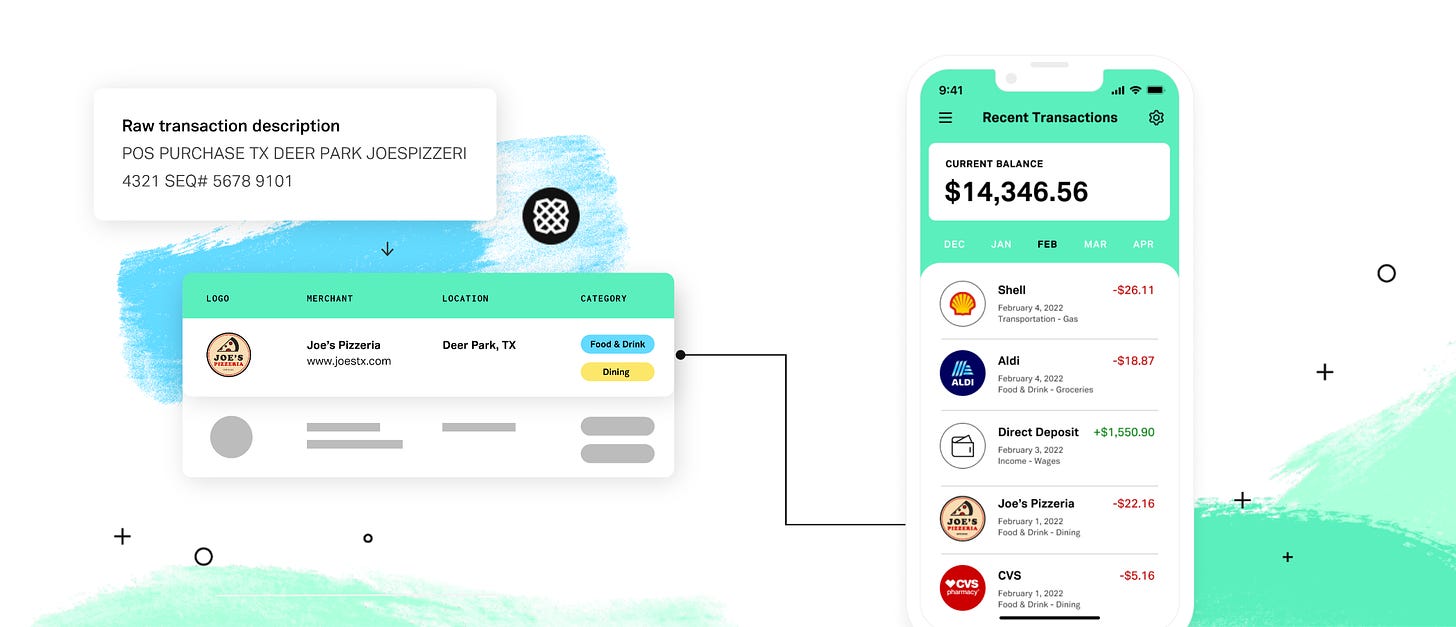

Just as knowing a user’s bank balance is important, so is understanding their transaction history. What are their spending patterns? How have they changed over time? Plaid can pull in up to 24 months of a user’s transaction data. This information is a source of truth on a consumer’s financial life and can be easily refreshed to stay up-to-date. Plaid also takes great pains to make this information as usable as possible, cleaning and enriching it by adding merchant, geolocation, and transaction details. This process turns an inscrutable string into a neat, legible transaction.

Doing so unlocks new opportunities for its customers. A fintech that knows where its users spend money can better provide cross-selling opportunities or make intelligent budgeting suggestions. Critically, data enrichment also reduces costly chargebacks, many of which occur because a consumer doesn’t recognize a given transaction.

Rocket Money CEO Haroon Mokhtarzada highlighted the consumer impact of this product in a conversation with Plaid COO Eric Sager. “We used the data that came in from Plaid and then built visualizations on top that helped people naturally make good decisions again with their money…It was the first time people could see a full list across all their accounts of where their money is going and what they’re paying for.” Such clarity and completeness wouldn’t have been possible without Plaid’s help.

Knowing a user’s income and employment status is another vital piece of data. Many major financial decisions, from mortgage payments to auto loans, rest on knowing how much someone earns. Traditionally, this data has been tricky to gather. Plaid has achieved nearly 100% of US workforce coverage by connecting to banks and payroll providers. (It also accepts manual uploads for edge cases.) Compared to outdated technological solutions or manual review, Plaid’s offering moves at lightspeed, with income verification occurring in an average of 11 seconds. The customer impact is profound: Purpose Financial, for example, saw its loan approval rate increase from 78% to 99.8% by embracing this product.

It’s worth noting what a promising space this is for Plaid. The past few years have seen multiple startups attract significant capital and high valuations to chase the payroll API opportunity. By muscling in, Plaid opens up billions in potential enterprise value.

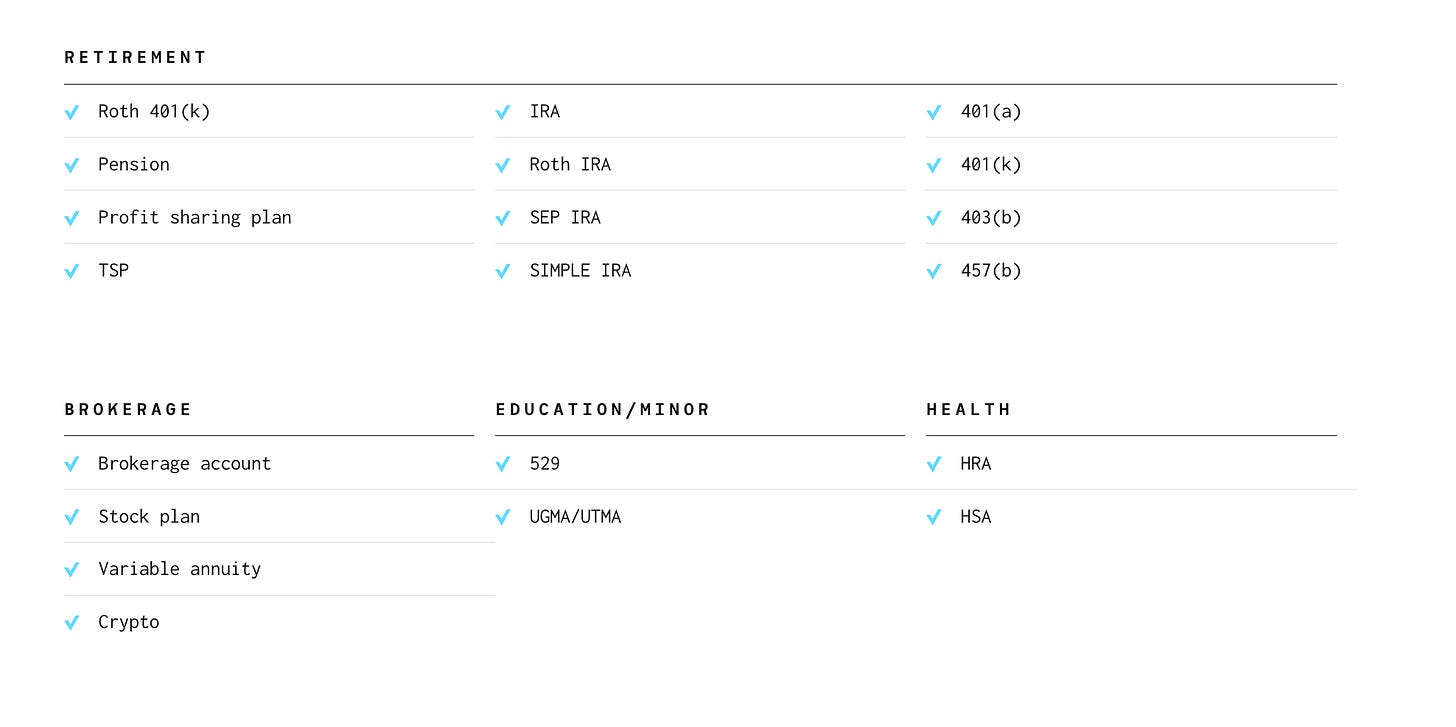

Income is an incomplete measure of a user’s net worth. Assets and liabilities are the final piece of the puzzle. Plaid connects to a panoply of different account types, covering 401ks, profit-sharing plans, crypto brokerages, and more, to get a good picture of a consumer’s investments.

It achieves a similar feat on the liability front through different connections, linking to student loan players like Great Lakes, Mohela, Navient, and FedLoan Servicing. It also pulls in detailed information on credit card debt and mortgages.

All told, Plaid has constructed a system to create a detailed picture of an individual’s financial life. Doing so has enabled thousands of financial applications to better guide and assist the consumers they serve.

Manage risk and prevent fraud

Plaid is not content simply acting as a data aggregator. It wants to help its customers (and their users) take action, making payments or accessing loans, for example. The company understands it cannot do this well without adequate protections. To that end, Plaid has invested heavily in building a best-in-class fraud detection and prevention suite. Its 2021 acquisition of Cognito for a reported $250 million has been pivotal in this process.

Shortly after meeting at Stanford, Alain Meier, John Backus, and Christopher Morton founded Cognito in 2013. With support from Y Combinator, the trio set about building a fraud prevention startup. The first version of the startup focused on “knowledge-based authentication” – the practice of asking users questions to determine their identity. If an onboarding process has required you to note the color of your car, select a street you once lived on, or report the name of your mortgage provider, you’re familiar with this methodology.

Though this route demonstrated some promise, it didn’t achieve an ironclad product market fit. “We had a product that was pretty good,” Meier recalled. “We got to $1 million a year in run rate, and we had something people wanted, but it wasn’t flying off the shelves. The market was getting hot, but we weren’t trending in the same direction. We had a lot of self-doubt and it forced us to go back to the drawing board and completely rebuild the product.”

The more Cognito’s founders thought about the traditional question-based form of authentication, the more flawed it began to seem. In the first years of selling that product, they’d learned that it was easier for fraudsters to answer those questions correctly than real users. “Fraudsters would just buy the answers online for a couple of bucks, whereas real people forget,” Meier said.

If Cognito was to differentiate itself from the market, it needed to develop a better, safer alternative. “We asked ourselves, ‘How can you make identity fundamentally more secure while also being lower friction?’ There’s this constant see-saw between the two. We ultimately landed on phone numbers.” Not only were phone numbers ubiquitous, but it was easy for a user to confirm their possession. “If you can connect someone’s phone number to their real-world identity, name, date of birth, address, and social security number, you can potentially ascertain who someone is and do it with less friction.”

It was an extremely smart shift, immediately resonating with fintech customers. “It took us two years to reach $1 million in run rate originally. With this new product, we did it in about three to six months.”

Despite raising little capital – just a $2.1 million seed round – Cognito was able to grow quickly, attract large fintech customers, and fortify its anti-fraud platform.

It looks like money very well spent. Meier now heads up Plaid’s Identity division, helping customers accept more good users and catch more bad ones. The company does this through identity verification, watchlist monitoring, and a new anti-fraud network.

As mentioned in the section above, banking data is one way to identify a user, but it is not the most robust method. In many instances, a more comprehensive assessment is required. Plaid offers three primary forms of identity verification of escalating fidelity. All assist in ensuring customers stay KYC compliant.

Review identity data. This is effectively the version described earlier. Plaid collects relevant information like name and phone number, then compares it with existing records and against regulated data sources. For quick, low-stakes activities, this verification may be sufficient.

Verify documentation. Plaid reviews state IDs, passports, and driver’s licenses, weeding out fake or out-of-date documentation.

Test “liveness.” For optimal verification, Plaid offers a “liveness” test. Using a smartphone or computer camera, Plaid scans an individual’s face ensuring that it matches their ID. Simply offering this step alone can be a powerful deterrent for fraudsters who do not want to show their face.

Beyond these three checks, Plaid also scans hundreds of attributes and signals to weed out bad actors, using data from its network, and behavioral analytics. This combination boasts stunning accuracy that far exceeds human detection. Meier shared an illustrative story: “We had an odd case where a customer came to us, asking why there was a partial match between a driver’s license photo and a selfie. They looked like completely different people, and they thought we had messed up. And so we dug into it, and it turned out that it was the same person after all – they’d just received extensive plastic surgery. The only part of their face that was the same was the eye region, so our engine determined that despite these changes, they were the same person.”

After identifying a user, Plaid helps customers ensure compliance by monitoring relevant databases. It regularly checks anti-money laundering (AML) and politically exposed person (PEP) lists, surfacing insights via an intuitive CRM. When necessary, customers have a straightforward way to review possible issues and handle investigations.

“Beacon” is Plaid’s newest fraud prevention play. At the company’s annual conference, Threads, Meier debuted this “anti-fraud consortium for fintechs and financial institutions.” The premise of Beacon is that coordination is the best defense against scammers. Plaid wants members of its new collective to share fraud information to stop further misdoings. By pooling insights, Meier believes each constituent member will be better equipped to stop bad actors and protect consumers from the ripple effects of a stolen identity.

It’s a compelling pitch that Plaid seems particularly well-positioned to make. It has all the requisite connections to surface relevant information where and when it’s most impactful. It’s early days for Beacon, but Meier already sees encouraging signs: “We’re going to all of Plaid’s top customers systematically and inviting them to join the network. The reception has been very good so far.”

Streamline payments

The information Plaid collects, and its protections, serve a goal: to make it easier to transact online. In particular, the company has developed architecture to streamline making bank-linked payments. Indeed, one of the reasons Visa was reportedly so interested in acquiring Plaid is that it saw it as a long-term threat to its card network. The fintech’s interbank connections positioned it to build an alternative that elided traditional card fees by using (and speeding up) ACH rails. If customers could make payments just as quickly but more economically, why wouldn’t they?

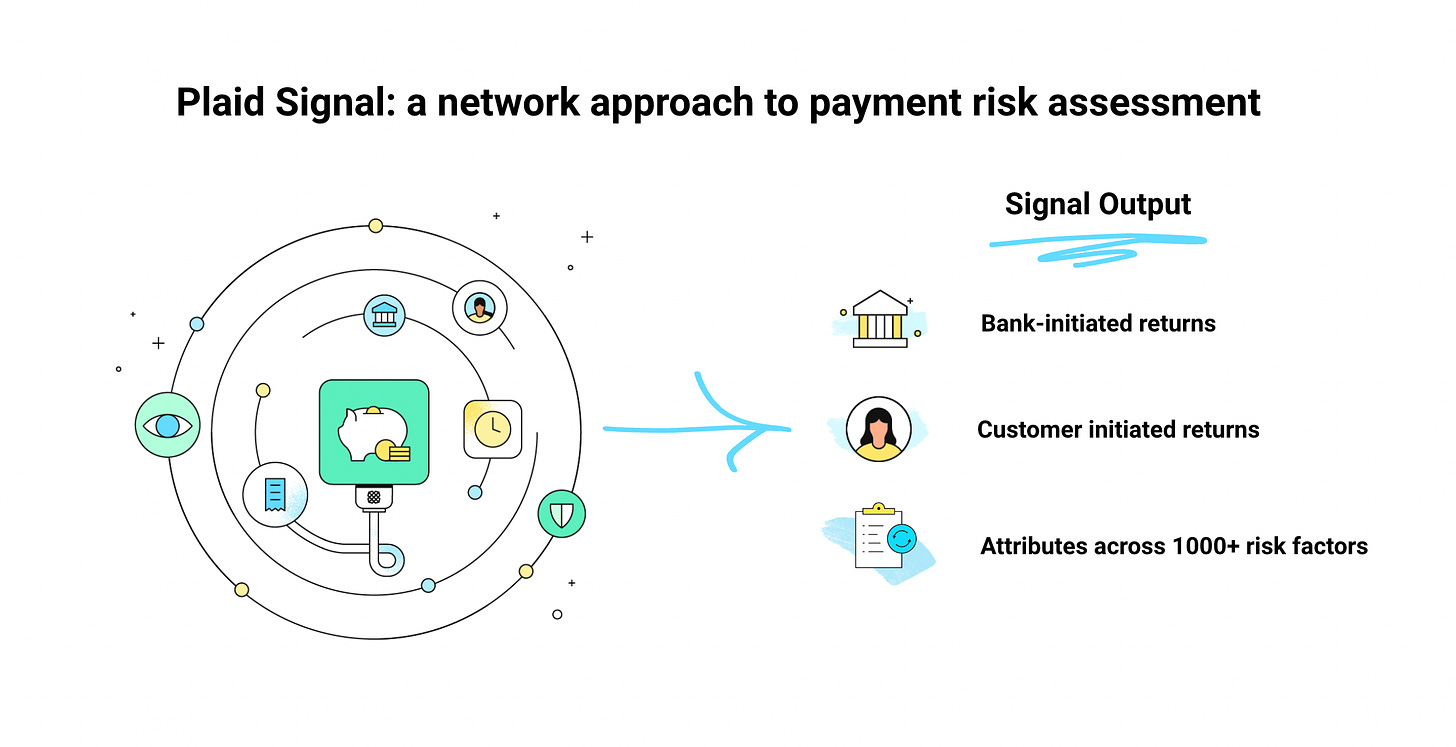

Over the past few years, Perret’s company has made significant strides toward this reality. Plaid works with a network of payment processors and offers a suite of APIs designed to accelerate, secure, and process payments. “Signal” is a recent innovation that is broadening the use of ACH among Plaid customers. Though technically a risk-scoring product, its impact on Plaid’s payments operations makes it more fitting to discuss it in this context.

Signal is designed to assess how likely an ACH transaction is to be returned. It does so by analyzing more than 1,000 disparate factors, distilling them down to 60 influential traits. Has the user connected with Plaid before? Have they made ACH payments previously? What does their cash flow history look like? Signal effectively answers these questions, and many others, to issue two scores representing the likelihood of a return:

Bank initiated. This score represents how likely the bank is to nix the transaction. Usually, this occurs because of insufficient funds or other administration returns.

Customer initiated. Though much rarer, customers also request returns, usually when transactions are fraudulent or have been unauthorized for some reason. Signal’s second score predicts the likelihood of this occurring.

Signal makes processing ACH payments radically simpler. If risk is low, payments can occur automatically, unlocking instant, safe ACH. Signal is reportedly processing more than $2.5 billion in monthly bank payments.

While the company has focused primarily on ACH, it is evolving. It recently launched a product called “Transfer,” which incorporates multiple payment rails, including the more modern “Real-Time Payments” (RTP) network and soon, FedNow. We’ll discuss this in greater detail below, but at a high level, it indicates Plaid’s desire to build a full-featured offering in the space.

Kraken is one of Plaid’s many contented customers. The crypto brokerage relies on the firm’s payment capabilities. “We’re incredibly happy with the service we’ve been provided through the Plaid team and we’re looking to expand that,” Kaushik Sthankiya, Global Head of Banking and Payments, remarked.

Improve credit decisioning

Credit is a more recent interest. As Perret remarked, Plaid entered the space after witnessing strong demand. “Those were dragged out of us by the market,” he said. “People were using our existing transactions product to do a bunch of analysis on a user and create an asset report. When we realized people were using it in this way, we thought, ‘Alright, maybe we should create a product for this.’”

Mike Saunders joined in April 2022 to head up the division, leaving a CEO role at fintech unicorn ZaloPay to do so. “The credit team is really part of this new generation of products at Plaid,” Saunders said. “I was super excited to join.”

As with payments, the data Plaid gathers through other products positions it perfectly to serve lenders. Historically, underwriting is a long, arduous process, with many players still relying on manual review. With Plaid, lenders can capture assets, liabilities, history, income, and more in a matter of seconds. Critically, this information is up-to-date, reflecting a real-time picture of a borrower’s financial circumstances rather than an outdated, point-in-time assessment. “There’s a lot of friction in the usual process and it’s really hard for a lender to get a holistic view of a customer,” Saunders said. Plaid’s product provides a smoother experience for consumers and customers and better data.

In just 18 months, Plaid’s credit services have seen an impressive uptick. “We’re working with a large number of customers across various segments,” Saunders reported. Among Plaid’s new customers is a large property management firm Saunders refers to as a “flagship.” In addition to its impact from a revenue perspective, the unnamed player is an interesting example of how Plaid has grown – not only has it extended its functionality, it has expanded its customer base. As we’ll discuss shortly, this is no longer a company selling solely to other fintechs.

Unlocks

Building a multi-product business is far from simple. Often, when companies attempt to add multiple new business lines, it can detract from or disguise the value of the core service rather than add to it.

When looking at Plaid’s collection of products holistically, it’s notable how strongly this is not the case. Instead, the different features combine to unlock new features and customer experiences.

For one thing, Plaid has built a rich end-to-end platform. When it first began life, Plaid’s role was relatively constrained: you connected your bank to the app you were using, and that was that. It was, in essence, a simple but effective data aggregator. Today, Plaid addresses multiple customer pain points, from user onboarding to transacting. Its value to its customer and the end consumer is continuous and multi-faceted.

Secondly, the firm’s different products appear to be composable and synergistic. Surf its website, and you’ll discover that one product is often built from several others. The new Transfer product is a good example of this bundling, unbundling, and rebundling. The beta service compresses user authorization, fraud scoring, and payment processing into a single API.

According to CTO Jean-Denis Greze, this structure is intentional. “Increasingly, we’re building a platform internally that makes it easier for our product teams to build new products faster than somebody else,” he said. That might be ensuring strong data science norms are followed so that future credit products have strong underlying scoring systems, for example. Ultimately, the aim is to create a structure that makes incremental innovation easier. “All these platform things make us faster. Whoever has more shots on goal and moves faster tends to win. So, how can we ensure we have more shots on goal?” As Plaid looks to extend its territory further, such flexibility will prove extremely valuable.

The synergy between products can be found at an even more granular level. For example, Plaid can use the information on file to autofill forms and streamline onboarding. Its “Remember Me” features for identity verification make it easy for consumers to get verified in a single click across Plaid-supported apps.

As this example suggests, Plaid has an unusually strong end-consumer relationship for a B2B banking infrastructure product. While the average American likely has never heard of Plaid, its ubiquity means it has stronger brand recognition than equivalent products. As customers connect accounts with Plaid, they build familiarity and trust with the company.

As Plaid continues to scale, the surface area for consumer interactions increases. Today, the company offers a “Plaid Portal” that allows individuals to manage their connections to various fintech apps. This product provides data transparency and puts control back in the hands of consumers. While this is far from a mainstream product, you can imagine a future in which it becomes a popular way to protect and modulate data sharing. Plaid can only offer a useful product here because of its ubiquity and brand. Though this attribute is relatively underdeveloped, it could be an intriguing space to watch in the coming years.

Model: Align and conquer

Plaid’s product evolution has established a business model with compounding power and growing reach. Before assessing the firm’s culture, it’s worth understanding how the fintech makes money, the intelligence of its approach, and the scale it has reached.

Usage-plus

Plaid has historically relied on a “sell through the basement” approach. It makes it easy for small companies to get up and running with strong self-serve functionality and generous free tiers. This approach allowed Plaid to win over budding fintechs and grow with them over time. Even though Plaid can serve many large businesses today (and does), it has kept this ethos. A new user today can get up and running with no monthly minimum spending.

When it comes time to charge, Plaid relies on three core models. Although there are subtle variations across the product stack, these are the fundamental approaches:

Per account charge. Some of Plaid’s products charge a one-time fee when an account is connected. For example, a customer that uses the Income API would pay for it just once rather than each time it is called.

Usage-based charge. Other Plaid APIs are priced per successful call. Every time a customer uses that product, they pay for it. The Transfer product relies on this approach, charging for each successful payment initiated.

Subscription fee. In some instances, Plaid charges a monthly subscription fee per connected account. The Liabilities” and Investments APIs incur this recurring charge.

Overall, Plaid’s model is nicely balanced. It aligns directly with customers (Plaid earns more when customers use it more) and benefits from a recurring revenue component. That second element could be critical in how the public market eventually values Plaid, allowing management to pitch the service as a quasi-SaaS play.

Though Plaid doesn’t share exact revenue figures, it has offered a few indications of its scale and traction. It boasts over 8,000 customers, and a third of US consumers with bank accounts have used the service. It has achieved profitability multiple times in its history and intends to return to profitability in 2024 after a period of product investing. After a slower 2022, the company seems to be witnessing impressive growth again, logging record sales in recent quarters.

Stacking revenue

Plaid’s evolved product suite has propelled it to these new heights. It now has multiple products to cross-sell to customers, allowing it to stack revenue from numerous sources. Fintechs that have historically relied on Plaid for banking data use it to prevent fraud and streamline transactions.

According to Plaid, this has resulted in an extremely diversified revenue base. At the moment, no single product maintains a majority of revenue. This is impressive work for a business that was effectively a single product for much of its life. It suggests that at least a good portion of the ancillary bets the firm has made have logged real traction and are contributing to the bottom line.

Given that most of Plaid’s customer base likely does not use its full range of APIs, it’s exciting to think of how it may be capable of stacking revenue in the years to come. In time, each customer may leverage half a dozen different products. If Plaid can crack that dynamic, it can unlock strong net revenue retention (NRR), an engine for long-term growth.

Beyond fintechs

As our discussion of Plaid’s credit products showed, the company is no longer simply a vendor for fintechs. It has grown to serve a broad swathe of customers, including more traditional enterprises. Alongside the logos of fintechs like Petal, Esusu, Chime, Betterment, and SoFi, Plaid’s website showcases used car marketplaces like Shift, freight forwarders like Flexport, and credit unions like Veridian.

COO Eric Sager discussed this transition. “We very much started with smaller fintechs,” he said. “While we’ve never moved away from that – if you’re starting a fintech today, you’re still very likely to build on top of Plaid – we have been able to extend ourselves. It’s not just startups using us but larger financial services companies, banking and wealth management customers, and industrial companies. It’s been incredible to see.” That transformation is reflected in the numbers. According to Plaid, since 2022, more than 50% of its new deals have taken place outside the traditional consumer fintech industry. As it demonstrates its value to new customer types, observing how this percentage changes will be interesting.

In addition to expanding beyond fintechs, Plaid has also grown geographically. It offers at least partial services in more than 17 countries, with ex-US coverage concentrated in Europe, now Plaid’s fastest-growing market.

For Sager, expanding into new geographies reflects the universal demand for Plaid’s products. “There’s a global opportunity,” he said. “A lot of the things we’ve built in the US are very applicable for folks in other geographies as well. It doesn’t matter where you live or where you’re trying to build your business. At the end of the day, living a better financial life is applicable whether you’re in Brazil, Nigeria, Germany, Austria, the Philippines, or the US.”

While growing internationally allows Plaid to serve new customers, it also benefits existing ones. Many of Plaid’s largest customers are international entities with cross-border operations. For example, when a US customer wants to expand into France or Germany, it would be ideal to do so without introducing another provider. Not only is that better for Plaid, increasing usage and outflanking competitors, it should be better for the customer. Providing Plaid’s service is strong, customers could expand and unify insights across countries more easily.

Plaid is still in the early innings of its geographical expansion. Its foray into Europe will not go unchecked. After Plaid stepped away from the deal, Visa acquired Swedish rival Tink for $2.2 billion, giving it a strong foothold in the market. Truelayer is another regional alternative.

In addition to facing new competition, each geography brings particular challenges. For example, Europe’s Open Banking regulations create a radically different market structure to the US. Forging bank connections is easier, meaning that second or third movers can more swiftly catch up to those leading the pack from a coverage perspective. While that may play in Plaid’s favor this time, it invites future insurgents.

All in all, Plaid has matured impressively. Over the past few years, it has morphed from a US-only, single-purpose product into a diverse portfolio of revenue-generating business lines with growing global ambitions.

Culture: Secret ingredients

Among its compelling properties, Plaid is a company that grasps the importance of a secret ingredient: time. It understands where and when time is needed and what it will add to its mixture. This quality manifests in unusual patience, focus, and a long-term orientation.

Leadership

Plaid CEO Zach Perret epitomizes these qualities. As Head of Payments John Anderson remarked, “He’s extremely patient. He plays the long-game.”

Anderson’s assessment comes from experience. He first witnessed this characteristic during his recruitment process. Shopify COO Kaz Nejatian introduced the pair in October 2021, informing Anderson that Perret was building “one of the most interesting things in the world.” Though Anderson knew of Plaid, he hadn’t paid close attention to the business; Nejatian’s recommendation got his attention.

Still, he wasn’t looking for a new job. Over a call that autumn, Anderson told Perret in no uncertain terms that he planned to stay at Meta, where he’d spent more than a decade. Though respectful, Perret was undeterred. Over the following months, he continued to court Anderson, making it clear that he wanted him to be a part of Plaid’s next chapter. Perret made it clear he was willing to wait to make that happen, even if it meant Anderson taking a three-month sabbatical before joining.

The combination of conviction and patience proved decisive. Anderson joined in June 2022, certain he was making the right decision. “It really convinced me that this is a company that is going to be generational,” he said of the process.

Anderson’s onboarding was another example of Perret’s willingness to devote time to people and products that can move the needle. Every morning for his first two months at the company, Perret scheduled 45 minutes for him and Anderson to walk and talk. It’s hard to overstate how significant this investment is for the CEO of a fast-growing decacorn business, especially one navigating a dynamic landscape. It made an impression. “It was something I’d never experienced before,” Anderson said. “It was a huge commitment of time that he made, and it really helped me get up to speed fast.”

Anderson’s story is far from unusual. Ask around, and you’ll find many employees with similar tales. “When someone joins the team, they might say to the person next to them, ‘You know, Zach had been talking to me for 6 to 9 months before I joined,” Perret recounted. “And the person next to them will be say, ‘Same.’”

Perret seems to revel in this part of his job and, by necessity, has become extremely adept at it. “When I was 25, we moved the company from New York to California,” he said. “That was definitely the right decision but I truly knew no one in San Francisco. We had to figure out how to recruit people when we had no networks to recruit them from.” Perret and his team developed an extremely strong outbound recruiting muscle starting from scratch. As the company grew, Plaid became skilled at using existing employees to attract further talent from within their networks. “The reality is that we spend a huge amount of time on talent and people. And I learned it’s something I really enjoy doing. That’s true to this day. I like to joke that half of Silicon Valley has an email from me saying, ‘Hi, I’m Zach. Would you like to work at Plaid?’”

Beyond his patience, Plaid’s CEO is described as an uncommonly calm leader. “If people’s emotional spectrum ranges between 1 and 10, I don’t think I’ve seen Zach go outside 4 to 6,” Index’s Mark Goldberg remarked. “He’s unflappable in a way that I think is very helpful as a big company CEO.”

Such composure should not be mistaken for lassitude. As Anderson notes, Perret has a rabid energy when acquiring new information. “He’s a learner. He reads maniacally, he writes a lot. It’s very similar to what I experienced with Zuck,” the former Meta employee remarked. “You can sit and explain a problem and maybe it’s something I’ve spent three months of my career on, and in 45 minutes, Zach will be an expert on it.”

Perret’s greatest strength may be his vision. “That’s what he’s always spiked on,” Goldberg said. “There’s not a single person I’ve met as a fintech investor that has a more forward-looking view of where the world of financial services is going. He’s the one who should be on center stage talking about it. And that’s why Plaid is the company it is.”

Mark Hawkins is a legend of Silicon Valley. Across a more than forty-year career in tech, Hawkins served as CFO at some of the most influential businesses, including Autodesk, Logitech, and Salesforce. He also acted as President during his seven-year stint at Salesforce. His work and board obligations at companies like Workday and Cloudflare have given Hawkins a front-seat look at effective business leadership. His assessment of Perret serves as a neat synopsis of Plaid’s CEO. “When I met Zach, I met integrity, I met authenticity, and I met humbleness,” Hawkins said. “The great leaders I’ve worked with are not full of themselves, they’re always learning from other people.”

Hawkins also found an executive with the ambition to continue innovating. “You have to be on the right part of the risk frontier,” the former Salesforce executive said of a CEO’s role. “You’re not an administrator, you’re a creator of value and innovation – of products that have never existed before. When I sensed Zach was on the right part of the risk frontier, and the value’s aligned…that’s when I felt my time and trust would be applied well working with Zach.”

The talent vortex

Before Mark Goldberg understood Plaid’s technological advantages, he was attracted to the company’s talent pool. One of his first acts as a new investor at Index in 2015 was to alert the partnership to the potential he saw in Perret’s company. That was in large part thanks to the people the CEO had recruited. “What was clear from the early days of Plaid was that they had probably the strongest talent vortex in fintech,” Goldberg said, referring to the company’s ability to attract and retain talent. “The bar was just insanely high to get a job there.” Over the years, Plaid has recruited and retained many of tech’s best and brightest. Jean-Denis Greze, for example, joined as Head of Engineering in 2017, eventually becoming Plaid’s CTO.

According to Golberg, this tendency took a hit after the Visa deal was struck. “The reality is that a lot of people who wanted to work at a hyper-growth fintech company, that want to work at Plaid, Ramp, Brex, Stripe, don’t want to go work at Visa. And so a lot of employees saw the deal and thought, ‘Ok, this is a natural opportunity for me to pick my head up now and think about where I want to go.’ There were some great people that left that would have definitely been here for the next chapter.”

One of Plaid’s challenges after walking away from Visa was to ensure it could draw back the caliber of talent it had lost. Thankfully, it seems to have recovered quickly, reversing the cycle. “Relative to the market now, people look at Plaid as a place where they can go and build really exciting things,” Goldberg said. “When I’m at a fintech event or a happy hour or something, it's clear that Plaid is still the gold standard when it comes to a hiring brand. And that’s a lot of the reason we’re still so bullish on the company’s ability to go multi-product. They have to execute, but they have all the ingredients.”

Look at Plaid’s senior incoming leadership over the past couple of years, and it’s easy to understand where Goldberg is coming from. The following nine (!) executives are an example of the talent Plaid has secured since recommitting to life as an independent company:

Al Cook, Chief Marketing Officer. After eight years at Twilio, Cook joined Plaid in 2022. At the communications API firm, Cook acted as a long-time VP, with a stint leading Twilio’s artificial intelligence efforts. He previously worked at Metaswitch, acquired by Microsoft in 2020.

Meghan Welch, Chief People Officer. Welch joined from former nemesis and current partner, Capital One. Over a 25 year term at the financial behemoth, Welch rose from a recruiting associate to an EVP role.

Sheila Jambekar, Chief Privacy Officer. Jambekar is another ex-Twilio addition, fortifying Plaid’s API braintrust. Over six years, Plaid’s new CPO advanced from a senior counsel role to a VP position. Jambekar also worked for three years at Zynga.

Tom Daniels, Chief Information Security Officer. Daniels spent more than seven years at Square, concluding his time with a stint as CISO. He previously worked at iSEC Partners and PricewaterhouseCoopers.

John Anderson, Head of Payments. As mentioned, Anderson joined Plaid after a decade-long spell at Meta where he worked on payments and Oculus. Anderson’s fintech experience stretches back to the early 2000s; he worked at eBay during its game-changing acquisition of PayPal.

Alain Meier, Head of Identity. After Cognito was acquired in 2022, Meier established himself as Plaid’s Head of Identity. In this role, Meier is tasked with evolving the core technology his startup developed and pushing it in new directions. The expertise he built over nearly nine years at Cognito is invaluable, giving Plaid genuine identity expertise and product vision.

Cecilia Frew, Head of Open Finance. Frew brings SVP experience from both PNC Bank and Plaid’s almost-acquirer, Visa. She also served as SVP and GM at Equifax. She uses this deep industry knowledge to oversee Plaid's commercial and connectivity partnerships with banks.

Mike Saunders, Head of Credit. Saunders left his stint as CEO of Southeast Asian fintech ZaloPay to join Plaid. Before his time at the Vietnamese unicorn, Saunders spent six years on Amazon’s payments team, four years at Barclaycard, and 11 at American Express.

Tamara Romanek, Head of Partnerships. Like Saunders, Romanek brings deep payment experience to Plaid. After a decade at Visa – split between two stints – Romanek worked on Meta’s payments team, forging partnerships across the financial ecosystem. She is charged with doing the same at Plaid, across over 50 payment partners.

As well as demonstrating Perret’s impressive recruiting chops, these additions hint at the organizational approach Plaid may be shifting toward. Multi-product companies often move toward a more federated structure that allows individual business units to operate more independently. Perret seems to have found three CEO-lites capable of managing and growing their divisions in Anderson, Meier, and Saunders. As Plaid looks to cement itself as a comprehensive platform, providing the latitude for individual product groups to evolve could prove pivotal.

Culture

Though every earnest enterprise hopes to become a mission-driven company, not all succeed. Plaid is an example of a firm that feels its mission at a fundamental level. Given its origins as a response to traditional banking’s consumer hostility, perhaps that DNA is to be expected. It is no less impressive. Plaid team members frequently reference the importance of the company’s work and its mission to improve financial access.

“It’s a very mission-driven place,” COO Eric Sager remarked. “From Zach on down, people genuinely believe that by building the infrastructure we’re building, we’re enabling startups, developers, and our customers more broadly to build amazing solutions that improve the lives of countless millions of individuals and small businesses.” He added that the team feels a deep responsibility for the product it is bringing into the world. “I think we have an obligation, and we take it very seriously, to make sure that all of that happens in an incredibly transparent and secure way.”

Plaid’s sense of mission is not abstract but ingrained in its operations. As we’ve discussed, at a fundamental level, end consumers are not Plaid’s customers; the firm explicitly makes no money from them and does not plan to. And yet, consumers are at the heart of how Plaid runs. “When we’re trying to decide what to build and how to build it, the conversation almost always starts with asking, ‘Ok, what’s best for consumers?’” Sager said. “That comes from the mission. I think if we had a different mission, I don’t think I or the team would think about it the same way we do today.”

A resonant, tangible mission has created a culture of true customer obsession. Plaid is an organization that seeks to solve problems by talking to its user base and orients itself around service. Michelle Boros, Product Lead for Credit, experienced this as a customer first. Before joining Plaid, Boros worked at Figure, a lender that relied on Plaid’s services. “Everybody I interacted with was super smart, and they cared about the work they were doing,” she recalled. “They cared about me as a customer.” When the opportunity to hop aboard arose, Boros wondered whether her impression of a customer-focused firm would be reflected in reality.

Thankfully, it was. “The big really distinctive element of Plaid’s culture is how much our product teams are steeped in the actual market,” John Anderson remarked. “We talk every day about the customer conversations we had. It’s kind of cliche to say, ‘We’re maniacal about the customer.’ But what I can say is that the most successful product leads at this company are the ones that are very comfortable sitting down and really talking to our customers.”

Index’s Mark Goldberg noted that this obsessiveness has been a part of Plaid’s DNA for years. “Every board meeting always started with NPS. Which I thought was killer. So many other companies start with financials, it's about, ‘Hey, did you hit or miss revenue targets? Or what’s the gross margin?’ And Plaid is just like, ‘NPS. Because that’s the leading indicator of success.’”

For Goldberg, that was a clear indication of the firm’s priorities. “After the Series C, that was one of the more interesting takeaways – that they really care about making customers happy.”

Retaining this trait at scale is rare. Keeping this connection to customers is critical as Plaid enters new markets and introduces new products.

Few people have studied leadership as closely as Doris Kearns Goodwin. The historian has authored many of the best-respected biographies of America’s political leaders, including Team of Rivals, covering Lincoln’s tenure. This is Goodwin’s definition of leadership: “Good leadership requires you to surround yourself with people of diverse perspectives who can disagree with you without fear of retaliation.”

On this dimension, too, Plaid appears to have excelled. Employees describe a low-ego, non-hierarchical management structure that invites candor. “One thing that’s been very very consistent at Plaid is that there’s a focus on ensuring every person’s voice is heard,” Head of Universal Access Raja Chakravorti remarked. “It’s an incredibly flat organization but one that has a really diverse set of talents. That allows us to build into product areas that you might not think of off the bat.”

Plaid seeks to make navigating disagreements easier through a quirky custom. When employees are set to have a difficult conversation, they are encouraged to do so while holding one of the stuffed animals that adorn the company’s HQ. On any given day, you may find two Plaid employees facing one another in animated discussion, clutching Pikachu and Jigglypuff plush toys. It is a small sign of a company that puts its mission, customer obsession, and candor above individual egos.

Risks: Navigating change

Plaid has the kind of defensibility entrepreneurs dream of building. That doesn’t mean it is free from risks, though. To reach its fullest potential, Plaid must reckon with a bull market valuation and the increased commodification of its core offering. It will also need to navigate a changing payments landscape.

Bull-market valuation

Plaid’s Series D offered immediate validation. Within a few months of walking away from the Visa deal in early 2021, Perret nearly tripled his company’s valuation, at least on paper. While Visa proposed a $5.3 billion acquisition, crossover fund Altimeter Capital priced Plaid at $13.4 billion. It served a clear purpose, providing fresh funding and galvanizing employees.

Now that the market has cooled, it’s reasonable to wonder whether Plaid would attract the same valuation today. Plaid doesn’t share its revenue data, which makes a definitive assessment tricky. External parties have estimated the firm’s annual run rate (ARR) over the years, pegging it at around $170 million in late 2020 and $250 million in 2021. Historically, growth rates have tended to be north of 50%, though one source remarked that market conditions had affected the firm’s trajectory in 2022. This year has apparently seen an uptick, though it’s not clear by how much. Assuming annual growth rates between 10% and 25%, we can create an estimated ARR range of approximately $300 million to $390 million. Using a middle ground of $350 million implies a multiple of approximately 38x.

Because Plaid is a unique business, finding a perfect public comparison isn’t easy. (It also means it arguably commands a premium.) Freda Duan of Altimeter Capital believes the firm can be valued like a traditional software company, with a few fintech players thrown in for good measure. Snowflake, Datadog, Bill.com, Shopify, and Adyen are relevant comparisons in the investor’s eyes. That group sees enterprise value (EV) to estimated revenue (FY1) multiples between 10x (Shopify) and 31x (Adyen). Compared to that set, and assuming our estimates for Plaid are in the right ballpark, the private firm’s valuation would be past the high end of that spectrum. For Plaid to merit that valuation, it would need to be growing at a rate considerably higher than those companies listed.

For now, a potential valuation discrepancy won’t bother Plaid much. It reportedly has plenty of capital in the bank and is pursuing sustainability. “The high-level advice we gave them is that they have to get to free cash flow,” Freda Duan remarked. On this front, Plaid seems to be doing very well. “They’re on the right trajectory. If you ask me, I’m pretty confident they can generate free cash flow and breakeven, given they are not burning a ton this year.”

If it continues to adhere to its strategy, the company should be able to control its destiny and time a public market debut. Though we shouldn’t expect any imminent news, Perret and his team are building that muscle. “They’re honestly pretty plugged into the public markets,” Duan said. “They know pretty well how the market thinks about a company. They know the path they need to take.”

Commoditized core

In some respects, Plaid is a victim of its success. When the company started, connecting fintech apps and technology-illiterate banks was extremely difficult. The absence of legible APIs prompted the company to utilize screen-scraping – a matter of necessity, not choice.

However, Plaid’s growth has helped usher in the fintech revolution. Today, all major banks offer consumer-grade applications and frequently supply easy-to-use APIs. Today about 75% of traffic on Plaid’s network now comes from API connections. While the big banks have technical resources to build and manage these APIs, many thousands of smaller banks do not. For those institutions, Plaid developed Core Exchange, an “API in a box” solution that makes it easy for any institution to “plug in” to Plaid’s network and initiate secure API connectivity on behalf of their customers. Though open banking improves the experience for consumers, leading to fewer glitches and disconnections, it also reduces Plaid’s defensibility. If newcomers entered the market today, they would find it much easier to build connections with top banks. While they might struggle to match Plaid’s long tail of 12,000 institutions, they could fairly easily offer coverage of JPMorgan, Goldman Sachs, Wells Fargo, and a few dozen others.

In some respects, this dynamic is playing out – albeit with a more mature competitive set. Plaid’s three closest competitors are all older: Yodlee, Finicity, and MX Technologies. Yodlee and Finicity were founded in 1999, while MX got off the ground in 2010. Of these, only MX is still independent (valued at $1.9 billion); Envestnet snapped up Yodlee for $660 million, while Mastercard acquired Finicity in a deal worth up to $985 million.

Because connecting with banks is no longer so difficult, this trio offers bank-linking products with similar coverage to Plaid’s. Their presence also allows other rivals to enter the fray. Last year Stripe launched a rival product dubbed “Financial Connections.” Under the hood, it is powered by Finicity and MX, relying on their web of banking connections.

Stripe’s entrance – and the ostensible parity in coverage between Plaid and its rivals – poses a question: is Plaid’s core bank linking products becoming commoditized?

It depends on one’s vantage. Compared to the past, building coverage is undoubtedly easier, reducing Plaid’s differentiation. However, in the present, Perret’s company may still have an edge. To understand Plaid’s place in the market, Altimeter’s Freda Duan has conducted 20-plus customer calls. Those conversations give her conviction that Plaid’s essential product remains the industry standard. “Customers tell me that it’s very sticky. I think Plaid is still very clearly the market leader in the US.” Typically, one would expect to see commoditization lead to pricing compressions; Duan has observed the opposite. “It’s charged at a premium versus some of its competitors. And people still choose Plaid because the product is better.” Though a small sample, it’s an interesting indication of how Plaid is holding up, despite new pressures.