How to Raise Your First Fund

A tactical playbook to kickstart your investing journey and set you up for success.

🌟 Hey there! This is a subscriber-only edition of our premium newsletter designed to make you a better investor, founder, and technologist. Members get access to the strategies, tactics, and wisdom of exceptional investors and founders. Become a member today.

Friends,

For most of its existence, venture capital has been a cottage industry practiced by the few and limited to a small corner of California. Though the last couple of decades have broadened its scope and influence, the asset class’s Power Law means that only a few truly excel, deliver, and matter. If you wanted to, you could probably squeeze them all onto a single 737: Peter Thiel stretched out in the exit row, Reid Hoffman perusing the in-flight magazine, Vinod Khosla peering over the pilot’s dash – a Master of the Universe for every middle seat.

If you’re eager to hone the craft of investing, this presents a problem. The best, highest-signal advice is trapped in a couple of hundred heads. Articles, podcasts, tweets, and blog posts offer insights but often elide the information other practitioners find most helpful. How exactly did an investor win over their first institutional LP? What trade-offs did they make when raising their fund? Which sourcing channels are most effective for them and why? What tools do they use to run their internal systems? How long did it take them to raise capital? When do they sell secondary shares and how large a stake do they sell? What do they do when competing head-to-head for a deal?

Today, we’re launching the Investors Guide series to answer these questions and many more. Over ten editions, we’ll break down the essential challenges of raising, running, and succeeding as a private market investor.

To do that, we’re conducting comprehensive interviews with more than 30 exceptional practitioners. These are investors who are either frequent flyers on IRR Air’s 737 or practitioners who we think are primed to get a ticket of their own in the coming years. This group includes early investors in many of the most consequential and successful companies of the past decades, including Canva, Nubank, Faire, Reddit, Coupang, Credit Karma, Chime, SoFi, Lyft, Recursion, Solana, Impossible Foods, Runway, and others. Many are repeat Midas List awardees; others will be in the years to come.

We’ve purposefully compiled a varied group spanning different sectors, geographies, styles, and stages. You’ll hear from insurgent AI managers, long-time generalist GPs, Latam experts, and NYC-focused players. By doing so, you’ll see how great investors often come up with different approaches to the same problems. Whether you’re an angel just dipping your toe into investing, an emerging manager building out your practice, a tenured VC with your own 737 seat, or a founder wanting to know how the other side of the table thinks – there will be fresh information and new lessons to discover.

To give you a preview, here’s what’s coming up with our first season of Investors Guides:

How to raise your first fund (Today!)

How to get your first institutional investor

How to size your investments

How to be a top 1% angel

How to actually add value

How to build a unique voice in the ecosystem

How to win at secondaries

**Secret bonus edition 🤫**

Having already conducted many of the interviews for this entire season, I could not be more excited to share this with you all. I’ve learned a ton so far and can’t wait to go even deeper. To ensure you get all of our insights first and in full, join as a premium member today. If you’ve been looking for a nudge to join – this is it.

Brought to you by Mercury

To stand out to a VC raising their first fund, you need more than a focus on growth and innovation — you need to be more financially disciplined than ever before. That’s why Mercury designed software to simplify your financial operations so you can perform at your best.

Mercury’s VP of Finance, Dan Kang, shares seven fundamentals to prioritize to set your company up for success, from day-to-day operations like payroll to measuring your company’s financial health.

How to raise your first fund

To kick the series off, we’re focusing on an essential topic: How to raise your first fund.

What should you understand about the venture game before you get started? What questions should you ask a potential partner before committing to working together? How do you build a track record before you get your first LPs? What do you need to do to differentiate yourself from the pack? What size vehicle should you raise? Should you get an anchor LP? What does it look like to run a tight fundraising process?

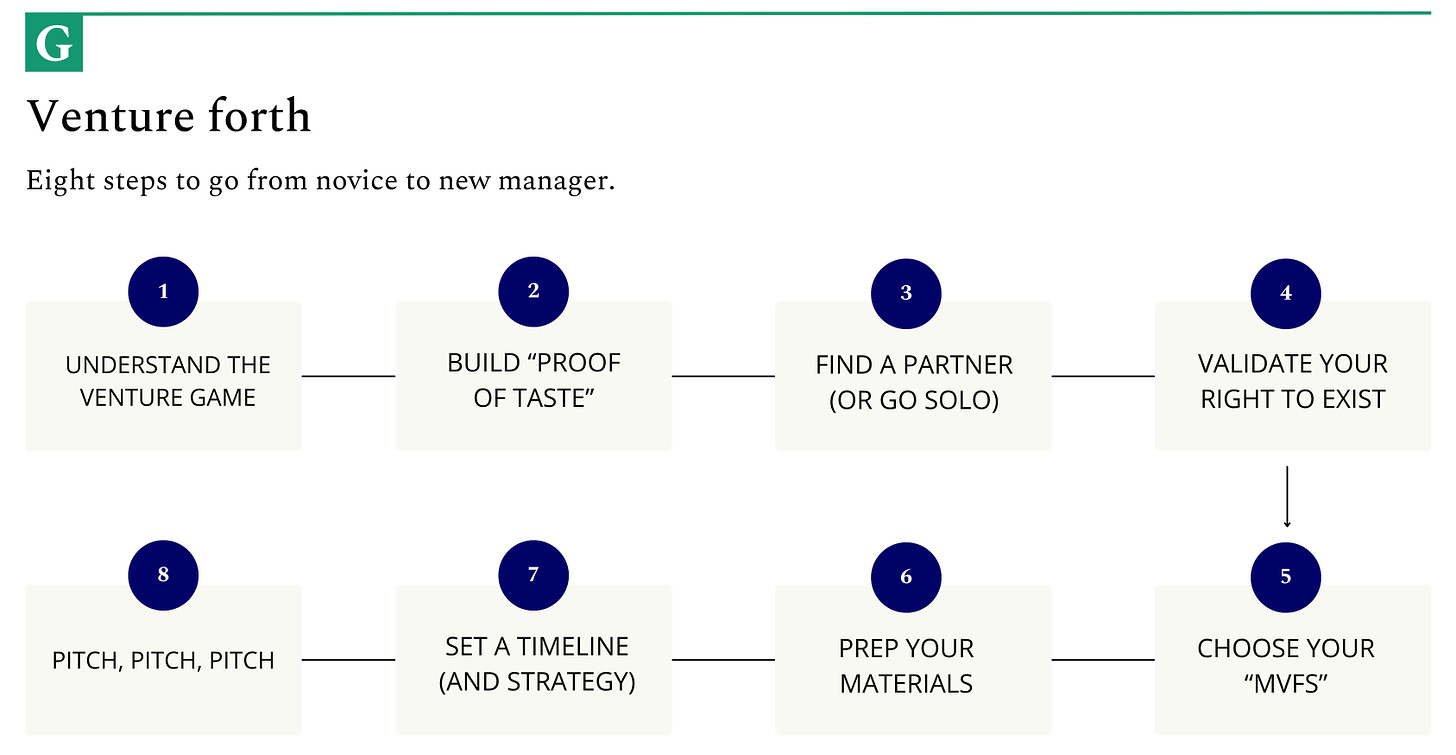

To guide you, we’ve compiled hours worth of tactical wisdom into eight steps:

1. Understand the venture game

Separate parody from reality

Learn to love reading

Grasp the quirks of the asset class

Play the long game

2. Build “proof of taste”

Bankrolling your own fund

Angel investing

Scout programs

The value of writing

Fantasy portfolios

3. Find a partner (or go solo)

Run a vetting process

Practice working together

Optimize for affection and respect

4. Validate your right to exist

Find an edge

Recognize venture is zero-sum

Explore different sources of differentiation

Specialize in a sector, geography, or thesis

Leverage unique assets and advantages

5. Choose your “MVFS” (Minimum Viable Fund Size)

Determine the capital needed to run your strategy

Figure out at what size your approach breaks

Consider putting your skin in the game

6. Prep your materials

Build a deck that emphasizes your advantages

Have your track record at the ready

Construct a fund model

Offer references

If you can, warehouse a successful deal

7. Set a timeline

Decide which LPs you want to pitch

Methods of contacting them

Figure out the right timing and sequencing

8. Pitch, pitch, pitch

Connect as a person

Demonstrate progress

Find “lighthouse” LPs

Expand your prospects

Learn to cut your losses

Focus on the long-term

Thank you to Ben Sun (Primary), Frank Rotman (QED), Hernan Kazah (Kaszek), Kirsten Green (Forerunner), Kyle Samani (Multicoin), Molly Mielke (Moth), Nathan Benaich (Air Street), Nikhil Basu-Trivedi (Footwork), Ann Miura-Ko (Floodgate) Niki Scevak (Blackbird), and Zoe Weinberg (Ex/ante) for sharing their insights for this issue of the Investors Guide series.

Step 1: Understand the venture game

Before you begin, it’s worth asking yourself: do you really want to be a VC? Parodies present tech investing as an easy gig that requires nothing more than choosing from a closet full of fleece vests, coasting up Sand Hill Road in your Model S, and posting up at Philz to pontificate on Twitter.

Those may be good ways to play at being a VC, but they are not the reality. If you care about actually returning multiples of capital to LPs and helping startups, you will need to make friends with risk, develop patience, and learn to filter out noise.

Air Street

The first and most important point to understand is that venture is hard. Scrolling down your X feed, it may look easy to find founders, write checks, and tweet about it, but this conceals 99% of the real work.

– Nathan Benaich

QED

The job of a venture capitalist is very easy to do poorly and difficult to do well. Everyone needs to internalize that concept before they even start. Handing out checks is easy. But to do it into the right companies? That’s hard.

So many people enter the VC world because they think it’s just a cool profession and they want to talk to charismatic founders.

– Frank Rotman

One way to test whether you actually want to be an investor is to ignore the results of being a successful VC (wealth, esteem) and focus on the process. What do the investors you admire do every day? How many meetings are they taking? How do they spend their time? What percent of their time do they spend reading research papers or meeting with scientific minds? If you aspire to run a firm of your own, how much time should you expect to devote to personnel and operations? How many hours are devoted to cultivating LP relationships and fundraising?

We’ll unpack these facets in this guide and several others. One sign that you might enjoy the inputs of being an investor is that you have a voracious appetite for information. Warren Buffett famously spends 80% of his working hours reading (or thinking). Other VCs gravitated to the profession because they had a similar proclivity for information consumption.

Multicoin

I like reading all day. I can read all day, every day. If you’re the kind of person who wants to read all day every day, that’s probably a good signal you want to invest, not build.

– Kyle Samani

Compared to other asset classes, venture capital has several fairly unique quirks worth considering.

Extremely long feedback loops. It takes over a decade for a successful startup to develop into a thriving public company. As an investor, you won’t receive positive feedback for +10 years. You will receive plenty of negative feedback in that time, as many of your companies shut down. Maintaining belief in your abilities and processes absent confirming information takes a degree of productive delusion and strong self-confidence.

Rapidly changing playing field. Venture investors back companies at the technological frontier. By definition, these businesses are highly disruptive, often radically changing the broader landscape. Startups that look bulletproof one moment can be vulnerable the next. The same is true of your edge – you might have an advantage underwriting a certain type of business, only for that category to crumple under new pressures.

Strong brand persistence. The venture capital firms with the best “brands” tend to keep winning. Because they’re held in high regard, these franchises tend to see the most attractive deals first and have greater leverage to negotiate preferable terms. This disadvantages insurgents. If you’re a new fund going head-to-head with Sequoia or Founders Fund, it’s likely you will lose – or pay much, much more.

Extremely noisy and mimetic. The competition in venture capital has incentivized practitioners to brand themselves and promote their services. The result is a noisy ecosystem in constant conversation. Additionally, because of the long feedback loops mentioned earlier, it is tempting to follow the lead of more experienced, higher-status investors, resulting in many mimetic behaviors.

Ability to influence the outcome. Though VCs can damage the companies they invest in by providing bad advice, they can also genuinely add value. The right introduction or hire can provide a step change improvement to a startup. While VCs have to be careful not to detract from their portfolio, the fact that you can influence the outcome of an investment is worth understanding at a deep level.

Huge error rates. The world’s best VCs are wrong the vast majority of the time. To succeed in the asset class, you must get comfortable with this level of “failure.” Most of the companies you back will die. That does not necessarily mean you are a terrible investor (though it also might!); it means you are simply on track.

Extremely skewed outcomes. Venture’s distribution of returns is extremely skewed. Even an above-average investor may lose money. To be truly great, you can’t simply be in the top 25% but the top 10% or 1%. You could spend decades of your life in pursuit of excellence and end your career knowing you were little better than average.

Luck and skill are easily conflated. As Ho Nam outlined in the last edition of “Letters to a Young Investor,” a VC’s career is often defined by just one company – two, if you’re lucky. As a result, it’s very difficult to tell who got lucky and who is genuinely skilled. If you’re someone who likes to study greatness as a way to learn, this presents a challenge. You will need to dig into the practices of the ecosystem’s best returners to try and differentiate repeatable success from simple luck.

Ultimately, if you want to work in this asset class, you should make sure you’re in it for the long term and are focused on the right incentives. Otherwise, it’s easy to get distracted by shiny objects and meaningless, transient victories.

QED

If your goal is to get quick mark-ups so you can raise your next fund, you’re fucked.

– Frank Rotman

Step 2: Build “proof of good taste”

Congratulations!

You have decided you would like to forge a career in venture. Now, the real work begins.

To get someone to give you money to invest, you need to prove you can make good use of it. This isn’t strictly true. If you are a very famous or influential person, it’s possible people will give you money simply because of who you are. But for those of us who haven’t won a Grammy or gold medal, it’s a good rule of thumb. It is also essential to prove to yourself that you enjoy the job and have at least a chance of being good at it.

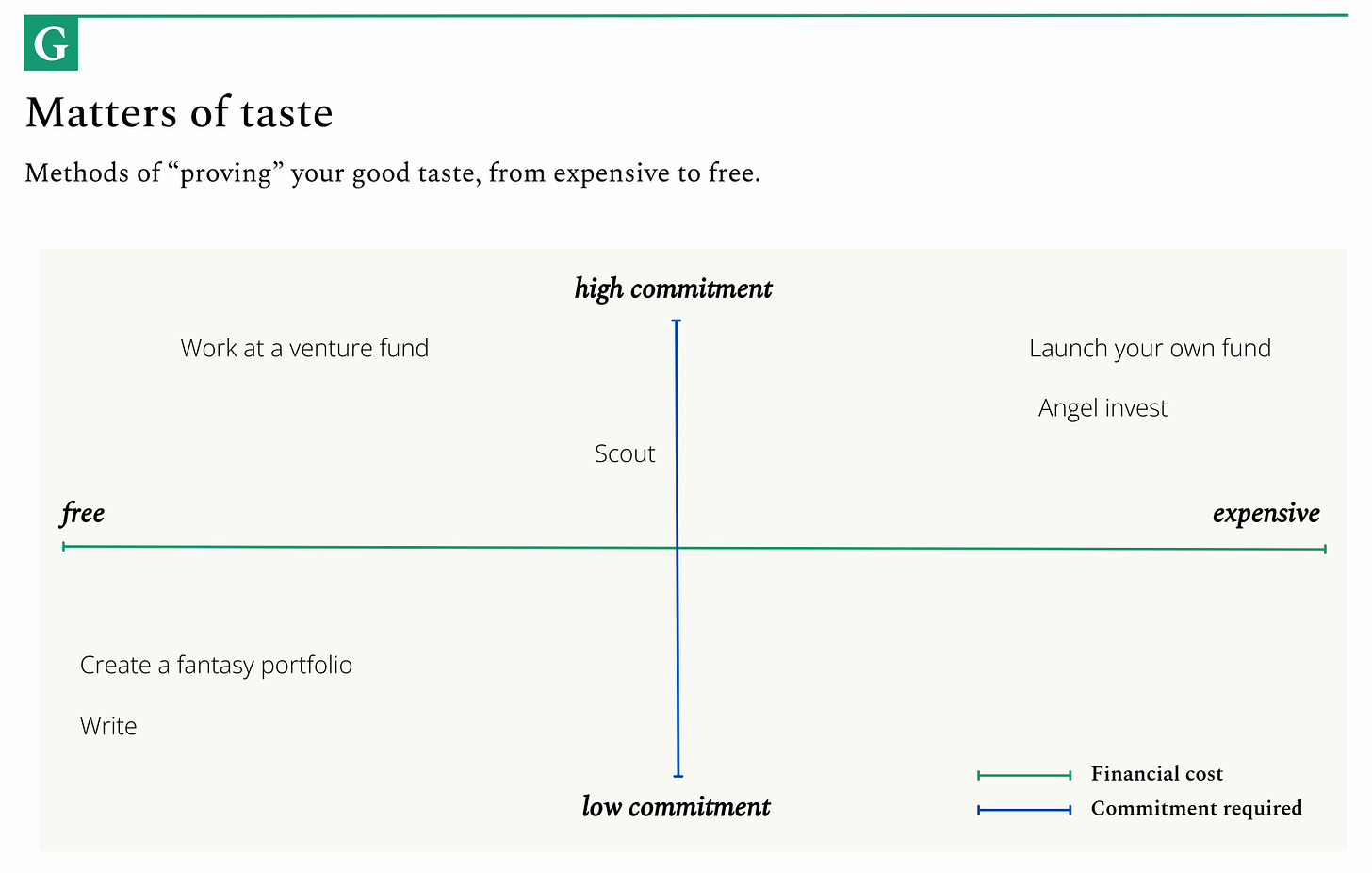

To do so, you need to build “proof of good taste.” There are many ways to do this, ranging from extremely expensive to entirely free.

The most capital-intensive approach is to launch a fund backed by your own money. This can make sense if you’re a successful founder or executive keen to test out VC without risking anyone else’s capital.

QED

For us, starting QED was a big, grand experiment. We had no idea if we’d be good as investors and we had no idea if the market would want our product. So we said, “Well, the easiest way is to try with our own money. If we don’t like it or no one wants it, we can wind it down.”

We kind of pinky-swore to each other that we would be honest about whether it was something we wanted to do for the long-term or if it was working or not working. For the first two or three years, we didn’t even have a website. We didn’t go public with who we were – it was all behind the scenes.

When the opportunity in fintech got larger than our capital base, that’s when we decided to raise our first outside funds. It was a big decision, but by then we had a track record. It’s much easier to raise outside capital when you have a track record.

– Frank Rotman

A lighter-weight option is simply angel investing. This does require capital of your own but is viewed a little differently. If you launch a fund backed entirely by your own money and one day decide to raise from outside LPs, they will likely view that effort quite seriously. Angel investing is a bit more casual and exploratory. While developing a strong angel track record that nicely dovetails with your future fund’s strategy is helpful, it’s ok if it’s a bit messier. You can invest across sectors and stages, discovering what you’re most excited by and where you think you have the sharpest edge.

Though angel investing is undoubtedly costly, it might not be quite as expensive as you think. If you can demonstrate value to entrepreneurs, many are willing to accept extremely small checks—$1K to $5K. With a bankroll of $20K, you can begin to build a real mini-portfolio.

To be clear, you should prepare to lose everything you invest. But depending on your financial status, this may be a worthwhile educational cost. You’ll learn how to approach founders, network with other investors, evaluate deals, and experience the depressing chill of making a bad investment.

Working as a venture scout is an alternative that doesn’t require capital of your own. If you’re connected to entrepreneurs, large venture firms may invite you to deploy capital on their behalf. Sequoia, a16z, Index, and Accel are all known to run scout programs.

Though you won’t risk your own money, you may not have quite as much freedom. You’re typically investing in early-stage companies (putting them on your benefactor’s radar) and may have other geographic or sector limitations.

If you don’t have either your own or someone else’s capital to invest, don’t worry. There are entirely free ways to prove your investing taste.

Writing is a great, free way of demonstrating differentiated thinking, research chops, or mastery of a subject. This works especially well if you write about a subject that is “hot” but poorly understood.

Multicoin

We leaned on our blog to prove our taste, which worked incredibly well. Especially in crypto there were all these guys who were 40 years old, married with kids, and they really wanted to degen with crypto. They had no more than 30 minutes a day to read and they would discover our blog somehow and think, “Fuck, these guys know what’s up.” A lot of our early LPs were people like that.

– Kyle Samani

If you want something a little more applied, you could pull together a “fantasy” or “shadow” portfolio. Imagine you’ve raised a $10 million fund – where would you invest it? Which startups covered by TechCrunch or posted on Hacker News would you back if given the chance? How much would you deploy and why? What would your investment memo for the company look like? Turner Novak, GP of Banana Capital, shared his fantasy portfolio in 2018 before he raised his own fund. For several years before and during my time in VC, I did something similar, logging investments in a database I titled “Invisible Ventures.”

It’s an excellent way to test your thinking, time-stamp your predictions, and softly prove your taste. The downside of this approach is that you don’t prove your access – your fantasy portfolio could be comprised of startups you would never have gotten into. Additionally, on the off chance you make good calls, you won’t benefit from them financially.

If you’re set on raising a fund in the near future, an additional free way to demonstrate taste is to start proactively sourcing companies. When you pitch LPs, you’ll have a set of companies you hope to invest in that demonstrate your approach. This requires trust – entrepreneurs aren’t likely to let you conditionally invest unless they know and value you.

Moth

I had a couple of startups I knew were about to raise. One was founded by two ex-Stripes, so it was a good, interesting fintech deal that objectively made sense as something to invest in. Then there were a couple of others where I could say, “I’ve been working with these founders for the past year, helping them think through if it’s the right time to fundraise. I’m going to be the first check in – I’ve already promised that, and they’ve accepted.”

Having those deals was helpful because otherwise, LPs would have had no idea what I liked.

– Molly Mielke

Step 3: Find a partner (or go solo)

When starting a fund, few decisions are more important than who you choose to partner with. A great partner improves your thinking, widens your network, and increases the support you can provide to your companies. Meanwhile, a poor partnership can scupper a firm before it even has a chance.

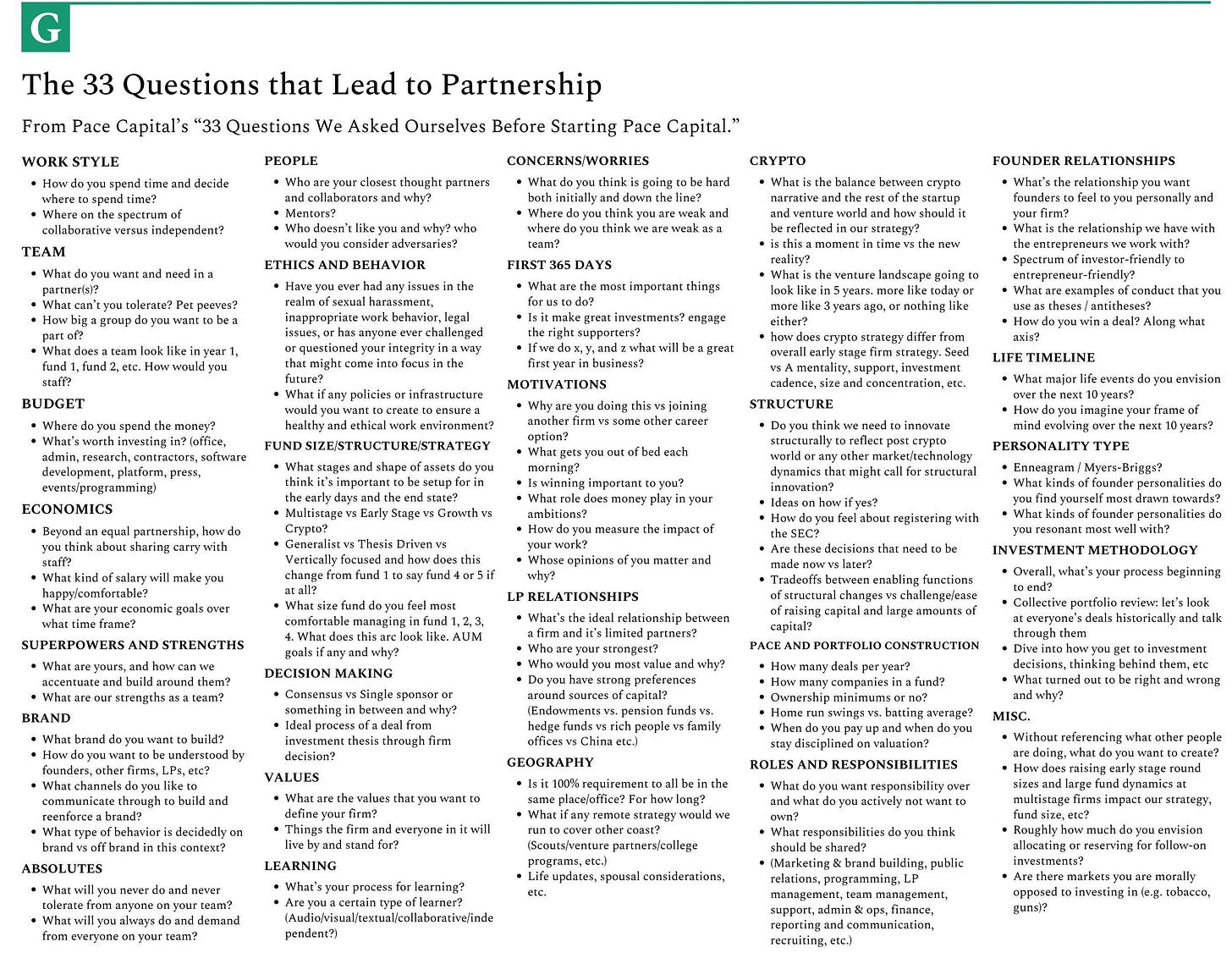

Even if you think you have the perfect person for the job, take the vetting process seriously. Spend time together, ask probing questions, and align on values.

Footwork

The most important thing we did was make sure we were actually aligned on values and principles as a partnership. As part of that process, we modified the 33 questions that Chris Paik and Jordan Cooper used in starting Pace Capital. We subtracted some, we added some – ours became 37 questions.

We answered the questions individually, blind. Then we pasted them together in a doc and stared at our answers together. By doing that, we realized there were a few things we needed to spend more time figuring out. Things like: How do we make decisions together as a team? What is that going to look like? What do we want the firm’s brand to stand for? What does portfolio construction look like? How rigid are we going to be on that?

On some other questions, we quickly knew we were in the right place. For example, we knew we wanted a full equal partnership. We knew we weren’t going to do attribution – we weren’t going to think about Mike’s investments versus my investments. We had the same philosophy around generational transition. If one of us raises our hand and says, “Hey, I’m good. I don’t want to do this anymore” – we want to incentivize that.

We were aligned on a lot of things, but there were a bunch of core elements we had to discuss and flesh out.

– Nikhil Basu Trivedi

While structured introspection is invaluable, nothing beats doing the job together. Find ways to simulate partnership and engage in the craft of investing together.