Watershed: A Climate Pragmatist

The $1 billion carbon accounting platform has attracted investment from Sequoia and Kleiner Perkins. Its greatest strength is its practical, market-driven approach to the climate crisis.

Brought to you by WorkOS

Here’s a puzzle: what do products like Dropbox, Slack, Zoom, and Asana all have in common? The answer is they all were successful because they became enterprise-ready.

Becoming enterprise-ready means adding security and compliance features required by enterprise IT admins. But enterprise features are super complex to build, with lots of weird edge cases, and they typically require months or years of your development time.

WorkOS is a developer platform to make your app enterprise-ready. With a few simple APIs, you can immediately add common enterprise features like Single Sign-On, Multi-Factor Authentication, SCIM user provisioning, and more. Developers will find beautiful docs and SDKs that make integration a breeze, kind of like “Stripe for enterprise features.” Today WorkOS powers apps like Webflow, Hopin, Vercel, and more than 200 others.

Integrate WorkOS now and make your app enterprise-ready.

Actionable insights

If you only have a few minutes to spare, here’s what investors, operators, and founders should know about Watershed.

A climate OS. Companies use Watershed’s platform to measure their carbon footprint, report it to shareholders and governmental agencies, implement reductions over time, and invest in cutting-edge carbon removal programs. It’s a thoughtfully crafted and comprehensive solution that has won over players like Walmart, Stripe, Shopify, and BlackRock.

Planetary markets. For a time, investors looked at the green energy revolution with some skepticism. No longer. There is increasing consensus that the next decades will see a radical reorganization of capital that boosts providers like Watershed. The carbon accounting market alone is projected to hit $64 billion by 2030.

Good influence. Few companies can boast as impressive an investor base or advisory committee as Watershed. The firm counts venture notables John Doerr and Michael Moritz as backers, alongside vice president Al Gore and Laurene Powell Jobs. A slew of former and current public sector powerbrokers bolster its influence. In an increasingly competitive sector, such ties – and implicit trust – could prove pivotal.

Extracting emissions. Some of Watershed’s most exciting work comes not in counting emissions but financing removal methods. In conjunction with Frontier, the platform empowers customers to invest in projects like Charm Industrial and Heirloom that use pioneering techniques to suck CO2 out of the atmosphere.

A rush of rivals. Watershed is not the only firm to recognize the carbon accounting opportunity. Insurgents like Persefoni, Sinai, CarbonChain, and Sweep have all emerged as solutions. The greater threat may come from above: enterprise software megalodons like Microsoft, IBM, and Salesforce have unveiled their own offerings. Watershed will need to keep innovating, and expand beyond its current niche, to fulfill its potential.

In the fall of 2019, Christian Anderson, Taylor Francis, and Avi Itskovich stood in front of a whiteboard, staring at the scrawl: 500 megatons.

This was it. This was why the three friends had gathered in Anderson’s spare bedroom, the reason they had left their jobs at Stripe to strike out on their own: to find a solution to this problem, the dilemma of 500 million tons of carbon dioxide. What could they build to reduce C02 by that figure every year?

Understanding the ambitiousness of the goal requires some context. The year Anderson, Francis, and Itskovich paced, debated, and scribbled in front of their whiteboard, carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions crested 37 billion tons. That same year, Brazil’s total CO2 output surpassed 475 million tons. The former colleagues sought to build something with a climate impact felt on a global scale: slashing total emissions by more than 1%, taking a Brazil-and-a-bit out of the atmosphere.

They gave themselves a deadline. Ten days to come up with a product or company that could make that difference. By the end of the sprint, the trio would start building their best idea.

Four years later, the fruits of that process are evident. Today, Anderson & Company run Watershed, a carbon accounting platform that counts BlackRock, Stripe, Airbnb, Doordash, and Walmart as customers, boasts a $1 billion valuation, and is seen by some as a generational company in the making. The presence of John Doerr and Michael Moritz on the cap table is the clearest indication Watershed is among tech’s anointed few. The last time the legendary Kleiner Perkins and Sequoia rainmakers co-lead a deal was in 1999; the company was Google.

Beyond the impressive names it has attracted, Watershed’s most eye-catching trait is its pragmatism. Though its founders may have started with wide-eyed idealism – 500 megatons – their business is marked by realism, grounded in business logic. In conversation, co-founder Taylor Francis toggles between Watershed’s climate impact and corporate value with almost metronomic regularity: Yes, this is good for the world, but we haven’t forgotten your bottom line.

In this regard, Watershed bears little resemblance to the asset-heavy green economy darlings of the 2000s and much more to enterprise giants like Salesforce or SAP. If that sounds uninspired, it shouldn’t; both boast centacorn valuations and have become core parts of modern business – smoothers of processes, platforms for others to build upon. The climate revolution needs this corporate infrastructure more than most.

Reaching that scale will not come easily. Over the past few years, other entrepreneurs have recognized the carbon accounting opportunity, rushing to fill it. While good news for the planet’s health, it means Watershed’s ascendance will be contested.

Origins: Unforgiving math

When Mauna Loa erupts, the Pacific sky rages orange and pink. Stretched across the Island of Hawaii, the world’s largest active volcano may be 700,000 years old. Over its lifespan, it has been a creature of formidable destruction and awed fascination. In the 1900s, Mauna Loa incinerated local villages; its recent outbursts, including one in 2022, have been much less damaging.

In March of 1958, a young geochemist sat at an observation base on Mauna Loa’s north flank and listened to the earth breathe. Charles David Keeling, just twenty-nine at the time, had garnered support to continue his research into atmospheric carbon dioxide levels. It was a topic few were interested in at the time. Just to make his first measurements, Keeling had constructed a makeshift gas analyzer based on a 1916 journal article; no off-the-shelf options existed.

The first Mauna Loa measurement came in at 313 parts per million, meaning that for every 1 million gas molecules in the atmosphere, 313 were carbon dioxide. That finding alone wasn’t particularly profound – over the decades, other scientists had taken point-in-time samples that noted atmospheric levels. One of Keeling’s advisors had suggested that approach, proposing Keeling return to Mauna Loa after a decade to see how CO2 levels had changed.

The Scranton native had a different vision. Rather than taking measurements every year or decade, what if he tracked carbon dioxide levels daily? What might a detailed chronicle show? What could it tell us about our planet?

Those questions were answered in the following years. Keeling’s measurements followed a predictable pattern and charted a clear trajectory. On a seasonal basis, CO2 levels rose and fell in conjunction with the flowering and retreat of vegetation. As plants blossomed, they sucked carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere, “breathing in” over verdant months. More alarmingly, though levels varied over the course of a year, Keeling’s data showed an inexorable upward trend. Carbon dioxide levels were inarguably increasing.

It was a discovery that fundamentally changed the conversation around global warming. The “Keeling Curve” drew attention to the irrefutable evidence, strengthening the link between human behavior and global warming. It is considered by some to be one of the 20th century’s greatest scientific achievements.

Keeling’s work is also a testament to the importance of accurate measurement. Lord Kelvin – the mathematician who determined true zero temperature for the first time – remarked, “If you cannot measure it, you cannot improve it.”

More than six decades after Keeling started his work in Hawaii, three technologists began their fascination with carbon measurement. Their world was very different than Keeling’s had been, let alone Kelvin’s. By 2019, the Mauna Loa observatory registered CO2 levels of 414.8 ppm – 33% greater than Keeling’s first measurement.

Christian Anderson, Taylor Francis, and Avi Itskovich may not have known that precise figure when they set out to build a climate company, but they had no doubts about the direction of travel. All had grown up on a planet tilting toward disaster and had developed an early appreciation for the crisis humanity faced. Anderson’s father worked as an environmental lawyer, Itskovich was a keen outdoorsman, and Francis had been particularly moved by Al Gore’s documentary, An Inconvenient Truth, which he’d seen as a middle schooler.

It was another interest – technology – that introduced the trio. In 2013, Christian Anderson joined fintech Stripe as an engineer. The next year, Itskovich and Francis followed. Over the next five years, the operators would get to know each other, learning their relative strengths and weaknesses. Backpacking trips strengthened their bond and revealed the importance they placed on time outside and the preservation of the planet. Discussions shared at campsites followed them to San Francisco – and stoked a desire to do more.

The timing of that growing interest was no coincidence. All were familiar with what Francis termed the “unforgiving math” of the climate crisis. In particular, Francis referred to reaching net-zero emissions by 2050, a benchmark that should limit global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius and avoid some of climate change’s most devastating impact. As part of this goal, organizations like the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) have urged the world to halve emissions by 2030. That target made the 2020s feel especially important. “We felt like this was the decade to work on climate,” Francis said.

It took some time for the friends to set out on their own, especially because they hadn’t yet found a business idea. Francis was the first to leave Stripe, departing in the spring of 2019 and spending much of his summer interviewing climate experts to learn about the sector. Itskovich and Anderson left later in the year.

Those final few months of employment proved pivotal in Anderson’s case. A couple of years earlier, Patrick and John Collison started pushing Stripe toward carbon neutrality. In 2019, Anderson was given a chance to further the company’s climate commitment, outlining the new approach in an August blog post, “Decrement carbon.” In it, Anderson stated Stripe’s promise to pay for the direct removal and long-term sequestration of carbon dioxide “at any available price.” Stripe didn’t just want to be carbon neutral; it wanted to be net-negative. To meet that goal, the company committed to spending twice as much on sequestration as offsets, with a minimum of $1 million per year. In the words of one former Department of Energy official, it was a “breathtaking and audacious” initiative. Stripe’s exceptional work in the space over the past few years demonstrates it was just the beginning.

Spearheading Stripe’s negative-emissions policy proved influential for Anderson. The engineer saw the immaturity of the climate accountability space firsthand. Stripe endured significant pain to understand and alleviate its footprint. What chance did less committed or technologically savvy companies have?

At the same that time Anderson observed the scarcity of available tools, he saw the obvious demand for them. Since Stripe had established itself as an early-mover on climate, other companies reached out to the team to understand the process they’d gone through. It became increasingly clear that other enterprises wanted to follow Stripe’s lead; they just didn’t know how.

In autumn 2019, Anderson officially left Stripe. Within days, he stood before a whiteboard, looking at a number: 500 megatons.

Over their ten-day sprint, Anderson, Itskovich, and Francis looked for an idea that could move the needle by that figure. They’d spend their days researching different approaches and then convene in front of the whiteboard to map out each one’s potential impact. “We thought about advocacy ideas, consumer ideas,” Francis said. “And the one where the math made the most sense was B2B.”

The logic was simple, according to Francis: “Most of the carbon in the atmosphere comes from a company that made a choice. And those companies are blind to these choices – you can’t manage what you can’t measure. [We decided] to convert all of the pressure companies were going to feel from regulators and investors and customers…and build software that helps them measure, reduce, and report their emissions.”

The plan was set. Build a software platform and marketplace that the world’s most influential companies would use to understand and reduce their footprint. Watershed was officially born.

Inflection: Economic Imperative

“Over the 40 years of my career in finance, I have witnessed a number of financial crises and challenges,” BlackRock Chairman Larry Fink wrote in a 2020 letter directed to CEOs. “Even when these episodes lasted for many years, they were all, in the broad scheme of things, short-term in nature. Climate change is different. Even if only a fraction of the projected impacts is realized, this is a much more structural, long-term crisis. Companies, investors, and governments must prepare for a significant reallocation of capital.”

Though Fink’s rhetoric sounded prosaic, delivered in bloodless corporate patois, there was no mistaking the significance of his message. The leader of the largest asset manager in the world had just emphasized the importance of climate change – not simply from a humanitarian perspective but as a matter of good governance. “Companies have a responsibility – and an economic imperative – to give shareholders a clear picture of their preparedness,” Fink added. BlackRock’s czar had made the case for carbon accounting.

The impact was keenly felt at Watershed. “It was just an earthquake in the space,” Francis said. By then, the company had started sounding out potential customers and building a basic product. “We talked to a lot of mission-driven founders who were motivated about having their company reflect their values,” Francis said. Fink’s declaration permanently changed the conversation. “Since then, our conversations have been with very hard-nosed CFOs motivated by climate opportunity, climate risk, and climate disclosure as a business imperative.” While Watershed’s founders had always been bullish about the potential for their solution, by early 2020, it was increasingly clear that they were addressing an acute and growing need.

With few available options and the imprimatur of Stripe, the team succeeded in snapping up big-name customers. The first that launched a “very serious deployment” of Watershed, per Francis, was salad chain Sweetgreen. It has turned out to be a productive pairing. In 2021, the fast-casual brand announced its intention to reach net-zero emissions by 2027 and has successfully reduced its emissions “intensity” (a relative basis) by 12% since working with Watershed.

Other early adopters included Block, Shopify, and Airbnb, emphasizing the startup’s ability to serve large customers with even an underdeveloped product. Watershed built a roster of notable names in the following years, including Walmart, Spotify, DoorDash, Bain Capital, Okta, Figma, Canva, Flexport, Pinterest, Wise, Klarna, former employer Stripe, and Larry Fink’s shop, BlackRock. Today, the company reports customers in the hundreds.

The French chemist Louis Pasteur once declared that “chance favors the prepared mind.” As Watershed’s early customer demand attracted investor attention, few in Silicon Valley were as prepared to meet the opportunity as John Doerr.

Beginning in the mid-2000s, the storied Kleiner Perkins investor had developed a keen interest in the green economy. As chronicled in our case study of his venture firm, Doerr’s $1 billion cleantech investments returned $3 billion, underperforming Kleiner’s historical numbers – though they were far from the debacle they are often depicted as. Irrespective of returns, Doerr’s conviction cultivated a deep understanding of the sector and what was needed to propel it forward.

“I had been looking for a business in this space prior to Watershed’s founding,” Doerr shared in our exchange. “For companies to successfully decarbonize, they need to first measure the source of their emissions.” In his 2021 book Speed & Scale, Doerr set a “key result” for the Fortune Global 500 to commit to reaching net zero by 2050. As the Kleiner Chairman explained, “For industries of that size to reach their goals, they will need tools like Watershed, which is specifically designed to help companies measure and manage their emissions on the path to net-zero.”

Doerr needed little convincing on the market or product. He would also build strong convictions in Watershed’s team. Beyond Anderson, Francis, and Itskovich’s sense of mission, Doerr was impressed by their operational bonafides: “They also have a remarkable pedigree, with DNA from one of the world’s best technology companies, Stripe. This experience equips them to approach solutions with the rigor, product discipline, and user-centric design that are hallmarks of Stripe’s success. The founders excel at working with data, building APIs, generating insightful reports, and maintaining simplicity in their products.”

Doerr was not the only one interested in backing Watershed. Sequoia Capital’s Michael Moritz also approached the startup. While the venture icon and erstwhile journalist had not planted his flag in the climate space like his Kleiner counterpart, he’d proved an invaluable partner to Stripe. In Watershed, Moritz saw the makings of a B2B giant: “Just like the early days of other enterprise software categories – databases, ERP, sales-force management – corporate climate management has been the preserve of consultants and custom programming. Watershed is turning climate management into the next category of enterprise software.”

In the end, Kleiner and Sequoia co-led Watershed’s first round of funding, a $14.5 million Series A announced in early 2021. A year later, the climate platform reported it had secured a $70 million Series B at a $1 billion valuation, led by the same partners. As much as Watershed’s fast fundraising trajectory and choice of firms speaks to the esteem in which it is held, its partner pairing is most eye-catching. “It’s wonderful to partner with Mike Moritz from Sequoia again,” Doerr said. “We worked together on Google for their Series A. Now we’re in Watershed together.”

In less than four years, Watershed has evolved from a half-thought muttered in front of a whiteboard to a climate unicorn, backed by two of Silicon Valley’s all-time greatest investors and serving some of the world’s largest companies.

Opportunity: Averting apocalypse

Few politicians have had as compelling an after-office career as Al Gore. America’s 45th vice president has dedicated his second act to combating climate change. While he is best known for the documentary that inspired Taylor Francis, An Inconvenient Truth, and the Nobel Peace Prize that helped earn, Gore has also been an active investor in green solutions. In 2004, he founded Generation Investment Management alongside David Blood, the former Goldman Sachs Asset Management CEO. With that lens, the ex-statesman declared climate change “the single largest investment in history.”

It is a brazen, compelling pitch. What greater impetus to mobilize assets is there than saving the planet? What more urgent priority can there be?

With this in mind, we can assess the scale of Watershed’s opportunity. How big can Anderson’s company become? Could a climate enterprise solution hit Salesforce’s nearly $200 billion market cap? Might it even surpass those heights?

For now, those comparisons are premature. The last round of funding Watershed announced pegged the company at $1 billion – a different ballpark than Marc Benioff’s monolith.

From a high level, at least, it’s easy to feel bullish about Watershed’s potential. The platform is positioned to be one of the primary beneficiaries of the quest to avert the apocalypse. It will not capture all of the value created in this process, of course – many other innovations will be needed, from zero-carbon cement to synthetic meat to nuclear fusion. But as the system of record for enterprises and the marketplace through which they purchase carbon removals and clean energy, it is well positioned to capitalize on a growing need.

The carbon accounting market was pegged at $12.73 billion in 2022. As you might expect, it’s projected to grow rapidly, exceeding $64 billion by 2030. It’s unlikely to flatline from there. Companies face increasing market and regulatory pressure to measure, report, and reduce emissions. In 2021, for example, a group of asset managers representing $130 trillion committed to driving emissions toward net zero by 2050. In March 2022, the SEC proposed new climate disclosure rules; although they have not been implemented, many companies have started proactively complying. As big businesses finally embrace the green gospel, products like Watershed will be among their first purchases.

These figures only cover part of Watershed’s current opportunity set. As mentioned, the startup facilitates climate-positive purchases. There’s plenty of nuance in the types of transactions Watershed permits, but there’s little doubt that spending in this area could be extremely significant. The carbon offset market may hit $190 billion as soon as 2030, according to Bloomberg, though given total purchases were just $1 billion in 2021, that may be overly optimistic. Mark Carney, a special envoy to the United Nations on climate finance, suggested the carbon credits market might be worth $150 billion annually.

At that size, even a virtual broker like Watershed, which likely clips just a few percent in fees, could still build a large revenue stream. That should only increase as more companies look to finance the kind of clean energy and carbon removal projects Watershed has made a focus.

Product: A Climate OS

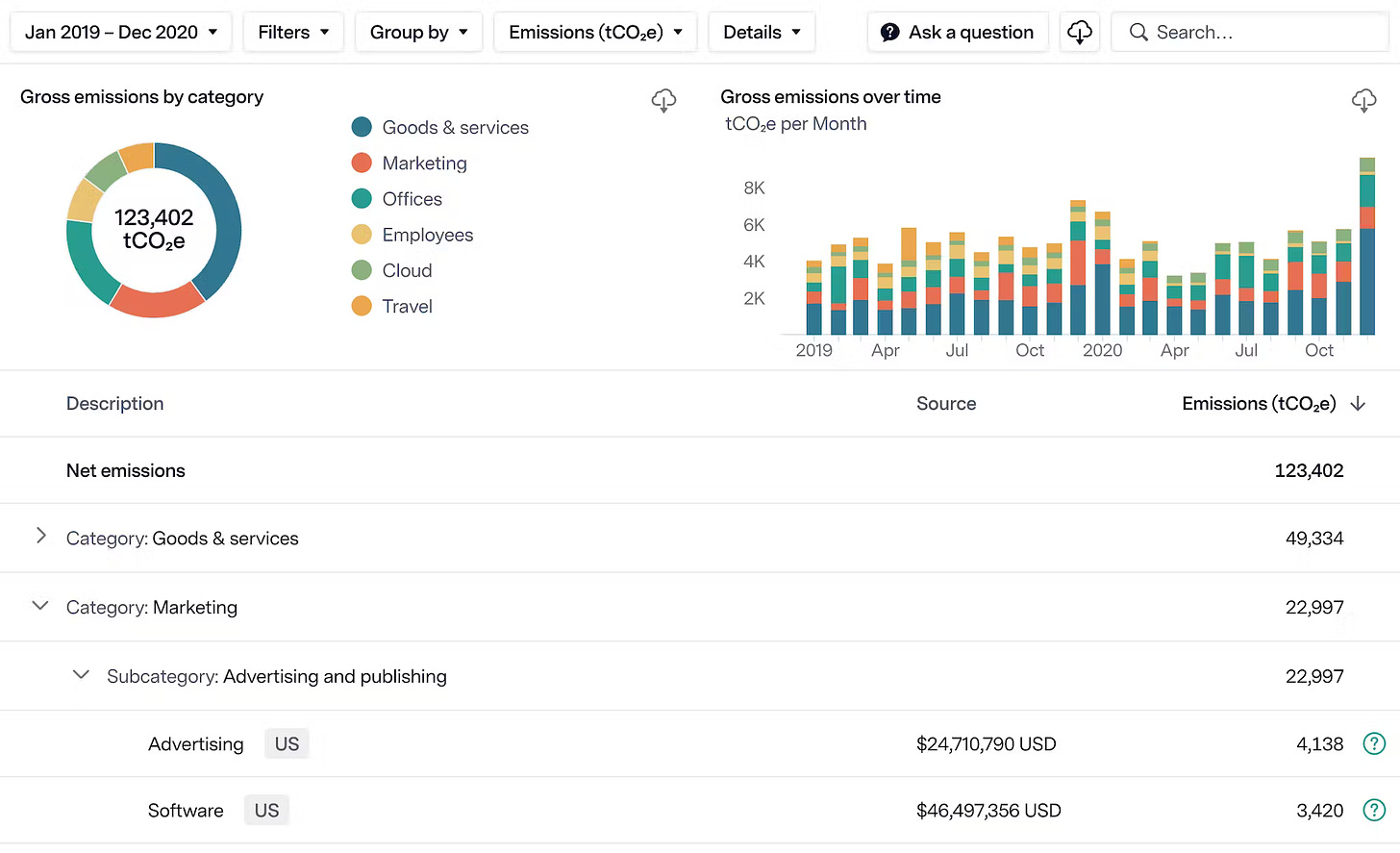

Watershed’s product is best understood by the four problems it solves: measurement, reporting, carbon reduction, and carbon removal.

Measurement is at the center of Watershed’s work. The company has built a powerful “climate engine” that analyzes “every line item” of a business, including the electricity it consumes, the supply chain it leverages, and the materials used to create its products. Clients can generate a footprint in weeks by uploading files, connecting APIs, and adding raw data to Watershed’s system. The swiftness of the process obscures how much complexity the underlying platform has to wrangle. How do you accurately measure the footprint of beauty brands, salad chains, software companies, and health insurers from the same platform?

Since its founding, Watershed has built a sophisticated database of more than 500,000 emissions factors. That means that if you’re a company measuring its footprint from scratch, you likely have some reliable starting points on the platform, whether it’s gauging the footprint of a textile manufacturer, delivery service, or financial provider. For customers that want more granularity, Watershed offers supplier engagement tools that make it easy to collect data from external stakeholders.

As Head of Product Tara Seshan explained, the result is a solution that can help companies understand emissions on an SKU-by-SKU basis. “Everlane has their carbon neutral shoe visualized in Watershed,” she offered as an example. “You can see all of the emissions upstream and downstream in terms of delivering that shoe within the product.”

Watershed has made significant moves in the past year to strengthen its measurement capabilities. In the summer of 2022, the firm announced the appointment of Steve Davis as Head of Climate Science. “It’s very data intensive to measure emissions in a really accurate way,” The former UC Irvine professor explained. “What we are trying to do is be very smart about how we go about it – focusing on the pieces of a company’s activities that we know are going to be the largest sources of emissions, and prioritizing our data collection and methodological innovations around those things.”

Davis is just one of the climate luminaries associated with Watershed. In addition to Al Gore, investors and advisors include Christiana Figueres, ex-UN Climate Change Executive Security; Mark Carney, the former Bank of Canada and Bank of England governor, now engaged as a UN climate action envoy; a pair of erstwhile SEC commissioners; and a smattering of philanthropic and political pioneers. Though none of these notables should be expected to influence Watershed’s climate engine concretely, their backing speaks to its rigor.

Last month, Watershed reported it had acquired VitalMetrics to boost its database further. Founded in 2005, the Santa Barbara-based firm created the Comprehensive Environmental Data Archive, better known as “CEDA.” Unlike many other emissions factor databases, CEDA is updated yearly and covers 95% of global emissions across 148 countries. Though Watershed allows other organizations to use CEDA, it should uniquely benefit from having the founding team aboard, improving its approach. As carbon accounting becomes more competitive, excelling at measurement will be increasingly important.

Reporting has become increasingly essential as companies respond to market and regulatory pressure. Firms must share the state of their business with shareholders and governmental agencies. Watershed does the work to gather relevant data and present it in compliant formats. For example, if a company is based in the UK, Watershed can help ensure its reports adhere to the national Streamlined Energy and Carbon Reporting (SECR) standard.

Once companies understand their footprint, Watershed assists in implementing a reduction plan. That might involve setting a specific goal, like reaching net-zero emissions by a certain date and providing the guidance necessary to progress. Watershed offers in-house climate experts to assist in this process, replacing traditional carbon consulting firms. Already leading companies have committed to significant reductions. For example, Airbnb, Block, and ServiceNow all used Watershed to declare their intent to reach net zero by 2030.

To help companies reduce their emissions, Watershed unveiled an exciting clean energy purchasing program in conjunction with Ever.Green. Using the company’s platform, customers can purchase energy directly from clean power developers. This process has a much higher impact than many other methods of purchasing clean energy, as a developer can use purchase commitments as collateral to secure financing for their project. By engaging in this “Virtual Power Purchase Agreement” (VPPA), customers directly contribute to constructing new facilities that wouldn’t have existed otherwise. This type of transaction has traditionally been out of reach for all but the largest companies, but by bundling them together, Watershed empowers smaller enterprises to participate.

Steve Davis summarized the process. “What we’ve done is to syndicate among a bunch of our customers the output from a single solar farm. Individually, those customers wouldn’t be large enough to warrant that kind of investment – they group together and can have this real impact on the power sector.” Stripe, Samsara, TaskUs, and other customers are now contributing to the construction of a solar plant in Laredo, Texas. The emissions it reduces are equivalent to removing 3,000 cars from the road every year.

Removal is the final piece of the puzzle. Watershed doesn’t just want customers to cut their emissions; it hopes they will also invest in pulling CO2 out of the atmosphere and securing it in long-term storage. Clients can review a range of carbon removal providers from the Watershed dashboard. The innovation on offer is astounding. Here’s a selection of Watershed-approved solutions:

Eion. This “enhanced rock weathering” company grinds up a mineral called olivine and then transports it to farmers, that spread its dust over their fields. As well as acting as an effective fertilizer, olivine helps to absorb and mineralize CO2. Undo, another provider in Watershed’s marketplace leverages a similar approach.

Heirloom. Limestone is one of the world’s great natural carbon sinks but acts on a very long time scale. Heirloom has sped up this process. It conducts a mesmerizing, recursive process of breaking down and regenerating limestone to absorb CO2 much faster. This video is a wonderful introduction.

Charm Industrial. Using a process called “fast pyrolysis,” Charm converts biomass waste like sawdust and corn stalks into bio-oil that it pumps deep into the ground, where it is stored safely. To date, Charm has removed over 6,000 tons of CO2.

Many of Watershed’s providers are offered thanks to a partnership with Frontier. Kicked off by Stripe as a continuation of the climate program Anderson helped launch, Frontier is an “advance market commitment” to purchase $1 billion of permanent carbon removal by 2030. Shopify, Meta, McKinsey, and JP Morgan are among contributing companies. As part of its program, Frontier assesses suppliers and handles removal purchases – Watershed’s clients can now piggyback off this work.

It’s a win-win. Watershed offers its customers impactful, well-diligenced removal providers, while Frontier benefits from additional purchasing volume. Together, the pairing expands access to carbon sequestration’s bleeding edge.

For customers like Misfits Market, a grocery delivery service that reduces food waste, the impact of Watershed’s product suite is powerful. Head of Sustainability Rose Hartley noted that Watershed not only helped Misfits understand its footprint but calculated the improvements the company has made, such as handling delivery in-house. “Watershed is able to say, ‘Here are the avoided emissions of what you’ve saved,’” Hartley explained. “It’s so important for us to be able to talk about that.”

Using Watershed has also assisted Misfits in educating its workforce. The company has held “lunch and learn” sessions for employees that unpack topics like carbon accounting. Given Misfits’ focus on sustainability – 35% of food in the US is wasted, creating a carbon footprint larger than the airline industry – deepening a connection to the sector is powerful. Hartley remarked, “Watershed helps us feel like every job at Misfits is a climate job.”

Model: Sustainable yields

Watershed’s primary source of income is the subscription fee customers pay to use its software. The company declined to share its pricing structure, though looking at competitive products gives a rough benchmark. Persefoni, a carbon accounting platform that focuses on asset managers, charges between $55,000 and $260,000 per year, depending on the size of the customer in question. The highest tier is reserved for businesses earning more than $5 billion in revenue annually. Salesforce’s “Net Zero” suite seems to operate in roughly the same range, reportedly costing between $48,000 and $210,000 per organization per year. Some competitors do offer lower-priced options, but these offerings seem more analogous.

Transactions that occur via the platform provide a secondary revenue stream. When a customer participates in a clean energy purchasing agreement, buys a carbon offset, or purchases removals from a provider like Charm Industrial, Watershed takes a cut. How much exactly?

Again, the company declined to share exact figures, though it suggested its fee was lower than traditional standalone carbon brokers. Assuming Watershed does not benchmark itself against the unscrupulous brokers that make 700% mark-ups (a safe bet), its take rate is likely sub-15% and perhaps lower than 5%.

As mentioned, Watershed’s Series B valued the firm at $1 billion. Without knowing Watershed’s fee structure, it’s difficult to parse that pricing. What multiple did investors implicitly put on the company’s revenue? How does it compare to other fast-growing enterprise software players?

We can, at best, provide a hazy response to such questions. Let’s make a few assumptions:

Watershed serves ~250 customers. The company shared that its customer base number is in the hundreds but didn’t share further details. By our count, Watershed lists 48 unique company logos on its website. With that in mind, we assume the customer number is on the lower end of that implied spectrum.

Watershed has a similar pricing structure to Persefoni. Though Persefoni focuses more on investment firms, we assume similar pricing schemes. Without a clearer sense of customer composition and given the big names Watershed has aboard, we’ll use a fee of $80,000 per customer – north of Persefoni’s lowest tier.

Watershed’s marketplace revenue is minimal. While the platform’s marketplace is extremely impressive and could process large volumes in the future, it seems to be on the newer side for now. Especially given the low take rates it touts, we expect Watershed to earn minimal revenue from this avenue – we’ll exclude it from our estimation.

Using these assumptions, we estimate Watershed’s annual recurring revenue at $20 million. If correct, it would require a 50x revenue multiple to reach the $1 billion benchmark. For context, the median next-twelve-months (NTM) revenue multiple for high-growth SaaS stocks is approximately 10x, though the sector’s strongest businesses command double that.

It’s worth emphasizing that in the absence of better data, this estimation is extremely speculative. Virtually every aspect of the calculation could be spun in the other direction: Watershed could theoretically have 800 customers paying $150,000 yearly, producing an ARR of $120 million. Though we think a ballpark of $15 million to $30 million is much more likely, we don’t have sufficient data to rule out significantly higher figures. It could have conducted an unannounced round of funding at a valuation much higher than $1 billion.

Such calculations may miss the point for vision-based investors like John Doerr and Michael Moritz. Though one does not become a legendary investor without a strong nose for valuation, the best venture capitalists tend to focus on a company’s ceiling, not its floor. Watershed is an example of a business with an extraordinarily high ceiling. It has built a sector-leading position selling an increasingly essential product in an exponentially expanding market. It has constructed a sophisticated platform, hooked the world’s largest businesses, and tied up an investor and advisory base of power players in less than four years. And it is run by a high-performance team used to build massive technological infrastructure at scale. When that constellation comes together, focusing too firmly on multiples may be a mistake.

Competition: Going for the green

In 2020, $63 million of venture funding went to carbon accounting startups. In 2021, the figure rose to $356 million, 5.6x as much. As Michael Moritz remarked, “This is one of these new market areas that’s being propelled by some very powerful fuel.” As well as potentially being a miniature productive bubble, the carbon accounting boom means that Watershed is not short of competitors. From above and below, inside its home city and outside the country, it faces innovative rivals seeking a chunk of the green economy.

Look at Watershed’s customer base today, and you’ll see a carefully manicured selection that spans industries. The presence of BlackRock shows Watershed can serve financial institutions, Walmart stands for commerce and scale, Everlane demonstrates apparel chops, Sweetgreen proves an understanding of foodstuffs, and a string of tech companies reveal Watershed’s comfort serving software businesses. It’s what we might call a “lighthouse approach” – Watershed is studiously picking up brand name players across different sectors, careful not to pen itself in.

Not all companies take this approach. Though the boundaries are hazy, several of Watershed’s fellow insurgents have more firmly specialized.

Take, for example, Persefoni. Founded in 2020, the Tempe-based firm has raised more than $114 million to serve financial firms like TPG and Citigroup. Though Persefoni works with customers outside of this space – including venture-backed businesses like Bumble and Faire – it primarily assists private equity firms, creditors, and banks.

CarbonChain competes for this clientele, albeit from an English HQ. Customers include European banks like Societe Generale, Rabobank, and ING. CarbonChain also looks to be building a specialization in manufacturing and freight. It reportedly offers data on 135,000 ships, giving it strong sea transport measurement abilities. The company recently announced a $10 million Series A led by Union Square Ventures to develop its platform.

Sinai ditches the bankers but shares CarbonChain’s interest in heavy industry. The San Francisco-based firm works with large grain processors like Caramuru and manufacturers like Siemens Energy – traction that has earned it $36 million in funding. Emitwise, a smaller player, seems to focus on the packaging industry with customers like Pregis.

Any time you have competing startups with different beachheads, it raises a question: which is the best approach? What avenue offers the fastest, clearest path to victory? Though Watershed boasts a broad base, no true heavy industry customers are cited on its website. The closest it gets is Flexport and Boom Supersonic. Will its inexperience serving complex, unsexy industrial businesses with complex supply chains count against it in the long run?

Watershed has an extremely capable team and the connections to attack almost any industry. That said, it doesn’t seem trivial to build for these heavy-duty sectors. If Watershed wants to win the entire market opportunity, it may be important to demonstrate its ability to crack these tougher customers over the next year or so.

Geography may also prove a powerful advantage. Europe leads the US in understanding and addressing the climate crisis. It’s unsurprising that so many of the space’s startups originate from the region.

France, in particular, is a popular starting point, home to Sweep, Greenly, and Carbon Maps. Sweep has raised the most capital to date, pulling in roughly $100 million from Coatue and Balderton Capital. Customers include Ubisoft, Prose, and Withings. Other European players include Plan A, based in Berlin, and Normative, headquartered in Stockholm.

Watershed is awake to the European opportunity. The firm plans to “invest deeply” in the region, hiring former Stripe operator Ellen Moeller to lead a local team. Twenty percent of Watershed’s revenue came from Europe before Moeller’s 2022 appointment – one would expect it has meaningfully increased given Watershed’s investment in winning the geography.

As much as Watershed will want to remain abreast of its fellow startups, it will be more concerned by the growing interest of enterprise giants.

Salesforce, Microsoft, and IBM all offer carbon accounting solutions. Of these, Salesforce appears the most complete – in addition to traditional measurement tooling, the CRM-maker supports a “Net Zero Marketplace,” through which customers can purchase carbon credits. Of course, from a high level, that’s a very similar structure to Watershed’s product. Consulting firm McKinsey is even getting in on the act, with its Sustainability practice pushing out a software platform named “Catalyst Zero.”

Watershed will worry most about Microsoft and Salesforce. The former has quite a track record of kneecapping promising enterprise software businesses by releasing a homegrown solution; Watershed will not want to get Slack-ed. Salesforce has built a similarly capacious software suite, though much of it has been achieved through acquisitions. There’s also good reason to think that having carbon accounting as part of a broader enterprise suite could prove beneficial. To measure a business’s footprint, a user must upload all kinds of company data from spreadsheets to databases – having all these systems easily sync up could provide a smoother experience.

Ultimately, Watershed should remain vigilant but operate without fear. Building an accurate carbon accounting product is much more complex – with its varied data sources and esoteric methodologies – than emulating a communications application like Slack. While the activity level in the space means some consolidation is inevitable, Watershed will reasonably believe it has the ingredients to be a strong, standalone winner.

“Those who have the privilege to know have the duty to act,” Albert Einstein said. Watershed is a software platform that empowers both: knowing and acting. By giving companies a clearer picture of their emissions, Watershed guides them toward reducing them and investing in carbon removal. It is a simple proposition in its essence, but one that takes formidable talent to undertake effectively. Watershed’s strength is that it understands the scale of the problem and the language, the product, most likely to drive change among its customer base. It is a pragmatist with a dreamer’s spirit.

The Generalist’s work is provided for informational purposes only and should not be construed as legal, business, investment, or tax advice. You should always do your own research and consult advisors on these subjects. Our work may feature entities in which Generalist Capital, LLC or the author has invested.