On Productive Bubbles

Not all speculation is created equal. How will we remember the AI, venture, crypto, and climate bubbles of the early 21st century?

Brought to you by Mercury

Secure banking, the startup way.

Every founder’s top priority right now? Keeping their cash safe. But that doesn’t mean they have to settle for a bank with clunky features and complicated services. Mercury offers secure banking* engineered precisely for the pace and creativity of startups — all through an intuitive product experience that innovates alongside you.

Via Mercury’s partner banks and their sweep networks, customers can access up to $5M in FDIC insurance — 20x the per bank limit. These sweep networks protect your deposits by spreading them across multiple banks, limiting the risk of any single point of failure — and giving you peace of mind.

You want to spend time actually building your startup — not worrying if your cash is safe, waiting in line, or navigating a confusing website. Plus, with Mercury, it’s simple to get started. Applying takes minutes and many customers are approved and onboarded in less than two hours.

Join more than 100,000 startups that trust Mercury for banking.

*Mercury is a financial technology company, not a bank. Banking services provided by Choice Financial Group and Evolve Bank & Trust®; Members FDIC.

Actionable insights

If you only have a few minutes to spare, here’s what investors, operators, and founders should know about “productive bubbles.”

Beneficial bubbles. Some speculation may be worth the pain. According to economist and investor Bill Janeway, “productive bubbles” have helped create some of our most important infrastructure, from railroads to the internet. While plenty of waste occurs during these frenzies, they improve life for successive generations.

Uncertain applications. Part of the reason even productive bubbles are wasteful is that it’s incredibly difficult to find “killer applications” for novel technology. For example, one early use case for the telephone was listening to music; meanwhile, radios only embraced broadcast after World War I. It may take decades for innovation to find its ideal implementation.

The limits of foresight. Janeway’s theory demonstrates that even when an investor is correct about the world-changing potential of a new technology, they can still lose their shirt. Plenty of investors that shrewdly foresaw the impact of the internet, for example, were still decimated by the dotcom bubble’s bursting.

Useful remnants. We are emerging from an “everything bubble,” that touched public markets, venture capital, crypto, and beyond. A new AI froth is forming rapidly. What, if anything, are the productive remnants of our past and present immoderacies?

Climate next? Though Elon Musk and Tesla helped create a green tech bubble, galvanizing the creation of new electric vehicles, a broader climate bubble could be on the horizon. Given the existential stakes, we might all benefit from a period of frenzied over-investment in the sector.

Sometimes, the economy really does hang by a thread.

On May 3, 1893, the National Cordage Company – a maker of twine and rope – collapsed, sparking the meltdown of the American economy and puncturing the era’s biggest bubble: railroads.

In our age of skimming, soundless electric vehicles, darting scooters, and slaloming segways, the railroad sounds like a dusty inheritance: a grime-dappled silver platter, a sunworn sofa set. Not so in the 19th century. “The one moral, the one remedy for every evil, social, political, financial, and industrial, the one immediate vital need of the entire Republic, is the Pacific Railroad,” the Rocky Mountain News raved in 1866. This was the technology of the future, a galloping machine that ate fire, breathed vapor, and folded the American map until its cities touched.

What should a financier do when confronted by such ingenuity, such startling modernity? Invest, of course. Don’t concern yourself with petty things like prices or projections; overlook rhapsodic marketing and overlapping lines; put your money into the designs of the Philadelphia and Reading Rail Road (P&R), Northern Pacific, Union Pacific, and dozens of other scrabbling tracklayers. These businesses were the startups and unicorns of their day: fast-growth “sure bets,” reaching toward the horizon. Indeed, in 1871, P&R became by some measures the most valuable company in the world, valued at $170 million, north of $3 billion today.

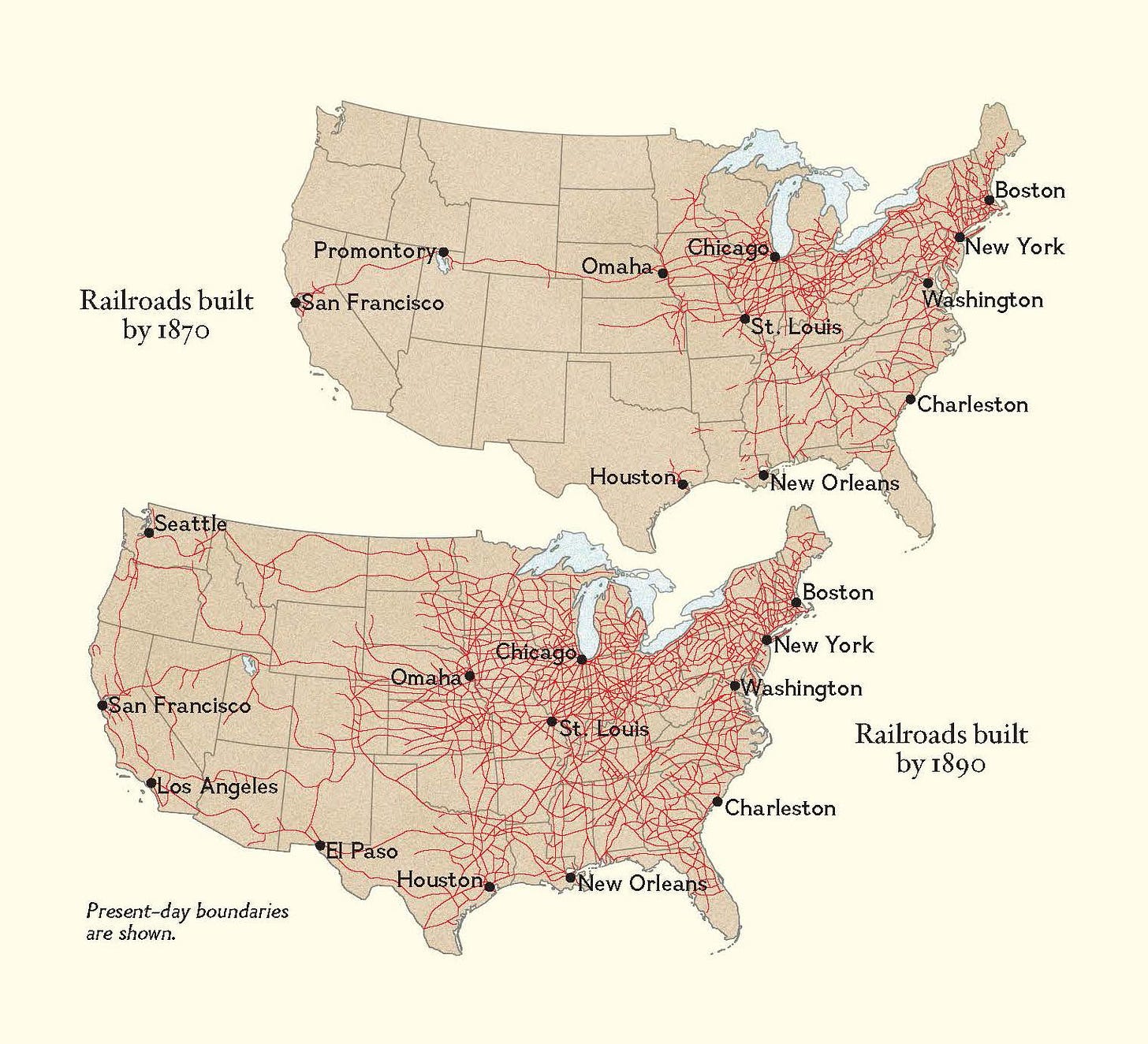

Flush with cash, powered by low-cost immigrant labor, boosted by government support, and unmolested by oversight, “railroad fever” defined much of the 19th century. An “orgy” of construction saw miles of track increase from 45,000 in 1871 to 220,000 by 1900, a nearly five-fold increase. In the 1880s, railroad firms made up an astonishing 80% of the New York Stock Exchange’s listings and delivered twice the government’s revenue.

And then, it all came crashing down. Panic over gold reserves and the demise of the P&R fretted investors, but the sudden collapse of National Cordage marked the true beginning of the “Panic of 1893.” In the following months, thousands of railroad workers lost their jobs as Northern Pacific and Union Pacific followed P&R into bankruptcy. By the next year, 25% of railroad businesses had made the same bleak journey. A broader economic depression lasted years.

Time reveals truths obscured by the present. While many suffered during that spell – losing work and watching as wealth evaporated – the railroad mania of the 1800s merited the damage it caused. Though wild and unhinged, speculation attracted massive pools of capital for a monumental infrastructure project. Companies failed, and investors lost their money, but, for the first time, tracks knitted American industry together. This sparked new efficiencies and spawned radical industries, including mail-order retailers like Sears.

It was a perfect example of a “productive bubble,” a term coined by economist and investor Bill Janeway. Unlike pointless fits of speculation such as the Dutch tulip craze of the 1630s, “productive bubbles” leave society better off, undergirded by new technological infrastructure, even as investors lose their shirts.

No imagination is needed to understand how Janeway’s concept fits into our current era. We have been living between bubbles of different sizes and maturations for much of the last decade and a half, riding the froth and foam of venture capital, crypto, meme stocks, SPACs, and, presently, AI. Some have burst or are in the process of doing so, while others are still inflating, amassing hot air.

Which, if any, of our speculations will prove most productive? Which frenzy might future generations appreciate?

Productive bubbles

Before looking at the ruptures of our contemporary era, it’s worth fully defining Janeway’s concept.

Economic history is littered with bubbles. Indeed, a bit of froth is liable to form wherever a market emerges. Over the centuries, gimlet-eyed speculators have salivated over gold, silver, uranium, real estate, equities, digital tokens, flowers, and beyond.

Typically, these events are viewed with a mixture of disdain and disgust. How could so many be so foolish for so long? What derangement excuses such total, brainless waste? In this rendering, virtually everyone loses; there are no heroes. The world is awash with charlatans, opportunists, and those feeble-minded enough to believe both.

Sometimes, this is the whole story. Sometimes, a bubble offers nothing more than the nausea of a sharp rise and stomach-churning drop. The tulip craze of the 1630s, the Beanie Baby mayhem of the 1990s, and most of the ICO psychosis of 2017 fit this bill. These speculations hoovered up capital and delivered next to nothing of value, cleaning out investors in the process.

As Bill Janeway chronicles in his prodigiously named book, Doing Capitalism in the Innovation Economy: Reconfiguring the Three-Player Game between Markets, Speculators and the State, not all bubbles fit this profile. The annals of financial exuberance include many events in which hysteria produces something profoundly valuable. Speculation has sponsored critical infrastructure, created only thanks to “productive bubbles” that supply the capital needed to bring them to fruition. A selection of great American bubbles:

Telegraph fever (1840s-1850s). Samuel Morse’s new communication device sparked widespread excitement and investment. The number of telegraph miles rose ten-fold between 1846 and 1852 – never mind that many were redundant or effectively unusable. Though most telegraph firms failed, America benefited from new informational infrastructure and applications – like sending money by wire – built atop it.

The electrification boom (1920s). Favorable economic conditions, governmental intervention, and financial speculation expanded the prevalence of electricity in America. At the start of the decade, 35% of households had electricity; within nine years, it had nearly doubled to 68%. The crash of 1929 pummeled the economy, including utility providers, but America’s electrical availability had been decisively enhanced.

Internet bubble (1990s). During the 1990s, more than $30 billion was spent building 90 million miles of fiber-optic cable. Meanwhile, a generation of “dotcom” businesses snaffled capital and reached wild valuations. In 2000, the bubble burst, resulting in the culling of tech companies and infrastructure providers. By some estimates, just 5% of fiber-optic capacity was used in 2001. Of course, the decades since have demonstrated the value and importance of the internet and the infrastructure that powers it.

Ours is a history littered with productive economic confusion. Though these examples hopefully bring Janeway’s core concept into closer view, questions nevertheless remain. Among them:

How do you identify a productive bubble?

Can innovation occur without mass speculation?

How do companies forged in a bubble fare?

Firstly, how do you identify a “productive bubble?” Time tends to reveal whether our deliriums have been well-directed. However, a more concrete assessment method is to see if speculation centers around a “general purpose technology” or GPT (not that kind). As defined by the economist Timothy Bresnehan, a GPT is “widely used, capable of ongoing technical improvement, and enables innovation in application sectors.” Bresnehan adds that the GPT and application positively amplify one another; improvements to the GPT empower new applications to form, and new applications demonstrate how the GPT can be better developed.

Janeway cites steam power, electricity, and the internet as exemplar GPTs, relied upon by “application sectors” like railroads, manufacturing, smartphones, and search. Bubbles that facilitate the exploration and expansion of GPTs and associated applications can be productive.

Secondly, could this infrastructure have been built without all the speculation? It’s a reasonable question. Even when productive, bubbles are messy affairs that leave many businesses bankrupt. As Janeway writes, “It took the wastage of a bubble to fund the exploration that would yield Amazon and eBay and Google.” Despite its profligacy, however, financial speculation can gather the large sums of capital needed to build new networks. Janeway suggests that only the state can mobilize equivalent resources.

The state and speculator’s involvement in such activity is “decoupled from the rational calculation of gain from [a] project over its economic life.” The government does not build a highway system because it seeks a financial return; it does so for the sake of its citizenry. For example, in France, the government devised and implemented the railway system – the result is a much more orderly network without the overlapping redundancies that the American capitalist iteration involved.

Equally, the financier that YOLO’d into Union Pacific rationally could not have expected the project’s cash flows to repay his investment. Indeed, the more novel the innovation, the more unknowable its realistic cashflows. Rather, the financier was driven by a desire to “[ride] the psychology of the market,” making money as the asset bubble inflates.

Innovations do occur beyond state programs and financial frenzies, of course. Research and development (R&D) centers like Bell Labs and Xerox Parc have a rich history of invention. Janeway notes that none of the networks that emerged in the wake of the railroad excesses required as much capital, with less money needed to roll out local telephone networks. Though not the only way, bubbles do amass considerable capital around specific assets – often at scales not possible by other means.

Finally, how do companies founded in bubbles fare? Though not a comprehensive historical study, one research paper suggests that bubbles may produce more highly valued businesses, albeit at a cost. “Investment cycles and startup innovation,” written by Ramana Nanda and Matthew Rhodes-Kropf of Harvard Business School and the National Bureau of Economic Research, finds that startups that first raise capital in a frothy environment are more likely to file for bankruptcy, while those that eventually go public do so at greater valuations, with more and better-cited patents. Given the power law dynamic of venture capital, that skew can prove attractive. After all, history will not remember John Doerr’s dotcom misses, only that he backed both Google and Amazon.

The folly of predictions

It takes humans time to learn how to best implement our most disruptive inventions. One early application for the telephone, for example, was as a form of entertainment. Users could listen to a live performance of a concert or show with a device – long before radio broadcasting became available, let alone modern streaming. Today, a traditional telephone is primarily used as a method of communication, and listening to music with it is considered a modern form of torture, restricted to waiting on hold.

Conversely, as Janeway outlines, the radio only started to be used as a broadcast tool after the First World War. Before that point, it was almost exclusively leveraged as a method of communication. Juxtaposed, it becomes clear that early interpreters of telephony and radio got their use cases precisely backward.

History is full of such examples. Reading early assessments of the internet is a source of intrigue and humor now. In a 1995 Newsweek piece, systems engineer Clifford Stoll shared his view of the network:

Visionaries see a future of telecommuting workers, interactive libraries and multimedia classrooms. They speak of electronic town meetings and virtual communities. Commerce and business will shift from offices and malls to networks and modems. And the freedom of digital networks will make government more democratic.

Baloney. Do our computer pundits lack all common sense? The truth is no online database will replace your daily newspaper, no CD-ROM can take the place of a competent teacher and no computer network will change the way government works.

It is easy to read Stoll’s words now and laugh, but his was not a lone voice. The same year Stoll’s piece was published, David Letterman interviewed Bill Gates, providing an analysis of the internet that reflected mainstream opinion. In discussing the novel ability to listen to a baseball game online for the first time, Letterman quips, “Does radio ring a bell?”

There is an interesting meditation when considering innovation and the unknown. Which is to ask: what kind of wrong do I want to be? Would I prefer to be sneered at by contemporaries as I foretell great wonders or laughed at by successive generations for my skepticism?

These are not rhetorical questions. “Pessimists sound smart, optimists make money,” goes one tech aphorism. Though it gets at the heart of the mind-boggling returns that may occur from taking a correct contrarian position in the sector, it has always struck me as fundamentally misleading. Pessimists sound shortsighted when disproven – as our review of internet skeptics shows. Even in the moment, a pessimist often comes off as little more than a modern Luddite, railing against inevitable progress, missing the magic of invention.

Meanwhile, even when an optimist is proven right, they may not make money. The history of productive bubbles is one of speculators correctly identifying a transformative technology – and getting wrecked in the process.

Congratulations, you correctly predicted the revelation of electricity! Black Thursday will ravage you just the same. Felicitations for foreseeing the potential of e-commerce – but why did you pick Pets.com? When assessing unproven technologies, there are a near-infinite number of ways to miscalculate, underestimate, or oversell.

With that framing, we analyze four bubbles past, present, and future: “unicorn,” crypto, AI, and climate.

The unicorn bubble

In the second edition of Doing Capitalism, published in 2018, Janeway foresaw the detonation of the “unicorn bubble,” the inflation of venture-backed startups. I had the chance to speak with Janeway about his work earlier this week. With the benefit of five additional years, does he view the unicorn bubble as productive?

The Cambridge academic is skeptical of some of the business models that emerged. “It’s definitely produced some services that could never have been sustainably delivered other than in a bubble and many seem likely to go away,” he said. “I think kids are going to have to learn that if you want a pizza, you may have to wait for an hour and a half.” In broad strokes, Janeway suggested on-demand businesses like scooter company Bird and food delivery platform DoorDash may struggle in the coming years, unable to achieve the positive cashflow he calls the “key to corporate happiness.”

Though Janeway seems broadly dubious of the benefits of venture’s immoderacy, he suggests some positives. Doing Capitalism makes interesting reference to enterprise software investments. Though perhaps an example of damning with faint praise, Janeway outlines how that sector has morphed from one that produced “sustainably successful new businesses” into outsourced R&D for industry giants. While Microsoft might have allocated internal resources to spinning up new workplace tools in the past, they can now purchase the best-performing startups or ape their offerings. In a minor key, this may make venture’s funding of the sector partially productive.

Is that all we’ve been left with? From our current vantage, there are several improvements this stretch of venture frenzy appears to have given us:

A renovated financial system. Approximately $1.2 trillion was deployed in fintech between 2010 and 2022. That investment resulted in a reinvigorated and modernized financial system that operates more efficiently, better serves customers, and expands access. This includes companies like Stripe, Plaid, Nubank, and Mercury. The old guard has been forced to catch up, with players like Goldman Sachs embracing technology.

Ubiquitous smartphones. An increase in the number and power of mobile applications helped mainstream smartphones. Companies like Uber that uniquely leveraged the new device’s capabilities were particularly important. We are still in the early innings of understanding what it means for billions of people to have a powerful computer, endless web, remarkable camera, and infinite map in their pocket at all times.

Digitization of laggard industries. As low-hanging markets saturated, venture dollars chased companies attacking laggard sectors, including healthcare, logistics, heavy industry, defense, education, and beyond. Examples include companies like One Medical, Oscar, Flexport, Anduril, and ClassDojo.

Internet-first businesses became increasingly viable. It would have been much harder to run The Generalist a decade ago. At various points, we’ve relied on digital payment processors (Stripe), a modern publishing platform (Substack), a simple but powerful website builder (Webflow), an online accounting product (Bench), and dozens of other platforms. VCs financed numerous digital tools to empower internet-native SMBs.

Near-universal content availability. Venture capital funded a wave of businesses that create, organize, and deliver digital content. Examples include YouTube, Spotify, Reddit, Twitter, Substack, and Twitch. While not all digital content is especially salubrious, these platforms have provided considerable entertainment and, in many cases, huge educational value. It is increasingly possible to learn anything from anywhere.

Digital coordination of under-utilized assets. Companies like Airbnb demonstrated how technology could improve asset utilization, allowing people to make money from renting their spare rooms. While leading “sharing economy” companies have matured beyond such quaint origins, they pioneered a way of bootstrapping networks without owned assets and unlocked value.

We could find perhaps hundreds of other arguably beneficial outcomes of venture investment. Only time will tell which are truly productive.

The crypto bubble

Despite greatly admiring Janeway’s theory and perspective, we partially diverge when it comes to crypto. “I certainly do not think crypto represents a productive bubble,” Janeway remarked in our conversation. “I think it’s something between a distraction and a waste of time on the one hand, and an environment that invites multiple kinds of speculators.”

I have gotten plenty wrong when it comes to crypto and am very alive to the fact that the sector’s attention, controversy, capital, and tribalism make it particularly tricky to analyze. (Interestingly, this has been true of many disruptive technologies.)

Like Janeway, I believe crypto has a structural and cultural problem regarding its obsession with gambling and speculation. The level of fraud and celebration of pointless betting has created an environment that often closely adheres to an unregulated casino. I’ve suggested that crypto is at a “turning point” within Carlotta Perez’s adoption cycle framework. If it wants to enter a prolonged, meaningful “deployment phase,” it must address these issues and find clearer utility.

However, despite those misgivings, I remain optimistic about its potential. Though we may need decades to determine whether the tens of billions invested in the sector become productive, fundamentally, I believe the separation of money from state, advent of trustless systems, introduction of self-sovereign identity, and construction of “internet-native” property and entities could prove powerful. Below are early, experimental crypto use cases that show promise:

Stablecoins. Americans underestimate how attractive dollars are outside of the country. If given a choice, much of the world would prefer to earn and keep their savings in USD, a stable currency. Local regulations and punitive rates typically prevent that possibility. Stablecoins offer a synthetic dollar alternative with applications for individuals and businesses globally. Of course, the difficulty is scaling an actually stable cryptocurrency – if achieved reliably, at scale, this could have a profound impact. We will see many companies explore this space in the next few years.

Digital ownership rights. Right now, this is associated strictly with NFTs, an acronym that produces such anger in many that it thwarts further discussion. Much of the NFT craze of 2021 will indeed prove an extraordinary waste. However, the core premise of a data structure that offers digital provenance and ownership could prove profound. So far, speculation has focused on narrow, superficial use cases and has failed to advance the boundaries of the technology. Nevertheless, it introduced the concept and familiarized many with it. In time, successive generations may push forward and find greater utility for these ideas in media, financial assets, identity, or something beyond our present imagination.

Digital entities. Though perhaps not as polarizing as NFTs, DAOs evoke a similarly frustrated response from many crypto observers. Many of the much-hyped DAOs of the last cycle have proven to be little more than group chats with well-stocked bank balances. Once again, though, if you look past this initial instantiation, you can see the contours of something interesting: internet-native organizational structures and shareholders. Perhaps nothing will come of this, but I’m excited to see how entrepreneurs take the lessons of DAO-mania and use them to form more pragmatic, productive entities.

Proof of physical work. Our analysis of Helium argued that the “proof of physical work” (PoPW) is notable for pioneering the use of crypto incentives to construct new infrastructure. While its usage was very low at the time, the mechanism by which an IoT network had been created was, and remains, fascinating. Since our piece, Helium has launched a wireless network (still small), and similar PoPW projects like Hivemapper have elaborated on the core mechanism. The ability to fundraise, implement, and orchestrate new citizen-owned physical networks could be important.

Blockspace. In an interview conducted last year, Chris Dixon outlined why blockspace would prove the “best product” of the decade. The a16z crypto GP argued that on-chain capacity would become increasingly important as crypto grows in popularity. Dixon draws a parallel to the over-investment of bandwidth in the 1990s, which later proved essential for scaling the internet. If crypto does take off as Dixon and others expect, the bubble formed around Layer 1s and Layer 2s will have been valuable.

I share these knowing there is a greater chance of being wrong than right. All are speculative; none currently represent an obvious “killer application,” like the mail order catalogs for the railroad, communication for the telephone, or broadcast and the radio.

We also shouldn’t expect them to just yet. Satoshi’s whitepaper might be fifteen years old, but Ethereum’s was less than a decade ago. The vast majority of investment in the sector occurred as recently as 2021. (Much of which will likely end up being a waste.)

Janeway’s research shows that it can take decades for a technology to find its ideal implementation and then reach mass deployment. Antonio Meucci built the first basic telephone in 1849 – it took until 1914 for there to be 1 phone per 10 households and another 31 years to double its ubiquity. In 1965, Lawrence Roberts successfully made two computers “talk.” Only in the 1990s did it become a mainstream product, and, as mentioned, it was still viewed skeptically by many. Just as we now look back on the low fiber-optic cable usage of 2001 with something of a smirk, so might we one day survey the desolation of today’s blockchains and applications.

Given Janeway’s deep study of bubbles, it is unsurprising that he does not entirely write off crypto’s theoretical uses. “I am keenly aware of the potential for it to be applied in a way quite orthogonal to what it was founded to do.” In particular, Janeway cited the interesting research national governments are conducting into Central Bank Digital Currencies. Perhaps crypto’s dominant use will not be as an anarchic, freewheeling technology but as an extension of the state.

The AI bubble

Over the past year, venture enthusiasm shifted from crypto to artificial intelligence, directed by a series of astonishing generative AI demonstrations and products, not least ChatGPT. The result is a new asset bubble. While venture activity and valuations have dropped meaningfully across other sectors, AI companies are raising rapidly and at elevated valuations. Pitchbook Data shows that the average pre-money valuation for generative AI companies spiked from roughly $10 million between 2017 and 2020 to $40 million in 2021 and 2022 and up to $90 million this year. Foundational model companies like Anthropic and Adept have pulled hundreds of millions in funding at billion-dollar-plus prices.

How will this all turn out? There will almost certainly be big winners among investors but plenty more losers. Though it is extremely early days, there are aspects of this hype that look productive:

Foundational models. Companies like OpenAI, Google, Anthropic, and Adept are investing in creating large language models (LLMs). These are extraordinary reasoning algorithms capable of generating words, images, code, arguments, and more. We already see many of these innovations applied across industries, including finance, healthcare, defense, logistics, and beyond. New treatments, pharmaceuticals, cyberweapons, fraud prevention systems, and enterprise tools will rely on these new intelligences.

Modern labs. From a conceptual standpoint, many of today’s leading AI companies operate as quasi-laboratories. Though there is a commercial motivation, there’s also considerable effort dedicated to advancing the field and experimenting on the fringes. In this respect, the movement reproduces early tech labs like those at Bell and Xerox. As those examples of “scenius” show, adequately resourcing leading theoretical and practical talent can yield remarkable results.

Detection and defense. As models become more powerful, I suspect we will see investment coalesce around AI detection and security. Humans will need ways to determine AI-generated text, voice, and images, and every enterprise and government will require protection methods.

Computing resources. AI requires huge amounts of computing power. To meet rising demand, we’ll see companies emerge that optimize and add to existing resources. As with fiber-optic cable and blockspace, this could prove essential as the sector grows.

This isn’t to suggest that the AI will be strictly good. One popular narrative in tech is that AI hype is justified relative to crypto. Finally, a real technology, the advancer of this position exhales.

Such a stance makes sense: after crypto’s bonanza of monkey JPEGs, clunky consumer applications, and rampant fraud, AI feels like a purveyor of effortless, unbelievable magic. Over time, however, I suspect this comparison will cease to be meaningful. In addition to crypto hopefully finding greater utility, we will come to comprehend better the risks AI introduces – by which point it may be too late. In pursuit of competitive advantages, companies are releasing mind-boggling intelligences with few qualms or protections.

Advanced reasoning machines, voice clones, synthetic likenesses, artificial romantic relationships, automated war machines – what could go wrong?

Denizens of the tech sector are extremely gifted at seeing and building the future. But we do not have the best track record of predicting or protecting against damaging second, third, and fourth-order effects. One of the dominant tech stories of the last decade was a lament about social media’s societal impact and how blindly the industry financed networks that have, at least in significant part, undermined base-level truth and cultural harmony.

Perhaps it is too much to expect one industry to both create the future and regulate it. In an ideal world, the government could step in, set rules, and guide development. The American state’s lethargic response to crypto and its legislators’ well-demonstrated technological ineptitude suggest it is not up to the task. As technological progress accelerates, the mishmash between the two sectors will only become more pronounced; a race between a tortoise and a spitfire.

All of which is to say that the current AI boom is spectacular and looks set to radically improve our world, elevate our health, create significant art, and improve productivity. But a dark, frightening ribbon runs through it.

The climate bubble

We can now turn our attention to climate. When surveying recent bubbles, one example of productivity stands out to Janeway. “The obvious one is Tesla and electric vehicles and the acceleration of green technologies.” Though Janeway thinks of Musk as a kind of “P.T. Barnum, a Trump-like figure,” he notes that the Tesla CEO “mobilized resources to clearly accelerate” the adoption of electric vehicles (EVs), galvanizing traditional automobile companies around the world to follow suit.

Although Musk’s business is based in the U.S., Janeway argues that Tesla’s success has been “substantially overshadowed by what’s going on in China.” In 2009, Beijing began heavily subsidizing EV development, pushing $29 billion into the sector by 2022. The result is that more than 50% of EV sales are now in China; Tesla’s Shanghai Gigafactory is purportedly its most productive. While China’s increasing grip over the EV supply chain, including batteries, could prove problematic for America, it has obvious environmental benefits.

Though we can be grateful for the capital Musk has attracted to the sector, we should hope another, broader climate bubble is in the offing. Legendary investors like John Doerr and Chris Sacca have touted the sector’s potential for some time. It would benefit the broader world if more investors started sharing their perspective and deployed capital to solve an existential problem. Already, there are many promising explorations:

EVs and infrastructure. The EV story is far from finished. While China may be increasingly shifting away from petrol-powered cars, many other countries are early in this transition. In India, for example, just 2% of new car purchases are electric, though projects suggest this will hit 30% by 2030. New infrastructure and supply chains, including charging stations, will need to be built for this to happen. Beyond cars, there’s also work to be done electrifying other vehicles. Companies like Heart Aerospace are building fully-electric passenger planes.

Synthetic biology. Our food system is a significant emissions contributor. That has compelled biotech startups to experiment with synthetic proteins, including beef, chicken, eggs, and seafood. Bluefin tuna (Finless Foods), shrimp dumplings (Shiok Meats), and even wooly mammoth meatballs (Vow) are being produced in laboratories. Beyond food, promising experiments are occurring around creating synthetic palm oil (c16 Biosciences), a driver of deforestation.

Nuclear energy. Lux Capital co-founder Josh Wolfe noted that the environmental movement has often been antagonistic toward nuclear power. That is beginning to change, aided by investment in companies like TerraPower and General Fusion. Venture capital funding for the sector peaked in 2021 at $3.4 billion, with hopefully more to come.

Climate as a corporate function. Over the past decade, much of the climate narrative has been that individuals must take responsibility for their waste and emissions. While raising awareness is worthwhile, replacing plastic straws with paper ones will do little to stop the world’s demise. More than individuals, it’s essential that companies take responsibility – just 100 enterprises are responsible for 71% of emissions. Startups like Watershed help businesses like Walmart and BlackRock manage their footprint, giving those with the greatest leverage the tools to do better.

Among potential bubbles, few look quite as likely to be worth the whiplash.

The great writer William Faulkner, the descendant of a rail line owner, said, “History is not was, it is.” The past finds its way into the present, reasserting old patterns, reproducing familiar motions. Throughout economic history, humans have reliably, repeatedly pursued the same folly: discovering an asset or innovation, over-capitalizing it, and finally, driving it to detonate. It is a cycle of extraordinary waste and massive damage, and yet, as Janeway shows, we are often better for it. As we survey the wreckage of our latest speculations – and sprint toward new ones – there’s good reason to believe it may prove productive.

The Generalist’s work is provided for informational purposes only and should not be construed as legal, business, investment, or tax advice. You should always do your own research and consult advisors on these subjects. Our work may feature entities in which Generalist Capital, LLC or the author has invested.